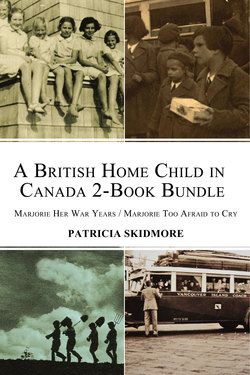

Читать книгу A British Home Child in Canada 2-Book Bundle - Patricia Skidmore - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One

ОглавлениеButterflies Prevail

Nervous. Pacing. Wandering abroad.

Wondering what? Wondering aloud ...

If there can be a resolution in this clime

For this loss carried over a lifetime?

Westminster Palace, London, England,

February 24, 2010

Emotions hung heavy, like late fall fruit dangling precariously in a forgotten orchard. Faces open, fearful, waiting; cheeks glistening with the ancient tears of pain held for years. For some, this pain was the only connection to their past.

Sixty-five or so men and women had been brought to London — back to their land of birth. They had waited a long time for this moment — their moment. Dressed in their town clothes, they mixed and mingled, nervously sharing bits of their stories. I, too, was there, having accompanied my mother to England.

“I was five, but my papers said I was three, and they changed my name. It made it hard to find my way back, you know.” One woman offered me this bit of information.

“Yes, I can only imagine.” I wanted to provide more, but what could I give? Besides, the woman had already moved away. It was an apology she was looking for, not my attention.

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown presenting a personal apology to the former child migrants brought to London for this occasion, on February 24, 2010.

Photo by Patricia Skidmore.

“They sent me to Australia and my brother to Canada. That wasn’t right you know, to split us up like that.” The man wore his uneasiness like a shield. “I had no one,” he muttered as he too walked away.

“I know. It happened too many times,” I replied after him.

I walked by an elderly man, cradling a framed photograph, his face lined with a record of a life long-lived. “It’s me mum,” he told me, pushing back a tear. “It took me twenty years to find her, and I only saw her just the once before she passed. Just the once.”

I found it difficult to know what to say. Others talked to me, but only in passing while they paced about. Wandering, waiting, wondering. Would they finally find what they were looking for? The room seemed crowded, but this group represented just a tiny portion of the whole number of children and families affected by Britain’s 350-year policy of migrating children to the colonies. Even though I knew better, I still found it difficult to believe that, at fifty-nine, I was older than some.

I kept my eye on my mother. Marjorie looked regal in her burgundy brocade jacket. Patient. She had been waiting for seventy-three of her eighty-three years for this moment. Nervous, stomach full of butterflies. Of this present group, it was just her and one other Canadian child migrant, along with three offspring and two spouses, invited to represent the more than 110,000 child migrants who had been shipped to Canada between 1833 and 1948.

The tone shifted and those in the room paused. I looked over as British Prime Minister Gordon Brown walked through the door.

February 9, 2010

I had arrived home in the evening to my partially packed house after a long, fruitless weekend of searching for a new home, to find an unexpected urgent message from Dave Lorente, the founder of Home Children Canada. “Can you come to the formal apology that the British prime minister, Gordon Brown, is giving to all British child migrants? It is just two weeks away. We need an answer tonight.”

The apology was an important issue for me, but never in my wildest dreams had I imagined that I might actually be present for it. I knew the event was imminent, because it had been announced the previous fall that Britain would follow the lead of the Australian prime minister, Kevin Rudd. In November 2009, Rudd had given a formal apology for the wrongs experienced by all children, including the child migrants who found themselves in his country’s care between the 1920s and the 1970s. I had been waiting for the date of Brown’s apology to be announced, but Dave’s call made it so that my mother and I were among the first to hear about it, since the event had not yet been formally publicized.

“Well, yes, I could go.” I heard myself say without hesitation. I could drop my house search, my packing, and everything else, and go to London. I listened intently to the details, then recalled that my passport was due to expire. I cradled the phone on my shoulder and dug through my papers searching for it. Just as I thought, it would expire before our return date. My mind immediately started to make lists. First, forget everything and race to the passport office in the morning, then …

“Pat, are you listening? Can you bring a home child?” Dave’s tone urged me to pay attention.

“A home child?” His question caught me off guard since I had always called my mother a “child migrant.” It was the children sent to the provinces in eastern Canada who were most often referred to as home children. But child migrants and home children were really one and the same. I came to my senses. “My mother?”

“Your mother! She is still with us? Can she still travel?”

“Oh yes indeed!” I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

“Absolutely perfect. The British High Commissioner here in Ottawa will be in contact with you in a day or two.” I listened to another twenty minutes of details, all of which I really wanted to hear, but I also wanted to hang up and phone my mother before she went to bed.

“Why are you phoning so late?” Marjorie sounded cautious, perhaps afraid of bad news that prompts calls in the dead of night.

“You will never guess. We have been invited to go to London to hear the British prime minister’s apology.”

“London, England? You are pulling my leg.”

“No, seriously, it is true. At least I think it is. It does seem a little unreal, doesn’t it?”

“Well, I can’t go. No. No, I just can’t drop everything and go. I have too many commitments. When does this take place?”

“It is scheduled for the twenty-fourth, which is two weeks tomorrow. We would have to leave by the twenty-first to have time to settle in before the big day.”

“No, I can’t.” Her voice determined.

“Well, can you at least think about it?” I begged, even though I found it difficult to be persuasive when I felt so uncertain myself.

“Yes, I will think about it. Goodnight.”

An email flashed on my computer as I hung up. More details of the trip, making it seem very plausible. I forwarded the email to my mother. Ten minutes later the phone rang.

“Okay, I will go.”

Letter from Malcolm Jackson, branch secretary, Fairbridge Farm School, June 11, 1940, to Marjorie’s mother. Jackson claimed that Marjorie asked for her siblings to join them at the farm school. When Marjorie saw this letter in 2009, she vehemently stated that she would never have said anything like that.

University of Liverpool Archives, Special Collections Branch, Fairbridge Archives, Arnison Family Records, D296.E1 .

I had always hoped for some formal recognition for the thousands of child migrants or home children sent to Canada. It was a little-known part of Canadian history. At one point there were up to fifty sending agencies in Britain shipping children overseas. While the numbers most commonly used for child migrants sent to Canada’s have varied widely from 80,000 to 100,000, Dave Lorente of Home Children Canada has pointed out that the Library and Archives Canada now has a list of 118,000 home children taken from ship lists that date back to 1865 at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/home-children/index-e.html. Many of the children had a difficult time accepting their new lives and all too often they found themselves in communities that did not fully accept them. A belief that the child migrants were of inferior blood led some of the new communities to not want these children to mingle with their own children. Home children were sent to Canada to work and then to find their own way once they were adults. It would not do to coddle them.

The farm school that my mother had been sent to was named the Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School. “Prince of Wales” was for the support the Fairbridge Society received from Edward, the Prince of Wales, and “Fairbridge,” after Kingsley Fairbridge, a man who advocated for the migration of Britain’s pauper children and for training them to become farmhands and domestic servants in the colonies. This farm school was established near Cowichan Station on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The children were housed in cottages that held between twelve to fourteen children. Each cottage was headed by a cottage “mother,” and the boys and girls were separated. Between 1935 and 1948 the farm school received 329 child migrants.

A number of these Canadian Fairbridgians claim that being sent to Canada was the very best of luck, however many of them do not hold that sentiment. As a daughter of a child migrant, and thus having experienced firsthand the effect it can have on families, I believe the system of migrating children to be fundamentally flawed. The family is the nucleus of our society, and it was precisely the family support system that was torn away from many of the children and replaced with something quite inferior.

Isobel Harvey, a B.C. child welfare worker in the 1940s, visited the farm school in 1944 and presented a nine-page report on the conditions she found at the Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School at that time. The cottages were, in Harvey’s opinion, “planned on an outmoded plan which allows the cottage mother little opportunity to foster any feeling of home … most of the children appear in aprons designed by the school clothing head, one might imagine they were residents of an orphanage in the last century.”[1] Harvey’s report was written almost two years after they sent Marjorie out to work as a domestic servant. It appeared that life at the farm school had not improved since her departure. For many of the children, the farm school cottage life did not provide a real place of belonging. The various cottages Marjorie was housed in and the numerous cottage mothers she was placed under were a poor substitute for her own family.

I wondered what effect an apology would have on my mother. Marjorie and three of her siblings had been removed from their mother’s care in early 1937. She strongly believed that removing her from her family and sending her to Canada as a child had not been the best thing for her or for her family. I tried to envision how it would be for my mother to actually be present when Gordon Brown gave his formal apology. Would it hold meaning for her? Would it speak to her “heart,” the heart that was broken nearly seventy years ago? Would the spokesperson, the British prime minister, be able to speak for the heart of Britain? After all, Gordon Brown himself was in no way responsible for the years of child migration.

I was aware that I had persuaded my mother to make this journey and if she could not find any meaning in Brown’s apology, then this trip could cause more damage and not bring her any resolution. It was not Brown who sent her away. Would his words be sufficient? Could his words touch her heart?

In the days leading up to our departure to London, I was asked numerous times: “What does this apology really mean? After all, it will only be a group of words uttered by a government spokesperson — it is nothing really concrete. It doesn’t change anything. It is a waste of money, time, and words.”

I never failed to reply, “If you are not the recipient, then how can you understand or begin to judge its merits or its effects on those who are directly receiving the apology?”

As for my mother, I truly wanted to believe that it could become a final resting place for her childhood grief, a time to replace any leftover stigma with a sense of pride, and a time to really see herself as the strong survivor that she was forced to become at such a young age. But there were no guarantees. I could just remain hopeful.

Others were stunned when I told them why Marjorie and I were going to London. Often they replied with something like this: “I consider myself well read and knowledgeable but I have never heard of child migration.” I would explain that the story of child migration had not been properly documented, nor taught in history classes. Many child migrants felt such shame that they would not talk about the circumstances of their removal from England and their subsequent childhood experiences. Individual instances are tragic enough, but strung together over centuries, the stories becomes unpardonable.

February 21, 2010

Marjorie and I boarded the plane in Vancouver, British Columbia, in the early evening of Sunday, February 21, 2010. We would arrive in London mid-day on Monday, giving us time to recover from our jet lag before the Tuesday evening reception, hosted by the Child Migrants Trust. We should be well rested and ready for the big day on Wednesday. My eighty-three-year-old mother, Marjorie, was a trooper, but this would be a taxing journey for her, especially as there had been so little time to prepare.

I sat next to my mother, tingling with anticipation. I had warned her that I wanted to share the manuscript I had written about her journey as a child migrant with her during this journey: our journey. Uncertain as to where to start, I decided to wait until the plane was safely in the air before beginning.

A Cloak of Shame

As the plane flew into the evening sky, I mulled about what this apology might mean to me. I was tired of feeling ashamed. As a young child, shame had buried itself into my very core before I was aware that such a thing was possible. For years I had been ashamed of my mother. She was ashamed of herself. We were nobody. We didn’t belong. The shame was so heavy that, as a child, I felt it covering me, my head, my shoulders, even obscuring my vision. I felt it was probably passed on to me in the womb. Shame had grown to be such a part of me that I had a hard time telling where it ended and where I started. I had struggled with it most of my childhood and was certain I had “daughter of a child migrant” stamped across my forehead for all to see. I could not erase it. My mother’s shame was my shame. Her rejection was my rejection.

I felt certain that Marjorie was hiding something from me. I hoped that it was for my own good. Up until I was a young adult, some part of me believed — the child in me perhaps — that if I tracked down where my mother came from, I’d discover that she was not my real mother and that I was someone else’s daughter. My real mother would come for me one day and all would be made clear. I just needed to be patient. That was my childhood fantasy. Certain that there must been have been a mistake, I expected the truth to come out one day. My survival depended on it. How could I belong to this family? We had nothing in common. I needed roots and I found none. My mother was no role model for me. I blamed her for not teaching me how to hope, to trust, to reach for the stars. I felt cheated. No one came to rescue me. My mother failed me. I was afraid of my future.

Regrettably, my fear came out as anger, and the distance widened between my mother and me. Now I wanted her to know that my childhood anger stemmed from fear, fear of the empty past she presented to me, and not from a lack of love for her. My anger, rooted in fear, was blinding and isolating. They say the truth will set you free, but it is not an easy process.

I looked over at my mother’s calm hazel eyes. She hated flying. It terrified her, yet you wouldn’t know from looking at her. It had taken me forever to recognize her calmness as one of her strengths. It would not be true to say that nothing fazed her, but, when threatened or attacked, she usually stood her ground without needing to lash out. I think she knew that my love for her ran deep, even when I did not know it myself. Writing her story has brought us closer.

The Whitley Bay sands with St. Mary’s Lighthouse in the background. Memories of playing on the sands and walking over to the lighthouse never left Marjorie.

Photo by Patricia Skidmore.

Realizing the difficulty I had chipping away at my own locked-up childhood helped me to gain a better understanding of why it was so complicated to pull out my mother’s hidden past — her buried memories and her painful secrets of rejection. She had years of experience to harden her past behind her cloak, to lose them, to act as if they didn’t exist. But it was her past, her childhood, that I wanted to know about. I wanted her to take my hand, to walk with me down that road, to show me, even at the risk of distressing her or finding the wrong things. I wanted to go back with her to revisit what it was like for her to be removed from her family and deported to Canada. I wanted to find the childhood that she had blacked out. I needed her to do this for me, with me, and I hoped that at the same time, she would find some healing as well.

Marjorie was born in Whitley Bay and lived there for the first ten years of her life. Whitley Bay is a seaside town on Britain’s northeast coast, just east of Newcastle upon Tyne. I wanted to go there, as I needed to imagine my mother as a little girl. I wanted to see where she was born, where she lived, where she went to school, and where she played. The first time I saw Whitley Bay, I thought it was beautiful. It must have been a grand place to grow up. The sand is spectacular. It is a seaside playground, and a far cry from the picture of a desolate slum that many sending agents claimed they saved the children from.

My mother — as a little girl — that part of her had eluded me for so long. I needed to see her as a whole person, someone with a life and past beyond me, and not just as my mother. When I began to have a picture of the little girl, the teenager, the young woman, who took the new life that was forced on her and did the best she could with the hand that she was dealt, it changed everything for me.

I sat with my thoughts and hugged my manuscript. It had taken me my entire life to gain an understanding of my mother and her story. It was important not to make any more mistakes. I glanced over at her. Her tightly curled hair, not nearly grey enough for her eighty-three years, framed her face. I looked for the child in her. I was beginning to see my mother with patience for her life that I knew I could never attain. And, even more remarkable to me, was that she accepted me: the demanding child, the stormy teen, and then my angry rejection of her as I chose to head into adulthood without her. She waited while I travelled through my early twenties, finally finding my way back to her. She had always accepted me. Why had I not been able to do the same for her?

The bond I felt now seemed new, yet I realized it had been there all along, buried safely, but often unreachable. I had learned from the best. Bury what you cannot understand. She had given birth to me, yet I felt I was not of her. Her answers were not right for me, so I rejected her. I was content to leave it that way for a long time. Then, with children of my own, my perspective on motherhood and family changed. How could I be a mother if I did not know how to be a daughter? I knew that if I were unable to accept my mother fully, I would not get to know her, or myself, not in the deeper way I needed. And then it would be perpetuated, as my children wouldn’t know me, not the whole me, which included my mother, their grandmother, with her child migration baggage unpacked and properly sorted.

My mother broke into my silent ramblings, “Can you start at the beginning?”

“The beginning?” I murmured.

“What did you say?” My mother’s hand went to her ear.

“Do you have your hearing aid turned on?” I raised my voice, feeling annoyed. She had the hearing aid, but all too often she turned it down because the amplified noise bothered her. I hated repeating myself. I hated that she was showing signs of her age. I hated that I had lost so much time wrapped up in my own anger.

I watched as she fiddled with the remote control device for her hearing aid. She winced. “There — are you satisfied? It’s on loud and clear.”

What had it been like for my mother as a child? She was sent away permanently from her family, from her country, at such a young age and expected to be grateful for such an injustice. The numerous sending agencies responsible for migrating children gave little thought to the fact that they were taking those children away from their families, not just their mothers and fathers, but all of their relatives. Dr. Alfred Torrie, a British psychiatrist, argued that “a bad home is better than a good institution.”[2] He thought that the evacuation of many thousands of children during the war years had shown some of the dangers of breaking up a family. The children he studied likely came from the wealthier families whose children were returned to them after the war. Nevertheless, it reinforces my belief of the importance of family for all classes. “Family” is not just a phenomenon set aside for the wealthy to enjoy.

I clung to my manuscript. I felt hesitant, shy even, to show my mother what I had written. I had carefully gathered the bits and pieces from her childhood in Whitley Bay and then little snippets from her six months at the Middlemore Emigration Home in Birmingham. I had reconstructed her journey from this home south to London, then up to Liverpool and over to Canada in September 1937. I gathered as much information as I could from her, from her brothers and sisters, from other former Fairbridgians, from school and government records, and from newspaper articles, in order to reconstruct what her journey to the Fairbridge farm school might have been like.

It was difficult to pull any memories out of her at first. It was as if her childhood was a black hole. When I was growing up, my frustrations stemmed from this blank area of our lives and that helped keep barrier between us. It took me ages to understand that my mother wasn’t simply keeping things from me, but that she had effectively blocked out so much of her childhood that she couldn’t find her way back there. It was as if our little family was starting from scratch. We had no past. Nothing to anchor us. This journey has helped me to deal with that. It is a coming to terms with things. It is an acceptance of my mother, and of me, instead of always wishing that it could be different. As a child, I longed to believe in a “switched at birth” story. As I grew older, my life and family did not seem to “fit” me. I wanted to wipe the slate clean and imagine any past but my own. Now I feel different, especially with a greater understanding of what my mother went through, what her childhood was like, and why she blocked so much of it out.

I wanted to tell her that I was proud to be her daughter, but the words were difficult to say. It has been a long journey, the countless hours in the bowels of the archives, the prying, digging, and uncovering information, piece-by-piece, transcribing interviews, writing numerous letters, searching on the internet, and emailing and writing to obscure places in England — always hoping for some response, some little piece of the puzzle. I often wonder what was driving me to figure it all out. And I know my mother has wondered that herself. I was aware of treading on territory that she had buried for a reason. However, I knew my mother was pleased about the newfound memories because, for the most part, they were good ones. Even the bad memories that I stirred up were easier to look at now, from this distance.

The turning point happened when I finally visited the Fairbridge farm school grounds near Cowichan Station in 1986. I had driven up and down Vancouver Island dozens of times, but it never occurred to me to take the road in to see where the school was located. I didn’t realize that I had a picture in my mind of the place, an image leftover from my childhood, and when I stood on the former Fairbridge farm school property, I was speechless. The vision of the farm school that I had in my mind was simply that of a gravel pit. I carried that image for years. I never questioned it. I was surprised to see such a beautiful valley before me. I suddenly realized that it was not where my mother grew up that left this image with me, but it was how she grew up. Her loveless childhood, her lost family, her state of mind, and her feelings about being taken away and having to grow up in this institution.

Whenever she would talk about the Fairbridge School, all I took away was a stark image of a desolate and lonely place. It was still not easy for me to explain to her how scary the stories of her childhood were for me. One of the most valuable things about my research is that, by finding out about my mother’s childhood, I have been allowed a parallel journey into my own. As I started to figure out who my mother was, what her childhood was like, what her mother was like and her brothers and sisters, I finally acquired a sense of family. I had found a place where I belonged. Suddenly, I had to have all the details about her. I needed to know exactly where she lived, what schools she went to, what streets she walked on, where she played. I needed to find out about the gate she recalled swinging on while she yelled out for a half penny on her tenth birthday. For me, all the magic of England is wrapped up in that one half penny.

“Are you telling me you wrote my story around a half penny?” My mother laughed when I told her.

“A half penny started it all, yes.” I admitted.

“And I would have settled for a farthing, but I didn’t even get that.” The sparkle in her eyes told me it was okay to keep going.

I began to see who I was. I was no longer the daughter of a child migrant; I was a daughter of a child migrant with a family history. I saw what she had been through, and my shame of being her daughter turned to feeling a tremendous pride. She survived her ordeal. She came away from it intact. They did not break her. They didn’t give her much education or feelings of self worth and they had deeply instilled in her that she was a British guttersnipe, but she kept going. And she kept her children going and she kept us together.

I was going to ask my mother to read my manuscript, her story, but I realized that I wanted to read it to her, with her. A sudden shyness almost overwhelmed me. I held my manuscript, hesitant to open it — to share it, even with this newfound friend of mine.

“I call this chapter ‘Winifred’s Children’ and it starts while you were still living with your mother in Whitley Bay. I wished I got the chance to know my grandmother. I think she must have been a strong woman to pick up the pieces and carry on the way she did.”

“I forgive her, you know, now that I realize that she didn’t just throw us away. I still blame my dad, though, and the government and the Fairbridge Society. How could they send us away?” Mom asked, obviously not expecting a satisfactory answer.

“This is the story I am going to tell to your great-grandchildren. I want them to know what it was like for you. You are an important part of Canadian history. Your experience and the experiences of the child migrants should be in the school history books.” I cleared my throat and prepared to present my findings.

A British half penny dated 1937, the year Marjorie left Whitley Bay and was sent to Canada.

Photo by Patricia Skidmore.