Читать книгу Robert Plant: A Life: The Biography - Paul Rees - Страница 7

Оглавление

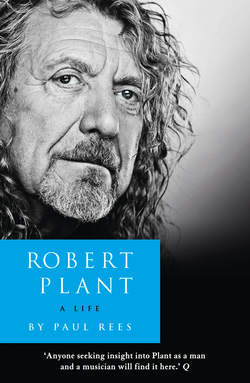

Bloody hell, Rob did a fantastic Elvis impression.

Robert Anthony Plant was born on 20 August 1948 in West Bromwich, in the heart of England’s industrial Midlands. His parents were among the first to benefit from the new National Health Service – the grand vision for a system of universal free health care set out by Clement Attlee’s Labour government upon coming to power in 1945 that had been made a reality the month before their son’s birth.

Plant’s father was also named Robert, like his father before him. A qualified civil engineer, he had served in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. Before the war he had been a keen violinist but the responsibilities of providing for his family took precedence over such things when he returned home. He retained, however, a love of classical music. His other great passion was cycling and he would often compete in local road races. He was by all accounts a decent, straightforward man, no more or less conservative in his outlook than other fathers of the time.

Father and son found a shared bond in football. Plant was five years old when his father first took him to see a local professional team, Wolverhampton Wanderers. Sitting on his dad’s knee he watched as the players came out from the dressing rooms and onto the brilliant green pitch, those from Wolves in their gold and black strip, and felt euphoric as the noise of the thousands-strong crowd consumed him. His father told him that Billy Wright, the Wolves and England captain, had waved up to him as he emerged from the tunnel that day.

His mother was Annie, although people often called her by her middle name, Celia. Like most households then, it was she who ran the home and put food on the table. Plant would inherit his mother’s laugh, a delighted chuckle. She called him ‘my little scoundrel’. The Plants were Catholics and raised their son within the strictures of their religion. Later on they would have a second child – a daughter, Alison. But Robert was to be their only son, and as such it was he who was the receptacle of all their initial hopes and dreams.

From an early age, Plant can remember music being brought into the family home. His grandfather had founded a works brass band in West Bromwich and was accomplished on the trombone, fiddle and piano.

‘My great-grandfather was a brass bandsman, too,’ he told me. ‘So everybody played. My dad could play, but never did. That whole idea of sitting around the hearth and playing together had gone by his generation. He went to war, lost his opportunities, and had to come home and dig deep to get them back, like so many men of the time.’

The town in which the young Plant spent his first years was two miles by road from the sprawling conurbation of Birmingham, England’s second city. Locals called the regions to the north and west of Birmingham the Black Country. This was on account of the choking smoke that had belched out from the thousands of factory chimneys that sprung up there during Britain’s industrial revolution of the 19th century. Writing of these acrid emissions in The Old Curiosity Shop, Charles Dickens described how they ‘poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light and made foul the melancholy air’.

By 1830 the Black Country’s 130 square miles had been transformed into an almost entirely industrial landscape of mines, foundries and factories, a consequence of sitting upon the thickest coal seam in the country. The rush to heavy industry brought not just bricks and mortar, but also the creation of new canal and rail networks, enabling the Black Country to export its mineral wealth to the far-flung corners of the British Empire.

They were still hewing coal out of the Black Country earth in the 1950s, although the glory days of the mines had passed. Iron and steel were worked intensively in local factories until the 1980s, glass to this day. The anchors and chains for the RMS Titanic’s first – and last – voyage of 1912 were forged in the Black Country town of Netherton, and the ship’s glass and crystal stemware was fired and moulded in the glassworks of nearby Stourbridge.

In keeping with their austere beginnings the people of the Black Country pride themselves on being hard workers; tough and durable, they tend in general towards a stoical disposition and a droll sense of humour. Their particular dialect, which survives to this day, has its roots in the earliest examples of spoken English and is often impenetrable to outsiders. Habitually spoken in a singsong voice it conveys nothing so much as amusement and bemusement. There is an old saying around these parts: ‘Black Country born, Black Country bred, strong in the arm and thick in the head.’ This was how they went out into the world.

Two of the most prolific gunfighters of the Wild West, Wes Hardin and ‘Bad’ Roy Hill, who between them killed seventy men, had their roots in the Black Country town of Lye, their families leaving from there for the promised land of America and their own subsequent infamy. The ancestors of Wyatt Earp, the Wild West’s great lawman who wrote his name into history at the O.K. Corral in 1881, hailed from Walsall, less than four miles from where Plant took his first steps.

When the Second World War came the region was inextricably tied to it. Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister at the time of its outbreak who had misguidedly attempted to appease Adolf Hitler, was born into one of Birmingham’s great political dynasties. Although the war was eventually won, its after-effects lingered on into the following decade. The rationing of foodstuffs such as meat and dairy continued in Britain until 1954. At the time of Plant’s childhood, West Bromwich and the Black Country, like so many of the country’s towns and cities, still bore the scars from six years of conflict. As a centre for the manufacture of munitions the area had been a prime target for German bombs. Throughout Birmingham and the Black Country were the shells of buildings and houses blasted into ruin. It was an everyday occurrence to find the tail end of bombs or shards of shrapnel littering the streets.

‘The whole area was still pretty much a bomb site in the early 1950s,’ recalls Trevor Burton, who grew up in Aston to the north-east of Birmingham’s city centre, and who would later cross paths with Plant on the local music scene of the 1960s. ‘The bomb sites, these piles of rubble and blown-out houses, they were our playgrounds.’

The 1950s would bring great change to Britain. At the start of the decade few Britons owned a TV set; those who did had just one channel to watch – in black and white. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on 2 June 1953 led to an upsurge in TV ownership and by the end of the decade 75 per cent of British homes had a set. The ’50s also witnessed the opening of Britain’s first motorways – the M6 in 1958 and the M1 in 1959 – establishing faster, more direct road links between cities such as London, Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester. Such progress brought the world closer to Britain, making it appear more accessible.

Yet at the same time Britain’s role on the global stage was diminishing. The Suez Crisis of 1956, during which Britain tried and failed to seize back control of the Suez Canal from Egypt, hastened the end of Empire. The United States and the Soviet Union were the new superpowers, Britain being relegated to the role of junior partner to the Americans in the decades-long Cold War that was to unfold between those two nations.

The national mood in Britain, however, was one of relief at the end of the war in Europe and of hope for better times. This began to be realised from the middle of the decade, by which time the nation’s economy was booming and wages for skilled labour were increasing. A rush by the British to be socially upwardly mobile left a void for unskilled workers that was filled by successive governments with immigrant labour from the Commonwealth. With these workers populating its steel mills and foundries – and now its car plants, too – Birmingham and the Black Country soon ranked among the country’s most multi-cultural areas. To the already healthy Irish population in Birmingham there would be added vibrant communities drawn from the Caribbean, India and Pakistan.

In 1957, so pronounced was the collective sense of affluence and aspiration that Harold Macmillan, the Conservative prime minister, predicted an unprecedented age of prosperity for the country. ‘Let us be frank about it,’ he said, ‘most of our people have never had it so good.’ The British people agreed and elected Macmillan to a second term of office in October 1959.

The Plant family embodied the rise of the middle classes in Macmillan’s Britain. As a skilled worker, Robert Plant Sr could soon afford to move his wife and son out from West Bromwich to the greener fringes of the Black Country. They came to leafy Hayley Green, a well-heeled suburban enclave located fifteen miles from the centre of Birmingham.

Their new home was at 64 Causey Farm Road, on a wide street of sturdy pre-war houses just off the main road between Birmingham and the satellite town of Kidderminster. It was a neighbourhood of traditional values and twitching net curtains, populated by white-collar workers. Unlike West Bromwich, it was surrounded by countryside. Farmland was abundant, the Wyre Forest close by and Hayley Green itself backed onto the Clent Hills.

Situated near the end of Causey Farm Road, number 64 was one of the more modest houses on the street. Built of red brick, it had a small drive and a garage, and from its neat back garden there was an uninterrupted view out to the rolling hills. For the young Plant there would have been many places to go off and explore: those hills, or the woods at the end of the road, or over the stiles and across the fields to the town of Stourbridge, with its bustling high street.

It was during this period that many of Plant’s lifelong passions were first fired. The Clent Hills and their surrounding towns and villages were the inspiration for the landscape of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, the writer of The Lord of the Rings trilogy and The Hobbit having grown up in the area in the 1890s. Plant devoured Tolkien’s books as a child, and time and again in later life would reference the author’s fantastical world in his lyrics.

In the summer the Plants, like so many other Black Country families of the time, would drive west for their holidays, crossing the border into Wales. They would head for Snowdonia National Park, 823 square miles of rugged uplands in the far north-west of the country. It was an area rich in Celtic folklore and history, and this, together with the wildness of the terrain, captivated the young Plant.

He was entranced by such Welsh myths as those that swirled around the mountain Cadair Idris, a brooding edifice at the southern edge of Snowdonia near the small market town of Machynlleth, which the Plants would often visit. It was said that the mountain was both the seat of King Arthur’s kingdom and that of the giant Idris, who used it as a place of rest from which he would sit and gaze up at the evening stars. According to legend anyone who sleeps the night on the slopes of Cadair Idris is destined to wake the next morning as either a poet or a madman.

At Machynlleth Plant learnt of the exploits of the man who would become his great folk hero, the Welsh king Owain Glyndŵr. It was in the town that Glyndŵr founded the first Welsh parliament in 1404, after leading an armed rebellion against the occupying English forces of King Henry IV. The uprising was crushed five years later, and Glyndŵr’s wife and two of his daughters were sent to their deaths in the Tower of London. Glyndŵr himself escaped capture, fighting on until his death in 1416.

But for Plant there would be nothing to match the impact that rock ’n’ roll was to have upon him as a child. Like every other kid who grew up in post-war Britain he would have been aware of an almost suffocating sense of primness and propriety. Children were taught to respect their elders and betters. In both the way they dressed and were expected to behave they were moulded to be very much like smaller versions of their parents. Authority was not to be questioned and conformity was the norm.

The musical landscape of Britain in the ’50s was similarly lacking in generational diversity. Variety shows, the big swing bands and communal dances were popular with old and young alike. As that decade rolled into the next, the country’s clubs heaved to the sounds of trad jazz, making stars of such bandleaders as Chris Barber, Acker Bilk and Kenny Ball, who played music that was as cosy and unthreatening as the social mores of the time. In the United States, however, a cultural firestorm was brewing.

Elvis Presley, young and full of spunk, released his first recording on the Memphis label Sun Records in the summer of 1954. It was called ‘That’s All Right’, and it gave birth to a new sound. A bastardisation of the traditional blues songs of black African-Americans and the country music of their white counterparts, rock ’n’ roll was loud, brash and impossibly exciting – and it arrived like an earthquake, the tremors from which reverberated across the Atlantic. Behind Elvis came Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, Gene Vincent and others, all young men with fire in their bellies and, often as not, a mad, bad glint in their eyes.

In 1956 the mere act of Elvis swivelling his hips on TV’s Ed Sullivan Show was enough to shock America’s moral guardians. It was also instrumental in opening up the first real generational divide on either side of the Atlantic. Elvis’s gyrations acted as a rallying point for both British and American teenagers, and as an affront to their parents’ sense of moral decency.

In the English Midlands rock ’n’ roll first arrived in person in the form of Bill Haley. In 1954 Haley, who hailed from Michigan, released one of the first rock ’n’ roll singles, ‘Rock Around the Clock’. He followed it with an even bigger hit, ‘Shake, Rattle and Roll’. When, on his first British tour, he arrived at Birmingham Odeon in February 1957 the city’s teenagers queued all around the block for tickets. At the show itself they leapt out of their seats and danced wildly in the aisles. It mattered not one bit that, in the flesh, Haley had none of Elvis’s youthful virility.

Laurie Hornsby, a music historian from Birmingham, recalls: ‘The man who was responsible for going down to Southampton docks to meet Haley off the ship was Tony Hall, who was the promotions man for Decca Records in London. He told me that he stood there at the bottom of the ship’s gangplank, and down came this old-age pensioner hanging onto his hair for grim death. Hall thought, “My God, I’ve got to sell this to the British teenager.” But sell it he did.’

By the time Elvis burst onto the scene Plant was a primary-school boy. Tall for his age, he was blessed with good looks and a pile of wavy, blond hair. He might have been too young to grasp the precise nature of Elvis’s raw sex appeal but he was immediately drawn in by the untamed edge to his voice and the jungle beat of his music. From the age of nine he would hide himself behind the sofa in the front room at 64 Causey Farm Road and mime to Elvis’s records on the radio, a hairbrush taking the place of a microphone.

He soon progressed to the songs of Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. Each weekend he and his parents would gather around the TV set to watch the variety show Sunday Night at the London Palladium, and it was on this, in the spring of 1958, that the ten-year-old Plant first saw Buddy Holly & the Crickets. That year Holly also came to the Midlands, playing at Wolverhampton’s Gaumont Cinema on 7 March and, three days later, giving an early and later evening performance at Birmingham Town Hall.

By then Plant had begun to comb his hair into something that approximated Elvis’s and Cochran’s quiffs, much to the chagrin of his parents. He was also digesting the other sound then sweeping the UK, one that made the act of getting up and making music seem so much more attainable. Its roots lay in the African-American musical culture of the early 20th century – in jazz and blues. In the 1920s jug bands had sprung up in America’s southern states, so called because of their use of jugs and other homemade instruments. This music was revived thirty years later in Britain and given the name ‘skiffle’.

Britain’s undisputed King of Skiffle was Lonnie Donegan, a Glaswegian by birth who had begun playing in trad jazz bands in the early ’50s. Having taught himself to play banjo, Donegan formed a skiffle group that used cheap acoustic guitars, a washboard and a tea-chest bass. They performed American folk songs by the likes of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly. Starting in 1955 with a speeded-up version of Leadbelly’s ‘Rock Island Line’, Donegan would go on to have twenty-four consecutive Top 30 hits in the UK, an unbroken run that stretched into the early ’60s.

Donegan’s success, and the simplicity of his set-up, prompted scores of British kids to form their own skiffle groups. One of these, the Quarrymen, was brought together in Liverpool in the spring of 1957 by the sixteen-year-old John Lennon. For his part, Plant was still too young and green to even contemplate forming a band. But in skiffle, as in rock ’n’ roll, he had located a route back to black America’s folk music, the blues. It was one he would soon follow with the tenacity of a pilgrim.

The thing that Plant thought about most on the morning of 10 September 1959, however, was not music but how little he liked his new school uniform. There he stood before his admiring mother dressed in short, grey trousers and long, grey socks, a white shirt, a red and green striped tie and green blazer, with a green cap flattening down his sculpted hair. At the age of eleven, and having passed his entrance exams, he was off to grammar school.

But not just to any grammar school. Plant had secured a place at King Edward VI Grammar School for Boys in Stourbridge, which had a reputation for being the best in the area. For his parents, his attending such an establishment would incur extra expense but would also impress the neighbours. The school had been founded in 1430 as the Chantry School of Holy Trinity and counted among its alumni the 18th-century writer Samuel Johnson. A boys-only school of 750 students, it was so steeped in tradition that first years were introduced in the school newspaper beneath the Latin heading salvete, the word used in ancient Rome to welcome a group of people.

On that first morning Plant and ninety or so other new arrivals were lined up outside the staff house in the school playground. Surrounding them were buildings of red brick, including the library with its vaulted ceilings and stained-glass windows. The masters in their black gowns and mortarboards came out and assigned each of them to one of three forms. Those boys who had excelled in their entrance exams and were considered to be future university candidates were gathered together in 1C. Plant was placed in the middle form, 1B.

The school operated a strict disciplinary code, one that was presided over by the headmaster, Richard Chambers. A tall man who wore horn-rimmed glasses, Chambers had a hooked nose that led students to christen him ‘The Beak’. Behind his back he was also mocked for a speech defect that prevented him from correctly pronouncing the letter ‘r’. But Chambers mostly engendered both respect and fear.

‘He was extremely strict, a sadist really,’ recalls Michael Richards, a fellow student of Plant’s. ‘If you got into trouble, he would call your name out in assembly in front of the whole school. You would have to go and stand outside his office, and eventually would be called in. He would reprimand you for whatever you’d done and then whack you across the backside four times with a cane. Then he’d tell you to come back after school. So you’d have all day to think about it and then you’d get the same again.’

In many respects Plant was, to begin with at least, a typical grammar-school boy. He collected stamps and during the winter months played rugby. Although the school did not play his beloved football – indeed footballs were banned from the playground – he would join groups of other boys in kicking a tennis ball about at break times, using their blazers as makeshift goalposts. In his second year he was nominated as 2B’s form monitor by his tutor, a role that gave him the giddy responsibilities of cleaning the blackboard and trooping along to the staff room to notify the other masters if a tutor failed to arrive for a lesson.

What marked him apart was his love of music and the manner in which he carried himself. Going about the school he would typically have a set of vinyl records tucked under his arm – and these, often as not, would be Elvis Presley records. He even took to imitating Elvis’s pigeon-toed walk.

‘Bloody hell, Rob did a fantastic Elvis impression,’ says Gary Tolley, who sat next to Plant in their form. ‘He was Elvis-crazy, but early Elvis, not the Elvis of G.I. Blues, when he’d started to go a bit showbiz. He was very into Eddie Cochran, too. He had the same quiff. When you see all those pictures of Cochran looking out from the side of his eyes at the camera, that was Robert.’

Plant and Tolley, who was learning to play the guitar, soon became part of a clique at school that was based around their shared interest in music. Their number included another classmate, Paul Baggott, and John Dudley, a budding drummer. They prided themselves on being the first to know what the hot new records were and when the likes of Cochran or Gene Vincent would be coming to perform in the area.

‘Not blowing our own trumpets, but we were all popular at school,’ recalls Dudley. ‘The other kids sort of looked up to us, because we knew a little bit that they didn’t. Robert was a nice guy, but a bit full of himself. He was quite cocky. He’s always been like that. The Teddy Boy era had died by then, but he made sure that he’d got the long drape coat and the lot. A lot of people thought he was arrogant because he’d got that sort of body language about him.’

‘Rob was very good looking and he always seemed to be at the centre of whatever was going on,’ adds Tolley. ‘He had something. Charisma, I suppose. In those days, the Catholics would have a separate morning service to everybody else and then come in to join us for assembly. Robert would walk into the main hall with his quiff and his collar turned up, and you could see all the masters and prefects glaring at him. He wore the school uniform but somehow he never looked quite the same as everybody else.’

Plant and Tolley would become good friends. Outside of school they went to the local youth club to play table tennis or billiards, and Plant would bring along his Elvis and Eddie Cochran singles to put on the club’s turntable. Plant had also picked up his father’s love of cycling, and he and Tolley would go off riding around the Midlands on a couple of stripped-down racing bikes.

‘Robert’s dad knew someone at the local cycling club and I can remember going to a velodrome near Stourbridge with Rob, riding round and round it and thinking we were fantastic,’ says Tolley. ‘He’d come to my house a lot and always turn up at mealtimes. If we were going out cycling for the evening, he’d arrive forty-five minutes before we’d arranged. Inevitably, my mum would say, “There’s a bit of tea spare, Robert. Would you like it?” “Oh, yes please, Mrs Tolley.”’

‘He’d be round our house for Sunday tea,’ says John Dudley. ‘He was always very polite. He’d ask my mum for jam sandwiches. If you’re going to put people into a class, his mum and dad were a class above mine. My father worked on the railways. I believe Rob’s father by then was an architect. They lived in a better house than we did. Rob was never from anywhere near an impoverished background.’

For as long as their son maintained his academic studies Plant’s parents tolerated his love of rock ’n’ roll, although his father, who mostly listened to Beethoven at home, professed to being mystified by it. In 1960 they bought him his first record player, a red and cream Dansette Conquest Auto. When he opened it he found on the turntable a single, ‘Dreaming’, by the American rockabilly singer Johnny Burnette. With his first record token he bought the Miracles’ effervescent soul standard ‘Shop Around’, which had given Berry Gordy’s nascent Motown label their breakthrough hit in the US.

A future was beginning to open out for the eleven-year-old Plant. It was one now free from the spectre of being required to spend two years in the armed forces upon leaving school, Macmillan’s government having abolished compulsory National Service that year. It did, nonetheless, still lie beyond his grasp, as was emphasised when his mother insisted he trim his quiff and he glumly complied.