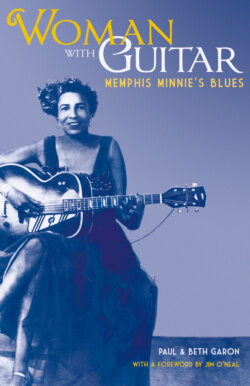

Читать книгу Woman with Guitar - Paul Garon - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеThe iconic status now accorded Memphis Minnie as a feminist symbol and female potentate in a man’s world is nothing new to the corps of devotees that had already developed by the time Woman with Guitar was first published in 1992. But she is far more widely recognized as a heroine now than when she was known mainly among hardcore blues collectors and among musicians and audiences who knew of her during her performing years. I would argue that much of this new adulation can be traced back to Woman with Guitar. While the number of people who actually read the book and took up her cause may have been only a few thousand, Paul and Beth Garon’s treatise became exponentially important to a more general readership and music-buying audience, especially as the digital age progressed. Woman with Guitar served as a source point for reviewers (of the book and of her CDs), for liner note writers of the many CD compilations that have since appeared, and ultimately for the half a million hits that a Google search for the name Memphis Minnie will now yield on the Internet. And the analytical discussions in the book have also opened more minds to probe what lies beneath the lyrics Minnie sang, to try to interpret and appreciate her songs (and indeed blues songs in general) in the contexts of creativity, imagination and poetic freedom. In the majesty and passion of her art, the blues could be a pathway to the heart or an incantation of desire. It could be a weapon in the war against race and gender prejudice, it could be a claim to free will. It could imbue the mundane with magic, it could conjoin the real with the surreal.

The same digital information network that has propelled awareness of Memphis Minnie’s music and her story from Woman with Guitar has also opened a window, limited as it may be—to print sources of the past that once seemed all but lost to us, to the world of Minnie’s heyday as a performer. When Woman with Guitar was first published, Google, amazon.com, allmusic.com, ancestry. com, Facebook and Youtube did not exist. Today ample material on blues is accessible through such Internet resources and books, specialist blues magazines, and newspaper archives.

Yet it is still true, as the authors note in chapter 1, that, considering Minnie’s significance in blues, “surprisingly little documentation exists for so extensive a career.” In a survey of vintage newspapers and magazines undertaken to contribute new material for this edition of Women with Guitar, I did find her records advertised in numerous periodicals, as well as club appearances publicized primarily in the Chicago Defender. But despite her obvious popularity as a recording artist and live entertainer, there was little coverage of Minnie as a personality, and no analysis of her songs beyond short record reviews. During her decades as an active performer, no newspaper or magazine even reported as much as her age, birth date or home town. Not even Langston Hughes, an obvious admirer who wrote an evocative Defender review of a Minnie performance, bothered to gather specific details of her life. Her first published biographies, brief but significant, appear to have been published in French, in Dictionnaire du Jazz by Hugues Panassié and Madeleine Gautier (1954)1 and in Big Bill Blues (1955) by Big Bill Broonzy and Yannick Bruynoghe, when Minnie’s career was nearing its end. Onah Spencer submitted a one-page typewritten bio on Minnie as part of the Illinois Writers Project Negro Music Survey, dated August 1, 1939, but this apparently was never published until now. (see WPA Interview in appendices).

While the lives, recordings and careers of blues artists both famous and obscure have been documented in obsessive detail over the past several decades, in Memphis Minnie’s day, blues artists weren’t accorded anywhere near this degree of biographical scrutiny. It was once rare to even see a photo or a news account of a black entertainer in the general daily press and popular magazines largely written by and for white communities. The class-conscious African American press promoted nationally successful black entertainers with a polished uptown image, such as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Fats Waller, Nat “King” Cole, Louis Jordan, Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots— not coincidentally the same acts, by and large, that came to enjoy some degree of crossover popularity with whites. Scant editorial coverage was allotted blues singers of the downhome southern or Chicago variety. But such papers were apparently happy to accept advertisements for records or club appearances by the likes of Minnie, Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Boy Williamson, Big Maceo and Tampa Red.

In Minnie’s case, the primary print outlet was the Chicago Defender. During the 1920s the Defender was loaded with ads for records by blues artists ranging from Bessie Smith and Ida Cox to Charley Patton and Blind Lemon Jefferson, often colorfully illustrated with drawings by white ad designers. Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe had the misfortune to begin recording just as the Depression was about to hit, resulting in a drastic cutback in record company advertising. So only a few of their records were advertised in the Defender (and some other black papers, including the New York Amsterdam News and the Baltimore Afro-American) in 1929–1930. After the Depression the record labels rarely advertised individual releases in newspapers any more, although record stores did often publish lists of the latest hits for sale in local papers. By the 1940s the national trade publication, Billboard, had become the major print medium for record label marketing (soon joined by Cash Box).

The Memphis Minnie records that were advertised in the Defender in the 1940s were listed along with numerous other releases in ads placed by record stores, usually mail-order houses based in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, or New York. What the Defender did print, from at least 1941 on, were ads for Minnie’s Chicago club appearances at the Cotton Club, Martin’s Corner, Frost’s Corner, Joe’s Rendezvous Lounge, and other nightspots, sometimes augmented by short news blurbs and occasional photos promoting her appearances (such items probably coming as part of the sales packages offered advertisers). The ads appeared in the paper’s local edition but the national edition carried occasional news.

News about Minnie was occasionally mentioned in other Defender reports, including her 1936 stint performing on an excursion boat, appearances in Columbus, Ohio, in 1937, and Ocala, Florida, in 1946, and a fete in her honor in Chicago in 1946.2

The Columbus report also noted “She hails from Chicago’s radioland”—a rare reference to an intriguing but so far little-documented phase of Minnie’s career when she was broadcasting live on the popular Red Hot and Low Down program (which aired on WCFL, WJJD and WAAF at various times from at least 1932 to 1938 and again on WCFL in 1941–42, according to radio logs from the Chicago Tribune. (These stations offered a variety of general-interest programming; black-oriented stations were still some years away at this point.) Red Hot and Low Down is also mentioned in Onah Spencer’s 1939 notes on Minnie. The regular host of Red Hot and Low Down was Bob Hawk, who later gained national fame hosting quiz shows on the CBS radio network.3 Information on blues artists who appeared on the program is spotty, but another may have been Kokomo Arnold, who was advertised as an “Internationally Famous Radio and Decca Recording Artist” in a July 9, 1938 Defender ad. (Minnie also later performed on KFFA in Helena, Arkansas, and WDIA in Memphis, according to Brewer Phillips. See p. 108.)

Minnie’s music was also featured in record reviews in the Defender and other papers, notably in “Rating the Records,” a column by the African-American poet and writer Frank Marshall Davis syndicated by the Associated Negro Press (ANP). Davis’s column, later headed “Keeping Up with the Discs,” also appeared in the Atlanta Daily World, Cleveland Call & Post, Baltimore Afro-American, Philadelphia Tribune, California Eagle, and other black newspapers. Davis reviewed a wide range of music, both black and white, and though blues may not have been his favorite genre, his knowledge of blues records seemed well grounded and he deemed blues important enough to include in regular fashion. He was reviewing Minnie’s records as early as the June 12, 1939, edition of the Daily World, praising Low Down Blues on Vocalion in a paragraph headed “Cellar Stuff” as “Another top-notch ‘race record’ … full of belly laughs.” In his August 21, 1941, column, printed in the Philadelphia Tribune, Davis wrote: “Memphis Minnie, who sings mean blues, gets her thumping rhythm going on the Okeh recording of Me and My Chauffeur Blues and Can’t Afford to Lose My Man. She shows good sense on the second side.” But in a November 1 piece in the Baltimore Afro-American he opined: “Memphis Minnie has done better than on her Okeh recording of In My Girlish Days and My Gage Is Going Up.”

Oddly enough, another singer who used the name Memphis Minnie—Minnie Wallace, who recorded for Victor on September 23, 1929, accompanied by members of the Memphis Jug Band, followed by sessions for Vocalion in 1935—proved more newsworthy, to some publications, for writing a song about a convicted murderer. Wallace penned “Trigger Slim Blues” about a Memphis gunman, James Goodlin, whose crimes had achieved recent notoriety. Jimmie Gordon recorded the song for Decca on June 4, 1940. Reporters for the Memphis Press-Scimitar and Delta Democrat-Times who talked to Wallace published more biographical information about her (a preacher’s daughter, in Port Gibson, Mississippi, and a resident of Greenville before moving to Memphis) than anyone did about our Memphis Minnie at the time.4 Neither paper noted the existence of a more famous Memphis Minnie; if they knew of her at all, they may have assumed she and Minnie Wallace (who recorded only under her own name, never as Memphis Minnie) were the same. The name Memphis Minnie, as a character in plays, actually preceded its appearance on Memphis Minnie’s records.)5

So it remained the tavern and the phonograph record that provided that the contexts for Minnie’s contemporary press coverage. The jukebox, a medium of both the tavern and the record, became the defining factor in Billboard’s approach to music. Whereas newspaper reviews were consumer-oriented, Billboard rated records in terms of their appeal to jukebox operators. And Minnie’s records were highly rated as likely to bring “coinage to the race locations.” She was even hailed as “the outstanding race blues singer of the day” in one review. Just to sample excerpts from a few reviews:

Me and My Chauffeur Blues/Can’t Afford to Lose My Man: “In the race register, the blues singing of Memphis Minnie always makes for coin machine magic at the Harlem spots.” (January 30, 1943)

Looking the World Over: “Operators servicing the out-and-out race business have a natural in Memphis Minnie’s Looking the World Over. The outstanding race singer of the day, Miss Minnie again impresses with her blues chant that tells how she sowed her wild oats, and now that she has had her fun is ready to settle down with her man.” (February 20, 1943)

I’m So Glad/Mean Mistreater Blues: “It’s top in race shouting that Memphis Minnie delivers, singing it way deep down and phrasing it blue as the guitar and string bass beat out a throbbing rhythmic accompaniment for her own selections.” (May 3, 1947)

Fish Man Blues: “An old hand at shouting out the backbiting race blues, Memphis Minnie stirs up plenty of excitement with her sultry and salty singing here. With a terrific rock to her chant, and the accompanying guitar, bass and drums pounding out a driving rhythm, gal spins out a blues classic for Fish Man Blues in which she tells her man to hold off his bait … Race spots will shower coin pieces on this platter, particularly for Fish Man Blues.” (September 13, 1947)

While Billboard’s reviews indicated sales potential for Minnie’s records, the discs never sold quite well enough for her to make the magazine’s charts for “race” or rhythm & blues records, which only began in October 1942 as the Harlem Hit Parade, leaving the earlier years of blues releases in uncharted territory.

In reconstructing blues history, researchers have relied heavily on the Defender and other black papers as well as Billboard when seeking what press coverage there was of blues artists. But with the advances in digitalization and microfilming, ads and record reviews have come to the light from a far-flung variety of daily and weekly local newspapers revealing that, while many readers may not have known Minnie’s music well if at all, a substantial general (primarily white) readership at least saw Minnie’s name in print.

In a series of ads that ran on the “Farm News” pages of a number of small weeklies in Texas and Oklahoma from August 1930 to May 1931, Brunswick branches in Dallas and Kansas City advertised more records by Minnie (on Vocalion) than by any other artist, black or white. Leroy Carr’s Vocalion discs were also regularly listed in the ads, which sometimes also advertised blues by Charley Jordan, Peetie Wheatstraw, Lee Green, Robert Wilkins, Lucille Bogan, Funny Paper Smith and others, along with gospel, pop, jazz and hillbilly releases and a picture of a Brunswick portable phonograph in every ad. These ads, in the Columbus (Texas) Colorado Citizen, the Hearne (Texas) Democrat, the Eufala (Oklahoma) Indian Journal and others, directed buyers simply to “Brunswick and Vocalion Dealers” and also solicited “Responsible Merchants” from areas where the company had no dealers.6

Advertising for records hit its lowest point during the remainder of the 1930s. But, with a boost from the wartime and early postwar economy, many music shops and other stores that carried records, including furniture dealers, jewelers, and department stores, actively advertised beginning in early 1945. Minnie’s Columbia releases were listed in store ads in such diverse periodicals as the Canton (Ohio) Repository, Naugatuck (Connecticut) Daily News, Council Bluffs (Iowa) Nonpareil, Las Cruces (New Mexico) Sun-News, Anniston (Alabama) Star and Charleston (West Virginia) Daily News. These stores listed a number of releases in each ad—pop, country, jazz and classical, with typically only a few blues, if any. Sometimes Minnie was the only blues artist listed in ads alongside Frank Sinatra, Perry Como and Harry James. The widespread coverage was evidence of Minnie’s status as a top Columbia artist and of the broad reach of Columbia’s major-label distribution. Columbia also included Minnie in ads promoting its roster in the entertainment trade magazine Variety in the 1940s.

Columbia and other labels also provided review copies to newspapers. While Billboard and the Associated Negro Press affiliates reviewed Minnie’s records most frequently, again her records occasionally popped up in the mainstream press, including some major outlets. Sometimes the releases were merely listed but some reviewers also offered opinions. The Chicago Tribune, no less, noted Cherry Ball and I Don’t Want No Woman I Have to Give My Money To by Kansas Joe & Memphis Minnie on November 30, 1930, along with other Vocalion and Brunswick records by Robert Wilkins, Joe Callicott and Lee Green.7 On November 14, 1935, the San Antonio Light recognized her Joe Louis Strut as an example of recent songs with topical themes.8 Minnie made the Tribune again on March 25, 1945, when critic Will Davidson enthused, “There is an art to appreciating good blues singing, but how can you miss the strange appeal of Minnie in When You Love Me or Love Come and Go?”9 Columbia evidently put extra promotional push behind this Okeh single as part of its first batch of releases upon the lifting of a record ban imposed by the American Federation of Musicians in 1942.10 It was also reviewed in the New York Herald Tribune (by music critic Paul Bowles, a noted novelist and composer), Times-Picayune, New Orleans States, Cleveland Plain Dealer and Greensboro Daily News.11

A scattering of ads and news items from 1946 help track Minnie’s touring that year, perhaps booked by Ferguson Brothers of Indianapolis, a leading agency in the representation of black entertainers of the era. Her appearance in Ocala, Florida, on June 8, was publicized in the black press, including the Defender and Pittsburgh Courier, while other ads appeared in local daily newspapers including the Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, Kokomo (Indiana) Tribune and Danville (Virginia) Bee for concerts in those cities.12 In several ads, in Chicago and on tour dates, the billing was to “Memphis Minnie and Her Electric Guitar,” her amplified instrument already having been documented as a strong element of her live shows by Langston Hughes’s Defender review of her show at the 230 Club. An October 7, 1944, Martin’s Corner Defender ad touted her as “Master of Electric Guitar.” It raises the question of how much more powerful her live performance sound may have been than on her studio recordings; likewise, several 1946 tour dates advertised her with Leo Hines’s fourteen-piece orchestra, a configuration that was never captured in her recording sessions. Occasional ads and articles prove, or sometimes at least suggest, that she was also performing for white or mixed audiences, presumably on the excursion steamer mentioned in the Defender in 1936, at black and tan clubs, on her 1946 concert tour where separate white seating was advertised in Virginia, and at Schindler’s Theatre in Chicago in 1951, where she was advertised in the December 22 Defender as “Queen of the Blues.” A Chicago Tribune notice of November 9, 1952, indicates that the folk music movement was attuned to her music as well, as she took Big Bill Broonzy’s place at a “Come for to Sing” program at the Blue Note.

During her post-Columbia career Minnie’s presence in the press declined, although Billboard did continue to cover her releases on Regal, Checker and J.O.B., and her Chicago appearances were still advertised for a few years in the Defender. Just as her star was waning with the black American blues audience, European blues enthusiasts began writing about her. Georges Adins from Belgium corresponded with her prior to visiting her in Memphis in 1962, resulting in a 1963 article in R and B Panorama. He, along with Big Bill Broonzy and Yannick Bruynoghe, may have supplied Hugues Panassié with information for the Memphis Minnie entry in Dictionnaire du Jazz in 1954. Adins’s article and a Mike Leadbitter piece in the British journal Blues Unlimited provided much of the framework for Minnie’s biography as we know it.

In the United States, jazz critic Leonard Feather, a British transplant, included a short entry on Minnie in the New Edition of the Encyclopedia of Jazz in 1960 (after omitting her from the first edition) but it seems entirely based on Broonzy’s book. Following Minnie’s stroke and retirement there was little written about her in the American press in the 1960s, although on May 25, 1968, her hometown Memphis Commercial Appeal reported on a gathering organized in her honor by local aficionado Harry Godwin at the nursing home where Minnie resided (see p. 139).

This sampling of Memphis Minnie in the press represents only what a few blues researchers have found over the years along with recent results of digital searches of newspaper archives on genealogy web sites. Undoubtedly as more and more newspapers are microfilmed and digitized, there will be more to discover about Memphis Minnie and her music. But with what we already know we can better appreciate the broader national scope of her fame and her importance, and the special appeal of a remarkable “Woman with Guitar.”

—Jim O’Neal, January 2014

(Thanks to Rob Ford, Robert Pruter, Scott Dirks and Frank Hoffman’s Jazz Advertised in the Negro Press for information on articles and ads, and to Elin Peltz for Library of Congress copyright research. Thanks also to Vicente P. Zumel for research assistance.)