Читать книгу A Great Conspiracy against Our Race - Peter G. Vellon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

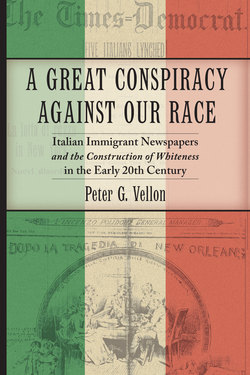

The Italian Language Press and the Creation of an Italian Racial Identity

On April 2, 1927, Carlo Barsotti, the founder and owner of New York’s Il Progresso Italo-Americano (Italian American Progress), was laid to rest in what was reported to be an exact replica of Rudolph Valentino’s coffin. In 1872, the twenty-two-year-old Pisan had arrived in the United States a poor immigrant, but by the time he died he had become one of the wealthiest and most influential leaders in the Italian immigrant community. Barsotti earned a lucrative living as a labor agent, or padrone, directing gangs of Italians on the railroads, ran as many as four lodging houses, and owned a savings bank that catered to Italian immigrants. Motivated to fill what he considered a void in the expanding Italian community, Barsotti founded Il Progresso in 1880. By 1920, the newspaper had become the most important, and largest, daily Italian language newspaper in the United States.1

Faced with incessant calls to restrict immigration based upon race, a fierce hypernationalism unleashed by World War I, and frequent violence and discrimination, historically provincial Neapolitans, Sicilians, and Calabrians found themselves united by a common antagonist. At the forefront of campaigns to uplift the race was an Italian language mainstream press that sought to justify Italian worthiness as a civilized race. The mainstream press accomplished this by focusing on italianita, or a celebration of all things Italian. Newspapers highlighted community events, defended Italians from American nativism, and sponsored campaigns to erect monuments to figures such as Christopher Columbus and Giovanni da Verrazzano and in the process contributed significantly to an emerging racial identity as Italian that had never existed in the old country.2 Despite the obvious financial and narcissistic appeal motivating prominenti such as Barsotti to trade in the discourse of nationalism, it nevertheless appealed to southern Italian immigrants faced with a nativist American environment. During the period of mass immigration, Italian language newspapers experienced explosive growth as the city swelled with immigrants and exercised a crucial role, not only in the assimilation of Italian immigrants but in the creation of an identity as Italian, American, and white.3

* * *

Italian immigrants did not arrive with a collective Italian consciousness, and the social, educational, and cultural divides that had historically separated northern and southern Italians did not disappear upon entry into the United States. The lower half of the Italian peninsula, or Mezzogiorno, was marked by a history of economic exploitation, political oppression, and cultural discrimination.4 Centuries-old problems such as uneven social arrangements and poverty-level existence relegated most of the agrarian proletariat in the South to a protofeudal existence. Although Italian political unification in 1861 did not create the problems within the Mezzogiorno, it failed to address them, and in the years after 1861 disparities between the two regions actually increased. The northern-dominated Italian government failed to include the South in public works programs, transportation improvements, educational reforms, and badly needed irrigation projects. These policies served to ensure the continued poverty of the South. Further exacerbating the situation, the central government increased taxes on the southern peasantry compelling them to bear a disproportionate share of the public debt.

During this period the notion of Italian dualism originated, and a series of powerful images permeated the consciousness of national public opinion. Illustrations of rural brigands hanging from scaffolds intertwined with stories of barbarous actions increasingly informed the image of a demonic Mezzogiorno. Many northerners viewed the South as a primitive land where the climate induced laziness, irresponsibility, and the rule of nature over civilization. The perception of the Mezzogiorno as a land forgotten by history was buoyed by powerful racial connotations intimately connected to Africa. For example, according to sociologist Gabriella Gribaudi, the “South was considered a frontier dividing civilized Europe from countries populated by savages from Africa.”5 French author Crueze de Lesser remarked in 1806 that “Europe ends at Naples and ends badly. Calabria, Sicily and all the rest belong to Africa.” In 1860, an envoy of Italy’s first prime minister, Camillo Cavour, wrote of the South: “What barbarism! Some Italy! This is Africa: the bedouin are the flower of civilized virtue compared to these peasants.”6

By the late nineteenth century, writers such as Alfredo Niceforo and Cesare Lombroso claimed to have scientifically validated southern Italian inferiority through the theories of the positivist school of biological racism. Lombroso, a noted Italian criminologist, pinpointed biological, rather than socioeconomic, reasons behind the proliferation of crime in the southern regions. Alfredo Niceforo, an Italian academic, reasoned that the moral and social structure of the South revealed an inferior civilization that was reminiscent of a primitive and quasi-barbarian age. Describing southerners as feminine, or popolo donna, and northerners as masculine, or popolo uomo, Niceforo processed civilization and barbarity through a gendered lens that served to clarify and reinforce the notion of southern Italian barbarism. Constructing a relationship between femininity and barbarity versus masculinity and civilization,7 these “scientific” conclusions only served to reinforce what northern Italians had come to accept: southern Italians were an inferior breed of savages and barbarians biologically distanced from progressive, civilized northern Italians.8 These theories had a transnational impact and influenced the anti-immigration and restrictionist forces in the United States. Indeed, in 1905, four years after Giuseppe Sergi’s The Mediterranean Race was published, the U.S. commissioner-general of immigration revised the government’s classification of Italians and began to distinguish between northern and southern Italians as two peoples. Informed by Sergi’s theories, the congressional commission charged with investigating immigration, more commonly known as the Dillingham Commission, elaborated upon this distinction and concluded in its findings, published in 1911, that Italians comprised two distinct races: northern Italian and southern Italian.9 These racial differences remained at the core of the commission’s recommendations to restrict new Italians described as a “long-headed, dark, ‘Mediterranean’ race of short stature.”

Italian Immigrants and New York City

In 1882, a total of 648,000 European immigrants immigrated to the United States, the overwhelming majority (87 percent) hailing from northern and Western Europe, while roughly 13 percent came from eastern and southern Europe. By 1907, however, the origin, as well as the perception, of the immigrant would change markedly. During the course of that year, immigrants from eastern and southern Europe accounted for roughly 81 percent (or 972,000) of European immigration to the United States. The number from Italy alone amounted to 286,000; this was more than three times the total of all eastern and southern European immigrants for the year 1882.10 The migration from Italy accounted for 17 percent of the total immigration during the period from 1880 through 1924 as 4,569,918 Italians immigrated to the United States. The influx of Italian immigrants was so staggering that by World War I Italy had been losing population to emigration at a rate of more than a half million a year.11

Focused on New York City, the epicenter of Italian immigrant life in the United States, this study will rely extensively on the most important newspapers published there during the period 1880 through 1920, when Italian migration to New York changed the face of the city. According to the 1910 census, between 1880 and 1900 the Italian population of New York City increased by 20,000 to 225,026, and by 1910 New York contained 340,765 foreign-born Italians, with the total number of people identifying as Italian speaking numbering 544,449.12 Not only did 95 to 98 percent of all Italian immigrants pass through Ellis Island, but 54.5 percent of the total in 1901 delineated New York City as their final destination. These numbers are more impressive given what was certainly an underrepresentation of these official figures due to mitigating factors ranging from Italian distrust of civic authority to congested boardinghouses and tenements.13

Italian settlements spanned every part of New York City, and where Italians decided to live was primarily influenced by proximity to employment or a desire to reunite with family or friends from their particular town or region. Every borough of New York City housed Italian immigrants; some sections contained only a few, whereas Italians constituted well over 90 percent of the population in other enclaves. By 1903, one community study revealed the only section of Manhattan that did not contain Italians stretched from 72nd Street to 140th Street on the west side of the island. Given the fluidity of these communities, population statistics cannot tell the entire story, although they can provide an important snapshot of how these communities evolved. The two most densely populated and renowned Italian colonies during this period were the areas around Mulberry Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and East Harlem, from 100th Street to 115th Street and from Second Ave to the East River. By 1918, the Mulberry Bend district housed approximately 110,000 Italian immigrants and their American-born descendants and was the largest Italian colony in New York. The next largest Italian enclaves were in East Harlem, numbering approximately 75,000, and the Lower West Side of Manhattan, numbering 70,000.14 For many, by the early twentieth century the area known as Mulberry Bend in Manhattan had become synonymous with the most visible problems associated with unfettered immigration. With the publication of Jacob Riis’s book How the Other Half Lives in 1890, for the first time Americans were able to peer into a world they had only heard about. High population density, overcrowded tenements, unsanitary health conditions, inadequate water and sanitation, crime-ridden streets, and unintelligible languages became emblematic of the foreignness of Italian immigrants within the city.15

Italians remained loyal to traditional values of campanilismo, or the desire to trust only those from their very immediate family, extended family, or town, and through chain migration settled in areas where kin or extended kin had established residency. Often this resulted in entire towns or villages being transplanted to specific streets in New York City.16 For example, the Mulberry Bend area was composed predominantly of southern Italians from Calabria, Naples, and Sicily, although immigrants from Genoa lived there as well. East Harlem, or Italian Harlem as it would become commonly known, saw much the same pattern emerge as immigrants predominantly from the South—Naples, Calabria, Salerno, Avigliano, and Sicily—filled the tenements. It was not uncommon for each street to be inhabited by a different regional population, with Neapolitans living on 106th to 108th Street and immigrants from Basilicata predominating from 108th to 115th Street.17

For Italians leaving their towns and villages, New York offered the prospect of rapid employment and economic betterment. Only 16 percent of the roughly three-quarters of the arriving Italian immigrants who labored in agriculture in Italy did so in the United States, and a 1917 study found that 82 percent of Italian-born immigrants in New York City were employed in industry.18 Although Italians were employed in skilled work, most prominently in the garment industry, masonry, stonework, and the building trades, by far the largest concentration of jobs fell into the category of unskilled.19 An overwhelming majority of Italians found employment as workers in construction, railroad gangs, mines, quarries, silk mills, machine shops, subways, and waterworks. Given New York City’s rapid expansion, Italians were well represented as laborers digging tunnels for the subway system, in the Sanitation Department, and working on projects such as the Jerome Park Reservoir and many other railroad and building projects around the city.

Informed by the same factors pushing Italians to settle among their own paesani (countrymen), immigrants started mutual aid and fraternal organizations to provide crucial services such as unemployment insurance, employment assistance, and death benefits. Men from specific towns of origin organized the clubs and offered Italians, among other things, a chance to speak in their regional dialects and in many tangible ways eased the process of dislocation. Most often, leadership reflected the larger community’s bifurcated social structure as club leaders came from the upper class. Prominenti took great pride in, and exerted much energy in, attaining titles and honors befitting men of such self-importance. These societies played a vital role in easing the transition of Italians to a new environment by reestablishing and transplanting traditions and customs from the paesi. They were incalculably more popular and relevant among first-generation immigrants than among their American-born offspring, who did not have one foot in Italy and another in the United States.20 According to the president of the Bargolino Benefit Association, a club derived from Italians from the same part of Sicily, these organizations “provided a suitable meeting place in order to avoid having members stand on street corners and about saloons; to develop socially and to be prepared to mutually assist one another in every way.”21

Early on in the immigrant experience, mutual aid societies and fraternal organizations did little to lessen the regional differences and rivalries that existed within Italian immigrant enclaves. Performing important psychological and social roles, these organizations assumed immense importance and indirectly hindered widespread collective organization, often to the chagrin of labor organizers.22 However, as immigrant colonies matured, especially after 1900, attempts at collective organization around a larger consciousness as Italians began to take hold. For example, the National Order of the Sons of Italy, created in 1905, was the first organization that began to subsume local fraternal or regional societies under a larger umbrella of federated societies and lodges. By World War I, the Sons of Italy began to wield significant power within Italian communities on the local and state levels.23 The emergence of the Sons of Italy did not replace local mutual aid societies germane to particular villages or towns, but it did coincide with the creation of an image of Italianness that did not exist in Italy. Society banquets, dinner dances, and annual religious feasts celebrated regional ties through the lens of a minority population reviled by many as unwelcome others. As such, organizations often focused on the merits of Italian culture and civilization as a means of community uplift and survival, thereby promulgating a nascent Italian patriotism. And, although by 1921 some contemporary observers such as John Mariano believed mutual aid societies and fraternal clubs prolonged a fractured Italian identity and sustained anti-Americanization sentiment, these organizations actually accelerated the emergence of a collective Italian racial identity.24

Religious observation and practice proved to be an arena where Italian immigrants did not have an easy transition. Although predominantly Roman Catholic, Italian immigrants did not blend smoothly into New York’s Irish American–dominated Catholic community. There were several levels of dissonance between the Irish hierarchy and their new communicants that for some time posed severe barriers to immigrants’ full incorporation into the Catholic parishes. Clearly, priests and upper-level church hierarchy were not immune from the prejudice and discrimination that targeted southern Italian immigrants in their new home. Italian attitudes toward priests, church attendance, doctrinal tenets, and the personal manner in which Italians worshipped God and saints were wildly dissimilar to Irish American Catholic norms and principles. During the first two decades of mass immigration, Italians remained resentful of Irish arrogance and domination, symbolized by the practice of relegating Italian parishioners to church basements for their masses. As more immigrants arrived, Italians began to form their own parishes, with some of the most notable located in the most densely populated Italian colonies: Our Lady of Mount Carmel on 115th Street in East Harlem, formed in 1885, and Our Lady of Loretto on Elizabeth Street in Little Italy, started in 1892.

By 1911, an expanding population numbering more than 500,000 had established roughly fifty Italian churches in New York City. These churches hosted the traditional religious feasts, or feste, held throughout the year, especially during the summer months, which honored local or regional patron saints and Madonnas. Although these feasts were religious in nature, Italian mutual aid societies elaborately planned and directed them under the umbrella of the clergy. During these spectacles Italians paraded ornately attired religious statues throughout the neighborhood as devotees followed along in procession. Street vendors selling Italian ice cream and roasted peanuts, musical bands playing traditional music, and firework displays earmarked the day’s events. Perhaps New York City’s most famous and well-attended feast was held at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in East Harlem, although others such as the Feast of Saint Rocco on Mulberry, Mott, and Baxter Streets in Little Italy also remained prominent. However, Italian demonstrations of folk religious beliefs did not go unnoticed by critics. Startled and dismayed by what they viewed as uncivilized and ignorant revelry, American onlookers were also stunned by how an impoverished community could afford such lavish displays.

The Italian Language Press and Its Influence

The Italian language press played a significant role in providing immigrants with the tools to navigate their new environment, and its explosive growth and fluidity mirrored the development of the Italian immigrant community of New York City between 1880 and 1920. For example, from 1884 to 1920 the number of Italian language newspapers nationally increased from a total of 7 to 98, with New York City being home to more than any other city by 1920 with 12.25 However, this did not capture the full breadth of the press’s impact as 267 additional newspapers, both radical and mainstream, were published and circulated at various times throughout this period.26 In addition to being the largest Italian colony, New York City offered advantages to the news industry not available in most other cities. With respect to successful commercial dailies such as Il Progresso, New York’s geographic location allowed the paper to tap into efficient news-gathering resources and dissemination facilities, as well as obtain the latest news from the colony or from Italy in the shortest amount of time. Published daily, Il Progresso and Bolletino della Sera became a vital source of immediate information not only for Italians living in New York but also for those outside the city and state.27

Italian language newspapers reflected the heterogeneity and fluidity of the community itself. Newspapers frequently went in and out of existence, and a majority of newspapers could not maintain a lasting circulation in order to remain financially solvent. Reflecting the community it served, the press varied in its political orientation, ranging from mainstream political identification as Republican or independent to more radical ideologies such as socialist and anarchist. The mainstream, or commercial, press enjoyed larger circulations than the Italian radical press and by virtue of subscriptions and advertising revenue usually experienced a longer life span. Some of this owed to the serious obstacles socialist and anarchist papers faced, such as fierce governmental repression that severely hampered their print operations. However, radical newspapers were no less important, often beyond what was reflected in their circulation numbers, and some maintained publication for decades.

The era of mass Italian immigration coincided with the emergence of what historian Rudolph Vecoli termed the “prominenti phase of Italian journalism” in the United States.28 The prominenti, or prominent ones, were generally Italians who had arrived early on in the migration process, knew some level of English, and established businesses that served the immigrants. Men such as Carlo Barsotti and Louis V. Fugazy owned and operated boardinghouses, neighborhood banks, saloons, or grocery stores, worked as labor recruiters and agents, or acted as notary publics, sometimes combining all of these functions. Their practices did not come without a price. For example, in addition to providing overcrowded rooms, boardinghouse owners charged exorbitant fees to hold a transient immigrant’s baggage, and labor agents, or padrones, as they were known, often sent unwitting Italian laborers into precarious situations as strikebreakers or contract laborers. However, for many immigrants who arrived without friends or relatives in the United States, and did not speak English, access to a countryman with some knowledge of the city and how it worked was a vital resource. Whether it was finding employment, transferring money to Italy, writing letters for an illiterate immigrant, or settling legal disputes among quarrelling immigrants, these middlemen became indispensable within the Italian immigrant colonies. Their capacity to render vital services and dispense patronage earned them a level of prestige and acclaim throughout the colonies that only buttressed their importance, wealth, and prominence.

For prominenti, newspaper ownership became extremely attractive as a means to advance their personal agenda and further extend and widen their influence throughout a community desperate for direction.29 Before mass immigration, G. P. Secchi di Casali, a Mazzinian exile, and Felice Tocci, an Italian financier and banker, founded L’Eco d’Italia (the Echo of Italy) in 1849. The first Italian language newspaper to appear in New York City, L’Eco d’Italia operated ideologically within an “exile mentality” and catered to a smaller, more integrated northern Italian community.30 Although the paper covered events within the scattered Italian communities, it focused primarily on news and events from Italy. Followers of Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, the paper’s editors intensely debated political and military struggles within Italy. This focus would change drastically as waves of southern Italian immigrants began arriving in New York.

By starting Il Progresso Italo-Americano in 1880, Carlo Barsotti cast the mold for big-city Italian immigrant prominenti and Italian language daily newspapers. With the help of his partner, Vincenzo Polidori, who was born in Rome in 1843, Barsotti started with a staff of two and a minuscule budget. Its office was located in the rear of the New York Herald offices on Ann Street in lower Manhattan, not far from the heart of what would soon become New York’s Little Italy. Given that neither employee could translate English stories into Italian, the paper initially resorted to clipping news stories from a Bologna newspaper and changing the dates to suit their purposes. In 1882, Barsotti hired Adolfo Rossi as editor, and the circulation increased steadily to 6,500 by 1890 and 7,500 by 1892. By the early 1890s, the paper’s masthead already proclaimed in English that Il Progresso was the most “influential Italian daily newspaper in New York and in the United States” and “had the largest circulation of any Italian paper in America.”31 During the 1890s, Barsotti would merge a smaller Italian language newspaper in New York titled Cristofero Colombo with Il Progresso.32 The paper’s circulation dramatically increased after 1900, but circulation reached its height of 175,000 copies during World War I. Its former editor Alfredo Bosi credited the success to Carlo Barsotti’s tireless work and many popular patriotic initiatives.33 By 1920, Il Progresso had expanded to eight pages and boasted a circulation reaching 108,137. A sixteen-page illustrated Sunday supplement enjoyed a circulation of 96,186. According to Bosi, the Sunday supplement was “a publication without equal … it is printed on the best machines that produce 40 copies per hour so the paper can get out quickly to anxious Italian readers across the City.”34

Attempting to build on the success of Il Progresso, Vincenzo Polidori, along with Giovani Vicario, a Naples-born attorney, established L’Araldo Italiano (the Italian Herald) in 1889. L’Araldo was published every day except Mondays and was soon accompanied by an evening newspaper, Il Telegrafo.35 The paper employed “valorous journalists” such as Luciano Paris, Giuseppe Gulino, Luigi Roversi, Paolo Parisi, Ernesto Valentine, and Agostino DiBiasi and at various times was listed as a Republican paper and other years identified as independent.36 Some historians described the paper as more balanced in its reporting than Il Progresso and more friendly to labor than its chief rival, especially after 1910.37 However, despite having a larger circulation than Il Progresso in the early part of the twentieth century, L’Araldo could not keep up with Il Progresso’s explosive growth and reached its circulation zenith at 18,000 in 1916.38 By 1917, both L’Araldo and Il Telegrafo were sold by Vicario to Il Giornale Italiano, edited by Ercole Cantelmo and part of Frank Frugone’s publishing consortium. By 1920, the paper’s circulation narrowed to 12,454 copies.39

At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, a new daily Italian language evening newspaper added to the increasing competition among New York’s mainstream newspapers. In 1898, Frank Frugone founded Bolletino della Sera (the Evening Bulletin), and his story mirrored Barsotti’s in several ways. Frugone came to the United States from northern Italy (Chiavara, Genoa) with limited means and attended night school as he worked as a printer’s apprentice. Entrenched in the prominent class by 1898, Frugone, along with Agostino Balletto, founded and edited Bolletino. According to the New York Times, Frugone’s editorials aided many Italians by advocating for immigrant protection laws, and in 1912 he offered his testimony to the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in an effort to prevent passage of a literacy test for immigrants. Frugone was active within the Italian immigrant colony as treasurer of the Italian American Educational League, president of the Italian Vigilance Protective Association and Dante Alighieri Society, as well as participating in political and cultural associations and organizations in New York such as the National Republican Club and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Frugone remained active in politics and tried unsuccessfully to parlay his influence into a congressional seat in 1904 and 1906.40 Running as a Republican in 1906, Frugone received the endorsement of the New York Times over his Tammany opponent. “Although he is of Italian birth,” the Times stated, “Mr. Frugone has spent most of his life in this country, where by his own industry, his talents, and his good character, he has risen to a position of influence as the editor of a prominent Italian newspaper, and as a man who is respected and esteemed and listened to by men of his own race in this country.”41

Bolletino published daily, except for Sundays, and used a four-page format. The paper featured journalist Bernardino Ciambelli, who Alfredo Bosi called “one of the most popular colonial journalists.”42 By 1911, the newspaper had increased to eight pages and had a circulation of 42,000 copies.43 Bolletino della Sera was part of the Italian commercial press and advertised itself as Republican in political orientation. Historian Edwin Fenton remarked that, unlike Il Progresso, Bolletino gave extensive coverage and support not only to socialists but also to the American Federation of Labor in its fight against syndicalists, especially from 1908 through 1920.44 By the early 1920s, Bolletino della Sera had a circulation of approximately 75,472 and catered to a readership of “workers in various industries, laborers, miners, farmers and business men.”45

Throughout the period, many mainstream newspapers came in and out of existence that did not possess the circulation numbers of Il Progresso or Bolletino yet were influential nonetheless. In 1910, Italian scholar and author Alberto Pecorini founded and edited Il Cittadino (the Citizen), a newspaper issued by the Civic League Publishing Association. The paper was published every Thursday and was identified as having an independent political orientation.46 Pecorini published prominently in Il Cittadino, often using the front page to inform Italians, as well as English-speaking Americans, of issues and events important to both. In a section titled “To Our American Readers,” Pecorini offered substantive discussions and editorials on topics such as Americanization, citizenship, immigration restriction, and literacy.47 These topics were well represented in books he authored such as Gli Americani nella vita moderna osservati da un italiano (The Americans in modern life observed by an Italian), published in 1909, and La Storia dell’America (The history of America), a concise history of the United States intended for use in Americanizing Italian immigrants, which he published for the Massachusetts Society of the Colonial Dames in 1920.48 Il Cittadino was published for ten years and was widely respected by American readers as well as by English language newspapers such as the New York Times, which labeled it “one of the best of the city’s foreign language papers.”49

Although mainstream newspapers dominated circulation within the Italian immigrant colonies, radical or sovversivi (subversive) publications rivaled their intellectual grip on the community.50 Championing class struggle and class consciousness, radical newspapers contained political theory and consistently reported news of labor activities and strikes. Italian language newspapers not only tried to connect workers with employers but also often functioned as their protectors. Especially in radical newspapers, numerous articles detailed the scurrilous practices of American employers and Italian labor bosses, alerting Italians to strike activities and employer exploitation around the country.51 For example, religious festivals such as those at Our Lady of Mount Carmel in East Harlem were harshly condemned as sad spectacles where the church and prominenti padded their own pockets with the hard-earned wages of ignorant and exploited Italian workers.52

Radicals in turn created an oppositional culture and celebrated their own holidays, such as May Day (Primo Maggio), and their own heroes such as Gaetano Bresci, the anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I of Italy in 1900. In addition to picnics, theater, processions, and other community-building activities, the press became a critical tool for spreading the message. Although radical newspapers did not carry commercial advertisements, their existence was mercurial, and frequently papers would meander in and out of circulation under different titles. However, even in the face of daunting obstacles such as financial insecurity and state and federal repression, radical newspapers persisted and were extremely influential.53

Il Proletario (the Proletariat) originated in Pittsburgh in November 1896 and by 1902 had become the official organ and mouthpiece for the Federazione Socialista Italiana del Nord America (FSI; Italian Socialist Federation of North America). The paper started as a weekly and promptly went out of business in 1897 due to lack of funds, but it soon was resurrected in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1898. Borrowing a method utilized in Italy to maintain solvency, the paper organized a donor list and moved to New York in 1900 to merge with Giovane Italia. Giacinto Menotti Serrati, born in 1874 in the northern Italian region of Liguria, assumed the editorship of the newspaper in 1902 and on May 1, 1903, turned it from a weekly to a daily. However, although Serrati had collected $4,100 by early 1903, he needed twice that amount to operate the paper. Due to financial concerns, the paper returned to its weekly status in January 1904 and ceased publication six months later. Although the paper did not publish exclusively in New York, it was headquartered there for some time, as well as in other northeastern cities, until moving to Chicago in 1916. This socialist newspaper and many other Italian radical newspapers were, in the words of Robert Park, “mendicant journal(s). They are either regularly supported by the parties and societies they represent, or they are constantly driven to appeal to the generosity of their constituency to keep them alive.”54

In 1904, Carlo Tresca, noted radical and labor organizer, arrived in the United States and assumed the editorship of Il Proletario.55 Tresca, who was born in 1879 in the southern Italian region of Abruzzi, revived the paper and was instrumental in rooting Il Proletario and the Italian socialist movement within the broader American labor struggle. Migrating from Italian-centered dictates and aligning more closely to the doctrines of revolutionary industrial unionism, Tresca saw the value of using the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) as the vehicle to push Italians beyond their own provincial worldviews and establish them within a larger, class-based movement. According to Bruno Cartosio, Tresca was the one who “really transformed Il Proletario into an Italian-American newspaper.”56

The fortunes of Il Proletario reflected the twists and turns within the Italian socialist movement during this period. An ideological split emerged between those who viewed the IWW’s revolutionary socialism as the path toward class liberation and moderates who wanted to work within the American socialist movement. In 1907, Giuseppe Bertelli left his editorial position at Il Proletario and started his own newspaper in Chicago. Although Il Proletario and the Italian socialist movement suffered from consistent infighting, from 1909 through World War I, Il Proletario reached the height of its influence and circulation. This period coincided with a maturing working-class activism, the rising influence of the IWW, and the prominent role played by Italian workers in that struggle, especially in northeastern industrial areas such as Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Paterson, New Jersey.57 During the repressive period of World War I, legislation such as the Espionage Act, the Sedition Act, and the Trading with the Enemy Act made it possible for the Department of Justice and the U.S. Post Office to suppress any publication the federal government deemed subversive. Il Proletario was forced to move its headquarters from Boston to the IWW headquarters in Chicago in 1916. Ironically, it was during this period that Il Proletario reached its high point in circulation at 7,800 copies.58 Along with the IWW, Il Proletario came under intense government scrutiny as its offices were raided, its mailing privileges denied, and its editor, Angelo Faggi, was arrested and deported to Italy in 1919. The newspaper resumed under the title La Difesa, after the war became Il Nuovo Proletario, and in 1920 published again under the original masthead of Il Proletario. Although the newspaper would continue to publish for almost two decades, its lack of strong organizational support reflected the chilling effectiveness of repressive antilabor campaigns.59

Along with Italian socialists and syndicalists, Italian anarchists were at the vanguard of the American radical movement. Within the silk mills of the industrial city of Paterson, New Jersey, existed a prominent history of Italian radical politics dating back to the 1890s. With the migration of Italian anarchists in the 1880s and 1890s, Paterson would become home to one of the most important anarchist groups formed throughout the country. The enclave was composed mostly of northern Italian immigrants employed predominantly as skilled weavers and dyers. Anarchists formed the Il Gruppo Diritto all’Esistenza (Right to Exist Group) and along with French and Spanish anarchists helped establish Paterson as a major center of anarchist activity in the Northeast. In 1895, Pietro Gori, the Sicilian-born anarchist, playwright, and activist lawyer who moved to Tuscany at an early age, founded La Questione Sociale (the Social Question) along with Catalan anarchist Pedro Esteve.

In the late 1890s, Il Gruppo Diritto all’Esistenza had a membership of between 90 and 100 people that would soon increase to anywhere from 500 to 2,000. La Questione Sociale had become one of the most important newspapers of Italian American anarchism in the United States, with a circulation that reached 1,000 copies locally. These numbers were quite large for a community of approximately 18,000, especially when the readers’ families are added to the original 1,000. In addition, 2,000 copies of the paper were distributed to anarchist groups around the United States, as well as internationally. Some of the most important voices in the Italian American anarchist movement, such as the aforementioned Pietro Gori, Giuseppe Ciancabilla (born in Rome), Errico Malatesta (born in the province of Caserta, southern Italy), Luigi Galleani (born in Piedmont), and Ludovico Caminita, served as editors of the paper. In March 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt and Mayor Andrew McBride of Paterson ordered postal authorities to bar La Questione Sociale, claiming that the paper published immoral content that violated obscenity laws. In 1909, the paper was resurrected as L’Era Nuova until federal raids forced it out of business in 1917. Major setbacks in strike activities, especially the 1913 textile workers’ strike in Paterson, as well as the onset of World War I, redirected the paper’s focus to other issues such as the arrest of radicals and the socialist role in alleviating the plight of workers.60

Uplifting the Race in the Pages of the Press

The Italian language press provided an institutional framework for the cultural transformation of the Italian immigrant population and the development of a collective Italian identity as American and white in the United States. In conjunction with an exploding Italian population in New York City, Italian language newspapers addressed multiple needs and facilitated immigrant orientation to new surroundings. According to historian Rudolph Vecoli, the press “took on an importance [it] lacked in the old country.”61 For example, Il Progresso published classified employment listings on its front page that sought “twenty bricklayers” to work on Spring Street in downtown Manhattan or women to “cook, clean, and iron for a good salary,” stipulating that speaking English was not necessary.62 The second page of the standard four-page format featured news from communities in and outside New York, where readers could find a “detailed report of the crimes, feste, arrests, and other prominent features of the local life.”63 Moreover, articles and notices detailing the numerous dinner dances, meetings, and religious feats sponsored by the many Italian immigrant societies also appeared on this page.64 This news kept Italians connected with kin or paesani who may have settled elsewhere, whether in East Harlem, Brooklyn, or even Chicago, and chipped away at regional identities in favor of a more national collective consciousness as Italians.

However, in addition to providing tangible services such as employment listings and announcements of neighborhood events, newspapers served as a construction site for multiple campaigns to manufacture, assert, and defend the Italian race. The first page of daily newspapers usually reserved three to four columns for news from Europe, specifically Italy, and the other half for news of the day from the United States. Amid negative American perceptions, dislocated Neapolitans, Calabrians, and Sicilians yearned for any news from Italy and were especially attentive to colonial ventures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Ethiopia and Libya, as well as a series of natural disasters that ravaged parts of Italy. Prominenti such as Barsotti capitalized on these unfortunate events by initiating subscription drives to raise money for earthquake victims, as was the case in 1887, 1905, and 1908 when earthquakes ravaged different parts of the mainland and Sicily.65 In total, Il Progresso sponsored nineteen relief funds between the years 1886 and 1920.66 Seeking to enhance the newspaper’s, as well as their own, prestige within the community, editors published subscription lists—complete with donors’ names—prominently on the newspaper’s front page.

According to historian George Pozzetta, prominenti such as Barsotti were masters “at squeezing contributions for ‘worthy’ causes” and were quick to take “offense at any action that besmirched the Italian name.”67 However, although Barsotti’s actions appeared motivated by a desire to enhance his own status as prominenti par excellence rather than elevate the profile of Italian immigrants, in many ways he achieved both. Barsotti launched incredibly popular fund-raising drives in the paper and was largely responsible for the monuments dedicated to Verrazzano, Dante, Columbus, Garibaldi, and Verdi that were erected across New York City.

In addition, prominenti-defined national celebrations such as Columbus Day every October and the anniversary of the fall of Rome to the armies of united Italy on September 20 garnered frequent attention every year. Columbus, especially, served as an important symbol of an emerging Italian identity. Although the first Columbus Day parade can be traced back to 1792, the myth and imagery of Columbus would take on very different and specific meanings for the masses of Italian immigrants that arrived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.68 It was not surprising, then, that Carlo Barsotti spearheaded the effort in 1892 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas by organizing a subscription drive through his newspaper. Resulting in the construction of Columbus Circle on Fifty-Ninth Street and Eighth Avenue, this example of racial uplift publicized through Il Progresso helped nurture a maturing Italian identity among Italian immigrants.69

Moreover, newspapers such as Il Progresso remained unapologetic about defending Italians from accusations of inherent criminality, or expressing outrage over their victimization at the hands of lynch mobs. In 1891, for example, Barsotti raised more than $500 through his newspaper subscription drive for the defense fund of those Italians accused of murdering New Orleans police chief David Hennessey.70 Newspaper owners also championed causes perceived to be in the best interests of Italian immigrants and lobbied to have the Italian language taught in New York City public schools. According to Il Progresso, “Nine-tenths of the children of Italians born in America and those who arrived at a tender age without a teacher to teach them their language or their patriotic and religious traditions end up ignorant of the slightest knowledge of their country of origin.”71 Led by prominenti, Italian immigrants viewed the adoption of Italian into the New York City schools as a measure that validated their race and culture as worthy of American respect. In 1906, Il Progresso exclaimed that the introduction of Italian “was a great moral victory following years of struggle for the Italian community of New York,” reflecting not only the emerging prominence of Italians as an interest group but, more importantly, “the growing appreciation of the American public for our community.”72 Since the majority of southern Italian immigrants spoke only their own regional dialects rather than a standard Italian, the emphasis on the Italian language, and what it represented in this new and often hostile environment, helped forge a group identity that did not exist in Italy.

Historians have noted the importance of the Italian language press in facilitating an ideological shift among immigrants from a more provincial worldview as Neapolitans, Calabrians, and Sicilians to a collective identity as Italians.73 This transition has been described, often negatively, as one that postponed the assimilation of Italians into American society. With constant appeals to Italian nationalism and frequent displays of Italian pride, many have asserted that men such as Barsotti sought to keep immigrants isolated and dependent upon their own patronage as a means to maintain their power and control. Indeed, seeking to extend their influence and exposure as community leaders, former padrones, bankers, and lodging house owners perceived newspaper ownership as a powerful vehicle to accomplish these goals. To realize the full impact of Italian language newspapers, however, one must peer beyond the retrograde intentions and narcissistic impulses of Italian immigrant community leaders. And, although historians such as Rudolph Vecoli have wisely noted that Italian immigrants were not simply acted upon, but decided for themselves what was reality, to ignore the power of newspapers to shape or create the rubric of debate is untenable.

These men were so concerned with their influence and public image that internecine battles among newspaper owners, often fought within the pages of competing papers, spoke to the stakes at hand in enhancing one’s power and prestige within the colony.74 The rivalries became so heated that certain newspaper owners openly accused one another of fraud and embezzlement within the pages of major papers.75 In 1917, George La Piana sarcastically chided newspaper owners for the continual rancor that accompanied their publications. He noted how each owner proclaims the other “a bunch of thiefs [sic], that they escaped from an Italian prison which was the college where they received their education, that their sense of honor is below that of the animals, that their heads are empty boxes where can be written ‘nobody home’ and so on.”76 Some mainstream newspaper editors, such as Alberto Pecorini, lashed out at prominenti for intentionally failing to provide adequate information to foster Italian naturalization and adaptation. For Pecorini, prominenti simply preyed upon immigrants to advance their own power and prestige. Writing in the journal the Forum in 1911, he advised Italians to become American citizens and “take away the direction of their interests from the dealers in votes.” The debate reflected divergent strategies over how Italian immigrants should assimilate into American society. Pecorini believed Barsotti’s self-aggrandizing focus on the feats and accomplishments of the Italian race only served to strengthen prominenti influence within the community, further isolate immigrants in ethnic enclaves, and dangerously delay American acceptance of Italians. The New York Times agreed with Pecorini’s assessment and stressed, “We do not want foreigners in this country who are taught not to adopt American customs and ways, who do not come here for permanent settlement and citizenship.”77

Another way to measure the influence of prominenti-run newspapers within Italian colonies is to look at the vitriolic diatribes emanating from the Italian radical press. Socialists and anarchists dedicated considerable space in their publications to some of their most loathsome attacks against prominenti, who along with Catholic priests were defined as a two-headed oppressor intent on increasing their personal power at the expense of Italian immigrants. To radicals, Barsotti’s and Il Progresso’s message translated into antiworker, antiunion, and pro-capitalist. The frustration radicals demonstrated over working-class acquiescence, and in some ways deference to prominenti within the community, underscored the impact and influence of these men upon the colony.78 However, imperceptible to Pecorini, and even Barsotti and Frugone at the time, was how the Italian mainstream press’s defense of Italians and Italian civilization would prove critical to establishing a collective identity as Italians. Rather than retard immigrant acculturation, uplifting the race afforded Italians a platform from which to proudly argue for their full inclusion in American society as Italian, American, and white.

As Todd Vogel states with respect to the African American press, “A periodical analyzed as a cultural production creates an ideal stage for examining society…. In this way, the press gives us the chance to see writers forming and reforming ideologies, creating and recreating a public sphere, and staging and restaging race itself.”79 During mass immigration, Italian language newspapers emerged out of necessity to fill a crucial void in the lives of an ever-increasing stream of settlers. Whether reporting on events in Italy, organizing subscription drives for Italian earthquake victims or memorials to Italian heroes, publishing employment advertisements, or providing information about labor organizations, the Italian language press catered to its consumers and offered a life preserver for many Italians grasping for normalcy in their new environment. According to Robert Park, along with city life, mainstream newspapers such as Il Progresso served to break down the “local and provincial loyalties with which immigrants arrived, and substituted a less intense but more national loyalty in its place.”80 Implicit in this process, Park stressed, was the importance of the press in fostering, or creating, a hybrid identity, “neither American nor foreign, but a combination of both.”81 Italian language newspapers played a pivotal role in this process by forging an unique class- and race-based identity centered upon an exalted civilization rooted in an Italian past wiped clean of sectional discord and questionable racial and color status.