Читать книгу Of Gardens - Paula Deitz - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIN 1625, the British philosopher and empiricist Francis Bacon wrote in his seminal essay “Of Gardens” that without gardens “buildings and palaces are but gross handiworks,” and that even “when ages grow to civility and elegancy, men come to build stately sooner than to garden finely; as if gardening were the greater perfection.” As I reread this passage recently, my mind harkened back to the experience that jolted me into understanding landscape architecture, not just as a stepsister to architecture, as Bacon partially implies, but as the means by which man redeems the natural environment through design. The occasion was a lecture by the landscape architect and ecologist Ian L. McHarg at Rockefeller University in New York City. He had just published his book Design with Nature, and that evening, along with his clarion call for environmental responsibility, he coined the concept of “the reassuring landscape,” defined as cherished scenes from childhood that we continually seek out or recreate later in life. This lecture struck a chord in me and eventually became the taproot of this book. McHarg was a founder of the Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania, and therefore it is a singular privilege for me that John Dixon Hunt, Professor of the History and Theory of Landscape Architecture in that department, selected this collection for the Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture, of which he is the inaugural series editor.

Three years after McHarg's lecture, the Whitney Museum of American Art presented the exhibition “Frederick Law Olmsted's New York.” At the entrance to this show was a map of the United States with Olmsted's landscape designs pinpointed across it. Standing there I realized that my entire young life, with the exception of my college junior year abroad in Geneva, Switzerland, had been circumscribed by Olmsted's pastoral landscapes. I was raised in Trenton, New Jersey, where Cadwalader Park, with its bucolic hills and dales, was the focus of recreational and cultural events (sledding the best of all), followed by Smith College, where Olmsted designed the entire campus as a botanic garden and arboretum, with every tree and plant labeled. And finally, I settled in New York City, where I live two blocks from Central Park and walk its paths regularly. The American landscape, as I knew it, was derived from the eighteenth-century picturesque parks and gardens Olmsted had visited in England and recreated on native soil.

During the six weeks that the Smith College Geneva group spent in Paris my year, before the term began at the University of Geneva, Versailles topped the list of our orientation activities. I still have the class photograph documenting the unforgettable visit that gave us our first view of André Le Nôtre's gardens. Until then, nothing in my life had prepared me for the classical grandeur and geometric precision of those seemingly endless parterres, bosquets, fountains, and statuary set among topiary and clipped trees. Like Ian McHarg in his book, I was enthralled with the snow-capped Alpine scenery of Switzerland during the subsequent year as well as with the local farm villages, wildflower fields in spring, and vineyards cascading down mountains. But the rigorous beauty of Le Nôtre's designs became the lasting touchstone for me, linking gardens with history as well as nature. What had prepared me to understand this linkage was a lecture in European intellectual history at Smith presented during the preceding year by Elisabeth Koffka. She gave an account of the bridge between the Enlightenment and Romanticism, which has stayed with me ever since when thinking and writing about Western gardens, where, reflecting the evolution of literary and artistic movements, the earlier classicism of gardens evolved into the Romantic landscape park. Madame Koffka, as she was always called, was also our faculty adviser during the Geneva year, which gave us the constant benefit of her insights and perceptions.

Many years later, when I married Frederick Morgan, I began to spend my summers at his house on the coast of Maine. During my first week there, the local postmistress took me under her wing and gave me a list of places to visit in the area, including the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden in Seal Harbor, on the nearby island of Mount Desert. She explained that the garden was open to the public one day a week. I have visited this garden every summer since, and no matter how familiar it became, the first impression of passing through the gate in the Chinese wall, through the dark woods, and into the walled garden with its three concentric rectangles of brilliant flower borders remained as startling as ever. On that initial visit, I remember thinking, “This is landscape architecture”—a garden whose plan was as intricately conceived as any major structure. It was the first of many landscapes I was to visit over the years designed by Beatrix Farrand. This was the garden that inspired me to write about landscape.

I cite these formative experiences with Olmsted, Le Nôtre, and Farrand because I realized, as I edited these essays, that references to their work recur throughout, for they figure prominently in the lives and work of many of the landscape architects and designers about whom I have written. Even the most contemporary among them draw inspiration from the basic concepts of Olmsted, Le Nôtre, and Farrand, so one might say that these three have spurred dynasties, with each generation adding a fresh interpretation.

By the time I saw the Rockefeller Garden, I already knew the campuses of Princeton and Yale universities well but did not know they incorporated designs by Beatrix Farrand. Her other major extant garden was Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., where in May 1980 its Center for Studies in Landscape Architecture sponsored a symposium titled “Beatrix Jones Farrand (1872-1959): Fifty Years of American Landscape Architecture.” The surrounding Georgetown streets lined with charming Federal houses were blanketed with wisteria vines and pink dogwood that spring weekend, and yet we all sat in a dark auditorium for two days of lectures with intermittent walks in the garden and lunch in the Orangery. For me, the weekend was a turning point because it was my first foray into what we call “the garden world,” where I met writers, designers, and scholars, many of whom have remained good friends ever since. I have always been struck by the generosity of members of this garden world even as the circle expanded with other such occasions over the years both here and abroad. I wrote about the Dumbarton Oaks event for the New York Times, and my career as a garden writer was launched.

While studying for my master of arts in French literature at Columbia University, I was naturally under pressure to proceed to a doctoral degree. But I decided instead that were I ever to write at length, I would do so for millions of people who would read my work riding the subway without knowing who I was. My wish came true when I began writing for the New York Times, where almost half of the pieces reprinted here first appeared. Only one, “1680 Formal Garden Discovered in the South,” made the front page, on December 26, 1985; it was a story about a remarkable archeological discovery that shifted our views of Colonial gardens. At a dinner party the following week, the gentleman on my right recounted the entire story back to me chapter and verse, thinking it would interest me, though he had no idea that I had written it. I had achieved my goal. In the end, I received my doctorate anyway, albeit an honorary one in humane letters from Smith College with a citation, for which I was deeply grateful, noting that my published works on landscape design “help readers from all walks of life appreciate the historical and contemporary dimensions of our physical environment.” In lieu of a thesis, I offer this book.

Many of the connections among these essays are obvious, for one feature led directly to another as I traveled across America and in countries abroad, especially Great Britain, France, and Japan. But other connections were not obvious to me until the writing stage when I would discover while preparing a piece about the New York Botanical Garden, for example, that Nathaniel Lord Britton, the garden's first director, wrote a book in 1918 titled Flora of Bermuda that has served in recent years as the main resource for replanting native species on an island off Bermuda, the subject of another article. Or, in writing about the Désert de Retz in France and Painshill Park in England, eighteenth-century folly gardens, I found that Thomas Jefferson visited them both in the same year, 1786, when he was minister to France.

This book records a great adventure of continual discovery, not only of the artful beauty of individual gardens and landscapes but also of the intellectual and historical threads that weave them into patterns of civilization, from the modest garden for family subsistence to major urban developments. Landscapes, ever changing and ephemeral, are an expression of our ways of taming the environment, mindful of its fragility now as we address ecological issues of sustainability. These essays, then, are also about people over many centuries and in many lands who have expressed their originality and individuality by devoting themselves to cultivation and conservation. My aim as a writer and observer has been to report accurately my descriptions and knowledge of these places so that the reader can share the experience.

A few years ago, on a winter afternoon, I made one of many return visits to Versailles, this time to view an exhibition of royal porcelain and table settings. In keeping with the nature of the show, a café was set up in one of the boiserie-encrusted salons overlooking the garden. While I sipped my tea and ate my chocolate patisserie listening to seventeenth-century music, I had an extraordinary sensation of what it actually felt like to live at Versailles. As I gazed out the window, it began to snow, with great swirls lifted by a fierce wind. It was already dusk, but I hastened to finish and went out into the garden. Because the wind came from only one direction, all the immense pyramidal topiaries were only half covered in snow. I bundled up and walked down the long avenue as far as the Fountain of Apollo when I suddenly realized that I was completely alone in the garden, and that it was now dark. Before I panicked that the gates might be closed, I was exhilarated by the awareness that, like Louis XIV, I had the garden to myself. I realized then that because gardens give structure without confinement, they encourage a liberation of movement and thought, a legacy over time and from many cultures that accounts for Francis Bacon's conclusion “nothing to the true pleasure of a garden.”

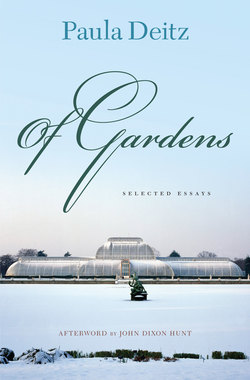

Facing page: Eugène Atget, Versailles, coin de parc, 1902.