Читать книгу Manxmouse - Paul Gallico - Страница 8

Chapter One THE STORY OF THE TIDDLY MOUSE-MAKER

ОглавлениеThere was once rather an extraordinary old ceramist who lived in the village of Buntingdowndale in the heart of England. Ceramics is the art of making pottery into tiles, or dishes, or small glazed figures.

What was unusual about him was that he only made mice. And they were not the ordinary kind either. Other potters in the village, and there were several, turned out birds or dogs, kittens or rabbits and many different kinds of animal, but this one made nothing but the most lifelike and enchanting little ceramic mice from morning until night.

He was a happy fellow who hummed to himself contentedly throughout the day as, with his clever fingers, he modelled mouse after mouse after mouse. In the evening he would put those that were dry into a special oven and let them bake overnight. Then the next day he would take them out, polish them, file off the rough edges and look at them lovingly before either setting them in the window of his shop in Buntingdowndale or sending them off up to London.

He probably knew more about mice and their ways than anyone else in the world, so that he was able almost to think like a mouse.

He had come to know them so well because he had mice in his workshop – not in a cage of course, but whole families of them who lived there behind the wainscoting and underneath the wooden floor.

They were quite used to him and since he did not keep a cat, they would come out from their homes and go about their business across the room, or sit up to have a chat together as though he were not there. Sometimes he felt he could almost understand what they were saying. Thus he came to have a great affection for them, copying them in all kinds of poses. He made them as he saw them, coloured brown, grey or white, but their ears were always of a delicate pink and nearly transparent.

But just because he was so fond of them and so knowledgeable, he was never wholly satisfied with the results of his work. Something he felt each time escaped him – some attitude of the body, or expression of their faces. Oh, he made them look worried all right, since he knew that no sensible mouse ever relaxed entirely, even when there was no cat in the house. For there were other things to upset them: terriers, birds of prey, not to mention stoats, weasels and foxes. Then there were traps set by people, and the everyday business of seeking out a living for their families and themselves.

And so the old gentleman’s mice always seemed to be peering slightly nervously over their shoulders. Yet he felt that there was something about mousedom that he had failed to capture. But every time he set about his work, he was hoping that this next one would result in the absolutely faultless or super mouse.

So the days passed; people came from far and near to buy his figures, for they thought them perfect. But the ceramist was beginning to wonder whether before it came his time to pass on, he would ever be able to make a completely one-hundred-per-cent, satisfying reproduction.

And then, out of the blue, something happened. Sometimes when one has had an ambition for a lifetime, worked hard and tried faithfully, one can brew up a magic moment when suddenly all things seem possible. It was not exactly like that with this potter. The strange thing was that the feeling came to him on a day when he had not planned to do any work at all. For there was to be an important wedding of the daughter of friends in Buntingdowndale, and of course he had been invited.

It turned out to be a very happy and gay affair indeed, lasting all day. Beginning with the marriage in the morning there was a large luncheon with many toasts in cider drunk to the bride and groom. After the happy pair had left, it was far too early to go home, so the potter with several of his cronies went to the village inn, The Cat and Mouse. He was particularly welcome there, for he had modelled the sign that hung over the door, in which the mouse was as large as the cat and the two were marching hand-in-hand and smiling cheerfully at one another. This idea, naturally, was quite absurd but it was so amusing and charmingly done that it had resulted in making the inn rather famous.

There, without regard to the clock, or the call of other duties, the friends continued to raise their glasses to the health and future happiness of the married couple, until to their great surprise the inn-keeper was compelled to announce closing time. Thereupon they rose and departed, each to his home in his own manner, with the ceramist finding it easier to float than to walk.

For he was feeling as though he weighed almost nothing, and he was exceptionally happy, joyful and contented.

The village street by lamplight had never looked more beautiful, nor the stars above brighter and it seemed to him that if he wished he could reach up and touch the moon. Some kind of enchantment was at work.

As he turned into the gate of his cottage he thought it was a pity to put such a feeling to bed and to sleep. And so instead of entering the door, he turned off and drifted down the path to his workshop which was at the bottom of the garden. There he switched on the lamps and, light as a feather, settled down at his pottery bench by the bins of different kinds and grades of clay that he used. Before his eyes swam his jars of paints and glazes in all hues, his brushes and his modelling knives. At the far end his electric oven with its knobs, switches and levers appeared to form itself into a face and figure with arms outstretched in invitation.

And thereupon the sensation came over him most intensely and the idea smote him like a stroke of lightning: Now! Now, this very moment, here tonight, this instant, I shall make my super mouse.

At last, at last! Everything that he ever seemed to have known about mice and the making of glazed ceramic figures, came together. And at that particular instant he felt he was the greatest ceramist the world had ever known, and that the mouse that he was about to make would be the most beautiful and perfect that anyone had ever seen.

His coat apparently removed itself without his aid. When he slipped the string of his potter’s apron over his head, it tied itself around his waist. And since his feet no longer needed to touch the ground, it was no effort at all for him to move quickly about his workshop.

He decided to use his favourite mixture – two parts of Copenhagen clay which he imported from Denmark, combined with one part from the banks of the Deedle, the brook that meandered through Buntingdowndale. This he moistened and worked together into a ball. Never had this part of the work gone so well.

With a singing in his heart he reflected upon what a wonderful artist he was and with the picture of this mouse in his mind, he began to model.

It was a sitting-up one upon which he had decided. It would be perched on its hindlegs with its two tiny paws held in front of its breast, clutching the end of its tail which would come winding out from beneath it, up around its side and over one arm.

That night his fingers were so thin and sensitive that he did not need any of his modelling knives, not even to etch the fine whiskers sprouting from its cheeks. For these he used his thumbnail. He was particularly proud of the ears. He knew that when glazed and fired, one would be able almost to see right through them, as he could see through the ears of the live ones who came to visit him.

‘What is art?’ he said to himself, and then answered, ‘Art is creation and I am a creator.’ And he felt even better and happier.

It was the same with the preparation for the painting and glazing. He had only to think about what he wanted and there it was. All his skill, knowledge, cunning and experience were brought into play here. One had to know exactly the right mixture of colours, so that when the clay emerged from the furnace, the heat would have baked it into exactly the proper shades.

This was to be a dark grey mouse when it was finished. He applied the paints lovingly and with care. The tiny upstanding ears would be grey outside and their shells the faintest shade of pink, the colour of the very beginning of dawn. The tail was like the coat, dark grey at the base and growing lighter as it climbed up around the side of the mouse, until it disappeared into the paws of the little animal. The very end was hardly any colour at all, which was a most artistic and lifelike achievement. For, as everyone knows, there is no hair at the tip of a mouse’s tail and this is very difficult to copy. Yet for the ceramist that evening, nothing was impossible. But this was not all that he felt he was accomplishing, merely the making of a purely physical copy of one of his little grey friends from behind the wainscoting. Oh, no! On this very special and extraordinary occasion the ceramist felt that he had hit upon the secret of why his other creations had been failures in his own estimation, and this one was to be a success. It was because he had applied himself too much to the form and not sufficiently to the spirit. And so, concentrating most tremendously upon this master mouse, he tried to instil all the wisdom and knowledge that he himself had accumulated during his lifetime: mouse knowledge, people knowledge, things knowledge.

Of course, although the ceramist knew a great many facts, there was also a good deal he did not, since it is not possible to know everything. But this did not worry him. He was pouring all of himself that there was into the little creature that was so smoothly and beautifully taking shape beneath his fingers.

At last it was finished. He placed his creation upon an already baked tile and stood back to contemplate his handiwork. He could hardly bear to lock it up inside the oven and tear himself away from it. And yet if he wished to see it in its utmost perfection the next morning, delicately coloured and exquisitely glazed, he must of necessity do so.

‘I am indeed a great artist,’ he murmured, highly pleased with himself. He gently lifted up the tile which bore his sculpture and placed it in exactly the right position in the centre of the electric furnace, so that the heat would reach it evenly from all sides.

‘Bake well, my little fellow,’ he said, ‘and tomorrow you will be a masterpiece.’

With this he examined the instruments to see that the temperature was rising properly and the thermostat working, and then, forgetting to switch off the lights in his workshop, he went out into the garden where he performed an impromptu dance of joy in celebration of his accomplishment. It was a good thing that it was so late and the neighbours all abed, for they would have been most astounded had they seen the elderly, bespectacled ceramist leaping and pirouetting about upon the lawn.

When he had finished, he swam up the garden to his house. True, there was no water there, the night still being fine and dry, but at that moment he felt it would be lovely to swim along the path, through the cool grass. And so he did so, around and past his shop into his adjoining home, breast stroking his way up the stairs and right inside his bed, where no sooner did his head touch the pillow than he was instantly asleep. He dreamt that a gold medal was being handed him for creating the finest porcelain mouse ever.

When he awoke the next morning he was not feeling at all as well as he had upon retiring. Far from being able to float, he now seemed anchored to the bed because his head weighed as much as though it were made of lead. He had to put one foot at a time on to the floor and then saw to his amazement that he had not removed his clothes the night before. He wondered whether perhaps he was gravely ill. But then he remembered the wedding and the many glasses of cider that had been lifted, and the continuation of the party afterwards with his chums at The Cat and Mouse. What had occurred after that he did not recollect at all. He splashed cold water on his face, which did not help a great deal, and after drinking a number of cups of coffee, tottered off to his workshop.

To his astonishment he saw the light burning inside and his first thought was, Burglars!

He found the door unlocked which gave him further cause for alarm, and he hurried in to where another surprise awaited him. He observed that his electric oven was turned on to top heat, which was puzzling since he knew he had done no work the day before, but had attended a marriage instead.

Suddenly it began to come back to him, and he murmured, ‘But of course, now I remember! Last night when I came home I made the most beautiful and the finest mouse of my whole life. Now I shall look at him.’

He switched off the oven and when it had cooled sufficiently, threw open the door. With hands that trembled slightly, he seized his pair of tongs and carefully withdrew the supposed mouse masterpiece from the depths of the stove and set it upon his workbench.

And then, with his eyes almost popping from his head and the most terrible sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach, he saw that what he had produced was not only no super creature, but a disaster second to none in the history of ceramics.

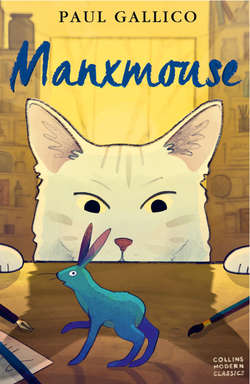

In the first place, it was not grey but an utterly mad blue. It had a fat little body like an opossum, hind feet like those of a kangaroo, the front paws of a monkey and instead of delicate and transparent ears, these were long and much like those of a rabbit. And what is more, they were blue too, and violently orange-coloured on the inside.

But the worst thing of all was that it had no tail. The ceramist examined the mouse from every angle and there was none to be seen, although at the back was a small button where one once might have begun. He had either forgotten to make it or, even more horrible thought, had been careless in its production and it had broken off.

Goodness knows, it didn’t look like much of a mouse, what with no tail and rabbit’s ears and wild blue in colour, but still it felt like a mouse and in some curious way was one. But, of course, as a ceramic it was a total failure.

And suddenly the artist threw back his head and began to roar with laughter as he said to himself, ‘Well, I must have had a fine night. After coming here I can’t remember a thing. Certainly no one ought to set about making porcelain mice, or anything else, when one has had several ciders over the eight.’

Now he examined the muddle of his clay and colourings and chemicals on the workbench and laughed even louder. He had used all the wrong materials and colours and had apparently just pulled any old chemicals off the shelf. And, of course, worst of all, he had not waited for it to dry before painting, glazing and baking. It was a wonder that anything at all had resulted from the mess.

One thing was certain, it was not the kind of product that a self-respecting ceramist would want to keep about his studio in case anyone should embarrass him by asking what it was. And so he raised a wooden mallet and was about to bring it down to smash it into dust, when something about the expression of the little creature caused him to stop.

To his surprise he found that the look on the face of the so-called mouse was peculiarly unusual and endearing.

The worry, the fear, the timorousness and feeling of wanting to glance over its shoulder to see whether the cat was around was missing. None of that. What it did have was a combination of interest and excitement with a little shyness and a great deal of sweetness.

If you looked at him from one angle, his face seemed to say, ‘I love you! Please like me.’ And from another, its expression was, ‘I’m such a small mouse, I really don’t matter to anyone. But I’d be happy to help you in any way I could.’

The ceramist laid down his mallet and picked up the porcelain piece which was now cool, and the gentleness and differentness of its face made him smile. Turning it around to the place where its tail should have been, he examined the button and then said, ‘Oh, well, so I’ve made a Manx Mouse.’

He was referring to the fact that the creature had no tail, like the cats from the Isle of Man who, as everybody knows, are tail-less too, and are known as Manx Cats.

The figure looked so absurd that he was forced to smile again. ‘Then I’ll keep you to remind me to say “No thank you” next time I’m invited to have just one more glass.’

In the evening he took the Manx Mouse to his room and put it upon his bedside table where it sat up and regarded him with a mixture of longing and affection, until he put out the light.

Now a strange thing occurred that night, so odd that when the ceramist told it to one of his chums he swore that he had imbibed nothing stronger than a glass of lime and barley water before retiring. For he was not aware that, in spite of the weird results, cider or no cider, all the love and hopes he had poured into the making of this one mouse had called forth the magic of a true creation. And when that has taken place, anything can happen.

Thus it was that he woke up in the dark, or thought he did, with the feeling that the chiming clock in the living-room downstairs was about to strike, which indeed it did. He counted the strokes to know the time and how much longer there was left to sleep. And so he counted: eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen.

Thirteen! But that was absurd. No clock ever struck thirteen, and particularly not his faithful grandfather piece which had been in his family for years.

He had half a mind to get up and go downstairs and see what time it really was, but suddenly found himself drowsy and unable to keep his eyes open any more.

The following morning when he awoke, something even stranger had happened to occupy his attention. The Manx Mouse was no longer on his night table.

At first he thought that he must have knocked it off and so he looked on the floor and even crawled under the bed. But there was nothing there. Then he thought that perhaps it had got mixed up with the bedclothes, so he shook these out most carefully. But there was no Manx Mouse.

He then remembered vaguely what must have been a dream of the clock striking thirteen. This and the disappearance of the blue Manx Mouse was, to say the least, disquieting. He searched his room, looking in every nook and cranny and even in cupboards, bureau drawers and on top of shelves until there was not an inch that he had not inspected. In great perplexity he sat down on the edge of his bed and did not know what to think or where it could have gone, but finally had to give up.

And thus, having played his part, the ceramist now vanishes from our story.

But for Manxmouse, the adventure had just begun.