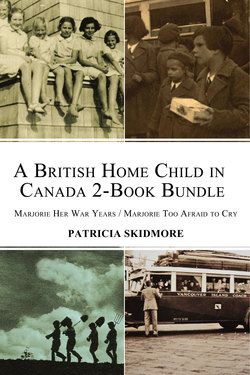

Читать книгу A British Home Child in Canada 2-Book Bundle - Patricia Skidmore - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Seven

ОглавлениеOff to London

Marjorie’s world is falling down,

Falling down, falling down,

Marjorie’s world is falling down,

But no one cares.

September 8, 1937

Marjorie quickly ran a brush through her short, straight brown hair. They had orders to make haste and not to bring anything with them. It was all so puzzling, but still it was exciting. She bent over to put on her shoes. The morning’s oatmeal felt heavy on her stomach. A worried feeling ran alongside her excitement. Adults who talked in a high hurried voice like the one Nurse used this morning were normally to be mistrusted. However, she was going on an adventure! No school today!

“I am so excited. I wonder where we are going.” Marjorie exclaimed.

“Me too. And anywhere but school and the kitchen will be good,” a girl answered from across the locker room.

“I feel special. This is going to be a great day,” a third girl piped in.

“Girls!” Nurse interrupted their happy chatter. “Put on your winter coats and your tams.” This was odd too, because it was such a lovely warm September day, but they were well-trained children and rarely challenged orders now.

Nurse had approached the three girls just after breakfast and pulled them aside before they could get their coats and books and form the usual lineup for school. Olive would be waiting for Marjorie, but Nurse kept them shut away in a little office. Marjorie did not know what she did wrong. She worried about having to walk with a different partner and being late for day school. She trembled at the thought of being sent to the headmaster. It was generally not good news if the day began with anything out of the ordinary. When the Nurse came back the anxiety in the little room couldn’t be contained. She told them not to fret since the school had already been informed of their absence. She clapped her hands and told them that today they were going on an exciting journey.

“Who wants to go on an adventure?” she asked. And naturally there was a chorus of “I do! I do! I do!” from the three excited girls, who had been standing patiently to hear what they had done wrong and what their punishment might be. They looked at each other and smiled their relief to one another. Nurse told them to not tell the others since they might feel bad because they were not invited to come with them. She bent down and whispered, “Okay, girls, this can be our little secret!” The girls nodded and quickly scampered off when Nurse said they had just ten minutes to get ready.

A twitter of excitement followed them down the hall. They did not have to worry about letting their secret out since the home was almost deserted. Most of the other children had already left for school and the younger ones were in the babies’ room. That left just a handful of the older children at the home at this time of the morning and they were busy doing their chores. They ran up the centre stairs to the girls’ locker room, chatting happily, without a care in the world.

The girls were ready in record time. The thought of doing something different was so exciting, and besides, they were the chosen ones that day. Marjorie quickly buttoned her coat, hoping there was time to slip into the kitchen to tell Joyce about her adventure. Joyce was good at keeping secrets, and she would tell her that she would come immediately to the kitchen when they returned instead of at their usual meeting place after day school. Marjorie smiled to herself; she loved their private spot down at the bottom of the field. Joyce would run up and laugh as she pulled the hidden treats out of her pocket. Sometimes Marjorie shared the treats with her best friend, Olive, but more often than not, she just popped the treats into her mouth, savouring the yummy taste.

Olive’s friendship had become very important to Marjorie. She was there to whisper to at night and this was a great comfort as Joyce and Audrey’s cots were too far away. It was difficult to make friends at the home because so many of the girls kept leaving. Marjorie felt special having such a good friend plus a big sister to look out for her. Joyce was the best big sister anyone could ask for. As she put on her tam, she thought that it was not so bad there really — at least they had each other. Not all of the kids were as lucky as she was; some of the girls had no family at the home, not even a brother.

Marjorie was ready first. This would be her only chance to run to the kitchen. As she charged out of the locker room, she ran smack into Nurse, who grabbed her and told her to slow down. She took Marjorie by the arm and led her right back into the room. Marjorie wiggled, trying to get loose, but Nurse held her tight as she told the other two girls to hold hands and follow. She looked at Marjorie, who was still wiggling trying to get away, and told her to stand still and that she could be her partner. She held Marjorie’s hand tightly as they walked towards the stairway at the end of the hall. These stairs led to the side door. Marjorie wanted to go down the middle staircase. She could call Joyce from there. She wiggled again, then stammered, and told Nurse that she just wanted to see Joyce — just for one second. She promised to be really quick.

Nurse had expected Marjorie to try to run to the kitchen to see her sister. The two girls were extremely close. It was going to be difficult for them to be separated, but it was not in her hands, so what could she could do about it? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. It piqued her, but she had to accept it. She told Marjorie that there wasn’t time and marched her ahead telling the other two to come along smartly, and no talking! Marjorie’s delight began to fade. Something was not right. As they reached the bottom of the stairs, a group of ten boys walked out the door.

Marjorie groaned and asked why the boys had to come, but Nurse did not answer. As they followed the boys out the door and under the four big white pillars, she could see Kenny at the rear of the line. Marjorie tried to get his attention, but he was too busy marching like a soldier. The kitchen window came into view as they rounded the end of the building. She could see Joyce, but she was not looking her way. Marjorie squirmed, trying to get free. If only she could run to the window to get Joyce’s attention, but Nurse held her even more securely. Marjorie yelled out as loudly as she could. It worked, and Joyce looked up. Marjorie waved frantically. Joyce saw her and waved back. Marjorie yelled even more loudly that she was going on an adventure and would see her later.

Nurse shook Marjorie and scolded her and said there would be no more talking. She warned her to look straight ahead and pulled her back into formation as they continued down the edge of the field. They walked past St. Mary’s Church at the bottom of the field, and along the little side path that led to Bristol Road. Marjorie was not happy that the boys were coming on their adventure, but she was glad for Kenny. He looked behind and gave her a little wave.

After walking for a while, Marjorie looked up at Nurse and said that she was hot and thirsty. She asked, “Are we going to walk the whole way? How much farther?” She wanted to know where they were going. Marjorie pulled off her tam and tugged at her buttons. She wondered why they had to wear their winter coats. The three girls looked at Nurse, but all she said was for Marjorie to hush and to stop asking questions. She told her to put her tam back on, button her coat, and that she would see all in good time.

They carried on down Bristol Road and crossed over at the bottom where the road forked at Oak Tree Lane. They stayed on Bristol Road, and as they walked over a little bridge, Marjorie recognized where they were. She looked up — it was the train station. The very same station they arrived at when they came from Newcastle all those months before. She read the sign — Selly Oak Station. Memories of her mother, of her sisters and brothers, and of Whitley Bay flooded back. An image of Newcastle loomed in her mind and the terror was as fresh as ever. Suddenly everything was clear to her. They were sending them back to Newcastle. It was a trick! Fear wormed its way up Marjorie’s spine. She dug in her heels, not wanting to get any closer. In a flash, she thought she could find her way back to the home if she broke free. She was a fast runner.

Nurse yanked at Marjorie’s arm and told her to stop pulling. She looked down at Marjorie and could see the fear in her eyes and her heart softened as she asked, “What is wrong?” Marjorie choked back her tears, and asked if they were sending them back to Newcastle. Marjorie’s comment puzzled Nurse — the children often came out with unreasonable and unexplainable fears. And, as it did now, it usually caught her off guard, but she knew it was important to put Marjorie’s fears to rest or it could turn into quite a scene. In her kindest voice she asked, “Newcastle?”

“Please, I’ll be good. Don’t send me there.”

“Marjorie, you are a silly girl at times. Whatever gave you that idea? We are not going to Newcastle.”

It was little reassurance, and as she was about to ask where was it they were going, the excited voices of the boys up ahead distracted her. She could hear them yell out, “Look, the train station. Are we going on a train today? Sir, sir, do we get to go on a train?” It was hard for Marjorie to hear the master’s reply, but there was a loud applause so she thought he must have said yes.

The children lined up along the platform while the master went to the ticket booth. It was difficult to stand still, for some because of the prospect of the exciting adventure before them, and for others because they were filled with uncertainty and dread. Trains were coming and going and people scurried in all directions. The master directed the children down the platform to wait for their train. They took the Selly Oak train to the Birmingham New Station, only to change trains there. As she boarded the next train, Marjorie wondered where they were going for their adventure and why it had to be a secret. Mistrust had piled up throughout the morning and now would not be shaken. The happy excited feeling from earlier in the day had all but disappeared.

Shortly after the train pulled away, Kenny ran up to Marjorie, a huge smile on his face, and announced, “Marjorie, Marjorie, we’re going to London! I always wanted to go to London.” Marjorie told her brother to be quiet and that they were not going to London. She turned to Nurse for confirmation, but she was busy and did not answer. A little girl sitting beside Marjorie whispered that she thought that he might be right. Kenny looked at his big sister and said that he told her so, and skipped back to his seat.

Fear and excitement mixed in Marjorie’s stomach. She remembered London on the large map at school, and it was in a different direction from the Newcastle home, so maybe Nurse was telling her the truth about not going back to that horrid place. It would be exciting to go on an adventure to London, but it was too bad that Joyce had to work in the kitchen. She would love to go to London. Marjorie would have so much to tell her when she got back. It was puzzling though. It must take a long time to get to London. Would they travel that far for their adventure? It would be very late when they returned and Joyce might even be asleep when she got back. She might have to wait until tomorrow to talk to Joyce.

Marjorie sat quietly, afraid to speak as the train sped south, taking them away from Birmingham. Most of the children busied themselves looking out of the window. At noon, Nurse passed around some lunch. The children ate quietly. The excitement had kept them from realizing how hungry they were. Marjorie took advantage of the quiet moment to get Nurse’s attention and told her that Kenny said they were going to London. She stood right in front of Nurse and said, “He’s wrong, right?”

“Well, umm, yes Marjorie. We are going to London,” said Nurse, lowering her eyes and her voice.

“Will we get back tonight? I promised Joyce …” Marjorie was cut off by Nurse. She appeared flustered and told the girls to hush, after scolding them for all their questions. She looked over at the master and asked him to please explain. The children all stopped what they were doing and looked at him. He finished his mouthful slowly, aware that all eyes were on him. Clearing his throat, he started, “Well, children, let me explain.” A sudden and total silence permeated the group.

He began by saying that he was certain that everyone had heard of Canada from their lessons at school. He looked around, “Put up your hand if you have heard of Canada.” All the children raised their hands, including those who did not have any idea what or where Canada was. It would do them no good to admit that they had not paid attention to their lessons.

“Good,” the master boomed out, “everyone knows where it is then.” He went on, “Canada is a colony of this great country of ours — on the other side of the huge Atlantic Ocean.” He told them that Canada was a very large country with not many people living in it. It needed good, smart, strong boys and girls like them to go over and help keep the country British.[1] He looked over his audience, and then continued. “Canada is a very beautiful country,” he said. “However, because it is so large, many people from the other countries want to go there too. We need to make sure the colonies stay British rather than have foreigners of all sorts moving in and taking over. The King has chosen you to be his little soldiers.” He told the children that each and every one of them had a very important job to do. He assured them that they would be very happy over in Canada, as this was a marvellous opportunity for all of them. He wiped his brow with his handkerchief and took another bite of his sandwich.

A stunned hush enveloped the car. This was no longer just a day trip. They would not be going back to the home. The questions started to fly. A boy challenged the master by asking if he had ever been to Canada.

He replied that he had not but he had heard a lot about it. He told them that there were cowboys and Indians in Canada and suggested that if were to look out of the train window when travelling across the country they might see some riding along on their horses. A wide-eyed youngster wanted to know if they were bad cowboys and Indians. The master replied, not reassuring anyone, “No, not at all.” He told them there was no need to worry and that they might even see some buffalo on the prairies as well.

“Buffalo! What are buffalo? Are they dangerous? Where are you sending us?” One of the taller boys stood up, demanding answers.

The master coughed; the bread suddenly felt very dry in his mouth. He surveyed the group and took note of the looks on the children’s faces. The expressions varied. He could see excitement, fear, and panic. He tried to answer only the questions from the children who appeared excited, but this quickly became impossible:

“How will we get there?”

“When will we be coming back?”

“How long will it take?”

“How long will we be gone?”

“But what about my sister? She is not here. I want her to come!”

“Hey, what about my little brother?”

“How will we get back?”

“What about my assignment at school? Do I have to finish that?”

“I am supposed to work in the kitchen on Saturday. Cook will be mad if I don’t show up.”

“Do we leave from London?”

“Is that why we are going to London?”

“My two sisters aren’t here. Will they be coming to Canada too? Is Canada close to London? I really want to go to London.” Kenny was going to get as many questions in as possible while he had the master’s attention.

Marjorie heard Kenny shout out. He asked the one question that she was too afraid to voice. “What about Joyce and Audrey? Why did we leave them back at the home?”

“Well, Kenny,” the master began, “we will be stopping at London. Who wants to see the lions at Trafalgar Square?”

Several children yelled out “I do! I do!” and drowned out the talk of brothers and sisters. Kenny kept asking about London. Not London, Marjorie screamed inside, ask about Joyce and Audrey!

Master told them that they would be stopping in London just for a night or two, and while there they would get to meet some real Canadian people at Canada House. “It’s a lovely big building right beside the lions at Trafalgar Square.” He warned them that they talk differently in Canada, so be prepared. He gave a little chuckle, but only Nurse laughed with him. Marjorie thought that was odd coming from him. She had had such a hard time at first understanding the Birmingham accents of everyone at the home. She could understand them perfectly now, as long as they talked slowly.

One girl asked if they were going to live at Canada House. Nervous laughter filled the car, but all faces turned to the master to see what he was going to say. He assured them that they would not be living there. He said, “From Canada House you will go over to Creagh House — a lovely old mansion in Kensington owned by the Fairbridge Society. They use it as a hostel. Then …” he began, but questions erupted again.

“What are we doing at Canada House?”

“Why are we going there?”

“My mum said she would come and get me from the home when she got better. Can she get me from Canada? I don’t think I want to go.”

“What if I don’t want to go either?”

“Can we come back from Canada if we don’t like it there?”

“Will I get to see my sister? I think she went to Canada.”

“Does my mum and dad know you are sending us there?”

“Is it really cold in Canada?”

“Is that why we had to wear our winter coats?”

“Who is going to look after us?”

“Do buffalo have big horns? Can they get us?”

“How are we going to get there?”

“Nobody asked me if I wanted to go. What if I want to stay in England?”

The master found it difficult to tell who was yelling out with questions coming from all directions and all at once. He raised his voice and told them to stop. “Put up your hand and ask one question at a time if you want me to answer.” He had fervently hoped that he and Nurse could keep the children occupied and their thoughts away from where they were going, then drop them off at Canada House and make their departure without this question period. He could see that he had better come up with some good answers, or they would have some very unhappy children on their hands. He surveyed the little group, assessing the impending mutiny. He asked them to be quiet and let him finish. He told them, speaking slowly, that from London they would travel to Liverpool. A lovely huge ocean liner, the Duchess of Atholl, would be waiting there to take them to Canada.

Marjorie asked if he and Nurse would be coming to Canada with them. But he shook his head, said “No,” and told her that they would take the children as far as Canada House and then go back to Birmingham. He smiled and told the children that he and Nurse were not as lucky as them, since neither of them could go to Canada. Bending towards them, and with a very serious note to his voice, he said, “Now, children, listen carefully. You are going to Canada House so that some Canadian people can meet you. Canada will not let just any children into their country, only the very good boys and girls.” He made them all promise him that they would be on their very best behaviour. “Promise me,” he urged. “It is for your King and your country.” The children had no choice but to promise. Master beamed his pride and said, “Good. Now, no more questions and finish your sandwiches.”

“But, sir, can we see Canada from Liverpool?” asked a little boy.

“Of course you cannot see Canada from Liverpool. It is too far away. Now, I said no more questions!” The master put his sandwich down and pulled out some papers from the case he was carrying and pretended to be busy with his work. He didn’t notice the look of alarm that spread over the children’s faces. They had already travelled so far from their families that most of them knew they would never be able to find their way home. Now he was telling them they were going across the great big ocean. How could any of them ever hope to make it back to their families from there? Dreaming of a visit from their mums and dads had kept many children from losing hope and now this hope was gone.

Marjorie’s appetite had vanished. She turned to Nurse and whispered. “If it is so far away, then we aren’t coming back ever, are we?” She wanted to know about her sisters Joyce and Audrey and her best friend Olive. She begged Nurse to go get them. “They should be with us. Don’t make me leave them,” Marjorie pleaded. Marjorie felt Kenny squeeze in beside her and take her hand, but she did not take her eyes off Nurse.

Nurse reminded Marjorie that Audrey was in sick bay. She told her that if she gets better, she might come out to Canada at a later date. She looked away, and said that Joyce had to stay at the home — the home needed her. Although Nurse told Marjorie and Kenny this, she knew that the Fairbridge Society had rejected their big sister Joyce because they thought she was too old for their program.

“You need her?” Marjorie’s tears flowed down her cheeks. “But I need her! She’s my big sister!”

Kenny looked at Nurse with his big brown eyes, “I need her too.”

Nurse had had enough and she told them so. “Some things are just the way they are.” She assured them that when they grew up they would understand, but for now, they just had to realize that the home knew what was best. She noticed that many of the children were watching and listening. She turned and swept her arm to include them all, as she suggested that the children would simply have to learn to accept things. They all should be thankful that they were chosen to go to Canada, “It will be a wonderful new life, so don’t be ungrateful for the chance you have been given.” Refusing to answer any more questions, she got up and sat near the master.

Marjorie sat back in her seat. “Damn it!” she said under her breath. “Goddamn and hell!” That was why they did not let her run into the kitchen this morning. Kenny was watching her. He warned her that she shouldn’t swear and that she would get into trouble. Then he asked her if he could finish her sandwich, as it didn’t look like she wanted it. As Marjorie handed it over to Kenny, she asked him why she should care if they hear her swear. Then she whispered to Kenny that she was going to jump up and swear her head off and then maybe Canada would not want her because she was too bad and then she would get to go back to the home to be with Joyce, Audrey, and Olive.

She began to get up on her seat whispering to herself the horrid things she would say, but she stopped when she looked at Kenny. His eyes were wide, staring back at her in disbelief, his mouth open. He warned her not to do it. It was then that it occurred to her that she was all her little brother had now. If they sent her back, they would not send Kenny back with her. He would be all alone. How could she leave him? Joyce told her how their mum made her promise to look after the three younger ones. She guessed now it was her job to look out for Kenny.

Marjorie sat back in her seat and let misery creep in. There was no excitement left for the day — this was not a good adventure. She wanted to go back home. If only she liked working in the kitchen more, maybe Nurse would have needed her too. But she could not leave Kenny. Marjorie fought away her tears. There was no point in crying. She was afraid, but Kenny’s worried face forced her to try to be brave for his sake.

An eerie quietness descended over the car. The children were lost in their own thoughts. Marjorie looked up as one of the girls walked up to Nurse and broke the silence. She wondered if she could ask just one more question, but carried on without waiting for a response and asked why she was told not to bring anything with her today, because if she is going to Canada, she should have brought her mother’s picture and her letters that were under her cot in her treasure box and she couldn’t get them now if she wasn’t going back to the home. “Why?” she whispered. “Will you send them to me? Do they have a post in Canada? You won’t make me just leave them will you? I have only one picture of me mum. I, I …” Her voice trailed off towards the end and tears were streaking down her face.

Nurse could see the tears spreading to the other children. Even the tougher boys were struggling. There was no sign of the morning’s jovial atmosphere. Not everyone agreed with the home’s policy of sending children off without letting them know where they were going. She hated lying to them. She had worked so hard over the past few months to build up their trust, but all seemed shattered now. She wondered what it was like for these children not to take their few precious belongings, not to say goodbye to good friends, and especially not to say goodbye to siblings. She had tried to imagine what that was like on several occasions, but it was impossible.

The home had strict guidelines in place and she had to work within them. It was believed that toughening up these little children was crucial to their survival. They could not be sent half way around the world unprepared for the rigours they would face. The home looked down on any sign of weakness, especially from the staff. They felt it harmed the children’s progress. The children needed to learn to be resilient. It would be a long, and perhaps rough, ocean passage, and then a long arduous train ride to the western shores of Canada. It would not be over then, because she knew that they needed to get on yet another boat before they reached their final destination. The Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School was on Vancouver Island, off the coast of British Columbia. It seemed so far away and so remote; the children could never imagine such great land spaces. That was probably one of the reasons they instructed her to tell them as little as possible.

“Let it sink in one step at a time,” the headmaster had warned. “That way the children might be able to cope with it. Keep them excited about what might be around the corner, and do not let them dwell on what they are leaving. You don’t want them crying all the way to Canada, do you?” The headmaster had growled as he dismissed her. But he had no advice about what to do when the children found that what was just around the corner too ominous to understand. Why had she been chosen to undertake this journey with the children? She had tried to get out of it, but to no avail.

Nurse hardly knew what to say to the girl. If she promised to send out something for one child, she would be making promises to them all, promises that she knew she could not keep. By now, the staff would have stripped their cots and all signs of these children would be gone from the dorm. They expected another group of children at the home any day now. It was even possible that by tonight a new group could fill the beds these children occupied this morning. The home tried to keep a steady stream coming and going. It was the policy.

It saddened her to think that they kept the children just long enough to fatten them up a bit. Most of the children would just start to settle in, find some security, and begin to trust her, and then they were gone. She wondered how these children really fared in their lives. Most of them came from backgrounds that left them unprepared for the harshness of emigration. The sending agencies expected these children not only to survive their ordeal but also to become perfect citizens in their new country. If they did not make it, they placed the blame on some weakness inherited from their poor parents. Everyone seemed to think it was the right and proper thing to do. It was cheaper than housing them in English institutions. They thought the best way to break the pattern of poverty and keep the children from following in their parents’ footsteps was to remove them from their backgrounds. To her, that was the tragedy — these children would no longer have any sense of family.

Unfortunately, this was precisely what most of the sending agencies saw as positive about child emigration. Once the children were removed from their parents they could mould them into good, useful, and obedient citizens. Yet, what actual changes were the children offered? For the most part they only trained them to be domestic servants and farm hands. They were simply preparing them for the same roles but in a different country, and there they had no family support. The children supposedly had the support of the Fairbridge Society, and it was believed to be far better than anything their families could give them, but she was not convinced. Maybe it worked. She rarely heard of them sending children back. Nevertheless, she felt that they expected the little children to undertake a journey that they would never embark on themselves. She was certain, too, that they would never, in a million years, consider sending their own children away on such a journey. This seemed to be the plight of the children of the country’s poorer classes. The poor had always been unwanted. She turned to the tear-stained child but could see that there was no need to respond. The little girl’s face showed that she already knew the answer.

By the time they pulled into London’s Euston Station, the mood had brightened a little. The children had heard of London, England’s capital, but had never expected to see it for themselves. The master shouted out orders for the children to line up on the platform and told them that they needed to take the Underground to Charing Cross. They were to find a partner, pay attention, and not get lost. He told them he hoped he had made himself perfectly clear but did not wait for a response before warning them that he would personally punish any of the children who let go of their partners’ hands. When he asked if everyone understood him, a chorus of “Yes, sir” rang out.

Getting everyone to the correct platform and on the Underground all in one group was a feat. Once they stepped inside the train, the children crowded around the door, making it impossible for others to get on. The master urged the children to keep going, to move ahead and find a seat. He counted them again, three girls and ten boys, and then breathed a sigh of relief — almost there and everyone was accounted for.

Their stop came quickly. The master ordered them to take their partners’ hands and follow him. “Be quick or the doors will shut and take you to the next stop.” Someone saw the sign and yelled out that they were at Charing Cross. The group marched out of the station, their eyes widening as they walked along Craven Street and then down Strand. They had never seen such sights and sounds before.

One of the four lions at Trafalgar Square, London. The children would have walked across the square in September 1937 to get to Canada House.

Photo by Jack Weyler.

“There’s Trafalgar Square! Can we get over there?” A boy yelled out.

It was a feat getting all the children across the street. For the past several months, they had spent all their time at the home, except for their daily monitored excursions to the local day school. Nurse was thankful when all were in the square and safe for the moment. Her obligations were almost at an end. She pointed and said, “Look, children, there’s Canada House.”[2] If all went as planned, she and the master could catch the late afternoon train back to Birmingham.

Squeals of delight rang out as the children ran around the square. It would not be wise to take them over to Canada House until they ran off a little energy. Two of the boys were sitting by one of the lions and yelling for someone to notice them. Master waved to them and told them to be careful. A younger boy chased the pigeons, but just when he thought he had one, the bird flew away, leaving him staring at his empty hands. The three girls wandered off and were walking arm-in-arm, staring about and looking agog at all the sights. A small group of boys stood by the statue of Lord Nelson.

“Blimey, that statue is high! I wonder who he is.”

Nurse was about to give a history lesson but was interrupted. It was unfortunate timing as it was one of those rare moments when the children seemed to have forgotten their plight and were living in the moment. The master’s voice broke the spell as he ordered the children to form partners again and line up. A groan broke out, but they scurried to comply. He counted them first, then walked up and down the line, inspecting each one, pointing to the child as he barked out his orders:

“Button your coat.”

“Put your hat on straight.”

“Pull up your socks.”

“Tuck in your shirt.”

It was important for the children to look their best before going into Canada House. His job was to ensure that the Canadian officials had no immediate grounds to reject any of the children.

“Now, boys and girls, we will be leaving you soon. You must be on your very best behaviour. You are getting to go on a grand adventure, but you must prove that you are worthy of such an honour. The King and your country expect you to be brave. Do not disappoint us. Alright, my little soldiers, line up by twos and follow me.”

Suddenly it hit Marjorie — it was important for her to make a good impression because if Canada did not want her, then who would?

The children marched to the far side of the square and waited for their chance to walk across the street. They clambered up the front stairs of Canada House.

“C-A-N-A-D-A. It spells Canada.” The girl beside Marjorie pointed to the letters at the top of the wall high above the columns.

As she scrambled up the foreign stairs, Marjorie longed for the familiarity of the home. She pictured Joyce looking everywhere for her. What would she think when she found out she was gone? Forever and ever. She had wanted to get away from Middlemore, but not like this.

In 2001, Marjorie visited Canada House with her grandson Jack Weyler, sixty-four years after she had been taken there in preparation for her departure for Canada.

Photo by Patricia Skidmore.