Читать книгу Lempicka - Patrick Bade - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Early Life

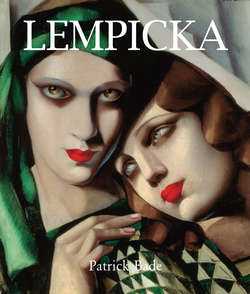

ОглавлениеPortrait of Baroness Renata Treves, 1925. Oil on canvas, 100 × 70 cm, Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

Tamara de Lempicka’s origins and her early life are shrouded in mystery. Our knowledge of her background is dependent upon some highly unreliable fragments of autobiography, and upon the accounts given by her daughter Baroness Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall to de Lempicka’s American biographer Charles Phillips. De Lempicka was a fabulist and a self mythologiser of the first order, capable of deceiving her daughter and even herself. Much of her story as told by her daughter has the ring of a romantic novel or a movie script and may not be much more authentic.

Both the place and the date of de Lempicka’s birth vary in different accounts. There is nothing more significant in the changing birth dates than the vanity of a beautiful woman (in Tamara’s time female opera singers with the official title of Kammersängerin had the legal right in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to change the date of their birth by up to five years).

According to some, de Lempicka changed her birth place from Moscow to Warsaw which could be more significant. There has been speculation that de Lempicka was of Jewish origin on her father’s side and that the deception over her place of birth resulted from an attempt to cover this up. Certainly the ability to reinvent oneself time and again in new locations, manifested by de Lempicka throughout her life, was a survival mechanism developed by many Jews of her generation. The prescience of the danger of Nazi Germany in a woman not usually politically minded and her desire to leave Europe in 1939 might also suggest that she was part Jewish.

The official version was that Tamara Gurwik-Gorska was born in 1898 in Warsaw into a wealthy and upper-class Polish family. Following three partitions in the late eighteenth century, the larger part of Poland including Warsaw was absorbed into the Russian Empire. The rising tide of nationalism in the nineteenth century brought successive revolts against Russian rule and increasingly harsh attempts to Russify the Poles and to repress Polish identity. There is little to suggest that Tamara ever identified with the cultural and political aspirations of the Polish people. On the contrary, she seems to have identified with the ruling classes of the Tzarist regime that oppressed Poland. It is telling that in 1918 when she escaped from Bolshevist Russia she chose exile in Paris along with thousands of Russian aristocrats, rather than live in the newly liberated and independent Poland.

The family of her mother, Malvina Decler, was wealthy enough to spend the “season” in St. Petersburg and to travel to fashionable spas throughout Europe. It was on one such trip that Malvina Decler met her future husband Boris Gorski. Little is known about him except that he was a lawyer working for a French firm. For whatever reason Boris Gorski was not someone that Tamara chose to highlight in her accounts of her early life.

From what Tamara herself later said, she seems to have enjoyed a happy childhood with her older brother Stanczyk and her younger sister Adrienne. The wilfulness of her temperament, apparent from an early age, was indulged rather than tamed. The commissioning of a portrait of Tamara at the age of twelve turned into an important and revelatory event. “My mother decided to have my portrait done by a famous woman who worked in pastels. I had to sit still for hours at a time… more… it was a torture. Later I would torture others who sat for me. When she finished, I did not like the result, it was not… precise. The lines, they were not fournies, not clean. It was not like me. I decided I could do better. I did not know the technique. I had never painted, but this was unimportant. My sister was two years younger. I obtained the paint. I forced her to sit. I painted and painted until at last, I had a result. It was imparfait but more like my sister than the famous artist’s was like me.”

Peasant Girl Praying, c. 1937. Oil on canvas, 25 × 15 cm, Private Collection.

The Polish Girl, 1933. Oil on panel, 35 × 27 cm, Private Collection.

If Tamara’s vocation was born from this incident as she suggests, it was encouraged further the following year when her grandmother took her on a trip to Italy. According to Tamara, she and her grandmother colluded to persuade the family that the trip was necessary for health reasons. The young girl feigned illness and her grandmother was eager to accompany Tamara to the warmer climes of Rome, Florence and Monte Carlo as a cover for her passion for gambling. The elderly Polish lady and her startlingly beautiful granddaughter must have looked as picturesquely exotic as the Polish family observed by Aschenbach in Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice. Visits to museums in Venice, Florence and Rome lead to a life long passion for Italian Renaissance art that informed de Lempicka’s finest work in the 1920s and 30s. A torn and crumpled photograph of Tamara taken in Monte Carlo shows her as a typical young girl de bonne famille of the period before the First World War. Her lovingly combed hair cascades with Pre-Raphaelite abundance over her shoulders and almost down to her waist. She poses playing the children’s game of diabolo but her voluptuous lips and coolly confident gaze belie her thirteen years. It would not be long before she would be ready for the next great adventure of her life – courtship and marriage. Played against the backdrop of the First World War and the death throes of the Russian monarchy, the story as passed down by Tamara and her daughter is, as so often in de Lempicka’s life, worthy of a popular romantic novel or movie.

When Tamara’s mother remarried, the resentful daughter went to stay with her Aunt Stephanie and her wealthy banker husband in St. Petersburg, where she remained trapped by the outbreak of war and the subsequent German occupation of Warsaw. Just before the war when Tamara was still only fifteen, she spotted a handsome young man at the opera surrounded by beautiful and sophisticated women and instantly decided that she had to have him. His name was Tadeusz Lempicki. Though qualified as a lawyer, he was something of a playboy, from a wealthy land-owning family. With her customary boldness and lack of inhibitions, the young girl flouted convention by approaching Tadeusz and making an elaborate curtsey. Tamara had the opportunity to reinforce the impression she had made on Tadeusz at their first meeting when later in the year, her uncle gave a costume ball to which Lempicki was invited. In amongst the elegant and sophisticated ladies in the Poiret-inspired fashions of the the day, Tamara appeared as a peasant goose-girl leading a live goose on a string. Barbara Cartland and Georgette Heyer could not have invented a ploy more effective for catching the eye of the handsome hero. In an account that has the ring of truth to it, Tamara admitted that the brokering of her marriage to Tadeusz by her Uncle was less than entirely romantic. The wealthy banker went to the handsome young man about town and said “Listen. I will put my cards on the table. You are a sophisticated man, but you don’t have much fortune. I have a niece, Polish, whom I would like to marry. If you will accept to marry her, I will give her a dowry. Anyway, you know her already.”

Peasant Girl with Pitcher, c. 1937. Oil on panel, 35 × 27 cm, Private collection.

The Peasant Girl, c. 1937. Oil on canvas, 40.6 × 30.5 cm, Lempicka’s Succession.

The Fortune Teller, c. 1922. Oil on canvas, 73 × 59.7 cm, Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

The Gypsy, c. 1923. Oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm, Private Collection.

By the time the marriage took place in the chapel of the Knights of Malta in the recently re-named Petrograd in 1916, Romanov Russia was on the verge of collapse under the onslaught of the German army and on the point of being engulfed in revolution. The tribulations of the newly married couple after the rise of the Bolsheviks belong not so much to the plot of a novel as of an opera, with Tamara cast in the role of Tosca and Tadeusz as Cavaradossi.

Given the background and life-style of the couple and the reactionary political sympathies and activities of Tadeusz, it was not surprising that he should have been arrested under the new regime. Tamara remembered that she and Tadeusz were making love when the secret police pounded at the door in the middle of the night and hauled Tadeusz off to prison. In her efforts to locate her husband and to arrange for his escape from Russia, Tamara enlisted the help of the Swedish consul who like Scarpia in Puccini’s operatic melodrama, demanded sexual favours. Happily the outcome was different from that of Puccini’s opera and neither party cheated the other. Tamara gave the Swedish consul what he wanted and he honoured his promise not only to aid Tamara’s escape from Russia but also the subsequent release and escape of her husband. Tamara travelled on a false passport via Finland to be re-united with relatives in Copenhagen. It was a route followed by countless Russian aristocrats, artists and intellectuals, often with hardly less colourful adventures than those of Tamara and Tadeusz. The beautiful and extremely voluptuous soprano Maria Kouznetsova, a darling of Imperial Russia, escaped on a Swedish freighter, somewhat improbably disguised as a cabin boy.

Refugees from the Russian Revolution fanned out across the globe, but Paris which had long been a second home to well-healed Russians, became a Mecca for White Russians in the inter-war period. Inevitably, Tamara and Tadeusz were drawn there along with Tamara’s mother and younger sister (her brother was one of the millions of casualties of the war). Unlike so many refugees who arrived there penniless and friendless they could at least rely upon help from Aunt Stefa and her husband, who had managed to retain some of his wealth and to re-establish himself in his former career as a banker.

From the turn of the century the political alliance between Russia and France – aimed at containing the menace of Wilhelmine Germany – encouraged the growth of cultural links between the two countries. The great impresario Sergei Diaghilev took advantage of this political climate to establish himself in Paris. In 1906, Diaghilev organised an exhibition of Russian portraits at the Grand Palais that pioneered a more imaginative presentation of paintings and sculptures. Following this success, he arranged concerts that for the first time presented to the French public the music of such composers as Glazunov, Rachmaninov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky and Scriabin. Young French musicians, yearning to escape from under the shadow of Wagner, were enchanted by this music that was fresh and new and not German. In 1908 at the Paris Opera, Diaghilev put on the first performances in the West of the greatest of all Russian operas, Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Paris was overwhelmed not only by the originality and barbarous splendour of Mussorgsky’s music, but also by the revelation of the interpretative genius of the bass Feodor Chaliapin. Chaliapin had terrified audiences standing on their seats trying to see the ghost in the famous Clock Scene and immediately established a reputation as the greatest singing actor of the age. Misia Sert, perhaps the most influential arbiter of fashionable taste in these years wrote “I left the theatre stirred to the point of realising that something had changed in my life.”

Woman Wearing a Shawl, in Profile, c. 1922. Oil on canvas, 61 × 46 cm, Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

Portrait of a Young Lady in a Blue Dress, 1922. Oil on canvas, 63 × 53 cm, Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

The following year, Diaghilev’s efforts climaxed in the presentation to the Parisian public of the Russian ballet. Parisians were dazzled by the dancing and choreographic talents of a company that included such legendary names as Nijinsky, Pavlova, Karsavina and Fokine and by the experience of ballet, not as trivial entertainment but as a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. Diaghilev and his ballet company continued to dazzle and astonish Paris for the next two decades. Diaghilev had an unparalleled talent for divining and developing the talents of others. Without mentioning the dancers and choreographers who created modern ballet under his aegis, the list of artists and musicians who worked for Diaghilev is a compendium of the greatest talent of the age and includes Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Richard Strauss, Satie, Falla, Resphigi, Prokofiev, Poulenc, Milhaud, Bakst, Goncharova, Larionov, Balla, Picasso, Derain, Braque, Gris, Marie Laurencin, Max Ernst, Miro, Coco Chanel, Utrillo, Rouault, de Chirico, Gabo, Pevsner and Cocteau.

Tamara de Lempicka’s career peaked in the year of Diaghilev’s death, 1929, and the trajectory of his brilliant career has relevance to hers in more ways than one. Diaghilev probably had more to do than anyone with establishing the myth of Russian creativity and exoticism in the arts. In later years when supplies of genuine Russian dancers were cut off by the Russian Revolution and Diaghilev was forced to use British dancers, he maintained their mystique by Russifying their names. So it was that Alice Marks became Alicia Markova, Patrick Healey-Kay mutated into Anton Dolin and Hilda Munnings became Lydia Sokolova after a spell under the unconvincing sobriquet of Hilda Munningsova. By the 1930s the idea that to be Russian was to be glamorous and exotic had permeated popular culture. In the 1937 version of the film A Star is Born, the young girl being groomed for stardom, played by Janet Gaynor is repeatedly asked by an employee of the studio publicity department if she has any Russian ancestry in the hope of creating a more exciting image for her.

Diaghilev’s designers, notably Leon Bakst, played a vital role in developing the Art Deco style with which de Lempicka became associated. In particular Bakst’s designs for the 1910 production of Sheherazade had an extraordinary impact on fashion and interior design. For the next generation, fashionable Parisian hostesses dressed themselves and decorated their salons as though for an oriental orgy. Even in the late 1920s, photographs of Tamara de Lempicka’s bedrooms show decors which, though much pared down from the lushness of Bakst’s designs, make them look as if Nijinsky’s sex slave would not be out of place as an overnight guest.

Paris in the inter-war period was teeming with Russian refugees. It was jokingly said that every second taxi driver in Paris was either a real or pretend Grand Duke. It was a situation that inspired the popular play Tovarich (turned into a Hollywood movie in 1937 starring Charles Boyer and Claudette Colbert) in which two former members of the Russian royal family are forced to earn a living as a butler and ladies’ maid in a wealthy Parisian household. A book on Parisian pleasures with charming Art Deco illustrations, entitled Paris leste commented on Russians partying in Paris, “you could think that there was a pre-war Russian party – that is to say a party where the Russians have money and a post-war Russian party, which is a party where the Russians don’t have money anymore. It’s the same thing! You find the same princes, the same imperial officers and officials in the same clubs. They’re doing the same thing. The only difference is that they used to be the clients and paid, whereas now they are employed by the house.” Tamara herself later claimed to be employing a couple of Russian aristocrats in disguise when she went to live in Hollywood.

Woman with Dove, 1931. Oil on panel, 37 × 28 cm, Private Collection.

Women Bathing, 1929. Oil on canvas, 89 × 99 cm, Private Collection.

Group of Four Nudes, c. 1925. Oil on canvas, 130 × 81 cm, Private Collection.

Apart from all the dancers, musicians and artists associated with Diaghilev already mentioned, there were numerous creative Russians intermittently or permanently resident in Paris. They included the conductor Sergei Koussevitsky, the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, the singers Nina Koshetz, Oda Slobodskaya, Natalie Wetchor and the entire Kedroff family, all of whom played an important role in the musical life of Paris and the artists Marc Chagall, Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Natalia Goncharova, Nadia Khodossivitch-Leger, Jacques Lipchitz, Serge Poliakoff, Chaim Soutine, Ossip Zadkine, Romain de Tirtoff (known, as Erté), Chana Orloff, Antoine Pevsner and, after 1933, Naum Gabo and Vassili Kandinsky.

De Lempicka’s early years in Paris were not happy. Though never reduced to the penury of so many of her refugee compatriots, she was nevertheless dependent upon the largesse of her wealthier relations. Despite the birth of her daughter Kizette, Tamara’s love match with Tadeusz was turning sour as a result of her own infidelities and his frustrations. He refused as demeaning the offer of a job in her uncle’s bank. According to her own account it was out of this grim situation and a desire for financial and personal independence that de Lempicka’s artistic vocation was born. Tamara confessed her plight to her younger sister Adrienne, resulting in the following conversation between the sisters; – “Tamara, why don’t you do something – something of your own? Listen to me, Tamara. I am studying architecture. In two years I’ll be an architect, and I’ll be able to make my own living and even help out Mama. If I can do this, you can do something too” “What? What? What?” “I don’t know, painting perhaps. You can be an artist. You always loved to paint. You have talent. That portrait you did of me when we were children…” The rest, as they say, is history. Tamara bought the brushes and paints, enrolled in an art school, sold her first pictures within months and made her first million (francs) by the time she was twenty-eight.

Once again, de Lempicka’s life, according to her own version, begins to sound like a bad movie script and it’s impossible to believe it can all have been that simple. A woman who continued to practice her art so doggedly long after it passed out of fashion and there was nothing practical to be gained from it, cannot have taken up her vocation in such a casual way and on such purely mercenary grounds. Nevertheless Tamara took herself for tuition to two distinguished painters in succession; Maurice Denis (1870–1943) and André Lhote (1885–1962).

The Sleeping Girl, 1923. Oil on canvas, 89 × 146 cm, Private Collection.

Seated Nude, c. 1923. Oil on canvas, 94 × 56 cm, Private Collection.

Nude, Blue Background, 1923. Oil on canvas, 70 × 58.5 cm, Private Collection.

De Lempicka later claimed that she did not gain much from Denis. It is indeed difficult to imagine that the intensely Catholic Denis would have been much in sympathy with the worldly, modish and erotic tendencies that soon began to display themselves in Tamara’s work. Nevertheless Denis was an intelligent initial choice as a teacher for the aspiring artist. For a brief period in the early 1890s Denis had been at the cutting edge of early modernism as a leading member of the Nabis group that included Vuillard, Bonnard, Sérusier, Ranson and Vallotton. Inspired by the synthetism of Gauguin’s Breton paintings, Denis and his friends broke with the naturalism of Salon painting and the very different naturalism of the impressionists who were tied to sensory perception and painted small pictures in flat patches of bright, exaggerated colours. In 1890 when he was only 20, Denis published his Definition of Neo-traditionism chiefly remembered today for its resounding opening statement, “It is well to remember that picture, before being a battle horse, a nude woman or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.” It is a statement that could be used to justify the formalism of modern art and even (something that Denis himself would never have accepted) the abandonment of the figurative in art altogether. After a visit to Rome in 1898 in the company of André Gide, Denis turned his back on modernism and was increasingly identified with classicism and with the reactionary Catholicism that was to have such a baleful influence on French cultural and political life in the twentieth century. It was perhaps his reputation for being associated with everything most retrogressive in French art that led de Lempicka to downplay Denis’ importance in her development. However the firm linearity and smooth modelling of the forms in Denis’ later works as well as his attempts to marry modernity with the classical tradition can hardly have failed to influence the young de Lempicka. The aesthetic expressed by Denis in his 1909 publication From Gauguin and Van Gogh to Classicism was surely one with which she would have agreed. “For us painters, our progress towards classicism was based on our good judgement in addressing art’s central problems, both aesthetic and psychological… we demonstrated that any emotion or state of mind aroused by a particular sight gave rise in the artist’s imagination to symbols or concrete equivalents which were able to excite identical emotions, of states of mind, without the need to create a copy of the original sight, and that for each nuance of our emotional make-up there was a corresponding object in tune with it and able to represent it fully. Art is not simply a visual sensation that we receive, – a photograph however sophisticated of nature. No, it is a creation of the mind, for which nature is merely the springboard.” This is surely true of de Lempicka’s strangely cerebral and abstracted portraits of the 1920s.

De Lempicka was far more ready to acknowledge the influence of her second teacher André Lhote. Whilst Denis must have seemed like a relic of the nineteenth century, Lhote born in 1885, was not much more than a decade older than de Lempicka herself and was much closer to her modern and worldly outlook. Lhote had been associated with cubism since 1911 when he exhibited at the Salon des Independents and the Salon d’Automne alongside artists such as Jean Metzinger, Roger de La Fresnaye, Albert Gleizes and Fernand Leger. Rather than following the radical experiments in the dissolution of form in Picasso and Braque’s Analytical cubism, he was attracted to the brightly coloured and more representational Synthetic cubism of Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger. For Lhote, painting was a “plastic metaphor…pushed to the limit of resemblance “ In words not so different from those of Denis, he maintained that artists should aim to express an equivalence between emotion and visual sensation, rather than to copy nature. What made Lhote particularly useful to de Lempicka as an example and as a teacher was the acceptance of the decorative role of painting, and also his attempt to fuse elements of cubist abstraction and disruption of conventional perspective with the figurative and classical tradition. It was significant perhaps that Lhote was the son of a woodcarver and that his initial training was in the decorative arts. Like Denis, he continued to be interested in decorative mural painting. His synthesis of cubist angularity and fragmentation with the academic tradition proved influential and helped to make cubism palatable to a wider public.

Seated Nude in Profile, c. 1923. Oil on canvas, 81 × 54 cm, Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

Nude with Sailboats, 1931. Oil on canvas, 113 × 56.5 cm, Bruce R. Lewin Gallery, New York.

The Two Girlfriends, 1930. Oil on panel, 73 × 38 cm, Private Collection.

Nude on a Terrace, 1925. Oil on canvas, 37.8 × 54.5 cm, Private Collection.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath, 1862. Oil on canvas, diameter 108 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

If the artist de Lempicka did not spring to life fully formed and fully armed like Athena from the head of Zeus as she would have us believe, the gestation period of her mature art was remarkably short – lasting two or three years at most. Her Portrait of a Polo Player painted around 1922 already shows her predilection for the smart set but could otherwise have been painted by any competent artist trained in Paris in these years. It has a looseness of touch and a painterly quality that would soon disappear from her work. The modelling of the face in bold structural brush strokes shows an awareness of Cezanne that would undoubtedly have been encouraged by both Denis and Lhote. Similarly lush and painterly is the portrait of Ira Perrot later re-titled Portrait of a young Lady in a Blue Dress. In its original form, as exhibited at the Salon d’Automne and photographed at the time with the model in front of it, it showed Ira Perrot seated cross-legged in front of cushions piled up exotically in the manner of Bakst’s Sheherazade designs.

More prophetic both stylistically and in subject matter than these two portraits is another canvas of the same period entitled The Kiss. The erotic theme, played out against an urban back-drop, the element of cubist stylisation that gives the picture an air of modernity and dynamism and the metallic sheen on the gentleman’s top hat all anticipate de Lempicka’s artistic maturity. The crudeness of the technique is as yet far from the enamelled perfection of her best work. Naivety is not in general a quality we associate with de Lempicka but this picture has the look of a cover for a lurid popular novel.

The following year we find de Lempicka working on a series of large scale and monumental female nudes that might be described as cubified rather than cubist. These works reflect an interest in the classical and the monumental that was widespread in western art following the First World War and throughout the inter-war period.

The entire history of western art from the Ancient world onwards can be seen in terms of a series of major and minor classical revivals. In an essay of 1926 entitled The Call to Order, Jean Cocteau presented the post-war return to classicism as a necessary reaction to the chaos of radical experimentation during the anarchic decade that had preceded the First World War. There was undoubtedly some element of truth in this, though the roots of inter-war classicism can be traced back much further.

Rhythm, 1924. Oil on canvas, 160 × 144 cm, Private Collection.

The Blue Hour, 1931. Oil on canvas, 55 × 38 cm, Private Collection.

Maurice Denis, The Vengeance of Venus.Psyche Falls Asleep after Opening the CasketContaining the Dreams of the Underworld, 1907. Oil on canvas, 395 × 272 cm, Hermitage St Petersburg.

A specifically French version of classicism can be seen as a continuing thread in French art running back as far as Poussin in the seventeenth century. The classicist most often cited in connection with de Lempicka is the nineteenth century painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). The taste for hard, bright colours and enamelled surfaces, the combination of abstraction and quasi-photographic realism, the eroticising of the female body through the radical distortion of anatomy and the love of luxurious and fashionable accessories link the female portraits of Ingres and de Lempicka. Baudelaire’s bitchy comment that Ingres’ ideal was “A provocative, adulterous liaison between the calm solidity of Raphael and the affectations of the fashion plate” could apply equally well to de Lempicka, What is perhaps more surprising is the way de Lempicka follows Ingres’ example in treating women as passive sex objects. Like Ingres she shows virtually no interest in the individual psychology or personality of her female sitters. De Lempicka’s female nudes are still more closely linked to Ingres. Her chained and swooning Andromeda with her upturned eyes and head thrown further back than anatomy should allow, against a cubified urban backdrop, is clearly an updated version of Ingres’ Angelica. Her groups of female nudes piled up like inflatable dolls, descend from Ingres’ notorious Turkish Bath.

Ingres’ reputation enjoyed a considerable revival in the inter-war period with the two giants of modern painting, Picasso and Matisse, each paying homage to him in their different ways. Another nineteenth century painter who was significant for the classical revival was Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898). In the 1870s just as impressionism, that most nonclassical of styles, was in full bloom, Puvis de Chavannes was developing through a series of monumental murals (often referred to as fresques but painted in oil on canvas) a style that attempted to embody the timeless qualities of classicism without falling into the cliches of the academic art on show at the Paris Salon. Puvis de Chavannes was a hero to the Nabis group. Denis would undoubtedly have urged his students including de Lempicka to follow Puvis’ example. Denis’ fellow Nabi Eduard Vuillard (1868–1940) wrote “The experiments in stylisation and in expressive synthesis of form which are typical of today’s art were all present in the art of Puvis.”

The crisis of confidence suffered by all the impressionists to a greater or lesser degree in the 1880s caused Renoir to turn back to the classical tradition. A trip to Italy from 1881 to 1882 during which he studied Roman wall painting and the Renaissance masters, prompted Renoir to look with renewed interest at Ingres, an artist hitherto regarded as an anathema by most artists of the Impressionist group. In the mid 1880s, Renoir developed a hard-edged style that in turn gave way to the softer but volumetric and monumental style of his later years that had considerable impact on the classicising painters and sculptors of the inter-war period. It was the simple lines and large sculptural volumes of Renoir’s late nudes that encouraged Aristide Maillol to break with the pathos and “unsculptural” qualities of Rodin’s expressively modelled sculptures. The key work for the re-launching of a monumental classical style in twentieth century sculpture was Maillol’s La Méditerranée modelled in 1902 and exhibited in bronze in 1905 in the very same Salon d’Automne that saw the controversial debut of the Fauve group. It could be argued that Maillol’s monumental neo-neo-classicism had a longer lasting impact on western art than the spectacular but short lived Fauve movement which could be seen as a glorious coda to the nineteenth century but something of a dead end. It was unfortunate for Maillol’s reputation and indirectly for a while at least for de Lempicka’s that Maillol’s best known pupil was Hitler’s favourite sculptor Arno Breker and that the kind of monumental classicism pioneered by Maillol and practised by de Lempicka became so closely associated with totalitarian regimes of the 1930s.

The return to classicism regarded by some followers as a betrayal and even a blasphemous provocation was given the stamp of approval by the king of the Parisian avant-garde Pablo Picasso. As early as 1914 (thus well before there was any question of reaction to the consequences of the war) Picasso began toying with some aspects of classicism, making portrait drawings based on photographs in a hard linear Ingresque style. A good example is the portrait of the art-dealer Léonce Rosenberg made in 1915, that is very reminiscent of the kind of drawings Ingres made of tourists in post Napoleonic Italy. Though de Lempicka was scathing about Picasso, paintings such as the Seated Nude of 1923 depicting a woman with colossal thighs and sculptural breasts, show a clear awareness of Picasso’s work – both the primitivism of the early analytical cubist phase and the gigantic neo-classical female figures of the post war period.

In the close and somewhat incestuous artistic and intellectual circles of Paris between the wars, it was inevitable that de Lempicka would have come into contact with most of the leading artists and intellectuals. Amongst the artists and writers she mixed with were Gide, Marinetti, Cocteau, Marie Laurencin, Foujita, Chagall, Kiesling and Van Dongen. Cocteau, who warned her that she risked ruining her art by too much socialising, would have provided her closest contact with Picasso. Cocteau’s own dazzlingly clever and sophisticated erotic drawings would have provided de Lempicka with an example of how to combine the avant-garde, the classical and the slickly commercial. Lifting nude male figures straight from Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling and other Renaissance and classical sources, Cocteau added the enlarged genitals, curling pubic hair and other attributes of homosexual pornography, all drawn in a spare linear style closely based on Picasso’s neo-classical drawings. The result is Michelangelo and Picasso crossed with Tom of Finland. If the eroticism in de Lempicka’s work is never quite as blatant as Cocteau’s she certainly managed to achieve a similar synthesis of the modern, the illustrational and the commercial in her mature work of the late 1920s.

In an article published in 1929, the distinguished French critic Arsène Alexandre remarked upon the successful synthesis of classical and modern in de Lempicka’s work, exclaiming “What singular, happy contradictions enable her to convey the impression of such modernity (intense modernity, in my view) while using such purely classical resources? With the apparently chilly style that she sometimes pushes to extremes, by what means can she suggest feelings (not to mention sensations) that are generally connected with the opposite pole? How can she shift from the expression of chastity, unless of course we find it difficult to distinguish one from the other?”

Suzanne Bathing, c. 1938, Oil on canvas, 90 × 60 cm, Private Collection.