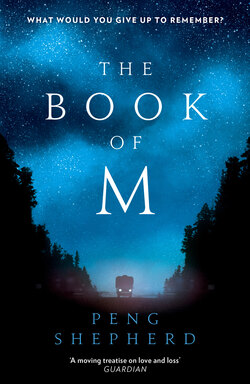

Читать книгу The Book of M - Peng Shepherd - Страница 17

ОглавлениеI CAN’T REALLY AVOID IT ANY LONGER, I GUESS. NOT TALKING about it isn’t going to change that it happened, so I might as well say something before I forget how it went. I don’t know if I believe you yet, Ory. If recording things will really make a difference at all. But if it does—well, I don’t really know what are the most important things to get down on tape yet, so I figure I should probably just say everything I can think of. Including this.

So. The day I lost my shadow.

It was two weeks ago now. Which is a pretty long time for me to still remember as much as I do, judging by past cases. Everyone’s different, though, they say. Hemu Joshi started losing his memories so quickly, just a few days in, but there were reports of some people in Mumbai who took a month to forget anything significant. I think the longest one I ever heard about before the electricity went out was about a month and a half. So hopefully I’m more toward that side of the average. These past two weeks have felt like a year, in some ways. To have a month and a half left before it all goes, it might feel like an eternity.

This is strange, talking to myself and you like this. Especially since I’m not there with you anymore. I have a confession: I actually wasn’t going to use the tape recorder, even though I promised you I would. But then I got out here, alone, and I just—it feels good to talk. It makes me feel real still.

I know I’m the one who left and that you’ll never hear this, but before I start, I want to say, just in case: Ory, if you’re listening to this—somehow, some way—it didn’t hurt. So don’t worry about that part, at least. I hardly felt it.

There was nothing about that morning two weeks ago that seemed different. I’m sure you’d say the same. I looked normal, felt normal. We split a can of corn from our dwindling cupboard supply, and then you left to check the trap and then the city. I’ve racked my brain for anything. A sign, a twinge, a premonition. But there was nothing.

After you left, I went into the kitchenette to do the counting for us. How many matches. How many shotgun shells. How many pills of found Tylenol, amoxicillin, doxycycline. I felt like a squirrel, counting how many nuts we’d managed to store in the hole in our tree to see if it was enough to last through the winter.

You know this already—the kitchenette was my favorite room in the shelter, because the window was so small and our floor was high enough up that a person couldn’t see in from the ground, so the glass there could stay uncovered. At first you wanted to block it like the rest of them, just to be safe, but I managed to convince you to leave just that one open. I don’t think you have any idea how much time I spent in that room on days you were out scavenging for supplies or skinning a mouse from our trap. Some mornings, I just lay on the floor there, sunbathing.

Sometimes, on particularly bright days when the wind was very still, two little gray sparrows would land on the branches of the tree outside that window. I think they might even have been mates. A few weeks ago, even though it was already getting cold, one of them came back with some sticks, and I was so excited that they might be building their nest there that I forgot to do anything I was supposed to do that day, which was quite a bit: I had at least three of your shirts to sew because you kept ripping the seam where the sleeve joined the shoulder, and I was supposed to repair the cardboard covering on one of the first-floor windows where it had peeled loose and was flapping against the cracked glass in the breeze. You were afraid the movement might attract passersby that otherwise wouldn’t have noticed or considered the building. I agreed that this made sense. I just completely forgot, because of the birds. We got in a pretty big fight about that when you got home, I remember. That was before my shadow disappeared and you started handling me with kid gloves. Now, when I forget to do something, you barely say anything at all, or sometimes even tell me it’s fine, that you’re just happy I’m still doing well and had a good day. But the look on your face now is so much worse. I’d rather have a hundred thousand fights than see that look on your face again. Well, I guess I won’t have to anymore.

Okay, stop being grim. I’m off topic.

I remember grabbing a jar of spaghetti sauce mid-count when I first noticed it. The strange stillness in the room. It was always so still when only I was home, but this was stillness of a different quality. It was full of something, rather than absent.

I looked down at my shadow there on the floor, and because of the light from that little window, it was perfectly stretched out in front of me. We were the exact same height and shape. There was no distortion from the angle of the sun or a bump in the floor or a wall that might have cut into the silhouette. We matched exactly. Perfectly. Down to the eyelash.

I lifted up the jar, and so did my shadow. We both leaned over and set the sauces on the counters, and returned our hands to rest at our sides. It was like I could feel that something was about to happen. Like I shouldn’t look away.

Then something did. This is going to sound absolutely crazy, but I swear it’s true.

I was holding perfectly still, under the spell of that feeling, just watching my shadow. It was looking back at me, in the same pose, waiting.

Then I saw it tilt its head ever so slightly to the side, all by itself.

There was a moment of coldness, like the entire room had dropped twenty degrees. I tried to take a breath, but I couldn’t move. Then it was gone.

I didn’t cry. Not that whole afternoon. Instead, I kept busy, taking inventory of our first-aid supplies, cleaning, making sure the window coverings were still secure, double-checking that we had sufficient shotgun ammunition, cleaning and resetting the game trap. I felt like there were so many things to make sure of, and so little time. Like it was all going to end that same night, and I’d just vanish too, forever. I kept spinning around to look behind me, to see if maybe I’d been mistaken, that the sun had just disappeared behind some clouds for a second, or I simply had cabin fever. But it didn’t matter how many times I looked or how many different directions I shone our spare flashlight on my hand. I couldn’t make a silhouette against any surface. In the light on the wall, the plastic cylinder looked like it was floating in midair all by itself, careening wildly about, pointing every which angle. As soon as I noticed, I put it down immediately. I couldn’t touch it again.

I forgot to start dinner. Instead, I shook out the winter clothes in the storage trunk so they wouldn’t have moth holes in them by the time we needed them. I still didn’t cry.

Even when I went back in the kitchen and saw that jar still sitting on the counter, and its own twin still painted darkly on the floor, I still didn’t cry.

Not until after it had gotten dark, and I heard your key in the door.