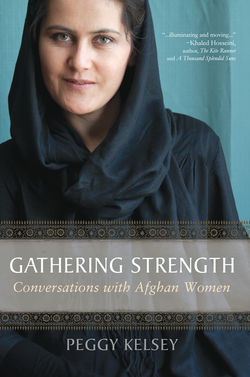

Читать книгу Gathering Strength: - Peggy Kelsey - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPeggy's Story

The Afghan Women’s Project came about by accident. Fourteen Afghan women visited Austin, Texas, on a US State Department-funded tour to get a first-hand look at American civil institutions. I was invited to a reception for them.

Alan Pogue’s1 photographic gallery, housed in a century-old Victorian converted girls’ school, hosted the gathering. Alan had visited Afghan refugee camps and his dignified, elegant, black-and-white portraits evoked gut-wrenching awareness of the refugees’ trauma and misery.

But the actual Afghan women at the event made an even stronger impression on me. They were so different from the media’s portrayal of Afghans as helpless victims. Some appeared gentle and delicate; others, feisty and strong. Some seemed energetic and extroverted; others, tired and shy. At one point Alan stood on his grand staircase and talked about some of the images. I turned and saw one of the Afghan women quietly crying. Others had tears rolling down their cheeks as they recalled events and re-experienced their grief.

The uniformly somber images, the diversity of the women, and their tears struck me like lightning. I suddenly wanted to go to Afghanistan and bring back a broader, more complete picture of Afghan women. Rather than simply raising awareness of tragedies, my goal would be to capture women’s struggles and successes through their own eyes. Alan’s portraits portrayed a truth, an important one, but only part of a reality that also encompasses many other sides of life. As a professional photographer who had lived in the Middle East, and has connections in Afghanistan, I saw I could provide a more complete picture of their lives.

As a child growing up in the south and mid-west I never intended to travel outside the United States. I saw my country as a huge, beautiful, diverse "world" that could take a lifetime to explore. As for the rest of the world, I didn’t know much about it except that it was scary out there.

Only as an adult have I learned to appreciate that my "normal" middle class upbringing was quite uncommon. My father, a Korean War veteran, spent his career climbing the ladder of a wood preserving company. Each promotion took us to a new part of the US and taught me to adapt to new surroundings. My mother seemed content as a housewife, raising their three daughters, until the day I came home from my sixth grade science class and shared a "fact" I’d just learned. She told me it was untrue, and began to think that she, with her science-oriented home economics degree, could do a better job than my teacher. And she did; she became a middle school science teacher and later a high school guidance counselor.

I grew up a tomboy, inhaling TV adventures such as "Rin Tin Tin," "Lassie," and "My Friend Flicka," featuring kids going outside their normal boundaries, solving mysteries, and outwitting bad guys to save the day. These kids (and their amazing animals!) did things their own way and became heroes.

Yet my actual life was prosaic. I was an obedient teenager. I started college in 1969 at Ohio’s Miami University and, not knowing what else I wanted to do, studied to be a teacher like my mother.

When a social work professor lectured in one of my classes, I realized for the first time that what excited me about teaching was the one-on-one relationship with young people, and that I’d be more likely to find that in social work. At the end of my sophomore year I transferred to the social work program at Kent State and began summer school. Not incidentally, Kent State was only 35 miles from Cleveland and my boyfriend, Thom.

In mid-summer, two students came into my class to talk about that fall’s exchange program to Iran. Two days later, Thom broke up with me. Heartbroken, I looked at him and spat, "Well, then, I’ll just go study in Iran!"

I’d only wanted to make him jealous and regret his decision. But Thom was a serious yoga student. "Do you know how close that is to India? You have to go." Suddenly, I was considering it….

That weekend I drove home and sat at the kitchen table with my parents, who were footing my college bills. "I’ve got something to tell you and something to ask you." They sucked in their breaths, bracing for the worst. "Thom and I have broken up." Huge exhalations; they were obviously delighted and relieved.

"And?"

"I want to go study in Iran." Then I launched into my spiel. After conferring, they agreed. Looking back, I can see that they were calculating that 35 miles separated Kent State from Cleveland, where Thom lived, while 6000 miles separated Cleveland from Iran. Also, the exchange was a university program and therefore should be relatively safe.

As I was leaving the next morning to return to school, my mother gave me a look of exasperation and asked, "Why can’t you go someplace normal like Europe?"

Iran in 1971 was not ruled by religious mullahs as it is today. Swiss-educated Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi2 sat on the "Peacock Throne," continuing his father’s policy of modernization and secularization. Iran sided with the US in the Cold War and, because it was producing and selling huge amounts of oil, was the second-largest buyer of American weapons. Socially conservative Muslims, the majority, were generally invisible to Americans. A semi-Westernized middle class was emerging in the cities. Blue jeans were all the rage.

Pahlavi University, the site of our program, was in Shiraz, the provincial "City of Roses." Elaborate rose gardens enhanced the beautiful architecture of centuries-old shrines. Roses lined modern boulevards. I loved Vakil, the cool, musty, multi-vaulted bazaar. It was built in the mid-1700s, but to my small-town eyes it seemed ancient. Small shops lined the bustling streets. Sheep quarters hung in butcher shops next to photo studios covered with movie-star-style portraits next to vegetable sellers whose produce spilled out onto the sidewalks.

We lived in ‘60s-style dorms, concrete boxes not much different from those at Kent State. The Iranian girls – in the Middle East and in Afghanistan, a girl is not called a woman until she marries – in my dorm were friendly but cliquish and I was an object of their curiosity. We’d sometimes sip tea while they asked me questions and practiced their English. I didn’t become close to any of them. In part, I found it hard to relate to girls so sheltered they had never even spoken with the boys with whom they were "in love." They reminded me of American pre-teens "in love" with pop singers. I’m sure I was just as alien to them.

A professor and I visited a nearby village during one school break. Strolling down a street lined with mud-brick walls, we came upon a store so small that the shopkeeper could reach any item without taking a step. The open upper portion of a Dutch door let customers view his goods. The elderly proprietor asked what we wanted from the half-dozen dusty cans on his shelves.

"How do you survive with so few items to sell?" my professor asked.

The man looked to the ceiling for a moment and replied, "I survive by the grace of Allah."

That hit me hard. Growing up, we commonly prayed for good test grades or to thank God for our not-fully-appreciated abundance. This was the first time I’d encountered anyone who depended on God for his very subsistence. This man appeared so simple and pure in his deeply held beliefs; how, I thought, could he be consigned to Hell, as the religion in which I was raised professed? This experience led me to believe that all religions lead to God and that we are not judged by what we believe, but how we lovingly live whatever beliefs we have.

The school year neared its end and the question of what to do for the summer arose. Should I go back to Ohio? I was already in the Middle East; when, if ever, would I be able to return? I’d earned enough teaching English during the school year to fund an on-the-cheap excursion. I’d traveled with friends in different parts of Iran and knew enough Farsi to get around. India beckoned. I preferred to travel alone, so I wrapped myself in a chador and headed out.

The decrepit, rickety bus chugged through the dusty mud-brick villages and rocky deserts of southern Iran. Despite my blue eyes and blue jeans, I was treated respectfully throughout the journey across Iran and Pakistan; I’m sure in large part because of the chador. No one knew what to make of me; with my Islamic covering, I didn’t fit any stereotypes.

I rode trains from the Pakistani border at Zahedan and I vividly recall Quetta, a city in the Pashtun heartland approximately 75 miles (121 k) south of the Afghan border. Rough wooden houses perched on cement blocks lined the tracks. Men wearing large turbans and baggy shalwar kameez, with rifles slung over their shoulders, stood around chatting. The place had the feel of the American "Wild West."

Northern India was a blur of colorful saris, fantastical architecture, and bearded, turbaned men who smelled of ghee. I was enthralled. I rode trains around the edges of India for a month-and-a-half until I reached Bombay (now Mumbai), where I was to meet my new boyfriend, Jamshid, an Indian medical student on summer break from his college in Iran.

After I’d been at my boyfriend’s house for two weeks, his brother arrived from a trip with his buddies to Afghanistan. The brother was the only one to return; the rest had been brutally murdered right in front of him. I didn’t feel it appropriate to ask what exactly had led to that fate. I had already bought my train ticket and was scheduled to depart two days later for that suddenly-scary country. Everyone tried to talk me out of going, but I refused to change my plan. I hadn’t yet seen Afghanistan, and I’d heard from other travelers that it was a whole different world.

But their pleadings had an effect. I stayed in Kabul less than a week and didn’t venture far from the beaten path. Kabuli women’s dress surprised me, especially having just come from India, where female legs were always covered. In Kabul, women walked down the street in fashionable, knee-length, Western-style dresses. Bare-headed women strolled tree-lined sidewalks in high heels and fancy hairstyles. Others cloaked themselves in huge scarves, concealing the knee-length dresses they wore over baggy pants, but leaving their faces bare.

Here and there, goldenrod yellow, olive green, or medium brown phantoms floated among the women. I’d never seen nor heard of burqas before and found it hard to imagine that a person walked beneath each flowing tent. These were traditional burqas, made of heavy cotton, not the nylon used today. They went to the ground all the way around, unlike their modern counterparts that have a shorter panel in front. When they went out, traditional women wore high-waisted homespun pants called duloq over the pants worn at home. I learned later that during this period, some Kabuli women held parliamentary and ministerial positions, worked as scientists, pharmacists, and teachers and ran their own businesses.3

When I left Kabul, I took the direct bus to Herat traveling through the desert via Kandahar rather than the three-day mountain route through the north. I generally felt safe the entire time.

Herat lies on an ancient trade route near Afghanistan’s border with Iran. Centuries-old elegant mosques, shrines, and a citadel dating back to Alexander the Great are well-visited even now by Heratis as well as a sprinkling of Afghan and foreign tourists. Queen Goharshad,4 an artist in her own right, established the Musalla Complex, a 15th century mosque and university whose ruined columns tower over Herat today. A lover of knowledge, she commissioned the educational center’s construction.

Legend has it that because the university she created was only for men and she also wanted women to study, she decreed that 200 women of her court should each marry a student, so that they, too, would have access to the extensive libraries.

A few years after that first foray to Afghanistan, degrees in hand, I left Ohio to seek my destiny in Washington, DC. I found it in the form of Bill Kelsey, a missionary kid who’d grown up in Jordan. Within nine months of meeting, we became engaged and set off on our around-the-world-on-the-cheap pre-wedding honeymoon.

In Japan, we marveled that a five-foot stack of beer cases in the alley behind our hostel was still intact upon our return later that night. In lively night markets in Taiwan we saw aphrodisiac salesmen cut the gall bladders out of living snakes, pour the bile into shot-glasses of sorghum whisky, and offer the concoction to passers-by. Electricity was just being installed in the Philippine village where we stayed, and I considered the life changes and unintended consequences it would bring. Bali was the "exotic east" on steroids. I pondered the wealth of a society that charred dozens of ducks to accompany a funeral procession. The snake temple in Malaysia hypnotized me, as well as the many snakes lounging around, and I delighted in being able to safely photograph them at close range.

Thailand presented our biggest challenge when, walking among northern hill tribes’ villages, Bill came down with typhoid fever. All the way uphill, I had seen the villages as cute and enchanting, almost a primeval Garden of Eden. Our first host said he was planning to move out of the mountains down to the road. As someone healthy and well-educated, I privately mourned the loss of his "pure and idyllic" life.

When Bill fell sick two days later, we hurriedly retraced our steps dragging ourselves back to civilization and a hospital. Now those same villages looked squalid, dirty, and poor, and I began to understand our former host’s fervent desire to be close to a road with access to medical care, schools, and other vital services.

Bill soon recovered and we eventually made it to Jordan and were married by my father-in-law. We spent our official honeymoon with my parents traveling in Jerusalem and the Galilee.

We worked in Bahrain and Yemen before returning to the US. Yemen in the late 1970s had the highest number of researchers and foreign aid workers per square foot of any nation in the world, due to its strategic location across from the Horn of Africa. One could encounter North and South Koreans, mainland and Taiwanese Chinese, and Soviets and Americans engaged in aid and development, espionage, or anthropological research.

I had studied Arabic while in Jordan and found work with Save the Children in Yemen. I felt close to local friends there but during one conversation was put in my place. I had said that the Soviet people I’d encountered were stone-faced and unfriendly, always keeping to themselves, "so different from us." My Yemeni friend corrected me, saying that Soviets and Americans were like peas in the same pod while Yemenis, being very traditional and Muslim, were from an entirely different garden.

Bill and I realized that to have meaningful careers overseas, we needed concrete skills besides language facility. We returned to the US.

My childhood dream had been to live on a "ranchette" near an interesting city. In 1980 Bill and I bought ten acres near Austin, Texas. We began building a small house, doing the work ourselves, and started a magazine distribution business. We weren’t ready to give up the simple life of our Yemen experience. As soon as the walls were up and the roof was on, we moved into the shell and tended our goats, pigeons, chickens, and a few years later, our daughters. By the 1990s the house was nearly finished. We’d saved enough money for Bill to pursue his dream of flying airplanes and for me to follow my long-buried interest, photography.

Ever since our trip around the world, we’d talked of giving our kids the experience of living in another culture. In 1997, Bill got a job as a bush pilot for Airserv, in Quelimane, Mozambique, a city with a quarter-million people but that felt like a small town. I closed my portrait-and-wedding photography business, packed up our 11- and 13-year-old daughters, and followed.

In Quelimane, I loved going around with my friend Keika, a Japanese photographer whose husband worked for the United Nations (UN). We had a routine for our bicycle jaunts out beyond the paved roads. When we’d spot something interesting, one of us would make a big show of slowly taking out her camera, leisurely focusing and refocusing, setting up everything just exactly right, while the children who inevitably appeared mugged in front of the camera. Meanwhile, the other one was quickly grabbing the shots she wanted.

I had homeschooled the girls for a year-and-a-half when they begged to go to a boarding school in South Africa like the children of other aid workers. Sending my daughters off to school gave me freedom to take my own excursions.

One trip took me down the Zambezi River to visit Mary Livingstone’s5 grave. I hired a boat in Caia and the captain, his assistant, and I motored three hours downstream to Chupanga, where the colonial cemetery lay. I eagerly jumped onto land to begin exploring but the captain and a man on the dock shouted at me. "Stop!"

"Landmines," they explained. I was suddenly reminded that Mozambique’s eleven-year war of independence from Portugal and the ensuing fifteen-year civil war had ended only seven years earlier. So I carefully followed the guide’s steps to Mary’s picturesquely overgrown grave. Just as I was pulling out my camera, another man came running down the hill to say that I first had to go with him to get official permission. We marched uphill, where the governor and I had tea and a nice chat. I returned to the gravesite with the required permission just in time to see workers clearing up after extensive pruning. To my chagrin, all of the charm had been clipped away.

In 2000, we moved our family back to Texas, this time inside Austin. I resumed my photography business while keeping my eyes open for something more meaningful.

That "something" happened the evening of Alan Pogue’s photography exhibit. Creating the Afghan Women’s Project was like having a baby. I had the conception. It took nine months to develop the vision, raise funds, make connections to meet women in Afghanistan, and attend to the many details. The project would have collapsed many times without Bill’s encouragement and support. My life coach also held my feet to the fire. Joia’s6 most important question came at a time when I was losing sight of my vision. "OK," she asked, "What if you don’t go?"

People think I must be brave to visit Afghanistan, a land of violence and war. Certain areas were very dangerous, and I avoided them. Others were quite safe. Years of world travel in developing countries have given me a good sense of how to dress and carry myself in traditional societies and what to do if things go wrong.

I was terrified, however, when I stood before a sympathetic group of American Sufis on a ranch outside Austin to ask for money for my project! At the time, I wasn’t sure I could pull it off. When I began my speech, my quivering voice and shaking legs pained the audience so much that someone spoke up to tell me that this was a very accepting group and I could relax! Getting through that speech and not running away shamefacedly afterwards required much more courage than I ever needed in Afghanistan.

To prepare for my trip, I contacted friends who might have connections or be interested in supporting my endeavor, as well as aid agencies working in the area. Offers of help and rejections took me on a dizzying roller coaster ride until I finally learned not to get attached to any particular possibility and just trust that my overall efforts would bear the needed fruit. Inspired by the courageous and dedicated Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) members I’d encountered on the internet, I contacted them for interviews, too.

As in pregnancy, the gestation finally came to an end, and in August, 2003, I set off for Kabul.

Airserv, the company Bill had worked for in Mozambique, put me up in their crew house in Kabul in exchange for photographs of their flight operation. They also flew me around the country on their scheduled flights when space was available. My situation was nearly ideal. I had the companionship of Westerners and access to an office with "safe" electricity; that is, without random spikes that could fry my computer. I also had access to a printer and could share photographs of the women I met with them.

Kabul was relatively safe at that time. People I met were grateful the US had driven out the Taliban, despite innocent Afghans having been killed in the process. I felt at ease, although remaining alert while walking alone and taking taxis.

Pictures I’d seen on American TV suggested that Kabul was a moonscape-like, ruined hellhole. It wasn’t. Yes, thousands of random civil war rockets had left piles of rubble and destroyed entire neighborhoods, but the TV and newspaper cameras hadn’t shown areas where life continued as usual. Some buildings were untouched, or only pocked with bullet holes. Even in damaged areas, buildings with their upper floors destroyed housed shops below that were open for business. Squatters had bricked in parts of broken building shells for shelter. People walked around the scars of war on sidewalks lined with vendors as they made their way to bustling markets. Life carried on.

My first few interviews went sufficiently well, but I was less satisfied with my photographs. I was slowly getting my feet on the ground and developing my shooting technique. After a week, RAWA still hadn’t gotten back in touch with me to visit their projects. Making other contacts to find interview subjects was going slowly, in part due to erratic phone service. I only had two weeks left and I felt devastated.

Had I come halfway around the world, and accepted the financial support of my friends, only to do something mediocre? I cried. I prayed. I meditated. Within thirty minutes RAWA called. I got through to other groups who were happy to introduce me to interview subjects. The idea for my signature shooting technique came to me, allowing me to get natural images, slices of the moment. I learned that getting a visa extension and changing my flight would be easy.

Before I left Texas I’d feared I wouldn’t find anyone willing to talk with me and be photographed. The opposite turned out to be true; many women were eager to share their experiences and didn’t mind having their pictures taken. I began to see that especially for uneducated, impoverished women, having a Westerner come all the way to Afghanistan to listen to them and acknowledge their pain and difficulties could be empowering, affirming, and healing.

The powerful need to tell one’s story was brought home shortly before I left the country. I had just completed two interviews at a literacy and tailoring school. As I was leaving our interview room, I saw fifteen women sitting against the wall, each waiting patiently, hoping to be heard. Unfortunately, I was unable to stay longer.

The visa extension allowed me to visit Taloqan, a city of 64,000 people located 150 miles north of Kabul. The director of an aid agency had invited me to stay in the agency’s spacious compound on the edge of town. After breakfast the morning after I arrived, I set off alone looking for interesting pictures. But as soon as I slipped out the gate, the guard7 came running after me, saying that I must have an escort in case I got lost. Well, Taloqan is a small town and I have a good sense of direction. But I understood that when staying with Afghans, whether an organization or a private family, they assumed responsibility for me and it would be rude, impolitic, and – who knows – possibly dangerous to go wandering alone. So as I walked the guard trailed behind, and I must admit I felt secure having someone watch my back while my eyes were glued to the viewfinder.

The modern areas of this provincial capital had two-story buildings filled with shops selling gadgets from China and Pakistan. Private cars and taxis shared the road with brightly-decorated horse-drawn taxis, donkey carts, men or kids on donkeys, hand-carts, and pedestrians.

But the vegetable market with its rows of rickety wooden carts filled with fruits and vegetables and the outdoor grain market seemed right out of a Rudyard Kipling novel. I only felt discomfort there, a place of no women. Watching grain being weighed and sold, it was easy to imagine that I was observing life centuries ago. The use of plastic grain bags rather than hemp sacks was the only apparent anachronism. Although I only peered in from the road, I could see the merchants’ brows furrowing and eyes narrowing, as if telling me that I didn’t belong in this male enclave. So we moved on.

Returning to Texas six weeks later, I created a photo exhibit that included a short biography and an excerpt from each woman’s interview to hang beside her portrait. Slide show presentations to civic groups, churches, and universities soon followed, enabling me to share the women’s stories as well as my own perspective on what I had seen.

The process of carrying out the Afghan Women’s Project changed me in profound ways. I’d become more confident, developed strategies for dealing with my personal shortcomings, found information and resources to help me define my mission and purpose, and learned to craft statements to solidify my vision. I wanted to share what I’d learned, so I began giving workshops to encourage and help others with their creative endeavors.

A few years later I began to feel Afghanistan calling me to return. This time, in 2010, I entered the country on a tour with Global Exchange8 so I could gain access to women I might not have met otherwise. These dedicated leaders showed me a side of Afghanistan that seldom made mainstream news.

When the Global Exchange tour ended, I stayed with the School of Leadership, Afghanistan (SOLA). Here I met a wide range of delightful young people, all of them seriously dedicated to helping rebuild their country. They lifted me out of the discouraged mindset I’d developed from focusing on political and military developments.

Afghan youth, like people everywhere, run the gamut from selfish to idealistic. But the SOLA students and others inspired me with the possibility that through their hard work and dedication, their nation may one day enjoy competent leadership and relative justice. It won’t happen before the next election; it will likely take until these youths are middle-aged and current leaders have retired or died. But if these young people stay true to their dreams, then I believe their hopes might just be realized.

In the seven years since my last visit, Kabul had changed. In 2003, I felt safe walking for miles along city streets. In 2010, I was warned not to walk anywhere. In 2003, I’d hailed taxis off the street. In 2010, I was told to use only certain vetted taxi companies that would pick me up at my door in unmarked cars. Traffic in 2010 was heavier and slower, the air even more polluted, and the city an armed camp.

Guards in towers above fortress-like walls looked down on traffic and pedestrians. Sandbags lined the street-side walls of important buildings. Blast-proof fifteen-foot molded concrete barriers along the streets protected ministries. Short barriers protruded into roads, forcing drivers to weave slowly around them. Afghan National Police with loaded AK-47s were everywhere. Female guards patted me down and searched my bags anytime I entered a public building. A few times every week I’d see a convoy of Allied military vehicles, but I never saw those soldiers walking around. I was surprised by how quickly I got used to such an armed environment.

One highlight of my trip was a visit to Bamyan. After Kabul, I was in heaven there in the central highlands. I walked miles every day through crisp clean air to interview women or get internet access at the university. There were few taxis. I hired a guide to tour the caves in the Buddha-cliff9 and learned that they were all hand-dug. Bright remnants of beautiful frescos have survived over two thousand years in some of these caves. I saw one soldier, a UN guard, the entire nine days I was there.

Bamyan is a small city in the Afghan central highlands, also called the Hazarajat; or the place of Hazaras. Bamyam is also the name of the province. The Hazaras are mostly Shia Muslims, while the rest of Afghanistan’s population is mostly Sunni. Bamyan City is home to more than 61,000 people and lies about 150 miles (241 km) north of Kabul. In 2010, a journey on the more secure of the two routes from the capital took about eight hours. Now, on a newly-paved road, travel time has been cut in half. Tourism has and will continue to aid in bringing resources to Bamyan and tourists to nearby Band-e Amir National Park.

The city’s mile-long bazaar meanders alongside the Bamyan River. Small shops, kabob stands, and a few two-story hotels flank the street. Between the rear of the shops and the river containment wall, rows of vendors sell vegetables amid makeshift stalls full of cheap Chinese goods.

Beyond the bazaar, the road crosses the Bamyan River at an angle and intersects a branch of the famed Silk Road.10 A line of cliffs parallels the road as it heads east toward Kabul and west, in front of Bamyan Hospital, to the Buddha grottoes, and then out of town towards magnificent Band-e Amir.

A mixture of ruins, mud brick houses, and a few cement buildings lies in the triangle formed by the bazaar and river, the Buddha wall, and a connecting road. A midwife training center, where I interviewed Kobra (found in the Women's Health Workers chapter), is located there. A wall of inhabited caves stretches well beyond the World Heritage "Buddha section" in both directions. Suburbs containing government offices and modern housing continue to spring up around the edges of the city. Now that Bamyan has electricity every evening, television satellite receivers occasionally appear on top of mud-brick houses. The internet is non-existent, except in offices or the university.

From Bamyan I rode five hours over gravel roads to Yakolang to visit the Leprosy Control (LEPCO) clinic where people with tuberculosis and leprosy stay until cured. I sat in the sun with some of the women and watched one embroider a large curtain while we tried to communicate with my broken Dari. From there I went to Band-e Amir, where I spent four days hiking in the clean air and staying with a village family. At 8000 feet (2438 m) above sea level, I found fossilized brain coral lying on the cliffs above an amazingly deep-blue lake. Each evening I shared the day’s photos, letting my hosts see their everyday environment through my eyes.

My purpose for this book is to break open stereotypes. I want to expose readers to stories that challenge assumptions. I hope to help you see Afghanistan, her people, and their issues in a more nuanced light.

Biased, one-dimensional information in the mass media, from across the political and philosophical spectrum, guides people to view the world according to particular agendas. Important issues are conflated, leading people to form simplistic ideas about possible solutions. I long to see positive efforts in Afghanistan that will still be effective after 50 or even 100 years. This will only happen if participants take into account deeper issues behind the problems, and if reforms are directed by Afghans in a distinctly Afghan way.

Why do I focus so much effort on women? Men have most of the power in Afghanistan. It’s critical for young boys to grow up seeing women as human beings, as contributors to the family and society, as partners. Women, who will bring up the next generation, must first have that vision of themselves and their gender before they can pass it on to their sons and daughters. Through the portraits, conversations, and stories here, I hope to encourage that vision.