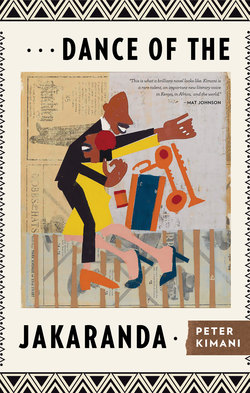

Читать книгу Dance of the Jakaranda - Peter Kimani - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

God’s Country was how Reverend Turnbull described the land in 1893 when he wrote his first pastoral letter to the mother church in England. He wrote about the marvels that he had witnessed during his travels—from the gentleness of the sands on the pristine coastal beaches, to the stunning lakes that seemingly appeared out of nowhere in the middle of forests, to the dramatic plunge of what European geographers had named the Rift Valley.

Although the natives do not know God, the perfection of their land raises serious doubts as to how this could have been created by heathen deities, Reverend Turnbull confided in his letters. What he failed to elaborate on was whether or not it was his mere presence that elevated the heathen land to God’s dominion—but then again, it was pointless to state the obvious. In that age, God and the white man were one and the same; in fact, even the locals had an expression for it: Muthungu na Ngai no undu umwe.

When Reverend Turnbull started preaching in Nakuru, he liked to refer to his mission as God-ordained, for he was not destined to be there in the first place. He used the locals’ idiom of the train as a snake to recall the story of Jonah, God’s servant who had defied His call only to be swallowed by a whale and spat out in the city of Nineveh, where he was meant to be in the first place to spread the word of God. Reverend Turnbull told his congregations that Nakuru was his Nineveh, where he had emerged from the belly of the iron snake.

The Nineveh narrative was a white lie. Reverend Turnbull simply appropriated a line that Master had used to describe the dramatic events that followed upon reaching Mombasa to commence his return trip to England. The letter of Master’s discharge from the colonial service was there all right, but it contained an unexpected gift. He had lobbied heavily for a knighthood for his service to the empire, and the letter from London indicated his bosses had acquiesced to his request and had granted him a title. But when the letter elaborated upon the details of his title, he realized his was a different kind altogether: it was a title deed to a parcel of land of his choice, anywhere in the colony. The only condition was that the portion of land had to lie between two natural boundaries for easy demarcation.

Master instantly recognized this as a bureaucratic slip that would be corrected in due time. But since he was already attached to the land, he saw it as his chance to kill two birds with one stone; he would accept the land, but this would not stop him from pushing for knighthood. He remembered the breathtaking hot water spring and the lake in the Rift Valley, and he decided that would be the land he would claim. Reverend Turnbull offered to accompany him on the trip back to the valley.

“This is your road to Damascus,” Reverend Turnbull intoned, to which Master replied, “Feels more like that Nineveh fellow, reverend.”

“Jonah?”

“Yes, Jonah must be his name. Here I am in the belly of what locals call the snake, destined for England, but fate conspires to return me to the African wilds.”

Reverend Turnbull smiled and touched his collar, and said, “I hear you,” which was his way of saying he had deferred participating in the conversation because he was distracted by a pressing thought. He was thinking Nineveh sounded both profound and spiritual. He committed it to memory for future use.

“You can build Sally a house,” Reverend Turnbull said to Master when they arrived in Nakuru. “A castle between the spring and the lake.”

Master thought that would be blasphemous but he did not voice his concern—building a house between two marvels of nature was like challenging God’s creation.

It was the talk about the Indian who got away, the one who Master was reticent about, the one whose child Reverend Turnbull was raising, that helped clarify things.

“God says we should love our enemies, and He has brought you close to the Indian to test your faith,” Reverend Turnbull said, adding immediately: “Build Sally a monument to love like that beautiful building in India . . .”

“The Taj Mahal,” Master said triumphantly, as though the sheer intensity of feeling would somehow will such a majestic building into existence.

“And those Indian workers must know how to build such monuments.”

“Technically, they are still under my command,” Master reminded.

“Then command them to action!”

* * *

The legend about the house that Master built is that the construction went on for so long that babies born during that time were toddlers when the work was completed. Others said construction went on around the clock, with shimmering lightbulbs suspended off the trees to illuminate the workers’ paths at night. Yet other villagers claimed they slept one night and woke up the following morning to find the towering structure sneering down upon them.

But the reason Master became a legend in his own lifetime was because of what happened with the house. Soon after its completion, the windows of the Monument to Love were shuttered so that no light streamed in as Master mourned and villagers whispered of the loss of his mysterious love, who had dropped him like a piece of hot ugali. Some villagers disputed this, saying it was impossible for one to hide that long, burrowed like a huko—a rodent—and devised ways to test if anybody was home. A typical test entailed picking wild eggs from the lake that gave the township its name, letting them cook in the hot water spring, and then hurling them at the wooden shutters. Cooked eggs, the villagers said, bounced off better than raw ones, their intention being not to defile the building but to rouse the aggrieved Master—ngombo ya wendo, or the love slave, as they nicknamed him—from his slumber. Nobody appeared, so they concluded that Master was no more.

Then one day, as a gentle sun rose in the east, the shutters were flung aside, the windows slid open, and throaty shouts were heard to mark the reopening. Master had overcome his grief, but only after issuing a decree of a most intriguing nature: he posted notices around the property warning that females caught trespassing on the land would be shot on sight. He and women were done, kabisa. But since very few locals could read at all, and those who did were protective of the white man, it was hard to tell which aspects of Master’s life and the house that he built were fact and which were fiction.

What happened for a fact is that Master turned his castle into a farmhouse and brought in dairy animals. He patrolled the large expanse on horseback watching his animals graze. This was a downgrade, as Master had spent years watching over humans at work and, like Jesus, rode a mule. The mule was preceded by a zebra, whose mouth was muzzled to ensure it did not bite Master. The dairy animals, beautiful in their brown, white, and black skins, grazed with white pelicans perched on their backs who watched as they mowed grass. Imagine an uninterrupted stillness of bovine bliss, the low hum of munching animals enhanced by whistling thorns in the distance. The stillness is broken by the muffled sound of a cow scratching where a tick has attached itself, but even that seems to be part of the natural ambiance. A pelican in soundless flight from the muscle twitch of its host, before relanding, the soft drops of dung at calculated intervals opening a floodgate of urine.

An electric fence surrounded the farm, dividing the animal kingdom. Wild animals that often streamed to the nearby watering hole would be jolted to their senses whenever they touched the fence, and most learned to keep their distance. By dusk, if the dairy animals had not been milked, their udders would swell and the drip-drop of milk from their teats would grow into a steady trickle, soaking the black-cotton soil to evoke notions of that ancient land where milk and honey flowed.

The wild animals watched the milky spectacle but none dared to touch the fluid, even when it formed a rivulet and coursed beyond the fence. They had the sense to stick to the pond water that they knew. A deer would mount another after quenching its thirst, which appeared to trigger other thirsts, while the hyena, convinced that Master’s arm would fall from its rapid swings, stalked him on the other side of the fence, giggling at the prospect of a meal that never materialized. The giraffes would trot through the brown savanna, and the zebras, with their black-white zigzags, brayed for Master’s attention, yearning to cross the line and leave the wilderness for his domestic dominion.

But that was before a plague wiped out the entire dairy herd yet afflicted none of the wild animals; they appeared to thrive through that period of strife.

The farmhouse was turned into a private club where white men in wide-brimmed black hats and knee-high boots sat in high-backed seats and waited, with guns at the ready, for wildlife streaming to the watering hole. They seemed to begrudge the wild animals for the plague that scuttled the Pipe Dream, as Master had called his grandiose plan to lay pipes across the country and supply milk in place of water. There would be plenty of milk for all to drink, Master had declared; even natives would have enough to drink and wash their dark skin if they so desired—it might just whiten them.

After the plague, men and, increasingly, women arrived to the shooting range and placed bets. With the carousing that went with the shooting, seldom were hands steady enough to make a proper shot, especially if it might interrupt the mating animals. As if on cue, the humans would try similar antics, reaffirming that years under the sun had not wiped out their primal instincts. The shooting range gained a whole new meaning.

* * *

Master’s real name was Ian Edward McDonald, but there was nothing real about his identity. He could as well have been Wasike or Wanyande or Wainaina, as he fluently spoke the local languages. But since he privately enjoyed the sobriquet Master, he neither protested nor affirmed its usage. And there was nothing unusual about his name, for even the colony that he had come to serve for God and country had no solid name. It was called the British East Africa Protectorate before it was christened the Kenia colony. In June of 1963—six decades after the construction of the Monument to Love—the country would gain yet another name: Kenya. And the house that McDonald built out of love would be conferred with yet a new name—the Jakaranda Hotel—immortalizing the jacaranda trees he had planted for his love, Sally. By then the trees had long wilted, just as his mysterious love had long dried up, but the passage of time had only served to renew the memory and enhance the mystique of Master’s Monument to Love.

And while Master’s house accumulated many stories over the years after its construction, it wasn’t actually the first building in the area. Babu Rajan Salim, the Indian briefly famous for fathering the child that Reverend Turnbull raised, was the first settler to arrive by the lake, although his modest rondavel was not as prominent a landmark. Not being visible is not the same as not being there, he often reminded his Indian workmates who said McDonald had built his edifice to spite them. Africans arrived later and built their huts on the other side of the lake to complete the triumvirate of hostilities that had originated on the seashores of Mombasa, hundreds of miles away, when the construction of the rail had begun. And as Reverend Turnbull liked to remind any who would listen, the sins of the fathers would be visited upon their sons a thousand times. Local elders, too, had their own proverb. They said, Majuto ni mjukuu, which meant children would pay for the sins of their forebearers.

And so it came to pass that a sixty-year grievance between two old men—one brown, Babu; and one white, Master—fell onto Babu Rajan Salim’s grandson Rajan. And in keeping with the tradition of the monument, it all started as a quest for love.