Читать книгу Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson - Paula Byrne - Страница 14

CHAPTER 7 A Woman in Demand

ОглавлениеIt has ever been a decided opinion in my mind, that the man who first seduces a woman from the paths of chastity is accessory to all the ills that may await her during the remaining hours of her existence.

Mary Robinson, Walsingham

Mary’s marriage had become a sham. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1779 she accompanied Tom to Tregunter once again. In all probability, he was seeking breathing space from his creditors and wanted to make another attempt to get money out of Harris.

Her reception at Tregunter House was much better than it had been the time when prison loomed: ‘Mrs Robinson, the promising young actress, was a very different personage from Mrs Robinson who had been overwhelmed with sorrows, and came to ask an asylum under the roof of vulgar ostentation.’ Elizabeth Robinson expressed her disapproval of Mary’s profession, but the ‘supposed immorality was … tolerated’ as the labour was ‘deemed profitable’.1 The visit appeared to go well. Harris arranged parties and dinners to show her off. The well-to-do women of the locality treated her as ‘the very oracle of fashion’. After two weeks in Wales, she returned to London to prepare for the new season. On the way home, a pause at Bath exposed her to the solicitations of the dangerous duellist, George Brereton, prominent amongst her husband’s creditors. Tom had met him in the racing town of Newmarket some time before.

Mary’s re-enactment of the story is one of the best scenes in the Memoirs. It reads like a true novel of sensibility. Brereton had married his cousin, the daughter of the Master of Ceremonies at Bath. Despite the Robinsons’ financial difficulties, they stayed at the Three Tuns, one of the city’s best inns. Brereton was initially friendly, but then his attentions turned to ardour: he made ‘a violent and fervent declaration of love’, which ‘astonished and perplexed’ Mary. She thought the best course of action was to leave town and go to Bristol. They checked into an inn there, in Temple Street. The next morning, just as they were going out to make a visit in Clifton, Tom was arrested at the suit of Brereton on the basis of a promissory note ‘in magnitude beyond his power to pay’. A few minutes later, Mary was informed that a lady wished to see her in an upstairs room. Assuming it was one of her old acquaintances, she followed a waiter into another room, while her husband was detained by the sheriff. Brereton was waiting for her: he had got wind of their movements and followed them to Bristol. ‘Well, Madam,’ he said with a sarcastic smile, ‘you have involved your husband in a pretty embarrassment! Had you not been severe towards me, not only this paltry debt would have been cancelled, but any sum that I could command would have been at his service. He has now either to pay me, to fight me, or to go to a prison; and all because you treat me with such unexampled rigour.’2

When she begged for mercy, he asked her to promise that she would return to Bath and ‘behave more kindly’ to him. She realized what he was asking and burst into tears. She accused him of inhumanity. He replied that she was the one being inhuman – for not giving in to him and for making him follow her to Bristol at a time when his own wife lay dangerously ill in Bath. He rang the bell and ordered the waiter to look for his carriage. Mary lost control of herself and screamed that she would expose him as a seducer and villain. Brereton changed colour and tried to calm her down, fearing an embarrassing incident in a public place. He tried to reason with her, asking why she chose to stay with a husband who treated her so badly. It would be an act of kindness to estrange her from such a man. His neglect of her would justify any action she took. Was it not ‘a matter of universal astonishment’ in society that a woman renowned for her ‘becoming spirit’ should ‘tamely continue to bear such infidelities from a husband’? This hit a nerve with Mary, for Brereton was echoing the view taken not only by the gossips in the theatre world but also by her closest circle of friends. At the same time, it was a line that libertines had tried on her before.

Brereton continued to taunt her as she paced the room in anguish. ‘How little does such a husband deserve such a wife,’ he said:

‘How tasteless must he be, to leave such a woman for the very lowest and most degraded of the sex! Quit him, and fly with me. I am ready to make any sacrifice you demand. Shall I propose to Mr Robinson to let you go? Shall I offer him his liberty on condition that he allows you to separate yourself from him? By his conduct he proves that he does not love you; why then labour to support him?’3

Mary was almost frantic. ‘Here, Madam,’ continued Brereton, after pausing four or five minutes, ‘here is your husband’s release.’ So saying, he threw a written paper on the table. ‘Now,’ he added, ‘I rely on your generosity.’ She trembled, unable to speak. Brereton told her to compose herself and to conceal her distress from the staff and guests at the inn. ‘I will return to Bath,’ he said, ‘I shall there expect to see you.’ He stormed out of the room, got into his chaise and drove away from the inn door. Mary hurried to show her husband the discharge. All the expenses of the arrest were settled shortly afterwards. They returned to Bath. Robinson did not ask too many questions. Mary warned him against placing his freedom in the hands of a gamester and his wife’s virtue in the power of a libertine, but she knew he would not listen.

Back in Bath, they moved to a different inn, the White Lion. The next afternoon, a Sunday, Mary was astonished to look out of the window and see Brereton parading down the road ‘with his wife and her no less lovely sister’ – the story of the wife’s dangerous illness was a lie. When the Robinsons sat down to dinner, Brereton was announced by the waiter. He ‘coldly bowed’ to Mary and then apologized to Tom, producing a story about how he had only taken action because he was himself being menaced for the money, that he had come to Bristol to prevent rather than to enforce the arrest, and that he had now paid off the demand. Perhaps he would have the honour of seeing the Robinsons later that evening? They did not wait around for him: immediately after dinner they set off for London. Mary dramatizes this story – like that of her meeting with her husband’s first mistress, Harriet Wilmot – so as to emphasize that she was a wronged woman long before any scandalous liaison of her own, but the vivid details have the ring of truth.

Back in London, the Robinsons rented a spacious and elegant house from the actress Isabella Mattocks, in the heart of Covent Garden, near Drury Lane Theatre. They entertained with abandon: ‘My house was thronged with visitors, and my morning levees were crowded so that I could scarcely find a quiet hour for study.’4 Robinson had a lucky streak with the cards and they spent the money on horses, ponies and a new carriage.

Once again the gossip sheets whispered that the rising star Mary and the dashing theatre manager Sheridan were more than friends. A letter to the Morning Post signed ‘Squib’ said ‘Mrs Robinson is to the full, as beautiful as Mrs Cuyler [another actress]; and Mrs Robinson has not been overlooked; the manager of Drury-Lane has pushed her forward.’ Mary responded: ‘Mrs Robinson presents her compliments to Squib, and desires that the next time he wishes to exercise his wit, it may not be at her expense. Conscious of the rectitude of her conduct, both in public and private, Mrs Robinson does not feel herself the least hurt, at the ill-natured sarcasms of an anonymous detractor.’5 She was learning to play the press, an art for which she had good masters in Sheridan and Garrick.

Sheridan continued to pay her marked attention, but she claimed that – in contrast to the behaviour of the libertines – his attitude was always courteous and respectful. He was too good a friend and a man of too much honour to take advantage of her miserable marriage. ‘The happiest moments I then knew, were passed in the society of this distinguished being. He saw me ill-bestowed on a man who neither loved nor valued me; he lamented my destiny, but with such delicate propriety, that it consoled while it revealed to me the unhappiness of my situation.’ And yet she also writes more defensively: ‘Situated as I was at this time, the effort was difficult to avoid the society of Mr Sheridan. He was manager of the theatre. I could not avoid seeing and conversing with him at rehearsals and behind the scenes, and his conversation was always such as to fascinate and charm me.’6 Is there a hint of some impropriety here? In the original manuscript of the Memoirs a long paragraph immediately preceding this remark is heavily deleted – could Mary have confessed something and then thought better of it? On the other hand, it is striking that the author of the anonymous Memoirs of Perdita, who was for the most part eager to accuse her of having affairs with almost every important man she met, restrained himself in the case of Sheridan: ‘Of the nature of their intimacy, though the tattle of the day may have spoke freely, no particulars have transpired; nor should tattle always be regarded.’7

At this time, Mary was increasingly subjected to the ‘alluring temptations’ of noblemen who wished to take her under their protection. Charles Manners, the fourth Duke of Rutland, offered her £600 a year for the privilege. She turned him down. She wanted the patronage of the theatregoing and poetry-reading public, not that of an aristocrat seeking a courtesan. In her Memoirs, Mary refused to name all the men who propositioned her, so as not to ‘create some reproaches in many families of the fashionable world’.8 But she let it be known that advances were made by a royal Duke, a lofty Marquis, and a city merchant of ‘considerable fortune’. Many of these men conveyed their proposals via Mary’s milliners and dressmakers. The scurrilous Memoirs of Perdita, published in 1784 for the purpose of discrediting her, gives graphic details of her purported sexual adventures with both the conceited dandy Lord Cholmondeley and an unnamed heavy-drinking importer of vintage wines. Though not to be trusted, this source provides incidental confirmation of the impression that men from both the established aristocracy and the world of new city money had designs on her.

One of the men who paid her most attention was Sir John Lade, the wealthy heir to a brewery fortune and former ward of Henry Thrale, friend of Dr Johnson. Soon after coming of age, Lade concentrated all his energies on the Robinson household in the Great Piazza. He gambled with Tom and paid court to Mary. Gossip columnists were soon sniffing round the ménage:

A certain young Baronet, well known on the Turf, and famous for his high phaeton, had long laid siege to a pretty actress (a married woman) at one of our theatres; he sent her a number of letters, which after she had read (and perhaps did not like, as they might not speak to the purpose) she sent him back again; a kind of Bo-peep Play was kept up between them in the theatres, and from the Bedford Arms Tavern and her window. The Baronet is shame-faced, and could not address her in person, but by means of some good friend they were brought together, and on Sunday se’en-night set out in grand cavalcade for Epsom, to celebrate the very joyful occasion of their being acquainted. The Baronet went first, attended by a male friend, in his phaeton, and the lady with her husband in a post coach and four, with a footman behind it; the day was spent with the greatest jollity, and the night also, if we may believe report. Since that time they are seen together in public at the theatres and elsewhere, the husband always making one of the party, between whom and the Baronet there is always the greatest friendship.9

Lade, who later managed the Prince’s racing stables, affected to dress and speak like a groom. He eventually married a girl called Letty, who had been a servant in a brothel. Lady Letty Lade went on to have affairs with both the Duke of York and a highwayman known as ‘Sixteen-string Jack’.

As rumour spread that Lade had won the affections of the actress, every rake in London began seeking the acquaintance of the beautiful Mrs Robinson. Sheridan was worried that his star would be tempted away by one of the men who were paying court to her. He warned Mary about her expensive lifestyle and the company she kept. The image of her younger self that she presents in the Memoirs is, to say the least, wide-eyed: ‘I had been then seen and known at all public places from the age of fifteen; yet I knew as little of the world’s deceptions as though I had been educated in the deserts of Siberia. I believed every woman friendly, every man sincere, till I discovered proofs that their characters were deceptive.’10 Given all that she had seen in both high society and low, she could not really have been that naive.

Despite the fact that she was treated as public property by the men who pursued her, Mary evoked this time as a golden age of theatre. Sheridan was at the peak of his reputation as a playwright and manager, following the success of his School for Scandal. He was beginning to turn his mind towards a political career and had recently met the young radical politician Charles James Fox. The green room was frequented by the nobility and ‘men of genius’ such as Fox and Lord Derby, who was to marry Elizabeth Farren: ‘the stage was now enlightened by the very best critics, and embellished by the very highest talents’. Mary also remarked that one of the reasons for Drury Lane’s popularity during this season of 1779–80 was that nearly all the principal women were under the age of twenty (a slight exaggeration). As well as herself and Farren, the lovely Charlotte Walpole and Priscilla Hopkins were on the payroll.

The public’s appetite for news, gossip, and scandal about the stage was insatiable. One of the consequences of the system of stock companies was that the audience became familiar with a small group of actors, seeing them in a variety of different roles and plays of all types, coming to know not only their styles of acting, but the details of their private lives. The proliferation of stage-related literature meant that readers were able to discover the intimate details of actors’ lives. A successful player could only have a public private life. Actors’ journals and memoirs, biographies of playwrights and managers, histories and annals of the theatre, periodicals and magazines rolled off the press. Prints and caricatures of actresses could be bought cheaply. Theatre gossip could be picked up from the newspapers, together with instant accounts of the latest performances – this was the age when professional theatre reviewing grew to maturity.

Sheridan launched his new season on 18 September 1779 with Mary as Ophelia. ‘Natural and affecting,’ said the Morning Chronicle. ‘Ophelia found a more than decent representative in Mrs Robinson,’ judged the Morning Post, ‘except in her singing, which was rather too discordant even for madness itself!’ It also noted that ‘the house, though not a very brilliant [i.e. aristocratic], was a crowded one, and both play and entertainment [the musical Comus] went off with considerable éclat’.11 Mary was Lady Anne in Richard III a week later.

Next, she reprised her Fidelia in The Plain Dealer. Her costume drew attention, though the critic in the Morning Post tried to give the impression that he was only looking at it from the point of view of dramatic verisimilitude, not that of the shapely leg to which it clung:

Fidelia was performed with great ease and feeling by Mrs Robinson, and is by far the best character she has hitherto attempted; but as propriety of stage dress should always be strictly attended to, particularly in the professional characters, it may not be improper to inform Mrs Robinson, that Fidelia as a Volunteer cannot wear a Lieutenant’s uniform, without a violation of all dramatic consistency.12

She played fifty-five nights that season, adding to her repertoire Viola in Twelfth Night, Nancy in The Camp, Rosalind in As You Like It, Oriana in George Farquhar’s The Inconstant, Widow Brady (‘with an Epilogue Song’) in Garrick’s The Irish Widow, and Eliza Camply in The Miniature Picture by Lady Elizabeth Craven. As Oriana, she had to win over a reluctant lover by engaging in various schemes including dressing as a nun, feigning madness, and disguising herself as a page-boy. As the Irish Widow, she had to mimic a strong brogue, put down an assortment of men, talk about her clothes, claim that she despised money, and cross-dress as a sword-bearing officer called Lieutenant O’Neale. But it was the Shakespearean breeches roles of Viola and Rosalind that were her greatest triumph. She revealed a gift for both the expression of Shakespeare’s language and the characters’ emotional range – from pathos through wit to fortitude and command.

Admirers began to address her through the medium of the daily press. The Morning Post printed a long and not a little voyeuristic letter to her. ‘Madam,’ it began,

Criticism is a cold exercise of the mind: but as I feel an inexpressive glow, while my imagination takes your fair hand in mine, I think I may venture to court your acceptance of two or three remarks, which are conveyed in a temperament of blood somewhat differing from the chill, and the acid of the critique. I am the veriest bigot to old Shakespeare. – The Genius himself could not have gazed upon you with more delight; nor have forerun your motion, action, and utterance, with more tremulous solicitude for your excellence in Viola, than I did. Shakespeare’s principal substantives should never be sunk, nor kept back, as it were, from the attention, by an emphatic tone upon his epithets.

In the manner of speaking the ‘green and yellow melancholy,’ I would, sweet woman, that the yellow tinge appeared no more than equal to the green; and, that the melancholy so coloured should have a principal share of your voice to mark the subject.

I have seen you too in Fidelia, and am apt to think, that the tone, force, and manner of tragedy make a kind of apparel, both too magnificent, and too solemn, for the sentimental part of comedy.

BO-PEEP13

The author sounds as if he would very much like to pay a private visit to her dressing room in order to advise her upon her Shakespearean epithets.

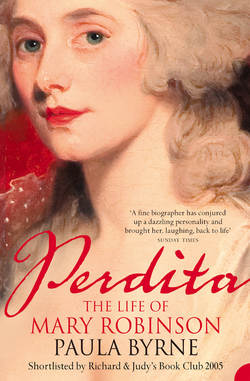

She also played the female lead in Florizel and Perdita. This was Garrick’s 1756 version of the final two acts of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. It was revived by Sheridan, after fourteen years’ absence from the repertoire, on Saturday, 20 November 1779, in memory of Garrick, who had died earlier that year. It centred on the young lovers, Prince Florizel and Perdita, who is supposed to be a shepherd’s daughter but is really a princess. It included a sheepshearing song, sung by Perdita, and a dance of shepherds and shepherdesses. Mary’s performance was a success, though the Morning Post complained ‘Mrs Robinson’s Perdita would have been very decent, but for that strange kind of niddle to noddle, that she now throws into every character, comic, as well as tragic.’14

At the second presentation, the following Tuesday, she was honoured by the presence of such leaders of London society as the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, Lord and Lady Melbourne, Lord and Lady Spencer, Lord and Lady Cranbourne, and Lord and Lady Onslow. After this performance the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser published a long criticism. It said that the piece ‘is in general well cast and ably performed’, but reservations were expressed about the costumes:

The dresses on which much of the effect depends, were liable to very glaring objections. Shakespeare has been particularly attentive to the dress of Florizel and Perdita:

Your high self you have obscur’d

With a swain’s wearing, and me poor lowly maid,

Most goddess-like, prank’d up—

To correspond with this description Florizel and Perdita have hitherto appeared in beautiful dresses, covered with flowers of both the same pattern, and she wore an ornamented sheep hook, instead of which Mrs Robinson appears in a common jacket, and wears the usual red ribbons of an ordinary milk-maid, and in this dress she also appears with the King to view the supposed statue of Hermione, after she is acknowledged his daughter.15

For most of the audience, though, the figure-hugging jacket and milkmaid’s ribbons were exactly what they wanted to see. Takings were excellent and the show played again on the next Friday night and the Monday and Wednesday after that. Mary gained further public exposure when the Morning Post printed her poem ‘Celadon and Lydia’.16 Then on Friday, 3 December 1779 there was a royal command performance. A full house was assured. Mrs Robinson was about to become ‘the famous Perdita’.