Читать книгу A Great Conspiracy against Our Race - Peter G. Vellon - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

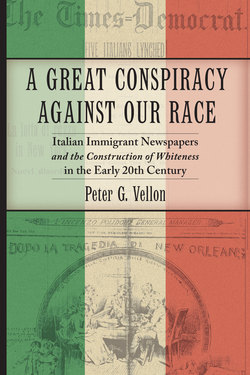

The Italian Language Press and Africa

A day after the brutal lynching of eleven Italian immigrants in New Orleans in 1891, Il Progresso Italo-Americano published a letter on its front page written by an Italian American named Marchese. Marchese expressed outrage over the cruel work of the mob in New Orleans and added that his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts, commiserated with the victims. Moreover, he expressed particular shock over how this could happen in a “civilized” nation such as America. Echoing a sentiment that prevailed throughout the Italian American press, Marchese concluded that the barbaric act of lynching might be expected in Africa tenebrosa (dark, murky Africa) but not in the United States.1 In a letter to Cristofero Colombo, another New York Italian American daily, Alberto Dini went one step further by maintaining that “not even the savage population of Central Africa would approve of such a disgraceful action.”2 According to a cynical Italian American press, the line between African “savagery” and American “civilization” became blurred: “But where are we? The only difference now between the free sons of America and the savages of Africa is that Americans have yet to become flesh eating cannibals.”3 In a scathing indictment of American lawlessness, African “savagery” was held as the standard against which to judge American society. In response to Dini’s letter, the Cristofero Colombo asserted, “At least cannibals respect the laws of primitive tribal justice so that a massacre like this would have been avoided.”4

Marchese’s and Dini’s letters reflect not only the vicissitudes of Italian immigrant topographies of race, color, and civilization in late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century U.S. society but also a transnational racial awareness. These immigrants had seen parallel issues in their homeland. Coming out of Italian unification in 1860, Italians wrestled with the task of constructing a unique Italian identity from the fractious provincial and regional identities that had characterized Italy’s history. Compared with its European neighbors, Italy suffered from high illiteracy rates, low educational achievement, infrastructure problems, and low political participation that rendered the task of nation building rather bleak. However, using the state and the military as the means through which to consolidate power, Italy’s bourgeoisie—held together by a common language and literature—used the language of patriotism to mold a nationalistic history connecting postunification Italy to a distant past. According to John Dickie, the proliferation of racial stereotypes related to the problem of the Mezzogiorno (Italian South) must be viewed within the context of upper-class and elite Italian anxiety over the probability of creating a successful nation-state after unification.5 Indeed, a critical theme informing nationalistic and patriotic attitudes disseminating within Italy’s elite classes revolved around the emerging concept of the South as a region marked by backwardness and criminality, savagery and darkness. Fused with these perceptions was the Mezzogiorno’s negative connection to Africa, especially central Africa, as the ultimate image of darkness and savagery. One of the many factors creating “imagined communities,” to borrow Benedict Anderson’s phrase, is positing a normative value to one’s version of nation by employing definitions of what it is not. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, imagined constructions of Italian identity and Italian nationhood emerged simultaneously with alternate constructions of a backward, criminal, and African South.6