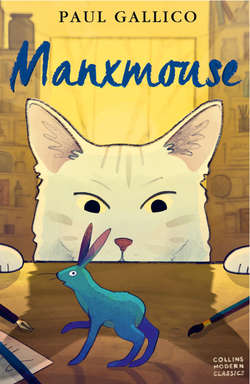

Читать книгу Manxmouse - Paul Gallico - Страница 9

Chapter Two THE STORY OF MANXMOUSE AND THE CLUTTERBUMPH

ОглавлениеIt was shortly after the stroke of thirteen that Manxmouse realised that he was sitting up on a night table next to a bed, where a mouse really had no business to be.

The moonlight was pouring in through the window, making a pathway to the door which was open.

There was a man asleep in the bed and he was snoring. But he might wake up at any moment and Manxmouse thought he had better go. He slid down one leg of the table quite handily and slipped over to the side of the room for a bit of shadow to think things over for a moment. For although he was certain that he ought to be going, he did not know where to.

It was a most curious feeling not to have been aware of being anywhere a few instants before and then quite suddenly to be not only somewhere, but someone. Perhaps that was what it was like to be born.

From the general shape of things he seemed to be a mouse and indeed, he felt like a mouse and so he must be one. But for the rest, how he had got on to a night table and who, and what, and where he had been when he was not anything or anybody, or even any place for that matter, was too difficult to understand. He did not even know his name, or if he had one. Thinking about it was beginning to give him a headache. If he was going to be on his way, now was the time to do it, before somebody came and shut the door.

He then did a very unmouselike thing. Instead of keeping to the shadows at the side of the room, he marched straight along the lighted path laid down by the moon across the carpet, to the door, climbed the newel post at the top of the stairs and slid down the banisters. He got out of the front door and into the street through the letter-box.

Every single soul in Buntingdowndale must have been asleep. Except for a street lamp, not a light showed anywhere. No one was about and even the houses had their eyes shut with blinds or curtains drawn.

There was a slight breeze blowing, bearing the scent of distant flowers and dew on grass. He thought he would be more comfortable in the country than in the midst of this brick, stone and glass. However, no sooner had he started off when, without warning, he encountered a Clutterbumph on the prowl through the village. It was looking for someone to entertain with a bad dream or a little agreeable terror in the night.

This was somewhat unusual, since it takes two to make a proper Clutterbumph.

For a Clutterbumph is something that is not there until one imagines it. And as it is always someone different who will be doing the imagining, no two Clutterbumphs are ever exactly alike. Whatever it is that frightens one the most and which is just about the worst thing one can think of, that is what a Clutterbumph looks like.

The Clutterbumph usually announces itself with a noise somewhere in the house during the night; a creak in a floorboard or a piece of furniture as it cools after the heat of the day, a drip from a tap, the rattle of a loose shutter, a fly buzzing on a windowpane, something scurrying in the attic, or a cricket caught in the coal cellar.

One could conjure up something with a sheet over it and two eye-holes, sitting on the end of the bed, or an ugly witch with a tall hat and hooked nose on a broomstick. Or perhaps one could imagine something that has too many legs and stingers fore and aft, or a great bear with fiery eyes and long claws and teeth. Or make it a one-eyed, snaggle-toothed giant nineteen feet tall, a dragon, a devil with a pitchfork, or just two googly eyes that keep staring.

The point is that the Clutterbumph cannot exist to frighten anyone unless that somebody thinks of it first and decides what it is going to be like. And when one had finished enjoying being frightened and does not want to be any longer, one simply stops thinking of the Clutterbumph, or falls asleep and it is not there any more.

Since Manxmouse was not imagining anything at the time, this particular Clutterbumph was as yet without any shape or form. In fact it was invisible and in its approach to Manxmouse it had to limit itself to such noises as, ‘Whooooooo!’ and ‘Ha!’ and ‘Grrrr!’ and also, ‘Ho, ho, ho!’ along with ‘Boo!’ or ‘Shoo!’ which last are rather old-fashioned and do not frighten anyone any more.

Although Manxmouse could see no one, he thought he heard somebody speak and so he said, ‘Good evening,’ politely.

The Clutterbumph let out a screech. ‘Whoooeee! Good evening, indeed! We’ll see about how good an evening it is.’ And at this it snarled, growled, howled and roared. It stopped suddenly and in a more natural voice inquired, ‘Look here, aren’t you afraid?’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Manxmouse.

‘Oh, I say,’ said the Clutterbumph in slightly injured tones, ‘that’s not playing the game. You’re bound to be frightened of something: witches, ghosts, demons, dragons, monsters plain or fancy. I’m not particular, and I’ll be glad to oblige. Just think what it is that scares you the most and then I’ll be with you in a jiffy. Perhaps I haven’t introduced myself. I’m a Clutterbumph.’

Manxmouse genuinely wished to oblige the Clutterbumph, whatever it was, but found himself unable to do so. He said, ‘I’m sorry, I really can’t think of anything I’m frightened of.’

‘Come, come!’ said the voice. ‘That’s ridiculous. Not scared? What about dark corners when you never know what’s going to jump out at you? That’s something I do beautifully, by the way. I was first in my class jumping out from dark corners.’

‘Please excuse me,’ Manxmouse apologised, ‘but you see, I haven’t been here for very long and perhaps don’t know how.’ Which was quite true, since the ceramist had forgotten to put fear into him.

The Clutterbumph tried a different tack. He said, ‘Let’s be sensible. You’re a mouse, aren’t you?’

‘I think so,’ said Manxmouse.

‘Well then,’ cried the Clutterbumph triumphantly, ‘you ought to be afraid of Cat. Ha! Wait till you see the kind of cat I can be. Made the Honour Roll for it – glowing eyes, cruel claws, sharp teeth, lashing tail and frightful growl. How about that?’

‘But I’ve never seen a cat,’ Manxmouse said.

‘You’re not being at all co-operative,’ and a plaintive note crept into the voice of the Clutterbumph. ‘Here I am, out on a job, one of the best of us, if I may say so – graduated with honours, with a gold medal for my appearance as a bogey, and I can’t take shape and get on with my work unless you imagine me. Come on, now, there’s a good mouse. Think up something simply awful.’

Manxmouse obviously wished to help and tried very hard, but nothing would come since, as he had already told the Clutterbumph, he had not been there for very long. And the truth is that no one is ever born frightened or fearing anything.

At last, after a period of awkward silence, the Clutterbumph moaned, ‘All right, I give up. Forget about it. I’ve never been so humiliated in my life. What will they say back at the office, when they find out? A Clutterbumph who couldn’t frighten a mouse! Oh dear, oh dear!’

‘Do forgive me,’ said Manxmouse.

The mouse was so plainly distressed, that the Clutterbumph said, ‘That’s all right. I shan’t hold it against you. But if you wouldn’t mind me giving you a little piece of advice …’

‘Oh, no, not at all,’ said Manxmouse. ‘It would be very kind of you.’

‘Well,’ said the Clutterbumph, ‘I see you’re a Manx Mouse.’

Since the Clutterbumph was invisible and, in fact, actually wasn’t there, it was difficult to understand how he could ‘see’ anything. Nevertheless, Manxmouse replied, ‘Am I?’

‘Oh, yes, undoubtedly. Anyone with half an eye, or even with no eyes like myself can see that. Well, my advice is Beware the Manx Cat.’ And with that he flew off into the night with his ‘Grrrrs’ and ‘Booos’ and ‘Arrghs’ growing fainter and finally dying out altogether.

Manxmouse wondered what it was the Clutterbumph had meant, but he was growing tired and so he went on in the direction of the country smells until he came to the edge of Buntingdowndale where the pavement ended.

He walked on for a little while longer, enjoying the feel of grass and leaves and earth and twigs beneath his feet. Just as the moon was beginning to set and the stars to pale, Manxmouse found a soft spot under a hedge, curled up and went to sleep.

When he awoke it was broad daylight. The sun had been shining long enough to dry the dew from the grass and the flowers. It was warm and comfortable. As Manxmouse emerged from under his hedge, he saw that he was at a road junction with an old signpost leaning slightly askew. One fingerboard pointing to the right was marked LITTLE GREAT MUNDEN, and the other pointing to the left was lettered, NASTY. A Billibird perched on top of the signpost, manicuring its fingernails.

A Billibird carries a tail light, can fly backwards as well as forwards and sideways, and knows a great deal about a lot of things, but not everything.

The Billibird stopped doing its nails and said, ‘Hello, a Manx Mouse! Or am I dreaming?’

It was strange, Manxmouse thought, how everyone he encountered seemed to know what he was, when he was not at all sure himself. He knew that he was a mouse, but not that kind of a one. For it must be remembered that as yet he had not seen himself.

‘I was just wondering which way to go,’ Manxmouse said.

‘Well,’ said the Billibird, ‘you have a choice of one or the other. And you needn’t worry, there’s no Manx Cat either way. Little Great Munden has five houses in the Little part and six in the Great part, and its own post office. Nasty has only four houses and the post office is in the kitchen of the last one.’

‘Is there really a place called Nasty?’ asked Manxmouse.

‘Well, it says so, doesn’t it?’ replied the Billibird, indicating the signboard. ‘So I suppose there must be. I know some villages with even funnier names. There’s one called Pity Me and another Come-to-Good. And then there’s the one you ought to know about. It’s called Mousehole, although they pronounce it Mouzle. The villagers try to pronounce Nasty as Naystie, but it’s Nasty all right, and there’s nothing they can do about it.’

‘It must be horrid, then,’ Manxmouse suggested.

‘Oh, no, on the contrary, it’s delightful – timbered houses with thatched roofs, early Elizabethan style, I take it; the most charming gardens and a pretty little pond. Nice people, too. I often go there myself.’

‘Then however did it get that name?’ inquired Manxmouse.

‘Now that is one of the things I don’t know,’ replied the Billibird, ‘and there aren’t many. Someone just called it that, and there it is.’

Manxmouse made up his mind. ‘Then that, I think, is where I shall go for I’m getting hungry.’

‘Mind,’ said the Billibird, ‘there’ll be cats. But they’re well fed and oughtn’t to bother you, except maybe old One-Eye or Street Cat. But of course it’s really Manx Cat you want to watch out for.’

The Billibird resumed its manicuring and as Manxmouse thanked it and went off down the road in the direction of Nasty, he heard it say, ‘I’m not dreaming. I know I’m not. It actually is a Manx Mouse. Poor thing!’

Manxmouse wondered why, ‘Poor thing’? For he was quite happy.