Читать книгу Sky Lake Summer - Peggy Dymond Leavey - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеA steady rain greeted Jane her second morning at the cottage. All day it drifted, ghostlike, back and forth across the lake and sighed through the dismal trees. Jane spent most of the time reading, curled up under the lamp on one of the couches in the living room, listening to the rhythmic creak of Nell’s rocking chair, the intermittent popping of the fire in the cookstove, eventually falling asleep. When she awoke, stiff and chilled, she went to draw a chair up in the warmth of the kitchen where her grandmother was playing solitaire.

“I expect you needed that nap,” Nell said when Jane apologized for dropping off.

“Mom says I sleep too much,” Jane yawned. “She dragged me to the doctor, but I could have told her I wasn’t sick. Maybe I sleep to avoid arguing with her.”

“That’s too bad,” said Nell, counting out three more cards from the pile she held in her hand. “I expect it’s a stage you’re both going through.”

Jane stood up and stretched her arms above her head. “Mom doesn’t try to understand me anymore,” she stated flatly.

“Do you do the same for her?” asked Nell, looking up from the cards on the table.

“What’s to understand?”

“She hasn’t had an easy life, Jane.”

“Oh, you mean because of Dad? She’s the one who sent him away.”

Jane saw Nell bite her lip. “I think you know better, dear.”

Jane pretended to concentrate on the length of spider web strung between the little china figurines on the window sill, separating them one by one from its clutch. The worst thing she had ever heard Nell say about Dan Covington was that he was a man of little strength. ’Though Jane never knew what staying at a nine-to-five job had to do with a man’s strength. To Jane, her father was a man who dreamed dreams, a man who felt he had to follow them. Always sure that the next get-rich-quick scheme was the one that would do it for him, he had come and gone many times during Jane’s childhood, until finally Mary had suggested he leave altogether. But no one had ever bothered to ask Jane how she felt about it.

She is running, her mouth gasping for air, her legs pumping wildly. Her arms ache with the weight she is carrying. But no matter how hard she runs, she is slowly being drawn back towards a swirling vortex, back towards whatever it is that she is fleeing.

Jane awoke suddenly and sat up with a gasp, her pulse pounding. She had been dreaming. Realizing that was all it was, she lay down again, only to resume the tossing she’d started before the nightmare. She shouldn’t have spent so much time sleeping during the day, she decided. What was it the woman on the bus had said? That dreams are meant to connect you to something? She tried to recall the dream, to put together the pieces and think about what she might have been running from.

She was eating her cereal at the kitchen table the next morning, her book propped open in front of her, when Nell came back inside from the clothesline.

“Will you look at this?” Nell sounded exasperated. She set what looked like an ordinary red brick on top of the wood box inside the back door. “It’s not the first one to fall off the chimney. I absolutely must get some mortar and get it repaired.” She was already at the telephone, pressing buttons.

“Morning, Jackson. It’s Nell Van Tassell. Oh, fine, fine. Looks like a grand day. Yesterday’s rain was just what we needed.”

Jane closed her book and took her breakfast dishes to the sink. How hard was it to put two bricks back on a chimney anyway, she wondered? Outside, she discovered the day was warming up quickly. She swung herself into the old striped hammock which sagged between two poplar trees in the side yard, pushing herself off with one foot, swinging there, facing the lake where the sunlight glinted. She waited for Nell.

Today, they were going to take a picnic lunch and row over to the island, see what the crop of raspberries was going to be like this year. Of all the cottagers on the lake, Nell was the only one Jane knew who still considered a stout set of oars and muscles to match the best way to power a boat.

The screen door slammed and Nell came down the steps towards her. “It’s all set then,” she announced. “Jesse’s picking up some supplies and he’s going to fix the chimney for me. Right away. You don’t mind having our picnic here, do you, dear? We use that stove everyday, and the chimney is dangerous the way it is.”

Jane gave herself another push to set the hammock in motion again. “Jesse didn’t mind coming?”

“Well, I didn’t actually speak to him,” Nell admitted, dropping her hands into the pockets on the front of her denim skirt. “But when I asked his father about getting some mortar, Jackson said he’d send Jesse over to do the work for me. He’ll do some other little jobs while he’s here. What teenager doesn’t need a little extra money these days?”

Nell went back inside and Jane debated whether she should go for a swim first or putter about in the row boat for a while. The warmth of the sun was making her lazy. Maybe she would go and look for the raspberries herself. She would just as soon not be here when Jesse arrived, considering his surly attitude when they had first met. But she did wonder if he might have discovered anything more about the strange letter she’d found.

Jane had gone upstairs to straighten her room when she heard the sound of an outboard motor approaching. From the window, she saw Jess Howard pull his boat into the empty berth on the other side of the dock, get out, tie the boat to the pipe, and reach down for a paper sack, which he slung onto his shoulder. Then he strode with it up the incline to the cottage. The bandanna was gone from the dark hair, and he had added a white T-shirt to his wardrobe of jeans and workboots.

Jane heard Nell go out to greet him, and the sound of their voices moved around to the back. From the window at the head of the stairs, Jane watched as Jess entered the shed and came out with the ladder. He set it down on its side against the building. Reaching over his shoulder with one hand, she saw him pull his T-shirt off over his head and stuff it into the waist band at the back of his jeans. Then, before bending to pick up the ladder again, he looked directly up at the window. Jane stepped back quickly, feeling the colour rise in her face, knowing she’d been caught.

“Oh, there you are,” said Nell when Jane came down into the kitchen again. “Could you take Jesse this lemonade, dear?”

“Oh, Nell. He just got here! Couldn’t it wait?”

“It’s pretty hot around there on the east side, Jane. Jesse will be here for a while. He’s going to set the stones back in the front planters for me, do some other repairs. It wouldn’t hurt you to be a little more friendly, would it?”

“He didn’t act like he was looking for a friend,” Jane said. She took the glass without another word and found Jess on the far side of the cottage, mixing mortar in the old wheelbarrow. She wished now that Nell hadn’t made that remark about his looks the other day, and she especially wished that he hadn’t seen her watching him from the window on the stairs.

“My grandmother sent you some lemonade.”

“Thanks,” said Jess, without raising his head.

“Could I set it somewhere?”

“I’ll take it.” He reached for the dripping glass and downed it all at once.

Jane stepped carefully over the coil of hose to stand in the shade of the lilac bush. “Working hard?” she asked, realizing as soon as the words were out how lame they sounded.

“You bet,” Jess said and handed her back the empty glass.

Might as well cut to the chase. “Did you find out anything about what we found on Tuesday?”

He paused for the briefest second, as if trying to remember Tuesday. “I know where that box of books came from, if that’s what you mean.”

“You do? All right!”

Jess shoved the tip of the shovel into the paper sack, carefully drawing out some powdery, white material and tossing it into the wheelbarrow. “Just like you figured,” he said, “Sky Lake Variety Store, right there on the box. Didn’t see it till I was putting it back inside last night.”

Jane frowned. “They were your dad’s books?”

“No. They were in boxes in the storeroom when we took over. My dad gave them to the library.”

“And the letter?” she pressed. “What did you do with it?”

“I’ve got it.”

“You’re still carrying it around? I thought you were going to give it to the librarian.”

“I couldn’t,” Jess said. “She started her holidays this week. Her replacement wouldn’t know anything about it.”

“So? Did you show it to anyone else?”

“Like who?”

“I don’t know.” Didn’t he have any imagination? “Your parents, maybe. Someone who might have known the Frasers.”

Jess stirred the contents of the wheelbarrow. “I didn’t show it to anyone.”

“Oh,” said Jane. “Maybe I should just let Nell see it, then.”

“Go ahead. It’s all yours.” He set the shovel down and drew the letter out of the pocket of his jeans with two fingers.

Nell was in the kitchen washing lettuce, laying each leaf out on a clean tea towel she’d spread on the counter. At Jane’s invitation, she sat down to read the letter which Jane unfolded for her on the kitchen table.

When she was through, Nell removed her glasses, shaking her head. “I agree. Whoever Eugenie is, she sounds frightened.”

“Sounded, you mean,” Jane reminded her gloomily. “This letter is 68 years old.”

“That’s true. So whatever she was afraid was going to happen, either did, or didn’t.”

“We don’t even know if the storekeeper was able to help her or not.”

“Or if she ever got the letter,” Nell added.

“Well, Jess just told me that the book came from the storeroom of his father’s store,” Jane pointed out. “So we know the letter got that far.”

“There’s really nothing you can do now, dear,” Nell said kindly.

“Maybe not. But I’m still curious.”

At lunchtime, at Nell’s request, Jane carried a plate of chicken sandwiches covered with plastic wrap around to the side to Jess, only to discover he’d gone down to the dock. She found him dangling his legs in the water, his jeans rolled up to his knees.

“She didn’t have to feed me,” Jess growled when he saw the sandwiches, but accepted the plate Jane handed him anyway.

His dark hair curled up at the back of his neck, and he had missed a streak of white paint above the elbow of his right arm. Seeing the paint made Jane feel she had the advantage, that she knew something about him he didn’t want her to know: he wasn’t nearly as tough as he thought he was. She walked on out and pretended to check the rope that held Nell’s boat, wishing she could do it without making the dock bounce so much. She shouldn’t have eaten that second piece of chocolate cake at supper last night.

“You swim off this dock?”

Jane turned back towards him. “Of course,” she said.

“Drops off kind of fast, doesn’t it?”

“This is the deepest side of the lake.”

“And you must be one heck of a swimmer,” said Jess.

“I am,” said Jane, dragging her foot in the water and making a deliberate pattern with it on the dry planks of the dock. “And I learned to swim right here.”

Swinging his legs out of the water, Jess rested the weight of his upper body behind him on his hands and squinted up at her. “Must be nice to be a rich kid and get to lie around the cottage all summer,” he said.

It occurred to Jane that he was trying to start an argument. “A rich kid? Is that what you think I am?”

“Well, aren’t you?”

“No, I’m not. And you know something? I think you have an attitude problem.”

“So what’s it to you?” he challenged.

“Nothing. But it must get in the way of making friends.”

“So who said I needed friends?”

Jane glared at him. She had half a mind to give him a shove, send him sideways off the dock into the lake. “From the very first time you spoke to me, it was like you were looking for someone to fight with,” she said. “What did I ever do to you? For your information, I started spending summers here the year my parents split up. My grandmother looked after me then, and now my mother counts on me to sort of keep an eye on her. Until you came along, I helped her with some of the heavy work too.”

They seemed to have locked eyes in a furious stare, and to Jane’s surprise, it was Jess who looked away first. “Don’t sweat it,” he muttered, and bent to work the legs of his jeans back down over his shins.

Jane turned to leave.

“Here, you forgot something.” But when Jane reached for the empty plate he held towards her, he made a little gesture to jerk it back again. Jane gripped it firmly, with a sigh of exasperation.

“You really get steamed, don’t you?” Jess said, as she turned from him. “Okay, so I have an attitude problem. Maybe I’m working on it.”

“You need to.” Without waiting for him to get to his feet, Jane walked quickly back up to the cottage.

She spent the rest of the afternoon indoors, tidying the stacks of photo albums on the shelves in the living room, re-arranging the collection of battered duck decoys that circled the room, watching the top of Jess’s head through the side window and wondering what it was that made him so angry.

Jane dropped by the kitchen later, where her grandmother was figuring out what she owed Jess for his afternoon’s work. “So what d’you think his problem is, anyway?”

“His problem?”

“He’s got a chip on his shoulder like you wouldn’t believe.”

Nell lowered her eyes to the scrap of paper on which she was writing. “Well, let me see. His mother died not too long ago. And he moved back here, half a continent away from where he grew up. Maybe that’s it.” Jane wasn’t so sure.

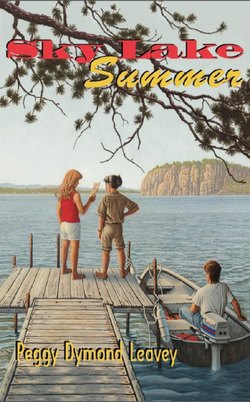

She was sitting on the dock, her towel wrapped around her after a swim, when Jess came back down to his boat about four o’clock. She had been watching two climbers scaling the massive wall of rock which dropped steeply into the lake, west of My Blue Heaven. The rock was a landmark on Sky Lake, the only feature to distinguish this lake from a thousand others nestled in the granite landscape of the Canadian Shield.

“You ever been up to the top?” Jess asked, shading his eyes to look in the same direction.

That he even spoke to her surprised Jane, let alone that he had initiated the conversation. “No, have you?” she asked.

“Sure. All the kids around here have.” So he just wanted to brag. He bent to untie the rope which held the boat to the iron pipe.

“You must have some pretty good mountain climbers around here then,” Jane said, matching Jess’s earlier tone. For an instant, he looked as though he might even smile.

“Oh, they don’t go up the hard way,” Jess admitted. “Only the real climbers go up the face of the rock. There’s an easier way to the top, a trail hidden in a little cove on the other side. It’s pretty steep, but at least it’s not sheer rock.” Dropping the rope into the boat, he held the vessel against the dock with his foot.

“So what’s up there?” Jane asked.

“Not much. Foundation of an old house. But the view from up there is really cool. So long as you’re not afraid of heights.”

“I’m not,” said Jane, amazed at the length of the conversation.

“You ought to get someone to show you where the trail is then,” said Jess, stepping down into the boat.

Jane got to her feet, tucking her beach towel into itself across her chest. “Nice boat,” she remarked. After what Nell had told her, she felt she should say something kind.

“Yeah, well, it’s not mine. My dad lets me use it, but I can’t mess around.” Jess lowered the motor into the water. His eyes met hers briefly. “See you,” he said, looking away.

Jane watched while Jess maneuvered the boat away from the dock, waiting to see if he’d turn and wave. He didn’t, but it didn’t seem to matter anymore. She found herself smiling, warmed by a feeling that it might be an okay summer after all.

On Sunday night when the rates were low, Mary called to talk to Jane. “Wonderful news, Janey,” she announced. “I asked Carol if Corrie would like to spend a few days up there with you, and she jumped at the chance. I guess, since this is the first summer she hasn’t spent at camp, she must be feeling a little lost. I can’t imagine why you didn’t tell me Corrie would be home all summer.”

When there was no response from Jane’s end, Mary went on. “I understand how much you wanted to stay here this year, Jane, but since that wasn’t possible, with my Open Houses and everything, maybe having Corrie there will be the next best thing. You’re awfully quiet, Jane. Aren’t you happy at the idea?”

“Sure, that’s okay, Mom. I just thought you might have asked me first.”

Jane remained on the bench under the telephone after the conversation was through. She was still sitting there, picking at the threads on her cutoff jeans, when Nell returned to the room.

“Problem?” she asked brightly.

“Just Mom,” Jane sighed, looking up. “She makes all the decisions for me. Did you know about Corrie coming?”

“She asked me first,” said Nell. “Isn’t it a good idea?”

“It’s not that, really. There’s lots of stuff here I can show her, I guess.” She chose her words with care. “Corrie really isn’t used to cottage life, Nell.”

“I thought you said she went to camp every summer.”

“Not real camp, Nell. Riding camp. Where everyone stays in a lodge, with a dining room and a Jacuzzi and everything. Or computer camp. Where they all stay in the university residence.”

“I see.” Nell drew a carton of milk from the fridge and poured herself a glass, part of her bedtime routine.

“What really bothers me,” Jane continued, “is that Mom never lets me make my own choices. She decides everything for me.”

“She needs to let you grow up a little, you mean,” said Nell. “Milk, dear?”

“Exactly,” said Jane, taking the glass. “Do you know she has even decided I don’t need to go and see my dad?”

“I think she’s trying to spare you, dear. You didn’t have a very good time the last time you visited him.”

“I know. But maybe things are different now.”

“Perhaps,” said Nell quietly.

There seemed to be nothing more to say on that subject, and Jane clumped upstairs to lie on her bed a while, study the familiar brown stains on the ceiling and think about Corrie coming. Without even knowing it, Corrie could spoil everything.

It wasn’t only that her friend wasn’t used to lumpy mattresses or musty pillows or outdoor toilets. Certainly, she would never understand why Nell put up with the garter snake which chose to sun itself on the flat stone at the back door; or all the spiders, whose webs caught you by surprise and which you sometimes wore in your hair all day. Corrie would be totally grossed out. No, it wasn’t only that. Now there was Jess.

Jane didn’t have much to say on the trip around the lake on Tuesday to meet Corrie’s bus. Nell took a hand off the wheel long enough to give Jane’s knee a pat. “It’ll be fine, dear,” she promised. “You’ll see.”

Jane returned a weak smile. Back in the city, Corrie Ottley was Jane’s closest friend. But that was at home; Sky Lake was different. Sky Lake belonged to her.

When Corrie stepped down off the bus, she looked like an ad for an outdoor store—new hiking boots, khaki shorts and matching blouse with barely a wrinkle, even after a long, hot ride. A gold clip held her hair off her face. Corrie’s fine brown hair was perfectly straight and shone like silk. In contrast, Jane’s blonde mane only got frizzier with the heat and humidity, and her clothes were rumpled and comfortable. After a week, most of them were still in her knapsack.

“I just didn’t know what I was going to do till you got back, Jane,” Corrie bubbled, letting Jane take one of her two matching suitcases. “I’m so glad you and Nell invited me.”

“We’re glad too, dear,” said Nell warmly. “Now, I must warn you that My Blue Heaven doesn’t have all the creature comforts. But as Jane and I always say, who needs them when we have nature right at our back door. Right, Janey?”

Jane slid the luggage onto the seat and ducked back out of the car. “Right, Nell,” she said, thinking of the snake.

Before they headed back around the lake, there were supplies to pick up from the store. While Nell filled her basket and chatted with Jackson Howard, Corrie and Jane wandered around the big, airy room attached to the front of the building and Jane got caught up on news from the home front. She had already decided she was not going to ask Corrie how the party two nights before she left had turned out, the one Corrie had been invited to and she hadn’t.

They were eating ice cream and studying the trophy fish mounted on the walls when Jesse came into the room. Seeing the girls, he stopped and took the broom he was carrying off his shoulder. “Oh, sorry,” he said. “Didn’t know there was anyone here.”

“It’s okay, isn’t it?” Jane asked. “We were just looking around, waiting for my grandmother.”

“No problem. My dad asked me to sweep the floor, is all. We had a bingo in here last night.” He was staring at Corrie.

“Oh, Jess,” said Jane quickly. “This is my friend, Corrie Ottley, from home. Corrie, this is Jess Howard. He lives here.”

Corrie tucked a long strand of hair back behind her ear and turned on her brightest smile. “Hi, Jess,” she said. She had mocha ice cream on her upper lip.

Jess leaned on the broom and continued to stare. This was exactly what Jane had been afraid of.

“You’re so lucky to live in a place like this,” chirped Corrie, indicating the view of Sky Lake and the rock on the opposite shore.

“He’s one of the lucky ones who has a job, too,” Jane pointed out. “Jess works at the municipal centre.”

Jess gave a short laugh. “You wouldn’t want that kind of job,” he said.

“What’s wrong with it?” Jane asked. “Isn’t the pay any good?”

“The pay is zip. Zilch? Nada? I’m doing community service.”