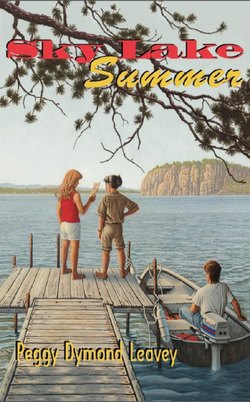

Читать книгу Sky Lake Summer - Peggy Dymond Leavey - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1998

ОглавлениеWhen she got on the four o’clock bus for Sky Lake, Jane Covington had already made up her mind that she was not going to talk to anyone. Her bad mood, which resulted from another early morning argument with her mother, still hovered in the back of her mind like some dark-winged bird. Right up to the last minute she had hoped her mother would change her mind, and for a change let her spend the summer in the city.

“I don’t see why Nell can’t come here for once, if you’re that worried about her being alone,” Jane had grumbled. “Besides, I really wanted to visit Dad this summer.”

Mary Covington, who was fitting newly-washed pairs of socks, like so many dinner rolls into Jane’s dresser drawer, had paused for a moment. “And is that convenient with your father?” she had asked, in that see-how-well-controlled-I-am tone of voice she used whenever the two of them talked about Dan, Mary’s ex-husband.

Jane had fallen back on her bed, expelling air from her lungs loudly and looking up at the ceiling. “I don’t know. He hasn’t asked me yet, but I want to be here when he calls. And I won’t be if I have to spend the whole summer up at Nell’s.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake, Jane!” Mary had sputtered. “It’s not for the whole summer.” She had wedged in the last pair of socks and slammed the drawer shut. “I said for the month of July.”

Jane had closed her eyes.

When someone drifted onto the empty seat beside her on the bus, Jane deliberately opened her book, sneaking only a brief peek at the reflection in the window. The bus driver pushed the passenger’s carry-on luggage onto the shelf over their heads and promised to let her know when they had reached Sky Lake. “This young lady’s getting off there too,” he said.

Shifting over towards the window, Jane took another look in the tinted glass. In spite of the heat of early July, the woman was dressed in something long and flowing, gauzy, with flowers and numerous scarves. Her voluminous hair, which was neither blonde nor white, floated around her head like soft clouds. It was hard to tell from the window how old she was. Older than Mary, who had turned forty last week; closer perhaps to the age of her grandmother, Nell. To Jane’s relief the woman did not want to talk and settled her head against the back of the seat with a sigh.

Shortly, the bus left the heavy traffic of the four-lane highway behind and turned north, away from the acres of car dealerships with their fluttering neon pennants, and into the rolling countryside where farms stretched out on either side.

As the miles disappeared under the wheels of the bus, Jane felt her heavy mood gradually lifting. There would still be the month of August left when she got home. And remembering the freedom she enjoyed at Nell’s cottage brought an involuntary smile to her lips. It wouldn’t be so bad. At My Blue Heaven she could sleep late, read all day if she felt like it and swim whenever she wanted to, within reason. Or do absolutely nothing at all. And Nell never reminded her that she really should be watching what she ate. Why, she was still a growing girl!

“I dreamed about coming here last night.” The voice beside her startled Jane. “I believe in dreams, don’t you?” the woman asked, smiling expectantly.

“Not really,” Jane admitted, closing her book but keeping one finger in it to mark her place. “I never really thought about it.”

“Oh, yes,” the woman continued, “I believe dreams are meant to connect us somehow. Connect us to some other person, some other time perhaps.”

Jane thought about this for a moment. It was an intriguing idea.

“My name’s Mimosa,” the woman said, turning in her seat and offering Jane a slim, cool hand. “Mimosa Granger. But everyone just calls me Mim.” Her voice was soft and lilting, reminding Jane of music, or water running over stones. Maybe the woman was some sort of mystic. She certainly looked the part, with her loose garments and long, delicate neck. And ever since she had taken the seat beside her, Jane had been aware of the fragrance of flowers in the air. Was it roses? Lilies-of-the-valley? Something delicate, spring-like.

Mim wanted to know all about Sky Lake, and Jane, who had spent part of every summer there since she was eight, found herself describing it with growing enthusiasm. “And just wait till you see the big rock,” she promised. “It’s so high, it’s amazing.”

“It all sounds quite lovely,” Mim agreed when Jane finally wound down. Ms. Granger had inherited a piece of property on the lake and was going up to take a look at it. “And then, most likely, I’ll arrange to sell it,” she said, playing with the ends of one of her scarves. “I could have done everything from back home in Massachusetts, but seeing as it’s summer and I’m not tied to a job anymore, or to my poor old mother, God rest her soul. Not that ‘tied to’ is the right word, but I did look after her all those years.”

“We’re lucky, I guess,” said Jane. “My grandmother doesn’t need looking after. ’Though Mom feels better knowing I’m with her for part of the summer. Nell, that’s what we all call her, goes up to My Blue Heaven every year at the end of May, and she stays right through till late October.”

“My Blue Heaven on Sky Lake,” Mim smiled. “How quaint.”

“It’s named after a song my grandparents liked,” said Jane.

The bus was traveling now through a varied landscape, rocky terrain dotted with white birch. There were low-lying swamps at either hand, filled with the skeletons of drowned trees and sudden glimpses of lakes in the distance. When the familiar procession of roadside stands that sold home-baked treats and promised blueberries in season began, Jane knew they were nearing their destination.

The bus made the final turn into the dusty parking lot at the Sky Lake Marina, and Jane spotted Nell right away. She was fanning herself with her straw hat and talking to the boy who was filling her car with gas. Nell talked to everyone.

“She’s got her car,” Jane said, waiting for Mim to gather her floating scarves and get to her feet. “We can give you a ride to the place you’re staying.”

Once they were on solid ground, the driver cranked the door shut, and the three stepped clear of the fumes as the bus lumbered off. Jane introduced her grandmother to Mimosa Granger, Nell repeating Jane’s invitation of a lift to her accommodations.

Mim eyed Nell’s car with trepidation. It had so many dents and scrapes, such an accumulation of dirt, that it was hard to say what colour it had been. Mud colour, kind of. There were bits of loose chrome and rusted metal hanging off it everywhere, making it a challenge to get into it without tearing something. Nell called it the Lake Car. Back home in the city she used public transit.

“It’s really no bother at all, Miss Granger,” Nell insisted, misinterpreting Mim’s hesitancy. “We go right past the Bide-a-Wee cabins.”

Having no alternative, unless she wanted to wait for a taxi to come from the village out on the highway, Mim climbed into the back seat and sat with her bag clutched in both hands. They took off in a cloud of yellow dust, fishtailing their way to the top of the hill, Nell practically standing on the accelerator in order to force the car though the fresh gravel on the road. When they had crested the hill and started down the other side, Nell gave Jane a satisfied smile.

They dropped Mim off at the tourist cabins, and Nell refused to pull out of the driveway until Mim’s wave from the door of the office indicated that her cabin was indeed ready.

Then began the final ascent, the road climbing above the roofs of cottages, the waters of Sky Lake dropping further below them on the left. It was all so familiar, it was like coming home. Jane smiled to herself, remembering the first time she’d come to Nell’s summer place, how she’d wakened one night to the sound of music and had discovered her grandmother downstairs, dancing, swirling to the music, the hem of her skirt in either hand, a look of utter happiness on her face.

After witnessing that, Jane would amuse the two of them by inventing exotic past-lives for her grandmother. Surely, Nell Van Tassell had been a famous ballerina who had fled to this country to escape a corrupt government, or was the widow of exiled royalty, or a gypsy princess, even. In truth, she was just Nell, the widow of a man who used to sell farm equipment, but someone who had always been there for Jane.

“You still dancing, Nell?” Jane asked. Afternoon sunlight flickered through the trees as they passed.

“Every time the spirit moves me,” Nell replied, gripping the steering wheel in front of her narrow chest and concentrating on the next curve in the road.

My Blue Heaven was at the end of the road. Just when Jane was sure the car was about to go slamming into the black and yellow checkered sign on the rock dead ahead, Nell yanked on the wheel and whipped the car to the left, coming to an abrupt halt at the back door of the cottage.

“We’re here!” Nell announced, adjusting her hat back onto her head and looking as surprised as Jane to have survived the journey. And then, “Oh, I’m so glad you came, Janey.” She put a hand on the back of Jane’s neck and pulled her close.

“Didn’t you think I would?”

“Well, I know how it is with teenagers. And you turned thirteen this year, didn’t you? I wouldn’t have been surprised if you had decided to stay home with your friends.”

“You know me better than anyone,” Jane admitted, undoing her seat belt and trying in vain to get it to rewind. “Actually, Mom and I did have a fight about it. But now that I’m here, I know I’d miss this place if I didn’t come for at least part of the summer. And you too, of course.” Jane planted a kiss on the soft cheek before reaching for her knapsack.

Stepping out of the car, she was met by a familiar scent, the fragrance of warm grass and wild daisies, the earthy smell of moss and trees and old wood. She took a deep breath and was truly glad to be back. “Come on,” she said. “I want to check things out. See what you’ve been up to while I’ve been gone.”

Among the rituals the two of them performed each summer, putting the dock into the water was usually the first. Together they would wheel it down to the shore, digging in their heels to hold it back against the incline, and then finally heaving it out so that it met the water with a tremendous smack.

This year it was already in place, the old row boat tied to one of the rusty pipes at the end. Jane dropped the knapsack by the back door and jog-trotted down the slope to make sure she wasn’t seeing things.

“You didn’t wheel that dock down here all by yourself, did you?”

“Oh, no,” Nell assured her as the two of them stepped onto the bleached boards, which rocked and bobbed under their weight. “I’ve got the nicest young fellow helping me out with odd jobs this year. All I have to do is let him know I need a hand, and over he comes in his boat. Jesse’s a lovely boy.”

Nell had never needed anyone to do odd jobs before, and that caused Jane to look a little more closely at the small woman beside her. “You feeling all right, Grandma?” she asked. The clear blue eyes still held the same sparkle, the pale skin under the braided crown of white hair didn’t look any different. She had never thought much about Nell getting older, and she wasn’t sure she liked the idea of some stranger doing the things she used to do for her.

“I’m perfectly fine, dear heart,” said Nell. “And thank you for asking. Now, let’s go up. I made us some lemonade before I went to fetch you.”

My Blue Heaven was long past needing a coat of paint, being now more silver than blue. It seemed to Jane that every year it settled more comfortably into its surroundings. The rocks, with their embroidery of lichen, nestled against its stout foundation, and the feathery pines spread their branches to draw it more closely under their shelter.

A screened-in porch extended around the front and east side of the cottage. It was more like an outdoor living room, a shady space filled with small tables, piles of ancient books and magazines, mismatched lamps and pieces of old wicker furniture with fraying cushions. It had a throat-biting, musty smell to it. On days when the wind drew cool rain up from the lake, they could close the French doors to the porch and keep the bad weather out.

Jane awoke on her first morning at Sky Lake to find sunlight flooding her upstairs room. From below came the comforting sounds of her grandmother moving about, closing windows against the chill of the new morning, lifting the lids of the cookstove. Jane snuggled deeper into the bed again, pulling the comforter up to her ears. Nell, she knew, would be making breakfast—oatmeal porridge with lots of brown sugar, a stack of golden toast, and fruit jam made right there in the kitchen of My Blue Heaven.

Downstairs, the phone was ringing. Throwing off the bed covers, Jane dragged a pair of sweat pants and a shirt out of her knapsack, knowing it wouldn’t be long before she could exchange it for shorts and a T-shirt. She pulled the brush through her thick, blonde hair and thudded down the stairs and into the kitchen. The oatmeal was erupting in little volcanoes in a battered pot on the back of the stove.

Mrs. McPherson, the egg lady, had called to remind Nell that she had three dozen brown eggs set aside for them. “I clean forgot when I went to fetch you yesterday,” Nell said, handing Jane a knife to butter the toast.

They drove around the lake to pick up the eggs before noon, and Jane left the two women chatting in the pungent warmth of the McPhersons’ back kitchen to tramp the short distance down to the marina store. The tinkle of the bell over the door announced her arrival.

She was the only customer, and the man behind the counter waited while she made her selection, then folded down the top of the small paper bag, leaving a pocket of air in the bottom with the raspberry jujubes—as though she’d bought a whole dollar’s worth instead of just nine cents, the change she got back from the can of pop.

“Here for the holidays?” the shopkeeper asked, smiling.

Jane nodded, her mouth full of gummy candy.

“You’re Mary Van Tassell’s girl, aren’t you? I haven’t seen Mary in years. What’s she up to these days?”

“My mother?” Jane’s teeth had come unstuck. “She’s selling real estate.” She wasn’t sure she should be telling this person these things. This tall, spare man with the thinning, foxy-coloured hair was not the shopkeeper she remembered from other summers.

“You say hi to your mother for me. Jackson Howard’s the name. She’ll remember.”

“I’ll tell her,” said Jane, easing the door open.

She retraced her steps up the road, past the new municipal centre which had been under construction a year ago. A teenaged boy with a bandanna tied over his hair was crouched in the long grass, painting the lower part of the fence around the new building. His bare back was tanned from the sun. He stood up when Jane drew level with him and wiped the back of his neck with a paint rag. In his leather workboots, he was about the same height as she was, although she judged him to be a couple of years older. She had towered over most of the boys her own age since sixth grade.

“Hi,” Jane said.

If he returned the greeting, Jane didn’t hear him. “There’s a library in this building, isn’t there?” she asked after a few awkward seconds.

“You can’t take drinks in there,” the boy said, a scowl spoiling his dark good looks.

“I wasn’t going in now. Just wondering if they were open.”

“At three,” he said, and hunkered down again onto the tops of his boots, pulling the grass away from the fence and reaching for his brush.

There was no sign of activity up the road at McPherson’s yet, so Jane followed the sidewalk around to the front of the building which faced the lake. Two long tables had been set up in the shade, and these were filled with old books for sale, showing various degrees of wear. She moved along one table where paperbacks had been set, spine side up, in long, ragged rows.

“Quarter apiece.” The boy had come around from the other side.

“I’m just looking,” Jane said.

“Well, I’m in charge,” the boy informed her. “You want anything, just give the money to me.”

Jane spent several minutes bent over the titles on the rows of spines in front of her. They were mostly old westerns or romances, nothing that interested her.

“What about these?” she asked, indicating some cartons underneath the table. She squatted on her heels and opened the flaps on one of the boxes.

“Hardcovers,” said the boy. “Buck a piece. You Ms. Van Tassell’s granddaughter?”

“That’s right.”

“She said you were coming this week.”

“And you are?”

“Jess Howard.”

Nell’s handyman. “Hi,” Jane said, trying the smile again. “I’m Jane Covington.”

“I figured,” the boy said.

Jane wondered if she might have red jujubes stuck to her front teeth. She drew one of the books out of the box, a small, blue volume with gold lettering on the cover. The Sea and the Jungle, by H. M. Tomlinson.

She flipped idly through it, knowing it too wasn’t anything she’d want to buy, and wondered how long it would be before Jess Howard got tired of his surveillance. Suddenly, a piece of folded paper fell out of the pages of the book and fluttered onto the grass. She picked it up and unfolded it carefully. It was a handwritten letter and Jane read it, crouched over the carton of books.

“That’s funny,” she said as she stood up, frowning. “Look what was in this book.”

Jesse’s eyes passed quickly over it before he handed it back with a shrug.

General Delivery,

Sky Lake, Ontario, Canada.

September 7, 1930

Dear Madam:

I feel a bit of a fool asking you to help us. I’m afraid I don’t even know your name. But you had such a kind face when you waited on me, and you smiled at my baby before we left your shop and got into the boat. I could think of no one else to turn to.

I think we may be in danger. My husband’s brother is quite unwell. He has such terrible rages. I never would have come here had I known his true condition. I fear he may be losing his mind.

Yours,

Eugenie G. Fraser

(Mrs. Thos. Fraser)

“Someone’s old letter,” remarked Jess.

“I know,” said Jane. “But it’s more than that. Whoever Eugenie G. Fraser is, she says she thinks she’s in danger.”

“So?” said Jess.

“Doesn’t that bother you?”

Jess shrugged. “Not really.”

“But it sounds like she’s asking someone for help.”

“Maybe you didn’t notice the date,” Jess suggested, with sarcasm.

Jane leaned her backside against the table and re-read the letter. The paper it was written on was very thin, its folds pressed flat by the book and the weight of the years. “It sounds as if she’s afraid of her husband’s brother. I wonder where it came from, who Eugenie G. Fraser is.”

“By the return address, I’d say she was someone here on the lake,” Jess said, picking paint from his fingernails.

“And this book must have belonged to the person who got the letter,” Jane decided. “There’s no envelope. I wonder who it was.”

“The library gets donations like this all the time.” Jess waved an all-encompassing arm over the rows of books. “Most of the time they’re so old we can’t use them.”

“You work at the library?” Jane asked.

“Some of the time.”

“Well, the letter was written to someone who ran a shop,” Jane said, wrinkling her brow. “She says here, ‘when you waited on me’.”

“Could have been a waitress,” suggested Jess.

“Then she wouldn’t have said ‘your shop’. She says, ‘when we left your shop’ and ‘before we got into the boat’. So it sounds like the shop was by some water. It could even have been the store right here at the marina.”

“Could have been,” Jess allowed.

“Do you know who ran the store in 1930?”

Jess shook his head. “No idea.”

“I doubt if my grandmother would know either,” Jane said, doing the math in her head. “In 1930, she would have been, oh, just little. Doesn’t it make you the least bit curious about what happened to this poor woman?”

Jess’s look was non-committal. “You can’t just go and knock on her door after 68 years,” he said. “ ‘Hello Ma’am, are you still looking for help?’ ”

Jane decided to ignore the obvious. “We couldn’t find out which house she lived in anyway,” she pointed out. “General delivery means she picked up her mail at the post office.”

Jess scratched the back of his neck and shifted his weight restlessly. “It’s just an old letter. Probably someone was using it as a bookmark.”

“Maybe,” said Jane. He could be right. Perhaps she was making too much of it. “Look,” she decided. “I’ve got to go anyhow. My grandmother will be waiting for me. Maybe you should just give this to the librarian. We probably shouldn’t even have read it.”

“Whatever,” said Jess. Taking the folded paper from Jane, he poked it down into the pocket of his jeans. He followed her back around to the other side and bent to pick up his paint brush again.

“Nice to have met you,” said Jane. She didn’t expect a reply and didn’t get one. She could see Nell getting into her car at McPherson’s, and she quickened her pace before the vehicle came lurching down to meet her, spitting gravel and coughing dust onto the fresh paint.

She needn’t have worried. The Lake Car stalled before it reached the end of the driveway, and Jane seized the opportunity to clamber inside.

“I see you met young Jesse,” Nell smiled, gears grinding as they took off.

Jane opened the bag of candy and held it in Nell’s direction. “Do you know anyone named Fraser around here?” she asked.

Nell shook her head and waved the candy away. “Can’t say as I do. What did you think of Jesse Howard?”

“Weird name for a boy, if you ask me.”

“Not at all. It’s Biblical, in fact. Nice-looking young man, don’t you think?”

Nell’s car was awfully hot and the window on Jane’s side didn’t roll down any longer. “He’s okay,” Jane said. “Not exactly what I’d call friendly. Oh, the man at the store said to say hi to Mom.”

“Jackson Howard,” Nell nodded. “Man with his name on backwards.”

Jane blew into the empty bag and, holding it shut, burst it with a bang. “So you never heard of anyone named Fraser? Mrs. Thos. Fraser?”

“Why?” Nell asked, affording her a quick glance. “What’s this all about?”

“There was a book sale at the municipal centre,” Jane explained. “I was looking at some of the old books and a letter fell out of one of them. It was all folded up, from someone called Mrs. Thos. Fraser, and it was written in 1930.”

“Long time ago,” said Nell, craning forward to negotiate a curve in the road.

“I know, but the weird thing about this letter was that this Mrs. Thos. Fraser said she thought she was in danger, and she was writing to someone, asking for help.”

“What kind of danger?”

“I don’t know for sure. She said her husband’s brother had ‘terrible rages’. That she never would have come if she’d known.”

“My word! That does sound ominous,” Nell agreed.

“It was written to a woman who looked after a store, and the store was somewhere near water. I figured out that much. Maybe even the store here at the marina.”

“I’m not sure who would have had the store here, way back then,” said Nell. “It’s nice to see the Howards take it over now, though. Jackson’s been out west for years. He and Jesse came back just last fall.”

“Then Jess is his son?”

“That’s right.”

Jane looked at her watch, relieved that there would still be time for a swim before lunch. “I wonder what happened to Mrs. Thos. Fraser,” she mused, picking up one of the warm brown eggs which nestled in the container on the seat between them.

“Thos. is short for Thomas,” said Nell. “Mrs. Thomas Fraser.”

“Whatever,” said Jane, holding the egg to her cheek. “I’ll just call her Eugenie.”