Читать книгу Lempicka - Patrick Bade - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

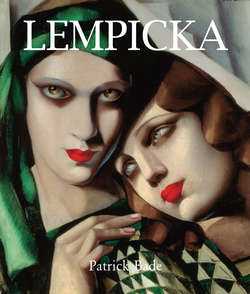

Art Deco

ОглавлениеSharing Secrets, 1928. Oil on canvas, 46 × 38 cm, Galleria Campo dei Fiori, Rome.

Georges Lepape, Cover of Vogue, 15 March 1927.

The “intense modernity” and “chilliness” of de Lempicka were both expressed through a devotion to the mechanical and the metallic that are characteristic of the period. One of the most distinctive aspects of de Lempicka’s art is the way she paints everything from human flesh to permed hair and crumpled drapery with metallic sheen. One is reminded of Manet’s cutting remark on the military paintings of Ernest Meissonier, that everything looked as though it was made out of metal except the weapons. In de Lempicka’s work though, the metallic quality comes from an aesthetic that is in thrall to the machine.

As industrialisation spread through the western world in the nineteenth century, the machine began to influence every area of human endeavour. Many artists reacted initially with horror. The French Symbolist painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes suffered from nightmares after visiting the Hall of Machines in the Paris World Exhibition in 1889. For William Morris, the most influential design theorist of the late nineteenth century, the machine represented a threat to everything he held dear. He could not see that the machine could in fact enable the fulfilment of his desire for art and prosperity for the people. It was not until after the turn of the century that architects and designers such as Richard Riemerschmid and Peter Behrens began to perceive the machine as opportunity rather than a threat. Fine artists also began to find machines exciting and beautiful. In the Futurist Manifesto, published in the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909, Marinetti proclaimed the advent of “a new beauty… a roaring motorcar, which runs like a machine gun, is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace.” When sitting with Marinetti in the Brasserie La Coupole, de Lempicka became so excited by his rhetoric that she found herself part of a mob chanting “Burn the Louvre.” She claimed that she was only thwarted in this plan by the fact that the police had impounded her improperly parked car.

The Futurist Manifesto stated “We wish to glorify war.” Certainly the First World War, with mechanized warfare on a hitherto undreamed of scale and the industrialisation of death, while it put paid to the Futurist movement, represented a grim triumph for the machine. The reaction of the painter Fernand Léger, who took part in the war as a common soldier was to move towards an art that was more populist and a style that was profoundly influenced by the aesthetic of the machine. He began painting shiny metallic forms that are not unlike those of de Lempicka.

The Green Turban, 1929. Oil on panel, 41 × 33 cm, Private Collection.

The Girls, c. 1930. Oil on panel, 35 × 27 cm, Private collection.

In the inter-war period, the cult of the machine permeated every aspect of culture and society. Motor cars, express trains, aeroplanes, zeppelins and ocean liners replace nymphs and caryatids as decorative motifs on the façades and ceilings of department stores such as Barker’s in London and Bullocks Wilshire in Los Angeles. Le Corbusier described a house as “a machine for living in.” Buildings such as Broadcasting House in London and the Coca-Cola bottling plant in Los Angeles took on the appearance of immobilised ocean liners, while ocean liners such as the Ile de France, the Normandie, the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth represented the aspirations and ethos of the Art Deco period in a way that cathedrals had done for the Middle Ages and museums and railway stations for the nineteenth century.

Even in films such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis of 1927 and Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times of 1936 that aim to warn against the dangers of mechanisation, it is clear that the designers were completely in thrall to the aesthetic of the machine. A naïve and exuberant enthusiasm for the machine is expressed in Hollywood musicals of the Busby Berkeley type in which hundreds of girls in massed formations and all looking as though they themselves have been mass manufactured, move like cogs in a vast machine. The most delightful Hollywood tribute to the aesthetic appeal of the machine is the sequence in the 1937 RKO movie Shall we dance in which Fred Astaire dances to the rhythm of the pistons in the shining and immaculately clean engine room of an ocean liner.

Music too, was affected by the love of machines, from the motoric rhythms of avant-garde composers such as Stravinsky and Hindemith and the near pictorial evocations of machines in concert pieces such as Alexander Mosolov’s Iron Foundry and Arthur Honneger’s Pacific 231 (that simulates the sounds of an accelerating locomotive) through to the popular dance bands of the period such as Wal-Berg in Paris that loved to mimic the sounds of express trains and urban traffic.

By the 1930s, the machine and mass production had brought just the kind of democratisation of good design of which William Morris had dreamed. Anyone visiting a flea-market can pick up 1930s mass produced objects in industrial materials such as bakelite and chromed metal that are as sleek and aesthetically satisfying as the most luxurious products of the period. The mass produced objects of the art nouveau period always looked like shabby and cheap imitations of expensively handcrafted pieces. But in an interesting reversal, the most prestigious and expensive craftsmen of the Art Deco period such as the ebonist Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann used the most labour intensive techniques and the most precious materials to reproduce the simple streamlined forms of industrial design.

The smooth reflective surfaces of the Art Deco style that we see throughout de Lempicka’s best work and in particular in works such as Arlette Boucard with arums of 1931 with its glass topped table and transparent vase, also express a new found desire in western culture for hygiene. The idea that “cleanliness is next to godliness” had not been central to Christian culture prior to the nineteenth century (unlike Jewish and Muslim traditions that had always put great emphasis on personal hygiene). After the notion of germs and the connection between health and hygiene had been established by Louis Pasteur and others in the mid nineteenth century, cleanliness and bathing received greater emphasis in Europe too. As late as the 1880s when the luxurious Savoy Hotel was built in London, eyebrows were raised at the quantities of en suite bathrooms. But by the inter-war period every middle-class household included a bathroom, that was likely to be the most modern and best designed room in the house with germ-free ceramic, glass and chromed metal surfaces. Lavish bathrooms figure largely in the movies of the period. Unfortunately the publicity photos of de Lempicka’s rue Méchain apartment do not show her bathroom, but from the design aesthetic of the rest of the interiors we can well imagine what it must have looked like.

The Orange Scarf, 1927. Oil on panel, 41 × 33 cm, Private Collection.

La Belle Rafaëla in Green, 1927. Oil on canvas, 38 × 61 cm, Private Collection, Paris.

Double “47”, c. 1924. Oil on panel, 46 × 38 cm, Private Collection.

Alfred Wolmark, Double portrait.Oil on canvas. Victor Arwas Gallery, London.

One of the most iconic images of the Jazz Age and perhaps de Lempicka’s most frequently reproduced picture is the self-portrait at the wheel of an open-topped Bugatti sports car in de Lempicka’s favourite “poison green”, commissioned by the German Fashion magazine Die Dame in 1925. The tight driver’s helmet that masks her permed blond hair and makes her look more like an aviator than a motorist, and her cool impervious stare characterise her as a thoroughly independent and self-confident modern woman. Like the sewing machine and the type-writer in the previous generation (that provided employment however humble inside and outside the home), the motor car contributed significantly to the emancipation of women, if only those at the upper end of the economic scale.

De Lempicka monogrammed this picture with her initials, looking like an industrial logo on the door of the car. Throughout the Art Deco period de Lempicka showed her allegiance to the machine aesthetic by signing her pictures in printed letters that look like industrial typeface in contrast to the flowing calligraphy favoured by the more painterly artists of the Belle Epoque.

As Arsène Alexandre suggested, de Lempicka’s modernity also lay in her combination of coolness and sensuality and a certain ambiguity. Though he is too discreet to spell it out, this ambiguity was sexual.

Amongst the value systems that had been thrown into question by the unparalleled catastrophe of the First World War were traditional concepts of gender. The 1920s in Paris might be termed a heroic age of Lesbianism. Back in the nineteenth century when Queen Victoria reputedly denied the existence of lesbianism, it flourished in the brothels of Paris, if we are to believe the clandestine guide-books produced for English speaking sex tourists to the City of Light. In 193 °Colette began publishing a series of essays in the Parisian weekly Gringoire that were eventually collected and published in book form under the title of The Pure and the Impure, in which she revealed the shadowy life of well-healed lesbians in the early years of the century. Though the initial run of articles was interrupted, apparently in response to negative responses, the very fact that such a well-known and respected author could publish such material showed the profound change of attitudes towards homosexuality and lesbianism that had taken place since the First World War. The war itself had much to do with this. When millions of young men departed for the slaughter of the western Front, women were forced into new roles and many were released from domestic slavery. After the war there was no turning back. Changing roles were reflected in the changing appearance of women – bobbed hair and la ligne à la mode – boyish figures with flattened breasts and narrow hips. Throughout the western world popular songs such as Masculine men and feminine women or Eh! Ah! Maria! T’est’y une fille ou bien un gars? and Hannelore (with her pretty boys haircut and smoking jacket who has “a bridegroom and a bride” in Claire Waldoff’s song) mocked or celebrated the new androgynous look. Berlin was the capital in which traditional sexual mores and gender roles broke down most spectacularly. According to Stefan Zweig “Berlin transformed itself into the Babel of the world. Bars, amusement parks and pubs shot up like mushrooms – made up boys with artificial waistlines promenaded along the Kurfurstendam – and not only the professionals. Every high school pupil wanted to make some money and in the darkened bars one could see high public officials and financiers courting drunken sailors without shame. Even the Rome of Suetonius had not known orgies like Berlin’s Transvestite balls. Amid the general collapse of values, a kind of insanity took hold of precisely those middle-class circles which had hitherto been unshakable in their order. Young ladies proudly boasted that they were perverted. To be suspected of virginity at the age of sixteen would have been considered a disgrace in every school in Berlin.” If Berlin was notorious for its transvestite balls, Paris was undoubtedly the lesbian capital of the world in the 1920s. The relative acceptance of lesbianism in inter-war Paris allowed for the opening of well-known lesbian night spots such as Le Monocle and sympathetic and even glamorous representations of lesbians in French movies such as Symphonie Pathétique in 1928 and La Garçonne in 1936. This tolerance attracted to Paris creative and unconventional women from all over the world. Gertrude Stein and Alice B.Toklas and Nathalie Barney and Romaine Brooks, the best known Parisian lesbian couples had been in the city from before the war and they were joined there in the 1920s by the novelist Djuna Barnes, the journalist Janet Flanner, Sylvia Beach, proprietor of the famous English language bookshop Shakespeare and Co. De Lempicka dismissed Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway as “boring people who wanted to be what they were not. He wanted to be a woman and she wanted to be a man.” She did attend the salon of Nathalie Barney and Romaine Brooks, but with her frivolous and somewhat snobbish hedonism it is difficult to imagine de Lempicka attending book readings at Adrienne Monnier’s La Maison des Amis des Livres or contributing much to the feminist or lesbian intellectual life of Paris. Long before the term was invented, de Lempicka might have been described as a “Lipstick lesbian.” However she did take her role as a woman artist seriously enough to exhibit with the group FAM (Femmes Artistes Modernes) in the 1930s.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу