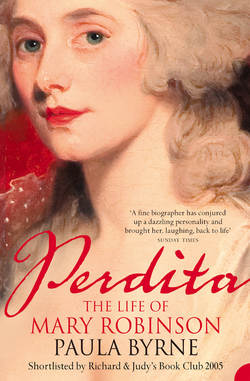

Читать книгу Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson - Paula Byrne - Страница 12

CHAPTER 5 Debtors’ Prison

Оглавление‘Tis not the whip, the dungeon, or the chain that constitutes the slave; freedom lives in the mind, warms the intellectual soul, lifts it above the reach of human power, and renders it triumphant over sublunary evil.

Mary Robinson, Angelina

News had reached Tregunter of Robinson’s imminent arrest. Harris was away from home when they arrived, but on his return he lost no time in making his position clear: ‘Well! So you have escaped from a prison, and now you are come here to do penance for your follies?’1 Over the following days, he taunted the couple, though he did at least offer them refuge.

When Mary tried to amuse herself by playing an old spinet in one of the parlours, Harris mocked her for giving herself airs and graces: ‘Tom had better married a good tradesman’s daughter than the child of a ruined merchant who was not capable of earning a living.’ She may have smarted from the insults, but her husband, knowing her temper, pleaded with her to ignore Harris’s behaviour. She was furious, though, when he openly insulted her at a dinner party. A guest, remarking on her swollen stomach, expressed his pleasure that she was come to give Tregunter ‘a little stranger’ and joked (as Harris was renovating his house) that they should build a new nursery for the baby. ‘No, no,’ replied Mr Harris, laughing, ‘they came here because prison doors were open to receive them.’2

The renovation of Tregunter meant that Mary could not be housed for her confinement – at least that was the excuse given by Harris. Only two weeks away from giving birth, Mary was told that she must go to Trevecca House, which was just under two miles away, at the foot of a mountain called Sugar Loaf. Away from Harris and his female cronies, she relaxed and communed with nature:

Here I enjoyed the sweet repose of solitude: here I wandered about woods entangled by the wild luxuriance of nature, or roved upon the mountain’s side, while the blue vapours floated round its summit. O, God of Nature! Sovereign of the universe of wonders! in those interesting moments how fervently did I adore thee!3

The sentiments are typical of the age of sensibility. If she really wandered thus so late in her pregnancy, she must have been unusually healthy and energetic.

Though Mary writes here of the ‘sweet repose of solitude’, Trevecca House was actually more crowded than Tregunter. One part housed the Huntingdon seminary and another part of the building was converted into a flannel manufactory. Nevertheless, she was no longer forced to endure the jibes of her husband’s vulgar family, for they seldom visited her. According to the Memoirs, she was indifferent to their ill-treatment of her. Her spiritual communion with the mountains made her all the more conscious that she had ‘formed an union with a family who had neither sentiment nor sensibility’.

The child, named Maria Elizabeth Robinson,* was born on 18 October 1774, just a few weeks before Mary’s seventeenth birthday. Delighted with her beautiful daughter, the young mother allowed her nurse to show Maria Elizabeth to the factory workers who clamoured to see the ‘little heiress to Tregunter’. Mary was at first alarmed at the prospect of exposing the baby to the cold October air, but the nurse soothed her fears and cautioned her that the local people would consider Mary ‘proud’ if she refused to show the ‘young squire’s’ baby. It was a happy day for Mary, as the crowd heaped blessings on the baby, and the nurse, Mrs Jones, passed on every detail of their praises to the exhausted mother.

There is no mention of Robinson in the narrative, but later that evening Harris paid a visit. After asking after Mary’s health he demanded to know what she was going to do with the child. When she made no answer he honoured her with his own recommendation: ‘“I will tell you,” added he; “Tie it to your back and work for it.’” For good measure he added, ‘Prison doors are open … Tom will die in a gaol; and what is to become of you?’ Mary was all the more humiliated by the impropriety of these taunts being spoken in front of the nurse. Maybe Harris would have been kinder if the baby had been a boy, but one senses that his own infatuation with Mary had now worn off and that he considered her expensive lifestyle to have been a major factor in Tom’s improvidence. When his daughter Elizabeth made her visit, she suggested that it would be a mercy for the infant ‘if it pleased God to take it’.4

Three weeks later, Robinson’s creditors caught up with him. They had discovered that he had fled to Wales, and in order to avoid the spectacle of being arrested at Harris’s house – which would have been the final nail in the coffin of his hoped-for inheritance – he left immediately. They were on the run once more. Though still weak from the delivery of her child, Mary refused to stay at Trevecca without her husband. She travelled against the advice of the capable Mrs Jones. They set off for Monmouth, where Mary’s grandmother lived. Mrs Jones travelled in the post chaise as far as Abergavenny, cradling the baby on a pillow on her lap. The local people were sorry to see them go, but ‘Neither Mr Harris nor the enlightened females of Tregunter expressed the smallest regret, or solicitude on the occasion.’5

Mary was worried about taking care of her baby after the departure of Mrs Jones. Her education had not prepared her for ‘domestic occupations’. She was still only 17, and without her mother. But she trusted her maternal instincts and did the best she could. Lacking a wet nurse, she breastfed her own baby, which was still perceived as an unusual step for a woman of her class – though it was something that would be advocated by the feminist writers of the 1790s.

The next day they arrived at Monmouth, where Mary’s grandmother Elizabeth lived. They received a warm welcome, though how much her grandmother knew about their state of affairs is not clear. Seventy-year-old Elizabeth, who had been a beauty in her day, was still an attractive woman; she dressed in neat, simple gowns of brown or black silk. She was a pious, well-respected figure, and mild of temper: Mary envied her grandmother’s tranquillity and her fervent religious faith.

Here at Monmouth they received ‘unfeigned hospitality’. There was a lively social scene. Once more Mary’s contradictory nature is revealed. Her favourite amusements were wandering by the River Wye and exploring the castle ruins: thus the woman of sensibility who would become one of the most successful Gothic novelists of the age. But she also loved company and attended local balls and dances: thus the lady of fashion who would become a fixture on the London social scene.

Determined not to let breastfeeding interfere with the chance to dance at a local ball, she once took Maria Elizabeth with her, so that she could feed her at intervals. After a particularly strenuous bout of dancing, she fed her in an antechamber. But something went wrong and by the time they arrived home the baby was in convulsions. Mary was hysterical, with the result that her milk would not then come at all, which left the baby parched and continuing to fit. Mary was convinced that her vigorous dancing and the excessive heat of the ballroom had affected her milk and brought on the fit. She stayed awake with Maria Elizabeth all night. In the morning, friends and well-wishers called to enquire after the infant. One such man was the local clergyman, who was moved to see the frantic young mother in such despair. Mary refused to let the baby be taken from her lap, but the clergyman begged her to let him try a home remedy that had been successful with one of his own children suffering the same way. Mixing aniseed with spermaceti, he gave the medicine to the baby and almost instantaneously the convulsions abated and she fell peacefully asleep.

Shortly after this episode, Tom Robinson once more heard that his creditors were about to catch up with him. Yet again, they prepared to travel before Robinson was arrested. But this time they were too late. An execution for a ‘considerable sum’ was served on him and the local sheriff of Monmouth arrived to arrest him. In the event, the sheriff, who knew Mary’s grandmother, took pity on them and offered to accompany the Robinsons back to London.

On returning to the metropolis, Mary hastened to her mother, who was now living in York Buildings just off the Strand. Hester was, of course, thrilled to see her new granddaughter. Robinson, in the meantime, discovered that the person responsible for alerting the sheriff was none other than his best friend Hanway. The latter’s excuse was that the debt in question was relatively small and he had assumed that Robinson’s father would have paid it. They came to an arrangement and patched up their friendship. The Robinsons then took lodgings in Berners Street, just north of Oxford Street.

Mary began to make arrangements to fulfil a secret ambition that she had been harbouring for many years. She now had ready for publication her first book of poems: she had been working on them even before her marriage. In her Memoirs, she spoke disparagingly of her first literary efforts as ‘trifles’; she expressed the hope that no copies survived, except for the treasured one that her mother had preserved. Regardless of the quality, her determination in preparing the volume in such difficult circumstances is impressive. She was also unusual among upwardly mobile women in undertaking the everyday care of her own baby. She insisted on dressing and undressing her daughter. The baby was breastfed and always slept in her presence, by day in a basket, by night in her own bed. Mary had heard horror stories about the neglect of servants towards children who were too young to tell tales, and she resolved only to let herself and Hester tend to the child.

Her devotion as a mother and her plans to become a published poet did not stop her from socializing, and she began visiting her old haunts such as Ranelagh with her female friends, while Tom kept a low profile. Mary had renewed confidence in her personal appearance and her deportment. She had grown taller in the last year and felt more worldly and sophisticated than when she had first broken upon the social scene two years earlier. She felt confident, serene, and was a little harder edged. The special occasion of her reappearance in London society is marked in her Memoirs by a description of a new dress. This one was of lilac silk with a wreath of white flowers for a headdress. ‘I was complimented on my looks by the whole party,’ she recalled, before stressing that her first concern was to be a good mother: ‘with little relish for public amusements, and a heart throbbing with domestic solicitude, I accompanied the party to Ranelagh’.6

As she entered the rotunda the first person she encountered was her old ‘seducer’ George Fitzgerald. He was startled to see her, but lost no time in greeting her, welcoming her re-entry into ‘the world’ and observing that she was without Robinson. He followed her for the remainder of the evening, and as she left she observed his carriage drawing up alongside hers. The next morning he arrived at the house to pay his respects, as she sat correcting proofs of her poetry, with her daughter sleeping in a basket at her feet. She was annoyed at the intrusion and her vanity was piqued by the fact that she was dressed in a matronly morning dress rather than ‘elegant and tasteful dishabille’. Papers were strewn over the table, making the room look like a cross between ‘a study and a nursery’.

She received him frostily. Undeterred, Fitzgerald complimented her on her youth and her child on her beauty. The attention to Maria Elizabeth led to a thaw. Fitzgerald then took a proof sheet from the table and read one of the pastoral lyrics, praising her efforts. ‘I smile while I recollect how far the effrontery of flattery has power to belie the judgment,’ Mary wryly notes in her Memoirs.7 She asked him how he had discovered her place of residence and Fitzgerald confessed that he had followed her carriage from Ranelagh the previous evening.

The next evening he returned and took tea with the Robinsons, inviting them to a dinner party at Richmond. Mary declined, but she and Tom tentatively began to socialize with their old friends. Returning to Ranelagh a few days later they reacquainted themselves with Lord Northington, Captain O’Byrne, Captain Ayscough, and the wicked Lord Lyttelton, who had not changed one bit and was – as only to be expected – ‘particularly importunate’.

For a few weeks it looked as if the Robinsons were embarking on their old life again, but then Tom was arrested on a debt of £1,200, consisting principally of ‘the arrears of annuities, and other demands from Jew creditors’. Mary insisted that the debts were all his own: ‘he did not at that time, or at any period since, owe fifty pounds for me, or to any tradesman on my account whatever’.8 Robinson stayed in custody in the sheriff’s office for three weeks. He felt too depressed even to go through the motions of trying to raise the money from his father or his friends. Prison was inevitable and he was duly committed to the Fleet on 3 May 1775. He would spend the next fifteen months there.

The Fleet housed about three hundred prisoners and their families. It was a profit-making enterprise: prisoners had to pay for food and lodging, pay the turnkey to let their families in and out, and even pay not to be kept shackled in irons. There were opportunities for work, though some inmates were reduced to begging from passers-by – a grille was built into the prison wall along Farringdon Street for this purpose.

It was not a requirement, but was nevertheless common, for wives to accompany their husbands to debtors’ prisons such as the Fleet, the Marshalsea and the King’s Bench. Mary did so – as her fellow novelist and poet Charlotte Smith would when her husband was confined a few years later. Often wives would come and go, bringing in for their confined husband. Young children were, however, usually left with relatives. It is a mark of Mary’s deep devotion to her baby that she took the 6-month-old Maria Elizabeth to prison with her rather than leaving her in the care of Hester. For that matter, she could presumably have stayed with Hester herself. Her loyalty to Tom Robinson is striking, especially in the light of his infidelities.

They were given quarters on the third floor of the towering prison block, overlooking the racquet ground, which the inmates were at leisure to use for exercise. Robinson – an ‘expert in all exercises of strength’ – played racquets daily while Mary tried her best to make a home in the squalid surroundings, and took care of her baby. She barely ventured outdoors during daylight hours for a period of nine months, though she did at least have a nurse to help her with the baby. The cells were small, dark, and sparsely furnished, but at least they were given a pair of rooms and not just one. This meant, however, that they paid extra for lodging, which meant that it would take longer to put aside the money to pay off the debt.

According to the memoirs of Laetitia Hawkins, a neighbour of Mary’s during her years of fame, Robinson was sent a guinea a week subsistence money by his father. He was also offered some employment ‘in writing’ – probably the copying of legal documents, an activity for which he was well trained – but he refused to do anything. Mary, by contrast, not only attended to her child but also ‘did all the work of their apartments, she even scoured the stairs, and accepted the writing and the pay which he had refused’.9

Less welcome offers of assistance came from the rakish lords, Northington, Lyttelton, and Fitzgerald. She knew, though, from the ‘language of gallantry’ and ‘profusions of love’ in their letters what the offers really meant. It was above all her maternal devotion that kept her from exchanging a life of poverty for the temporary comforts afforded to a courtesan.

At night, she would walk on the racquet court. One beautiful moonlit evening, she went out with her baby and the nursemaid. Mary would later remember it as the night when her daughter ‘first blessed my ears with the articulation of words’. They danced the child up and down, her eyes fixed on the moon, ‘to which she pointed with her small fore-finger’, whereupon a cloud suddenly passed over it and it disappeared. Little Maria Elizabeth dropped her hand slowly and, with what her mother perceived as a sigh, cried out ‘all gone’. These were her first words – a repetition of the phrase used by her nurse when she wanted to withhold something from the baby. In retrospect, it seemed like the one joyful moment in the long months of captivity. They walked until midnight, watching the moon play hide and seek with the clouds as the ‘little prattler repeated her observation’.10

Twenty years later, Mary’s friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge would make one of his loveliest poems out of a similar experience. Coleridge writes of how his infant son Hartley could recognize the song of the nightingale before he could talk:

My dear babe,

Who, capable of no articulate sound,

Mars all things with his imitative lisp,

How he would place his hand beside his ear,

His little hand, the small forefinger up,

And bid us listen!

He then tells of how one night when baby Hartley awoke ‘in most distressful mood’, he scooped him up and hurried out into the orchard

And he beheld the moon, and, hushed at once,

Suspends his sobs, and laughs most silently,

While his fair eyes, that swam with undropped tears,

Did glitter in the yellow moon-beam.11

Coleridge’s poem was written in April 1798, two years before Mary drafted this section of her Memoirs. It was published in Lyrical Ballads, a book she knew well (it would inspire the title of her final volume of poetry, Lyrical Tales). What is more, Coleridge visited her on several occasions in the early months of 1800, when she was writing the Memoirs. They subsequently wrote poems inspired by each other’s work. There can, then, be little doubt that the phrasing of her memory of Maria Elizabeth by moonlight – the idea of ‘articulation’, the baby’s raised forefinger, the dancing yellow light – was shaped by a memory of Coleridge’s poem for Hartley. Later in 1800, she paid a further compliment in the form of a lovely poem for Coleridge’s third son, Derwent.

It was only as a result of the literary revolution of the 1790s, in which Coleridge and Robinson each played an important part, that intimate memories of this kind became the stuff of poetry and autobiography. Mary’s early verse, published while she was in the Fleet, was stilted and artificial in comparison. Poems by Mrs Robinson, an octavo volume of 134 pages, was published in the summer of 1775, with a frontispiece engraved by Angelo Albanesi, a fellow prisoner who had been befriended by Tom. The volume garnered a mediocre notice in the Monthly Review: ‘Though Mrs Robinson is by no means an Aiken or a More, she sometimes expresses herself decently enough on her subject’ (Anna Aikin and Hannah More were the most admired ‘bluestocking’ poets of the age).12

The volume includes thirty-two ballads, odes, elegies, and epistles. For the most part, they consist of pastorals (‘Ye Shepherds who sport on the plain, / Drop a tear at my sorrowful tale’) and moral effusions (pious outbursts addressed to Wisdom, Charity, Virtue, and so forth) that are typical of later eighteenth-century poetry at its most routine. But a handful of the poems show signs of future promise: there are, for instance, some brief character sketches in which one may see the seeds of the future novelist’s voice.

Several of the poems were modelled on the work of Anna Aikin (later Barbauld): ‘The Linnet’s Petition’, for example, was an imitation of her ‘The Mouse’s Petition’. Women’s poetry of the period was often written in the form of verse letters. Mary’s ‘Epistle to a Friend’ is written with a lightness of touch and warmth of feeling:

Permit me dearest girl to send

The warmest wishes of a friend

Who scorns deceit, or art,

Who dedicates her verse to you,

And every praise so much your due,

Flows genuine from her heart.13

One is left wondering about the identity of the friend, especially as the following poem is an elegy ‘On the Death of a Friend’, which ends ‘May you be number’d with the pure and blest, / And Emma’s spirit be Maria’s guard.’ We know hardly anything about Mary’s female companionship of these early years, beyond a passing reference in the Memoirs to her close friendship with a talented, witty, and literary-minded woman called Catherine Parry. In Mary’s last years, by contrast, she was sustained by a large circle of intellectually accomplished women. The only one of these early poems with a clearly identifiable biographical subject is an elegy on the death of the ‘generous’ Lord Lyttelton, whose poems were among the first that Mary loved. Needless to say, it makes no mention of the younger Lord Lyttelton.

The one poem in the collection that has real merit, and that deserves to be anthologized, is a ‘Letter to a Friend on leaving Town’. The virtue of a simple country life as against the vice of indulgence in the city was a common poetic theme in the period, but here there is a real sense of Mary writing from experience:

Gladly I leave the town, and all its care,

For sweet retirement, and fresh wholsome air,

Leave op’ra, park, the masquerade, and play,

In solitary groves to pass the day.

Adieu, gay throng, luxurious vain parade,

Sweet peace invites me to the rural shade,

No more the Mall, can captivate my heart,

No more can Ranelagh, one joy impart.

Without regret I leave the splendid ball,

And the inchanting shades of gay Vauxhall,

Far from the giddy circle now I fly,

Such joys no more, can please my sicken’d eye.

Although Mary adopts the conventional pose of condemning fashionable London life, all her poetic energy belongs to that life – her heart is still captivated by Ranelagh and Vauxhall. Yet she also has the maturity to see their dangers. At the centre of the poem is a telling portrait of the society belle who loses her looks, and thus the interest of the gentlemen of fashion, but remains addicted to the treadmill of the social calendar:

Beaux without number, daily round her swarm,

And each with fulsome flatt’ry try’s to charm.

Till, like the rose, which blooms but for an hour,

Her face grown common, loses all its power.

Each idle coxcomb leaves the wretched fair,

Alone to languish, and alone despair,

To cards, and dice, the slighted maiden flies,

And every fashionable vice apply’s,

Scandal and coffee, pass the morn away,

At night a rout, an opera, or a play;

Thus glide their life, partly through inclination,

Yet more, because it is the reigning fashion.

Thus giddy pleasures they alone pursue,

Merely because, they’ve nothing else to do;

Whatever can afford their hearts delight,

No matter if the thing be wrong, or right;

They will pursue it, tho’ they be undone,

They see their ruin, – yet still they venture on.14

This poem – an accomplished piece of work for a 17-year-old girl – was almost certainly written when Mary was moving in the fashionable circles of London society. It is at one level an anxious imagining of her own future fate. But seeing it in print, she must have wished she was back gliding her life away in the world of ‘scandal and coffee’ rather than languishing in the Fleet surrounded by women whose good looks had been worn down by penury.

Mary knew that her own beauty was fragile. She wrote in the Memoirs of how during her ‘captivity’ in prison her health was ‘considerably impaired’. She declined, however, to ‘enter into a tedious detail of vulgar sorrows, of vulgar scenes’.15 At this point in the original manuscript of the Memoirs several lines are heavily crossed out. It is impossible to decipher the words beneath the inking over, but there just might be a reference to pregnancy. It is therefore striking that the malicious but well-informed John King wrote in his Letters from Perdita to a Certain Israelite: ‘the Husband took refuge in the Fleet, immured within whose gloomy Walls they pined out Fifteen Months in Abstemiousness and Contrition, where her constrained Constancy gave birth to a Female Babe, distorted and crippled from the tight contracted fantastic Dress of her conceited Mother’.16 Since ‘Fifteen Months’ is an exactly correct detail, we cannot immediately dismiss King’s other piece of information about this period: his startling claim that Mary had a baby while in prison. ‘Distorted and crippled’ is certainly not a description of the lovely little Maria Elizabeth. Could it then be that the deleted passage in the Memoirs referred to a miscarriage or an infant death?

Imprisonment for debt was known as ‘captivity’, and this gave Mary the title for a new poem, much her longest work to date. Written in an overblown style, it is a plea on behalf of the wives and children of imprisoned debtors:

The greedy Creditor, whose flinty breast

The iron hand of Avarice hath press’d,

Who never own’d Humanity’s soft claim,

Self-interest and Revenge his only aim,

Unmov’d, can hear the Parent’s heart-felt sigh,

Unmov’d, can hear the helpless Infant’s cry.

Nor age, nor sex, his rigid breast can melt,

Unfeeling for the pangs, he never felt.17

‘Captivity’ was published in the autumn of 1777, just over a year after the Robinsons’ release from the Fleet. It was accompanied by a poetic tale of marital infidelity called ‘Celadon and Lydia’, into which Mary presumably poured some of her anger over Robinson’s philandering. This second volume of poetry was more handsomely produced than the first. Albanesi provided an elegantly engraved title page and the book bore a dedication guaranteed to grab attention: it was inscribed ‘by Permission, to her Grace the Duchess of Devonshire’. The dedication described the Duchess as ‘the friendly Patroness of the Unhappy’ author and ended by ‘repeating my Thanks to you, for the unmerited favors your Grace has bestowed upon, Madam, Your Grace’s most obliged and most devoted servant, MARIA ROBINSON’.

Georgiana Spencer was Mary’s exact contemporary in age, but came from a very different background: born into one of England’s most illustrious aristocratic families in 1757, she became Duchess of Devonshire and mistress of Chatsworth – one of the greatest houses in England – in the summer of 1774, just before the Robinsons went on the run from their creditors. She was already cutting a spectacular figure in London society. Someone mentioned to Mary that Georgiana was an ‘admirer and patroness of literature’. Mary arranged for her little brother George, an extremely handsome boy, to deliver to the Duchess a neatly bound copy of her first collection of poems. She also enclosed a note ‘apologizing for their defects, and pleading my age as the only excuse for their inaccuracy’.18 Georgiana admitted George and asked particulars about the author, as Mary no doubt expected. Georgiana was touched by the plight of the young mother sharing her husband’s captivity. She invited Mary to Devonshire House, her magnificent town residence in Piccadilly, the very next day. Robinson urged her to accept the invitation and she duly went, dressed modestly in a plain brown satin gown.

Mary was mesmerized by the Duchess’s look and manner: ‘mildness and sensibility beamed in her eyes, and irradiated her countenance’. Georgiana listened to her story and expressed surprise at seeing such a young person experiencing ‘such vicissitude of fortune’. With ‘a tear of gentle sympathy’, she gave her some money. She asked Mary to visit again, and to bring her daughter with her. Mary made many visits to her new friend – the two women both beautiful and cultivated, but in such contrasting circumstances. Mary described the Duchess as ‘the best of women’, ‘my admired patroness, my liberal and affectionate friend’.19 They would continue to be closely acquainted for many years. Georgiana loved to hear the particulars of Mary’s sorrows: her father’s desertion, her poverty, her unfaithful husband, her troubles as a young mother, her captivity. She shed tears of pity as she heard the story. Inspired by the Duchess’s patronage, Mary finished the poem that put her reflections on prison life into heroic couplets.

Mary remained unwaveringly loyal to those who helped her. She loved the Duchess and years later paid tribute in verse to her great qualities. She was particularly gratified by her friendship at a time when numerous female companions of happier days had deserted her. It was with the latter in mind that she wrote in her Memoirs of how ‘From that hour I have never felt the affection for my own sex which perhaps some women feel.’ She added with uncharacteristic bitterness: ‘Indeed I have almost uniformly found my own sex my most inveterate enemies … my bosom has often ached with the pang inflicted by their envy, slander, and malevolence.’20 This outburst is, however, belied by the female friendships that she forged and sustained throughout her life.

As spouse of a debtor, she was free to come and go, but the visits to Georgiana were the only time she ever left the Fleet. While she was away from the prison being entertained in the splendour of Devonshire House, Robinson took the opportunity to do some entertaining of his own: Albanesi procured prostitutes for him and brought them into the prison. If the Memoirs are to be believed, after a while Mary was humiliated even further when her husband took to sleeping with prostitutes while she and little Maria Elizabeth were in the very next room. When she confronted him, he brazenly denied the charges.

Despite Albanesi’s supposed responsibility for Tom’s infidelities, the Italian engraver and his glamorous Roman wife became the Robinsons’ closest friends among their fellow detainees. The wife, Angelina, was formerly mistress to a prince and subsequently the lover of the Imperial Ambassador, Count de Belgeioso. Unlike Mary, she chose not to share her husband’s captivity, but she paid frequent visits, dressed to the nines and comporting herself like a duchess. She was a fascinating older woman, in her thirties, a ‘striking sample of beauty and of profligacy’ who gave Mary an insight into the life of a courtesan. She always insisted on visiting Mary when she came to see Albanesi, and she would ridicule the teenage bride for her ‘romantic domestic attachment’. She told Mary that she was wasting her beauty and her youth; she ‘pictured, in all the glow of fanciful scenery, the splendid life into which I might enter, if I would but know my own power, and break the fetters of matrimonial restriction’.21 She suggested that Mary should place herself under the protection of rake and celebrated horseman, Henry Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke – she had already told him about Mary and his lordship was ready to offer his services.

Mary blamed Angelina for trying to persuade her into a life of dishonour. Both the Albanesis filled her young head with tales of ‘the world of gallantry’. Despite the disapproval of the couple expressed years later in the Memoirs, Mary was obviously enthralled by the way in which they offered a window into another world – a world that she had briefly tasted and must have longed to return to. Albanesi sang and played various musical instruments with easy accomplishment. And he told good jokes: Mary would herself become a notable wit.

On 3 August 1776, Robinson was discharged from the Fleet. He had managed to set aside some of his debts and give fresh bonds and securities for others. Mary wrote to her ‘lovely patroness’ with the news – she was at Chatsworth – and received a congratulatory letter in return. At the first possible opportunity, Mary headed for Vauxhall: ‘I had frequently found occasion to observe a mournful contrast when I had quitted the elegant apartment of Devonshire-house to enter the dark galleries of a prison; but the sensation which I felt on hearing the music and beholding the gay throng, during this first visit in public, after so long a seclusion, was indescribable.’22

*Sometimes called Mary and sometimes Maria (both by her mother and herself) – I will call her Maria Elizabeth throughout, to distinguish her from her mother.