Читать книгу French Guiana - Patrick Chamoiseau - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

CHARLES FORSDICK

The absence of memorialization of the bagne is one of the most striking examples of postcolonial amnesia in the French-speaking world. Omitted—like most other locations relating to colonial expansionism—from Pierre Nora’s Realms of Memory project (the seven volumes of which appeared between 1984 and 1992), the penal colony epitomizes the ways in which memories of colonial empire have been filtered, distorted, singularized, and often repressed. The bagne constituted nevertheless a carceral archipelago, a network of sites scattered across France itself (where prisons in the port cities of Brest, La Rochelle, and Toulon were complemented by penal colonies for young offenders), North Africa (location of the infamous “Biribi” or military prisons and forced labour camps), and elsewhere in the colonial empire (most notably French Guiana, New Caledonia and Vietnam).1

French Guiana had served as the destination for political dissidents during the French Revolution, but it was in 1854 that Napoleon III signed a decree relating to forced labour that turned the South American colony into a formal penitential destination for civil transportees from France and the wider French colonial empire.2 (They would as a result of legislation in 1885 be joined also by recidivists, prisoners guilty of repeated petty crimes.) The logic and function of the penal colony were clear: on the one hand, it permitted the location far from France or other colonies of those considered politically and socially undesirable; on the other, it provided the workforce for the colonization of a country that had proved (and would continue to prove) stubbornly resistant to imperial expansionism and settlement. The conditions were harsh, for convicts, warders, and colonial administrators alike, even on the supposedly more salubrious Salvation’s Islands where the impact of tropical diseases was reduced. Prisoners were moreover subject to a regime of doublage, meaning that convicts sentenced to less than eight years of hard labour were obliged to remain in French Guiana for a period equal to their original sentence whilst those sent for more than eight years were exiled for life.

The mortality rate was such that, from 1864, French metropolitan convicts were diverted to the newly established penal colony of New Caledonia. The bagne in the Pacific operated for little more than sixty years, with transportation to there ended in 1897 after only three decades. The penal colony in French Guiana continued to function throughout this time, receiving convicts from elsewhere in the French colonial empire. With the closure of the penal establishments in Melanesia, metropolitan prisoners were again dispatched to South America. A campaign of reform triggered by the work of investigative journalist Albert Londres in the 1920s led, however, to the passing of legislation in 1938 that formally ended penal transportation. Another key text, by the Guianese author and leading figure in the Negritude movement Léon-Gontran Damas, pointed to the failure of the bagne. Retour de Guyane, published in 1938, provided such an incendiary critique of the penitentiary and the colonial structures with which it was inextricably bound that the French Guianese authorities seized and destroyed as many copies of the book as they could. This was not, however, the end of the penal colony. French Guiana was under the control of Vichy in the first years of the Second World War, during which time the conditions under which convicts lived rapidly deteriorated—the former French Minister of Justice Robert Badinter went so far as to claim in 2017 that this treatment constituted a crime against humanity.3 Repatriation of surviving French prisoners took place between 1946 and 1953, with some Algerian prisoners not returning to their country of origin until the early 1960s.

Unlike the penal colonies in Australia, the French Guianese bagne consequently remains a phenomenon of recent history, meaning that memory debates relating to it have much closer resonance with the present. It is telling, therefore, that the institution has been subject to progressive amnesia despite its everyday visibility in the built environment: many historic public buildings and much of the infrastructure in French Guiana were built with convict labour; whilst subject to processes of postcolonial ruination, other sites of the penal colony itself have persisted and it is these structures that form the focus of the book that follows.

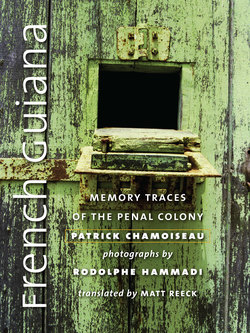

French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony is a hybrid work, a photo-essay in which text and image are juxtaposed in ways that are more suggestive and disruptive than prescriptive.4 Patrick Chamoiseau’s essay in which he elaborates the notion of the “memory trace” sits alongside a selection of photographs of various penal sites by Rodolphe Hammadi, a French photographer of German and Algerian heritage. The book appeared initially in modest paperback format, published in 1994 by the Caisse nationale des monuments historiques et des sites, in a collection entitled “Monuments en parole” devoted primarily to French metropolitan heritage locations such as Notre-Dame in Paris or the Grand Théâtre in Bordeaux. Chamoiseau’s texts were republished in a more sumptuous coffee table version by Editions GANG in 2011, retitled Bagne AP and accompanied in this version by the photographs of Jean-Luc de Laguarigue. The volume initially appeared in the context of significant memory debates in France, focused not least around the bicentenary of the French Revolution in 1989. The place of the colonial past in these processes remains moot, despite the importance of the Caribbean colonies in seeking to link liberté, égalité, fraternité to a push (successfully, in the case of Saint-Domingue or Haiti) for universal emancipation from slavery.

In the early 1990s, when this book first appeared, the apparatus supporting penal heritage in French Guiana was limited, part of a more general process—which Chamoiseau himself identifies — that consigned the institution to oblivion. By then, there was already limited dark tourism to Salvation’s Islands, sites administered since the 1960s by the Space Centre at Kourou in a striking juxtaposition of two radically different experimental projects.5 Other key locations of the penal colony remained at the time underdeveloped, however, either subject to the encroachment of nature (as was the case with the so-called bagne des annamites at Montsinéry-Tonnegrand, built for Indochinese political dissidents in the 1930s) or serving as repurposed or inhabited heritage (strikingly the case with the Camp de la Transportation at Saint-Laurent du Maroni, still partly occupied—when Hammadi took his photographs—by refugees of Maroon origin exiled by neighbouring Suriname’s civil war).6 Chamoiseau is acutely aware, however, of dominant official memory practices, particularly those privileging colonial, political, and military officials evident in statues and plaques in French Guiana (the monument to abolition in Cayenne, showing the generous Victor Schoelcher granting the gift of freedom to a grateful formerly enslaved young boy is a classic illustration of this), and eclipsing persistent yet often silenced oral memories. He alludes at the same time to more informal processes of amnesia, not least the place of the penal colony in the popular imaginary, according to which convicts are associated with “celebrity” prisoners or at least seen exclusively as ethnically white.7 His response is the search for alternative “memory traces,” presented by Chamoiseau as “broken, diffused, scattered,” but stubbornly discernible to those willing to look more closely and listen more attentively.

Hammadi’s photographs cover a range of different sites: Alfred Dreyfus’s dwelling on Devil’s Island; the administrative and prison buildings on Royale Island; the overgrown cell blocks of the bagne on Saint-Joseph’s Island; the remaining brick pillars of the Camp de la Forestière near Saint-Laurent du Maroni, accessible only with the aid of a machete and a knowledgeable local guide; Saint-Joseph’s church at Iracoubo, decorated with the murals of convict Pierre Huguet. Together, these images reveal the dangers of reducing the word bagne to a single site (the French often misleadingly talk about the “bagne de Cayenne”) or to a single history.

Chamoiseau describes his engagement with these places, his decipherment of graffiti and other faded inscriptions discovered in them, his interrogation of their silences, his affective response as suppressed memories emerge. The place of French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony in Chamoiseau’s wider oeuvre is significant. The author’s interest in penal cultures is not limited to this text: the novel Un dimanche au cachot (2007) uses a palimpsestic understanding of space, for instance, to create links — through the story of its troubled young female protagonist—between an eighteenth-century cell for the enslaved and the children’s home that occupies the site now.8 This relationship between memory and the persistent traces of different cultures of incarceration is equally pertinent for the current text. Memory Traces appeared five years after the co-authored manifesto In Praise of Creoleness, a call for more active recognition of the cultural and linguistic heterogeneity of the French Antilles.9 It was published only two years after the writer’s novel Texaco had been awarded the Goncourt Prize.10 The photo-essay on French Guiana continues the logic of those works, on the one hand by opening heritage debates up to the cultural and ethnic diversity underpinning creoleness, on the other by engaging in a recovery of those voices often systematically silenced by officially endorsed narratives of the past. His approach was to read the vestiges of the penal colony as evidence of ruination, a process explored by Ann Laura Stoler, who sees such a metaphor of the links between the colonial past and postcolonial present as preferable to more linear and common evocations of colonial legacy.11 The ruin becomes organic, a reflection—through layers of moss, damp, soil, and dust—of the oblivion to which state-sanctioned memory appeared to have condemned the penal colony, but also a space of counter-memory, a repository of intersecting traces of the past—of “the histories of the dominated and demolished memories”—reactivated through the rhythms of the walking of the attentive wanderer who encounters them afresh. Steering away from the pitfalls of what is known increasingly as “ruin porn,” Chamoiseau prefigures instead debates in contemporary heritage studies about the curation as opposed to the preservation of decay.12 The radical heritage practice he proposes is one of poetic intervention by photographers, sculptors and artists.

A quarter of a century on, the sites of the French Guianese penal colony have benefited from major heritage initiatives: the encroachment of nature into the bagne des annamites has been partially reversed and the site turned into a heritage-cum-leisure destination; the Transportation Camp at Saint-Laurent du Maroni has been significantly restored, with the process of ruination partially stabilized to create an impressive museum, documentation centre, and living exhibition space. Chamoiseau’s Memory Traces is a reminder that the conservation of such sites should reserve a place for creativity, for the imagination and for an openness to affective responses to the past. Such alternative forms of engagement, he argues, permit access to interstitial spaces, between the cracks of the ruin—it is from these that muffled, forgotten and otherwise marginalized voices will whisper back.

NOTES

1. On the global dimensions of penal colonies, see Clare Anderson (ed.), Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

2. For an overview of penal transportation in the French colonial empire, see Stephen A. Toth, Beyond Papillon: The French Overseas Penal Colonies 1854–1952 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

3. On the final years of the bagne, see Danielle Donet-Vincent, La Fin du bagne (Rennes: Éditions Ouest France, 1992). For Badinter’s intervention, see “Le bagne de Guyane: un crime contre l’humanité,” Le Monde, 24 November 2017.

4. See Andrew Stafford, “Patrick Chamoiseau and Rodolphe Hammadi in the penal colony. photo-text and memory-traces,” Postcolonial Studies, 11.1 (2008), 27–38.

5. See Peter Redfield, Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000).