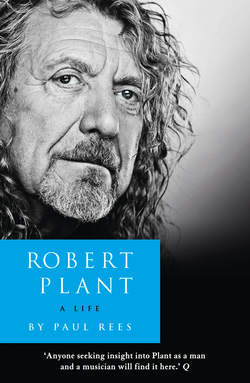

Читать книгу Robert Plant: A Life: The Biography - Paul Rees - Страница 5

Оглавление

How can you ever tell how it’s going to go?

For a moment he was alone. Back in his dressing room, where he had paced the floor little more than two hours before. Then, he had been in the grip of a terror at what was to come. The weight of history pressing down upon him; the burden of all the demons he had come here to put to rest at last.

He had felt fear gnawing away at him. The dread of how he might appear to all the thousands out there in the dark. Here he was, a man in his sixtieth year, desiring to roll back time and recapture all the wonders of youth. Did that, would that, make him seem a fool? In those long minutes with himself he had looked in the mirror and asked over and over if he really could be all that he had once been; if it were truly possible for him to take his voice back up to the peaks it had once scaled. He had so many questions but no answers.

There would be ghosts in the room, too. Those of his first-born son, of his best friend and of all the others he had lost along the way. For each of them he wanted to be the Golden God this one last time …

It was going on midnight on 10 December 2007. Robert Plant was gathering himself in the immediate aftermath of Led Zeppelin’s reunion concert at London’s O2 Arena. The roar of the crowd, which had rolled over him like thunder, had faded. He could hear the chatter of many voices in the corridors backstage; the same corridors that had earlier been silent and still, pregnant with expectation before he and his band had walked tall once more.

Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, the other surviving original members of Led Zeppelin, were off in their own corners thinking their own thoughts. Tonight they had come together but there would remain a distance between them. It was one that spoke of all they had built together and then seen turn to ruin; of shared victories and bitter recriminations; of relationships so complex and complicated they were all but impossible to unravel.

When at last Plant threw open his door, all of those who came to shake his hand and pound his back told him what he already knew. He, they, had been great. Better than anyone could ever have hoped they might be. His doubts had been stilled. His debt, such as it was, had been honoured.

Pat and Joan Bonham, wife and mother of John, the friend and colleague he had buried a lifetime or a heartbeat ago, were among the last he welcomed and he held them especially close. Jason, their son and grandson, had sat in his father’s drum seat that night. He told them how proud John would have been of his only son. And then the ghosts came to him again.

He was supposed to go to some featureless hospitality room upstairs to meet with friends. There was a VIP party to attend where he would be feted by Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger, Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell, Priscilla and Lisa-Marie Presley, and more and more. He instead took one last look around the scene of his triumph, then summoned a car and asked to be driven away from it. He wanted nothing more now than to get as far from everyone and everything as it was possible to be.

‘The rarefied air backstage at the O2 was something you could only savour for moments,’ he told me three years later.

On that cold, dark night he drove north, across the River Thames and through city streets aglow with Christmas lights. On to Chalk Farm, a corner of north London a mile from the bustle of Camden Town and a short walk from the more genteel Primrose Hill, where he had a house. The car dropped him off at the Marathon Bar, an inauspicious-looking Turkish restaurant on Chalk Farm Road.

Going inside, he walked past two spits of grey meat cooking in the window, past the stainless-steel counter and the garish display board advertising kebabs, burgers and fried chicken. He went into the small, windowless back room. There he sat at a wooden table, and ordered half a bottle of vodka and a plate of hummus. They knew him in this place and let him be. Here, at last, among the Marathon Bar’s usual late-night crowd – the young bucks, the couples and the local gangsters – he felt at peace. Through an open archway he could look out over the restaurant’s main room and onto the street beyond.

I first met Plant in 1998 when I was working for the British rock magazine Kerrang! At the time he and Page were about to release their second album together as Page and Plant, Walking into Clarksdale. I interviewed the pair of them in London. During the course of our conversation Plant veered back and forth from being testy and disinterested to disarming and expansive, and I found him hard to read. I was fascinated by him because of this, drawn as much to his contradictions as to his obvious charisma. The quieter and more fragile-seeming Page left a much less enduring impression.

Our paths crossed a number of times during the years that followed. We shared a journey on a public ferry in Istanbul, and I bumped into him in the backstage corridors at assorted television and music-awards shows. Discovering I was both a fellow Midlander and a football fan, he appeared to warm to me – although the team I supported, West Bromwich Albion, were local rivals of Wolverhampton Wanderers, the one he had followed from boyhood. One summer he sent me a couple of emails proposing a bet on the outcome of a forthcoming game between the teams. I am still waiting for him to honour this wager – a meal in an Indian restaurant on London’s Brick Lane.

I interviewed him again in 2010, this time for Q magazine and when he was basking in the afterglow of the success he had enjoyed with Raising Sand, the album he had recorded with the American bluegrass singer Alison Krauss. He was warmer and friendlier on this occasion, and also appeared more at ease. This was perhaps as a result of how well both Raising Sand and his work subsequent to it had been received, or just as likely because Page was absent. He reflected on his formative years in England’s heartland, on the wild ride he had taken with Zeppelin and on his solo career, through which his fortunes had been as varied as the albums he had made.

Two things that struck me most about Plant were his passion for music – which burns as fiercely now as it did when he was captivated by the great American blues singers as a grammar-school boy – and the uniqueness of his story. The best work of the vast majority of his peers is many years behind them but Plant continues to seek new challenges and adventures. This has kept his music fresh and vital, filling it with surprises and delights. Such was the spark for this book, fanned by the knowledge that no one had yet documented the entire span of his life.

There was also the challenge of forming a sense of what made Plant tick and drove him on. To the casual observer he might seem garrulous, but beyond this front he is guarded and private, careful never to reveal too much of himself. I wanted to reach the man behind the music, since gaining a better understanding of him would shed new light on the road he has travelled.

As he sat in the Marathon Bar collecting his thoughts that December night, the hours running to morning, did he reflect upon how far he had come and how long he had journeyed? Upon the years of struggle, the fights with his parents, when there was no money in his pocket and he had sensed the dream that had driven him slipping from reach. Upon the soaring heights to which Led Zeppelin had taken him, when he had basked in the adulation of millions and felt the heady rush of that band’s power pumping through his veins. And on into the deep, black depths into which he had sunk, when there had been nothing to fill the empty spaces in his heart.

Through it all there had been music. It was, then and now, the thing that most lit him up. First it came crackling over the radio waves, then as something wild and primal from within. All the endless possibilities it promised had made his head spin. So often and so much he had been stirred by Elvis Presley and Robert Johnson, by sounds that rushed to him from the American West and the north of Africa. It had, all of it, carried him along. It had given him more than he could have dared to ask for and he had taken every last drop of it. And as he did so it had exacted from him a heavy and terrible price.

And in looking back, did he also turn to contemplating his present and on then to what might lie over the horizon? Raising Sand, of which he was so proud, had awoken something new within him, but there was the question of what to do next, of where to roam and with whom. This relentless curiosity at all that could be was something he had never lost. Even on this night, when he had puffed out his chest and swaggered back into the past, what sustained him most was the sensation of forward motion, of new frontiers and the mysteries held within.

‘You can never have a life plan if you’re going to be addicted to music,’ he told me when I had asked him about such things. ‘At this age, when you find you’re still getting goosebumps and a lump in the throat when you hear it, how can you tell how it’s ever going to go?’