Читать книгу Of Gardens - Paula Deitz - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

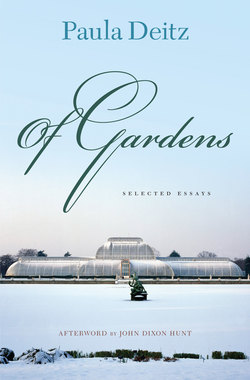

ОглавлениеA Bouquet of British Parks: Liverpool, Edinburgh, and London

THE SLANT of late afternoon sun enhanced the spring green of New York's Central Park as I walked home along its winding paths and around the still, dark waters of the reservoir. Although I had walked this route hundreds of times over the years, the experience was enriched by having recently walked in the public park in England that gave Frederick Law Olmsted, Central Park's creator, the idea in the first place.

Writing in 1852, Olmsted described taking a ferry from Liverpool to Birkenhead on a spring day. He stopped to eat some buns in a baker's shop, and it was the baker “who begged of us not to leave Birkenhead without seeing their new park.” Olmsted proceeded to the entrance, an impressive stone archway with Ionic columns (it still exists) and into a “luxuriant and diversified garden” with “winding paths,” “varying surfaces” planted with shrubs and flowers, and “a greensward, closely mown,” where gentlemen were playing cricket.

In general, Britain's public parks and gardens stem from two traditions. One is the conversion to public use of royal hunting preserves and gardens, frequently known as the Royal Parks. The other is the creation by city governments, mostly in the nineteenth century, of recreational parks and open spaces to improve the health of those who lived in congested urban slums.

There is no one season to visit parks, for they are like museums with changing exhibitions; each season has its own particular charm, color, and fragrance. But if you walk in parks at home to feel a respite from the pulse of the city, you will love them in Britain, as I did during a week's visit to public parks in London, Liverpool, and Edinburgh.

Liverpool

I began with Liverpool, at the park that inspired Olmsted, now known as Birkenhead Park. It was laid out from 1844 to 1846 by Sir Joseph Paxton, architect of the Crystal Palace in 1851 and head gardener to the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth in Derbyshire. Strolling through it, one has a sense of déjà vu, with its hilly contours of land, random arrangement of trees, and outer circular park drive ringed with villas. Swans glide across a pond lined with willows. Outside the Birkenhead Park Cricket Club, a Victorian chaletstyle pavilion, spectators on green benches watched one of the last matches of that season.

From Birkenhead Park, one crosses the Mersey River to Liverpool's newest park, Riverside. It was created as part of last year's International Garden Festival and includes a splendid esplanade, punctuated by lampposts, stretching out along the estuary.

Riverside was built over a garbage dump and oil tanks. In only two years, landscapers have shaped an undulating terrain with distant views across the Mersey to the Welsh hills on the south. It will be years before the oak and beech trees are mature, but the outlines are there—rivulets cascading into an oxbow lake and embankments of wildflowers. Among the features that remain in the 125-acre area are the new Festival Hall and the excellent garden paths created by the Japanese. The festival's international theme gardens, inside the park, were so successful that they will be open again this year.