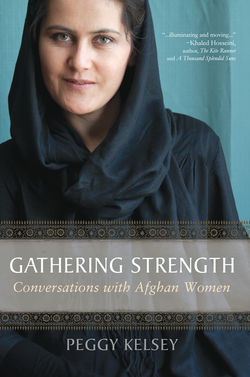

Читать книгу Gathering Strength: - Peggy Kelsey - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPoems by Forugh Farrokhzad

Afghans and Iranians share similar languages (Farsi and Dari) and the love of poetry. Both Setara and Elaha mentioned Forugh Farrokhzad, a modern Iranian poet, as their favorite.

The Captive is about the poet having to give up her son should she divorce.

The Captive

I want you, yet I know that never

can I embrace you to my heart’s content.

you are that clear and bright sky.

I, in this corner of the cage, am a captive bird.

from behind the cold and dark bars

directing toward you my rueful look of astonishment,

I am thinking that a hand might come

and I might suddenly spread my wings in your direction.

I am thinking that in a moment of neglect

I might fly from this silent prison,

laugh in the eyes of the man who is my jailer

and beside you begin life anew.

I am thinking these things, yet I know

that I can not, dare not leave this prison.

even if the jailer would wish it,

no breath or breeze remains for my flight.

from behind the bars, every bright morning

the look of a child smile in my face;

when I begin a song of joy,

his lips come toward me with a kiss.

O sky, if I want one day

to fly from this silent prison,

what shall I say to the weeping child’s eyes:

forget about me, for I am captive bird?

I am that candle which illumines a ruins

with the burning of her heart.

If I want to choose silent darkness,

I will bring a nest to ruin.

The Sin

I sinned, a sin all filled with pleasure

wrapped in an embrace, warm and fiery.

I sinned in a pair of arms

that were vibrant, virile, violent.

In that dim and quiet place of seclusion

I looked into his eyes brimming with myster

my heart throbbed in my chest all too excited

by the desire glowing in his eyes.

In that dim and quiet place of seclusion

as I sat next to him all scattered inside

his lips poured lust on my lips

and I left behind the sorrows of my heart.

Peggy: What do you think is the greatest enabler of your success as a singer?

Elaha: The most important ingredient of my success is a commitment to good morality. Many people think that if a woman sings on TV, she is a prostitute. It’s important for me to be an example that this is not the case.

Peggy: Sahraa, what do you want to accomplish with your films?

Sahraa: I want to find my identity as a woman, not as a refugee girl. Growing up in Iran, the shadow of being a refugee girl from Afghanistan was a limitation that made me want to improve myself. It gave me a challenge. That’s one reason I moved to Slovakia. Only by living in another culture could I find the identity I had lost in Iran. It’s very important that people start to search inside themselves. Everyone’s way of searching is different. For photographers it’s to take photos; for writers it’s writing; for me as a filmmaker, it’s to make films. I find that filmmaking is a kind of questioning, a way of finding my identity that they stole from me.

Identity, for me, is to show myself as I am, not how society thinks I should be nor how they want me to be, but how I really am, including all my mistakes. We are all human beings and we all have different sides. Identity means that I say what is on my mind. I don’t censor myself. It is very hard to be like this in Afghan society. In Slovakian society I could say what I wanted. Maybe they wouldn’t agree with me or like me, but at least I had the power to speak my truth. Here, we don’t have this power.

Here people judge you. Afghan society in Iran did the same and I hated it. To avoid this judgment I decided to live somewhere else. I wanted to be free to speak without worrying that if I say something, maybe I will hurt someone or maybe somebody won’t like me. Through art, and especially film, I can speak out. Film helped me overcome my shyness about my face and body and to speak about what this body likes and doesn’t like.

But when I began to really think for myself, I started to make mistakes. These mistakes brought me back. Sometimes it was very painful, but I’m happy that I did these things because they helped me find myself.

Peggy: Saghar, tell me about your painting. (Seen in her portrait.)

Saghar: This painting is one of my first ones. I wanted to show the world the Afghan people’s misery. You see that both of these doors are closed. Rich people live behind that beautiful door, poor ones behind the other. But it doesn’t make a difference to that boy in the foreground, sitting under the tree in the snow. Neither one is helping him. You see these animals, the crow and the wolf? The animals have feelings for the boy, but the people in the houses don’t. There is no humanitarianism here.

Peggy: What do you think about art and its importance in society?

Saghar: Here in Afghanistan, unfortunately, people do not pay attention to art. Because of the lack of education they never think about it. But personally, art helps me a lot.

Peggy: Will you ever be able to show or sell these pictures of people and monuments that you have here?

Saghar: No, no one appreciates this kind of art. I also paint geometric designs on colored vases that my husband sells in his pharmacy. The other paintings will stay in my house or I may give some to my relatives.

Peggy: How will you use your art after you graduate?

Saghar: I’m interested in teaching, but here, if students want to be teachers, they have to choose that when they begin their studies. It’s too late for me now. After I graduate, I will just paint here at home and raise my son.

Peggy: Mariam:, what drew you to photography?

Mariam: Some people say that they’ve always wanted to be a photographer, but not me. I was working in public information for the Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR), writing an article about cultivating saffron. It needed an illustration, so someone lent me a camera and I took some pictures. They loved them. Those pictures led me to take a course at Aina Photo Agency here in Kabul. I also had to learn English. During that program I took a picture of a laughing mullah and the instructor was so pleased that he helped me sell the photo to a magazine. That’s how I got the idea that I should try to become a photographer.

But now in Afghanistan people don’t appreciate photography. If they ask you what you’re doing and if you say you’re a photographer, they don’t understand, and they say, "Photography???" It’s a question mark in their minds.

Sahraa: This film I made, Women Behind the Wheel, wasn’t perfect but it was very open. It portrayed how I saw Afghan society at the time. When I came here from Slovakia and started to live with my in-laws inside Afghan society, I began to communicate with a different kind of people. I saw that the truth of the film was much more painful than this picture showed. A lot of women have a very bad life inside their family. From the outside you can’t see it; they have nice clothes, they have children, they are busy with things to do, but they are always being there for other people and they never think about themselves.

You can see lots of girls who are very modern, who wear stylish clothes, who laugh in the street. But if you talk with them, you can see that they still don’t have their power. They don’t have the ability to say what they want because they are still afraid. For that, I want intellectual people to stand up and speak their minds. I think they would have a lot to say.

Everybody’s story is very important. For me, as a woman in Afghan society living inside Afghan culture, there are a lot of things I should tell but I can’t. Our society is not very open and it doesn’t give me the opportunity to tell these things. Here, culture and everything should be moral. Your behavior, your way of thinking, your way of life, everything should be moral. Because of that, I think the story of the Afghan girl and the Afghan woman has a very specific color, a dark color. For me as a filmmaker, it’s important to show this color in a true way, and through these women tell the story.

Everyone thinks that women here don’t have rights; that they don’t have the right to speak. Okay, that’s true. But there is something more important. Afghan women don’t have a chance to know what they think. They always live for their family, their husband, or their children. It’s their way of life. You can never tell them that this is not the right way. They believe that it’s right; they’re proud of it. When you’re proud of something, you can never get away from it. When you’re proud as a daughter, you should be with your mother because society says so, but you can’t be a "good" daughter and a "good" wife, and also be good for yourself.

Peggy: Sahraa is very "un-Afghan." The things she points out about Afghanistan are also true here in America in certain subcultures.

What about film directing excites you?

Sahraa: Filmmaking is a way of thinking. It’s a way I can express my thoughts, opinions, and ideas about society, myself, women, and people. I can communicate my agreement and disagreement with what I portray. Most important for me is that it’s a way of thinking about the world in general. Filmmaking is about more than technique or technical issues; it’s how I view my culture, how I criticize my culture, how I see. To make films and especially to direct films is my life’s commitment.

Peggy: What advice do you have for someone who wants to be a photographer?

Mariam:: Not only for being a photographer, but if a woman wants to do something but doesn’t have much courage, or if she feels weak or not capable, I say, "You have abilities you can use to help people. Whatever skill you have, you have to look for it, you have to seek it out. Then you can go ahead."

Peggy: What do you like most about photojournalism?

Mariam: Through taking pictures, I’m getting to know about women’s personal lives, the way they’re living, and how they overcome their difficulties. We have a

lot of problems in Afghanistan, especially in the rural areas. I remember my time in Bamyan Province. When I talked with a woman in a small village I saw how difficult their lives are, especially in the winter. The roads are completely blocked and if a woman is pregnant, she might die. There is no nearby clinic so if something goes wrong, nobody can help them. And there’s no school for the children.

It makes me wonder... Security is good. There is no fighting like in the south; this area is completely safe and calm. The air is clean; the landscape, beautiful; and the need, so great. Why aren’t there more projects to help these people? Women’s development is mostly in the cities. I’m fine with that; I can work there. But just once think about those people in the very remote areas. Where are the development projects for them?

Peggy: Have you experienced people reading something you’ve written and saying that it changed their lives or changed their thinking?

Setara: Yes. When I write in Farsi, I only share it with my close friends. When I read them my poems the first time they told me, "Please continue writing, Setara."

Otherwise no one knows I’m a writer. I’m sure that if people knew they wouldn’t like it. They think that whenever a woman writes, there is a fault, especially with the reality. I’ve experienced this. Whenever a woman writes, people think she should be at odds with society and therefore lose something. As in the case of Forugh Farrokhzad, her outspoken writing caused her to lose the respect of her

family and friends. She lost one thing and gained something else. This is how people see all women writers.

But for my English writings... on the AWWP blog, readers make comments and those comments change my writing, change me, and change the way I think. They write things like, "Wonderful, excellent, amazing." When I see that my writing has readers, it encourages me to continue. My English writings are improving. I really came to trust myself only after people remarked on my writings. Now, I’m one of the most active writers. When I write in English, I feel that I can express most of my feelings, and I can share my experiences and pain with others. Now, 44 of my writings are on the web. On March 8, 2009, at an event in California, a well-known Hollywood actress read my poems. I was so proud and it encouraged me very much.

Peggy: Do you ever translate your Farsi writings into English or is it too different?

Setara: The feelings come in English and I automatically write them in English, or my feelings come in Farsi and I write them in that language. Someday when I get time, I will translate them, but I am very busy right now. I want to start a small group of women writers. We can be a good example for Afghan women and help bring positive changes. We can learn from each other so that we will stand on each other’s shoulders.

Peggy: I asked Saghar, the painter, if there was a student art association or any association of female artists in Herat but she said, "No." I suggested that while she was still in school might be a good time for her and some of her classmates to start one so they could encourage and support each other throughout their careers. I started a photography group while in photo school that continues to provide resources, camaraderie, information, and support. Connecting with other artists raises my spirits and can help me overcome artist’s block.

When I returned to Herat in 2010 the phone system had changed, and I couldn’t contact Saghar.

Mariam: My freedom to come and go did not happen easily. When my director first asked me to travel to Herat to translate for them, I told her that I could never get permission. So she came home with me to talk with my father. In the end he laughed and said, "Since you have come to my house, I cannot reject you, so I will let her go." Everything went smoothly. Shortly afterwards, she wanted me to return to Herat but this time my father said, "I let you go the first time and now

you come asking me again. No, it’s not possible." So, I cried and tried to convince him, and over the weeks kept asking him until he finally agreed.

I told him, "I was born in war and I will die in war. I can’t wait for a better situation."

He laughed and said, "I wish you were a son."

I said to him, "Look, my Father, if anybody outside our house sees me and my attitude and the way I talk with people, they don’t look at me as a girl, they think of me as a man." So this is how I became able to go outside of Kabul and even outside the country. I went alone to the Netherlands and to India for training. Now he allows me to work on projects that require me to be away for even three weeks at a time. Here in Kabul, sometimes I have to work late at the print shop. He just asks that I call to let him know I’m OK.

It’s not a crime to travel alone or come home after dark, but it has many problems. Maybe your father or brother doesn’t agree. Even your mother and your sister might feel that because you’re a woman you are weak. If you go, and something happens, everybody will talk about you, every relative will say bad things about you and your parents for letting you go.

Peggy: What is the most difficult challenge in your career and how do you deal with it?

Mariam: Aside from my father, society is also a problem for me. A career in photography is not known or respected. Normal people laugh at me and ask why am I spending my time learning these things? It sounds crazy to them. But I always explain that I get paid for it and many people want to hire me. They come to accept it just by my talking with them.

Peggy: What are some of the issues you are facing in your life?

Mariam: One of my brothers is sick and can’t work. He has a daughter and son but he’s not able to support them. I have to do something to help them and to help my mother. My other brother is only in seventh grade and the government schools are not places where he can learn well, so I put him in a private school. Every three months I have to pay $400, big money in Afghanistan. But anyway, I have to make it.

Peggy: Mariam’s story belies what we are led to believe about Afghan men’s intractability. I interviewed many determined women who wanted something badly enough to stand up to their fathers or brothers to make their case. Very often they received the permission they sought. In some instances it happened after a person from the outside, sometimes an Afghan woman in authority, or in this case Mariam:’s foreign female boss, made the effort to go to their house, drink tea, and make a plea on the woman’s behalf. It might take more than the proverbial "three cups of tea," but men can many times be convinced if a way can be shown that will ease their deeper concerns. Of course this takes time, but that doesn’t make it impossible.

Traveling alone and returning home after dark pose real risks for Afghan women. People are curious about their neighbors’ business, and if someone happens to notice that a woman is coming home alone after dark, rumors can spread that she is out misbehaving. "After all, why else would a woman be out after dark?" These sorts of rumors can lead to difficulty in finding the girl a husband, or in extreme cases, to her conviction for adultery. This is a little less of a concern for Mariam’s family because they don’t have conservative family members living with or near them. However, if anything were to go wrong, her reputation as a respectable girl could be in jeopardy.

One significant detail: Mariam:’s dad wasn’t letting her go off on pleasure trips with girlfriends. She was going to work. Her liberation and travel would earn needed money for the family, specifically for her brother’s schooling. Their children’s earnings are the main social security Afghan parents have. When women contribute to the household income, not only are they more respected, but they receive more freedom as well. People think photography is a crazy thing to pursue until Mariam tells them that she earns money doing it. Afghan photographers earning a living with photography bring legitimacy and respect to the whole profession.

Sahraa: I married a man that I never knew before. It was totally my choice. Sometimes I think I’m very stupid. I take a lot of risks in life. But in this marriage I started to notice society more and more. My husband is totally different from me. He doesn’t talk about art, he doesn’t even like art. In his eyes, everything is political. But being married to him is another kind of searching. It’s another experience. I’m sure that I’m not going to divorce him, because every day I learn something new about him that teaches me something new about myself. Through him, I started to really notice society. If I want to speak about and criticize this culture, then I need to know about it from experience, from the inside. I live with my parents-in-law. They’re totally religious, traditional people. They always pray. I don’t pray, and I come like this, in blue jeans. I don’t limit anybody in my house, I am just myself. I create a question in their minds.

Peggy: It seems that even though your parents-in-law are very traditional, they don’t try to control you much.

Sahraa: My PhD is important to them. They always say, "You are a very educated woman, so you know what you do." But I also have very good support from my husband. This is a key point. So when my husband agrees with something that they don’t like, they go along with it, but it’s very hard.

For example, last week I appeared on Tolo TV. We were all watching it together after supper. When they saw their bride on TV, it was like I had dropped a bomb. They felt ashamed and my father-in-law didn’t speak with me for two days. He’s a very good person, though. Yesterday we were at home alone and got a chance to talk. So I asked him, "Why are you so angry with me?" I am the first bride who has spoken with him so openly. He started to tell me that it was shameful that I spoke about cinema on TV. I said, "Okay then, what should I talk about? Cinema is what I studied; this is my work."

He replied, "I don’t have a problem with you being on television because I know that not every woman who appears on TV is a prostitute. You can speak on TV but don’t speak about cinema." It’s good that he improved a little. At least, he said I can be on TV. He is from this country and thousands of people think like he does. Also, thousands of women are like me, they have talent and want to be filmmakers. Unfortunately, they don’t have the opportunity to go abroad, to transform their thinking, to come back to Afghanistan and be a rebel. I don’t want to be a rebel, really. I want a very normal way to change certain things. Even if this change is very small, it’s still change.

I’m only 27 so it would be very egotistical to think I can change his mind. It would be selfish really. So I don’t try to change him, but to show him another way and help him be more open-minded. For example, my brother-in-law’s wife wears a burqa. I don’t. They don’t speak with men, but I do. I listen to opera and sing it in the house. My brother-in-law keeps saying, "Why doesn’t she wear a burqa?" and my father-in-law just answers, "That’s how she is." But now I cover myself up more [with a hooded long-sleeved cloak] when I go out because it’s good not to provoke or embarrass them. I respect them very much, but I don’t want to play the role of someone I never knew. I was a good daughter, but my father died. So now, for whom should I be a good daughter?

Peggy: I talked with Sahraa again in May, 2012 when she was in California, presenting her films at the Berkeley Iranian Film Festival.

What did your mother have to say about your marrying your husband?

Sahraa: She and my family didn’t want me to marry him because they know me and could see how different we are. But they didn’t pressure me.

Peggy: Are you still married even though you live in Slovakia?

Sahraa: Yes, and when I go back to Afghanistan I stay with my family. I accept and love them and they feel the same towards me. We get along fine. Before I married I told my husband that I am a filmmaker and that is the most important thing for me. He doesn’t mind that I travel a lot and he doesn’t want to live in Slovakia.

Peggy: Is there resentment or jealousy between you and your burqa-wearing sister-in-law?

Sahraa: No, I love her and we get along well. I have convinced her not to wear the burqa and her husband has agreed. The problem is that people in Afghanistan don’t think with their minds, they think with their eyes. What they see others do is what they think is right. Wearing a burqa was a habit for her, but when I pointed out that it’s not necessary in Islam, they changed their minds. All of my in-laws are very tolerant and we respect each other.

Peggy: What projects are you working on now?

Sahraa: I just finished a film on the life of Suraia Perlika. (See the chapter on Suraia in this book.)

Peggy: How was it when you were a little girl growing up? Did your parents encourage your art?

Elaha: My parents loved their daughters and always encouraged us to be politicians, business women, or engineers, but not singers. They didn’t hate art, but they were concerned about how society would accept me as a singer. So they were against me becoming a singer.

Peggy: So how did you fight against that, because now you are a singer?

Elaha: Even now my parents don’t like me to sing. I love my parents but that doesn’t mean that their ideas are always right. They have to accept me and I have to accept them. Traditionally in Afghanistan, singers have never had a good reputation. This makes it much harder for me. This attitude puts a lot of pressure on my family, especially my parents. Before I sang onstage, my parents had a good relationship with my entire extended family. But my conservative uncle had a big fight with my mother when I was singing on Afghan Star. Now he and his family have stopped socializing with us and they won’t come to our house. They accuse my parents of changing their culture. I have to be careful now because some people don’t like me because I’m a singer.

Peggy: Even without all this repression from society, it’s hard enough to be an artist. I’m wondering where you find the strength to stand up to this.

Elaha: First of all I have self-confidence. When I was young, my parents always encouraged me and they believed that I could achieve something great. I have always been a leader among my friends, so that gives me confidence, too. Believing in myself, my talent, and skill is the most important thing.

Our society has suffered a lot and our generation has different ideas from our parents’ generation. We have to sacrifice in order to bring the changes we want to see.

Peggy: When you encounter people trying to stop you or condemn you, what is your response?

Elaha: It depends. If somebody tries to put me down I will ignore them. This way I can make them feel that they didn’t touch me. Other times I will try to give them my reasons.

Peggy: What is the best part of your life so far?

Setara: The best part of my life is my education, my struggles for my education, and the conflicts I face. Whatever I see I find interesting and it becomes the best part of my life. Most Afghan women are far from education. If they try to continue, they have to hide it in the kitchen while they stay at home and raise their children. I’m not going to be like those women. I’m going to change my life and think differently. I’m going to experience the things that are my right. I have to show my sisters, my friends, my family, and Afghan women all over the world that we can change if we have a chance.

Peggy: During those five years under the Taliban, did you have poetry, were you interested in literature?

Setara: Yes, I studied poetry, but I was not writing at that time, only following my English classes at home with my father. Sometimes I took courses like knitting, and I can make many nice things now.

Peggy: So during the Taliban, were there things that helped you deal with depression and sadness?

Setara: There was nothing because I was not writing, just studying. I had my poetry books and my diary notebooks, and whatever poems were my favorites. I spent my time trying to memorize them. I lived the way the scholars and the classic poets lived, in a sort of monastery. Now when I write, it is my healing. If I don’t think that I’m a writer and if I can’t write, then for me there is nothing. I have to express myself.

Peggy: This impulse and even compulsion to express is the driver of the "artistic soul." Sometimes what comes out is beautiful; sometimes ugly, but it is the truth as seen or felt by that person in that moment. The truth can be different in another moment, and that also can demand expression.

When something happens to you that you don’t like, how do you react to that?

Setara: Afghan women and girls hide everything inside. They feel a mountain of pain and have no way to struggle against it. I am the same as others, but now whatever I see I write about. Positive or negative, it doesn’t matter. If I limit myself and write only about positive things, I can’t write. I’m not going to hide anything in my writing. Whenever you try to hide something, you cannot present reality.

Peggy: How did your art help you get through difficult times?

Saghar: In those [Taliban] times we could do nothing. We couldn’t go out. We couldn’t visit our friends. My only choice was to work inside my home and leave everything else to the almighty Allah. When I felt bad and when I was suffering, I painted. It helped me forget my isolated condition. Do you see this [7 foot tall] painting of an ancient pillar? I painted it from a picture I had. By painting it, I was able to bring something from outside into my house.

Peggy: In order to create my own art, I need a conducive space. I need quiet. I need the space of mind to let my spirit soar beyond my physical surroundings. I need to be in the "right" mood. When I’m down, I just don’t feel like being creative. If I do work during those times, my art reflects that and the result is mediocre, half-hearted, and forced. Harnessing anger to make art is another story. Depression, however, is much more prevalent in Afghanistan, one consequence of a cultural norm that seeks to protect loved ones from unpleasantness.

Listening to Saghar, I wondered if I could have created anything under the circumstances she endured. The truth is, at that time, during the Taliban she wasn’t being very creative either. Her simply-drawn children’s faces featuring huge sad eyes were a worthwhile exercise. They did express her feelings, but they were copies of pictures popular in the 1960s that she found in books. We didn’t discuss it, but perhaps painting those faces had also been a small rebellion. Had the Taliban discovered her paintings of living beings, or her books of images, they would have been destroyed and she would have been punished.

One day back in Austin I attended a lecture by my friend Jen O’Neal about her work in Uganda. She told us stories of women who had sustained or been forced to perpetrate horrific atrocities. Although those women she met certainly had residual emotional effects as a result, she told me that they were generally not depressed. They had access to their emotions, both positive and negative.

I thought about this in comparison to the Afghan women I’d met. I realized that there was a key difference between the two groups.

In 2003, I asked women in Welayat prison5 how they supported each other. A few told me that when a new woman came into their room, they encouraged her to tell her story and they cried together. Their mutual tears helped them bond as each woman in the group took on some of the storyteller’s pain. By connecting with their own similar stories, they could begin to heal their traumas. These women in the prison were strangers who had already fallen from respectability by being jailed. They didn’t feel the need to protect each other’s reputations or dignity as they might have with relatives or the still-respectable. When I asked women outside of prison how they most often dealt with the difficulties they faced, many said that they hid their troubles so as not to add to the burdens of their loved ones. Silence is a prescription for isolation and depression.

Whether Ugandans or Afghans, those who move forward are actively engaged in creating better lives for their children and/or the wider society. They heal more quickly and have access to the most joy. In Setara’s case, she moves forward and finds healing by sharing in her writing the experiences of Afghan women.

Who helped you get through your hard times?

Mariam: My cousin. When the mujahidin came to Kabul [1992], my uncle, who had already gone to Pakistan, advised us to join him. So my father closed up his wood heater shop and we set off. We lived in Pakistan for 11 years while my brothers, sisters, and I studied. My father sold tea and cold drinks in the bus station because he couldn’t get a job. He was the only one supporting us – seven children, my mother, his mother-in-law, and grandmother.

When we first went to Pakistan, I was very weak in studying. On the first day of school they put my younger sister in fifth grade and me into second, even though I’m older. How can it be possible for me to be in second grade and my younger sister in fifth? It’s not fair! I refused to go to school for one year because of this.

But one day my cousin told me, "Right now you have a lot of time, so what does it matter if you go into the second grade? If you study, you will soon be promoted to the fifth and then sixth. You can be in the top grade if you want. If you don’t go to school, you will spend your life doing hard work and sitting in the corner. You won’t have any talent; you won’t have anything. If you don’t get educated, one day your brothers and sisters will tell you that you are only good for washing their shoes." That hit me hard. Then she took my hand and led me to school saying, "I’m not going to let you just sit at home and do housework."

Peggy: What gives you hope for Afghanistan?

Setara: The struggle and hard work of the young generation, both women and men, give me great hope. When I see how hard they’re working at the university, how they’re trying to build their personalities in both their personal and social lives, I’m optimistic that that there will be something good in our future. I grew up in war, conflicts, rockets, and fire; everything that was in Kabul. I can remember

that time, and even now I continue to experience the bomb blasts and suicide attacks. At that time I just watched. Now I write about it.

Peggy: What do you see for your future?

Elaha: I don’t have any idea because I’ve never felt like I belonged to this country. I’ve always seen myself as an outsider. Perhaps it’s because I was raised in Iran... My life is so different from others’ here and that’s why I never feel like I’m an Afghan. I feel like I’m in Neverland and that I am not of this world. I grew up in Iran, but I’m not an Iranian either. In some ways I feel very alone and there are a lot of young people who feel the same way.

Peggy: After her interview, Elaha offered to perform for me. She called a guitarist friend to accompany her and then took me down to her tiny practice room. As she sang, I watched her lose herself in her music.

Afterwards, she led me into her bedroom. It was a small, neat, well-lit room with a single bed in the corner and a desk on the far side. The black walls had been stamped with chalky, white handprints from the lower corner at the foot of her bed up to the ceiling above her pillow. The fingers reminded me of the feathers of a bird taking wing, flying out of a black prison. In the far corner, opposite her desk, hung a noose, a hangman’s noose. She stood under it, tilted her head, stuck out her tongue and asked me to photograph her.

I was taken aback by this artistic expression of what many Afghans live with and the fact that she wanted to share it with the world: that death is always nearby, an option should things get too bad. Although their lives may look fine from the outside, the artist’s life-path can be one of danger and loneliness.

Sahraa: I must tell you, we are a lost generation. All of us, because of our society, lived our lives for our mothers, fathers, or family and then when we started to live for ourselves, it was a little late. We must respect everybody, our in-laws, our parents, our elders, but we must also start to realize what we ourselves want, because our life is very short.

The Bird Market

Peggy: Mariam and I took a photo excursion into Kabul’s bird market and surrounding neighborhood. What a gutsy woman she is! Our one option was to go on a Friday, the only day of the week when her print shop was closed. By the time we got to the bird market, the narrow alley was filled elbow-to-elbow with men. Not one other woman was in sight. Both sides of the cramped passageway were lined with cages on top of cages, each filled with pigeons, parakeets, kabks (Chukar partridge, a bird used for fighting), and more. Above the birds, empty baskets and cages precariously lined the edges of the roofs. Mariam plowed right in, with me in her wake. We’d walk a bit and then step up into a shop doorway, stepping out of the river of men streaming by to get our shots. Yes, I was a little nervous entering into this commotion, but felt safe enough following Mariam. The whole time I was never harassed nor touched inappropriately. I also couldn’t understand what anyone around me was saying.

At one point, Mariam turned to me and said, "Let’s go. Now." She turned on her heel and I followed her back the way we’d come, the river of men parting to let us pass. I could tell that someone had said something that made her realize that we weren’t welcome there; that it wasn’t safe to continue deeper into the male bastion of this market. We left that confined, crowded alley and turned onto a wide street. Only a few other women were walking about and even they were cloaked in burqas or enormous scarves.

On our way to the market, I had felt pretty safe walking on this same street, bustling with the every-day activities of vendors and their customers. Now I was nervous. Warnings to foreigners not to walk on the streets flooded my mind. My actual level of safety hadn’t changed, but my level of fear had. Mariam and I continued the few more blocks to her house without incident. We sat comfortably in her living room while her mother and sisters served us a delicious lunch of qaboli rice 6, a parsley and tomato salad, and yogurt accompanied by a plate of fresh hot peppers.