Читать книгу Dance of the Jakaranda - Peter Kimani - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

In 1902, shortly after Master’s Monument to Love had been built, Sally did make a trip to Nakuru, and experienced firsthand how the town got its name. As she hoisted a leg up to board the carriage which had been sent to fetch her, a cheeky whirlwind, ngoma cia aka—or the female demons, as locals called it—picked up pace and swished her skirt this way and that, before knocking her hat off. When Sally bent to pick up the hat, the wind blew her long, flared skirt up and over her head, exposing her hindquarters that resembled a Maasai goat’s—if you ignored the cream drawers that resembled her light skin.

The African servants who had been sent to fetch her had the good sense to flee for dear life, fearing they might somehow be implicated in the ignominy. While they may not have conspired with nature to embarrass the English woman, seeing her nakedness carried with it a tinge of violation. After all, muthungu and God were one and the same. That’s the story locals liked sharing while devouring mounds of food, although the connection between the whirlwind and Sally’s naked truth and her rejection of Master, as most still called McDonald, was never quite stated outright.

But in a land where myth and history often intersected, what happened to the woman of England is uncertain. What’s more certain is that McDonald vowed he would never speak to another woman after Sally rejected him—for the second time.

* * *

The first time Sally left McDonald was preceded by a confrontation in South Africa, his last station before his British East Africa Protectorate posting. It was early morning. He had returned home unannounced to retrieve a diary he had forgotten. He had left Sally in bed, perhaps staring into space, picking her nose, or doing those things that most housewives did before they could summon up their energies to rise and face another day.

For Sally, there was nothing to face, save for the sun that she shielded herself from by wearing a sombrero as she cut flowers from her lawns maintained by a full-time gardener, hands gloved against the prick of rosebush thorns. One could tell the progress of Sally’s day from the trail of cups. The cup beside the bed was for the early-morning tea, taken in her nightdress, feet thrust in frog-shaped warmers, while leafing through a magazine bearing big images of thoroughbred dogs. The cup by the window was for the ten o’clock tea, consumed behind dark glasses or drawn curtains while admiring Table Mountain. The cup at the dining table was for the prelunch drink, consumed with a slice of lightly buttered whole wheat bread. The jar of butter was a locus of vicious warfare between Sally and McDonald: he liked the butter surface smooth and gentle; she liked to use the blunt edge of the knife, leaving ugly marks. To McDonald, this reflected the tangled mess of Sally’s life that he was fated to deal with. Smoothing out the butter became one of the many chores in his daily routine.

The cup by the balcony was for four o’clock tea, taken with biscuits or fruit. This trail of teacups wouldn’t be collected by their servant until Sally went out for her evening walk because she did not like her solitude to be interrupted. Solitude was the reason she gave for postponing motherhood.

“I can’t handle children,” she said earnestly. “Running noses and wet bums I can, but not the cries from toothless gums.”

McDonald had long taken note of the trail of cups but voiced no concern. Like the wise soldier he considered himself to be, he had learned to pick his battles wisely. So on that fateful morning, afraid to disturb Sally’s peace, he sneaked quietly into the house to collect his diary. He was tiptoeing out when he heard a moan from the bedroom. He paused and cocked his head. He heard another moan. It sounded like pleasure, and he doubted that Sally could have derived that from the big-eared thoroughbreds in her magazines. He made his way to the bedroom door, silently opened it, and entered. Sally’s face was not burrowed in some magazine as he suspected; actually, he couldn’t even see her face—the view was blocked by the back of a head he found eerily familiar.

He could see that it was a man’s neck, sinewy from his present labors and engaged enough in his task at hand not to sense McDonald’s presence. McDonald realized it was his black gardener; he had seen the man strike a similar pose as he worked—fondling soil to pick out a weed or pruning the bushes. Now he devoted similar attention to this chore, and for a while, neither the man nor Sally noticed McDonald. When Sally finally did, and screamed, the black man thought she was screaming because of something he had done, so he continued on. It was only when McDonald dropped his diary, his trembling hands unable to hold anything, that the man realized the intrusion. Where does a man hit another to inflict the most pain, without injuring one’s ego that the invader’s very presence under his roof seeks to quash? McDonald appeared hypnotized by the puzzle, much the same way vermin are dazzled by the sudden burst of light when emerging from a crack in the furniture. McDonald’s soldierly instinct was to cut off the offending organ, but he had no idea what he’d do with it. A soldier had to envision a whole operation before setting forth. Should he throw it to the dogs? Keep it as a memento? He didn’t even have a weapon in hand. Perhaps he could use his teeth, but that would intimate a certain rage. He wasn’t a savage. Yet.

He obviously did not approve of the man’s presence in his bed, but his training taught him to keep emotions out of his work. That’s why guns had been invented—to create distance between assailants and their victims. He tried to catch a leg, but the man was as slippery as a fish. He noted how feminine the man’s shin felt, bereft of hair or scars. McDonald was determined to leave a lasting mark.

He dashed out of the bedroom to retrieve a weapon from his bag in the sitting room, but quickly remembered it was in his rickshaw waiting outside. He was losing crucial time, so he sprinted back to the bedroom, only to find that the man had disappeared out the window. Sally had gathered herself and was sitting on the edge of the bed, downcast.

For several long moments, he glared at her, trembling with anger as well as the fear of what he was contemplating. He slapped Sally once, and being a soldierly slap, it left a buzzing sound in her ear.

When he was confounded, as he was then, words utterly failed him. And when he finally spoke, it was neither a personal rebuke nor a remonstration. “Even if you have to do these things, don’t you want to be respectful of the law?” McDonald glared, before walking away. It was a useful reminder that under the apartheid laws in South Africa, miscegenation was outlawed, so Indians, blacks, whites, and coloreds were prohibited from mating outside their own races. While the statement conveyed McDonald’s allegiance to the law, it was also his way of saying: You can do what you want to do, but surely not with blacks.

The incident was not discussed any further; they were giving each other what Nakuru folks liked to call “nil by mouth.” Neither uttered a word to the other, McDonald humiliated into silence because there was no way he could broach the topic without raising doubts about his abilities as a man. After all, his wife had not been caught stealing food or clothing; she had steered her servant, her black servant, away from the flower beds to her own bed, to perform a role that McDonald had either failed to do or had not performed to her satisfaction. Sally, on her part, remained silent because she had lost hearing in one ear and was too upset to talk anyway.

So McDonald had seen his posting in the new colony of British East Africa as an escape from personal turmoil and humiliation. Perhaps he and Sally would even have another shot at their troubled marriage.

I shall be the lieutenant of the entire province, he had written to her. With a dozen servants at my disposal so even when I cough, one is likely to check if I had called for him . . .

Sally’s response had been terse: Even if you were the governor, I’m not going anywhere with you, now or in the future.

Sally, whose rich background and royal roots had been a permanent source of ridicule from McDonald’s peers, said she would remain in England for the rest of her life. He then prevailed upon her not to file for divorce—to give them a bit of time to review things.

McDonald then resolved to do what he knew best: work hard and earn a decoration for his service to Great Britain. Sally would be proud of him, he mused to himself, perhaps she’d even harken his word. If he was knighted, he would be a man of title, just like her father. That’s what motivated him to go to East Africa—to head the project that even his bosses in London admitted was a little insane. Its London architects called it the Lunatic Express, wondering where the rail would start and where it would end, for nothing of value was to be found in the African wilds. But it had to be done, and McDonald had fully committed himself to the idea that the construction of a railroad across the African hinterland was his route to self-affirmation and validation. But soon after he arrived in the marshes that grew into Nakuru town, few locals believed he was anything but completely nuts.

* * *

Ian Edward McDonald’s Years of Solitude—as his four-year seclusion came to be known in Nakuru lore—far surpassed the few hours that Reverend Turnbull was reportedly in the belly of the iron beast, and, if one were to allow his mythical parallel, the three days Jonah spent in the belly of the whale. And even the forty days and nights that Jesus spent in the wilderness. But where myth and history often intersect, and the past often collides with the present, it is imperative to clarify the circumstances surrounding McDonald’s house and Sally, the woman for whom it was built. For one cannot talk about the Indian singer Rajan, the love slave, without talking about the original ngombo ya wendo, since the two narratives both start and end at the place: the house that McDonald built—set between a hot spring and a cool lake—which ultimately became a site of unseemly arguments and simmering loves. To absorb the full story, one must turn back the hands of time and think about the dry savanna where only stunted acacia stands, their spiky hands thrown up in surrender against the harsh sun. That was McDonald’s inheritance of loss, the bittersweet consolation for the coveted peerage from the Queen of England that had fallen through the bureaucratic cracks between London and its colonial outpost of Mombasa.

So, as was typical of McDonald, he ignored any signs to the contrary and continued dreaming that another future was possible for him and Sally. He saw the virgin territory and trembled with lust. He would conquer nature and assert his control, make something out of it for himself and, in the process, leave his mark on the world. He had been to different territories in the colony where locals had adopted names of missionaries who had ventured there, and remembering them, he felt a clog in his throat, for long after those men of God were gone, memories of their life would linger. There was Kabarnet, named for Reverend Barnett who had pitched a tent in Nandiland. Or one could point at Kirigiti in Kikuyuland, where the Brits’ love for cricket had earned them immortality in the name of the place.

Above all else, McDonald wanted to please Sally, estranged from him since the incident in South Africa, and for the entire duration of the railway construction. He would prove he had been worthy of her love.

So, soon after his discharge was confirmed, and London reaffirmed that the coveted title for his service to the empire had been erroneously replaced with a deed to a piece of earth he neither desired nor needed, McDonald wrote to Sally. His first letter went unanswered. And the second, and the third, and the fourth. She answered his seventh letter, clarifying that she had been prompted to respond not by his persistence, which she remarked was a sign of foolishness—a wise man has many ways of sending a message, she said—but because the last letter had arrived on her birthday. Any meanness of spirit wasn’t permissible on her special day.

Sally said she would think about the visit, which to him meant his request had been considered favorably. He knew Sally was not the thinking type; she acted on impulse, so any claim that she was thinking things through was, in fact, an affirmation that she had already made her decision. Her final letter with confirmation of dates and itinerary arrived six months later. She would be visiting in another six months. She then added:

I’m curious to how you use your fork and knife these days. I recall you had trouble drawing butter from the jar and putting it on the side plate. You liked buttering your bread direct from the jar, which ticked me off without fail. I suspect you must be eating butter directly from the jar since, in your military wisdom, bread and butter eventually meet in the stomach.

Sally wanted to find out if he had gone native, McDonald thought happily; he would prove to her he had only grown more sophisticated. He would demonstrate to her that he was as good as any Englishman; in fact, he was as good as her father, whose country home in Derbyshire he replicated in the design of the Nakuru house. He worked his men like donkeys, most of them artisans he had diverted from the team detailed to maintain the new railway, and so worked at no cost to him. None of them knew their old boss had been retired.

The concrete blocks were sourced from other faraway colonies like the Congo and Nyasaland and hauled uphill by African handymen. The blocks were used as cornerstones that were a slightly different shade from the rest of the wall, and were placed at calculated intervals to evoke the pattern of a staircase. Once again, McDonald maintained the division of labor he applied on the railway construction. African laborers teamed up with an Indian artisan. A white architect named Johnson—whom the African workers called Ma-Johnny—provided general oversight.

Workers sang songs to urge others; they cracked jokes to deflect attention from their backbreaking toil. “Hey, man, a bird is going to perch on your head thinking it’s a tree!” one worker would tease another who was considered lazy.

“Maybe he will help build its nest,” another would join in.

During the rail construction, McDonald had discouraged joking among the workers because he believed those busy using their tongues were misdirecting their energies. But he had become more tolerant during the construction of the house—not that the workers necessarily knew this. To be on the safe side, the workers continued to fall silent at his approach.

When workers fell short of their projected goals, McDonald organized overnight shifts. That’s when the glowworms in the marshes were replaced by lightbulbs and locals who had never experienced electricity were drawn to the lights, just like the moths that buzzed around the bulbs, singeing their wings and doing their death dance before paving the way for more suicidal insects. The locals stood and marveled: Muthungu ni hatari, they said, admiring the discoveries the white man had brought to their village. In that spirit, few spoke about the builders who had been killed or maimed in their labors, or devoured by wild animals at night while working. And those who did speak of these casualties concluded with philosophical zest: an abattoir is never without blood.

The house was completed in ten months, sixty days ahead of the projected deadline. McDonald devoted the last months to supervising the gardens as well as the jacaranda trees that he ordered planted along the road that led from the train station to his house so that Sally would be garlanded by purple blooms when she set foot upon the land in 1902. The idea of the blooms came straight from the Bible, or McDonald’s vague recollections from Reverend Turnbull’s sermons about Jesus’s dramatic entry into Jerusalem garlanded by palm fronds from enthused followers.

He thought the jacaranda reflected Sally’s beauty, and the trees were in full bloom when a horde of servants in a horse-drawn chariot was dispatched to fetch Sally from the Nakuru train station, only a few miles away. Some of the trees had shed their leaves, turning the black earth into a purple carpet. McDonald stayed home to receive guests who had been invited for the banquet. A band had been invited all the way from Nairobi to perform, as was the chef and the kitchen staff. It was the same chef who had cooked for the first colonial governor in 1901, and would be detailed to cook for the Queen of England when she visited the colony years later. The freshest English pastries had been delivered on the weekly flight that brought in the mail from Nairobi. The smells wafting, the piped music floating on the air, combined with the modulated laughter from guests who had already arrived, provided a sense of joy for those assembled.

At the dining hall, a matron hired from Nairobi had drawn up a list to ensure the right sort of people sat together. Engineers from the railway department, for instance, would sit with hoteliers and civil servants and businesspeople. The idea was to mix all manner of professions to spice up conversations and put different perspectives to debate.

The lilting music from the cellos and wind instruments was exactly right for the light refreshments being passed around. Reverend Turnbull was seated between an anthropologist named Jessie Purdey on field research from the University of London and a retired district commissioner named Henry James. On the other side of the table was a youngish woman with a sunburned face and freckled nose. Her name was Rosemary Turner and she giggled when Reverend Turnbull introduced himself.

“How can a reverend have such a cocky name?” she drawled. She proceeded to spend the rest of the evening stepping on his shoes and pinching his thigh.

What followed remains a topic of heated debate to this day, without a discernible conclusion or concurrence. With the passage of time, previous rumors would acquire more sinister pegs so that Sally, the malkia, became a legend in her own right. But as local people like to say, where there is smoke, there is fire, and the smoke and smog that clouded Sally’s visit had one consistent thread: she made a brief appearance at the party incognito before exiting fast.

There were claims that she sneaked into the party disguised as a beggar to test McDonald’s kindness, and was promptly chased away by the guards. Yet others claimed that when she arrived on the coast, she had visited a medicine man who gave her special herbs and charms that allowed her to transform herself into a cat, to spy on McDonald’s house and his friends before making her quiet exit, never to be seen again. Another rumor that became firmly entrenched in the Nakuru lore was that Sally arrived without any disguise, took one look at the edifice built in her honor, sneered that it resembled a chicken coop, and spat on the ground to show her disgust before walking away, with McDonald in tow, pleading with her to return to him.

So, to lay the debate to rest, here’s the true version of the events of that day: Sally arrived on the train from Mombasa as scheduled and saw the African servants waiting to receive her. They were holding a placard carrying her name. On it was McDonald’s looped scrawling, identifiable from a mile away. Sally waved at the servants, who scrambled for her luggage and packed it in the carriage. As she hoisted a leg up to board the carriage, that aforementioned cheeky whirlwind did its thing and she was left with her skirt briefly covering her face, mildly embarrassed but otherwise in good cheer, even after the servants abandoned their mission. The horse trotted back home without the distinguished guest but bearing her luggage.

McDonald panicked when he saw the horse return with the two suitcases but without the servants or Sally. He responded with mathematical precision: adding all the facts together, he concluded that the servants and Sally were together, as memories of that morning in South Africa flooded back to him. He paused to think further; there were four servants involved. Even with Sally’s preponderance for bedding her servants, she certainly couldn’t manage all of them at once. There was a wave of relief as he realized it was implausible that they were all together. Yet, the horse’s presence with Sally’s luggage showed she had met his servants. So where were they?

As guests continued to stream in and greet old friends, McDonald quickly organized a search party that tracked down all the servants within the hour. Recalling the abduction of some British engineers four years earlier, McDonald was fearful this could develop into another crisis, so he had ordered the servants to be restrained from escaping, using any means necessary—a coded message for what military men called “appropriate force.” From the servants’ cuts, bruises, and bleeding noses, it was evident that those unleashed on them had applied McDonald’s instructions to the letter. Some inebriated guests joined in the flogging as the four men were delivered to McDonald’s house, arms tied behind their backs and roped together so that if one fell, the others followed suit.

It was during this commotion that Sally stole into the compound, having spent the hour picking flowers while following the horse’s trail. She was actually tickled by the whole episode and thought no further about what may have prompted the servants’ flight. She instantly recognized the man who had been holding her placard. He had a wound under his left eye, and he looked pleadingly at her when she arrived. Sally thought of her naked truth, as she called her windy exposure. It was nature’s way of reminding her of her vulnerability, much the same way a hurricane sweeps onto the shores to return all the waste the humans have deposited in the sea for ages. Or a shoe that filters to the surface long after its owner is drowned. Sally thought she was being reminded of her own ordinariness, her near-nakedness reminding her of a birth into this new world, bearing nothing but her skin.

Sally did not speak a word nor venture beyond the porch; she simply turned around and went back the way she had come, a shudder in her chest, a quiver on the lip, as memories of her college days flooded in. She had enrolled at the University of London to study history and, out of curiosity, took a minor in African history. A huge chunk of the study was dedicated to the transatlantic slave trade. Sally had nightmares reading about the inhumane treatment the slaves were subjected to on those trips. But what broke her heart was encountering her great-grandfather in the list of merchants who transported African slaves through Bristol to the new lands. How could a man related to her have been party to such injustice?

Sally staged a solo protest against slavery by making amends to the next black man she encountered—a bearded student she had seen in the library a few times. He was from Ghana, shy, somewhat awkward. She invited him for a drink, gave her room number, and fled before he found his voice. He arrived as agreed and knocked timidly. Before the man could say Asantehene, Sally smothered him with kisses and undressed him, and it could have been misconstrued as rape had the young man not relaxed and grinned.

Sally’s one-woman protest did not end there; her tryst with the South African gardener was prompted by the same instinct: an unspoken guilt over past mistreatment of blacks through slavery and her patriarch’s complicity in it. After reading Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness days after its publication in 1899, her estrangement from white privilege was complete. How she rationalized that it was right or moral to enjoy the trappings of comfort acquired through slave labor—the backbone of her family wealth—nobody knows. It may well have been what prompts a soldier to lay down his life for country, even when the cause that takes him to the front line is fraudulent; or for those inclined toward the divine scriptures, it is the same principle that leads a righteous man to lay down his life for sinners. Sally’s salacious behavior made her neither profligate nor righteous—her actions may have been an affront to the laws of the land but one could hardly consider them divine. Yet, it was difficult to divorce the simple privilege that her past afforded her, which freed her from the rigors of earning a living to fornicate at will. That fact of her life had been secured decades earlier, so her communion with black males, whether students in London or gardeners in South Africa, could only be seen as returning a favor of sorts—thanking the black forebears who had made possible her comfortable future.

So when Sally caught a glimpse of McDonald’s brutalized servants, it brought back that resentment. She walked away in silence.

She may not have spoken a word, but many words were spoken about her, especially after the assembled guests were told by a deflated and defeated McDonald that the guest of honor was unlikely to grace the celebrations due to some unexpected developments. He had been unable to extract any information from the servants, beyond the wind mishap and their flight from the station. But guests who had had a little too much to drink shouted that McDonald was lying because some had reported sighting a mysterious guest arrive and depart almost immediately. And since no one in the colony had met her previously, they all remarked on her skin, which was whiter than anyone they’d seen, her springy and dignified gait, as well as her manner of clothing, which was heavier than the Nakuru weather required.

It was Sally’s letter from England a month later that finally broke McDonald’s heart, resulting in a depression during which he locked himself up and mourned his loss. By then, McDonald had confirmed that Sally had arrived on the coast as scheduled and departed soon after, but he had no way of verifying whether or not she had visited his house:

I am distraught to write this letter, the last to you from me. Your cruelty toward me and fellow men, which I have borne and witnessed over the years, is the ground on which I’m filing for divorce. Yours is the Heart of Darkness.

Sally

Had locals been privy to this missive, they would have concluded that Sally was a witch, able to cast a spell and unleash a spirit. For the house that McDonald built soon turned into a veritable heart of darkness, with the windows shuttered for years and signs warning women to keep off the premises posted all over the property. Only male servants were allowed in the compound. They, too, were ordered to wear black uniforms because their master was mourning, although he did not specify his loss. Some overzealous workers chose to wear sackcloth as a mark of their loyalty, and those who learned about the secret code on the posters also abstained from touching their wives in solidarity with their master.

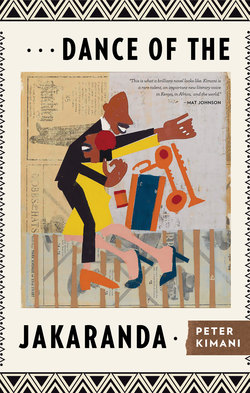

And when the doors and the windows to the house were finally opened, the villagers were surprised to see cows rearing their big heads in the doorway. That’s when the edifice was converted into a farmhouse that later gave way to the segregated social establishment, which further gave way to the multicultural outfit named the Jakaranda, the letter k for Kenya replacing the c in the jacaranda that McDonald said sounded “colonial.”

Now, on the cusp of the new republic and a new dawn for its multicolored citizens, the Jakaranda was about to acquire a new identity, yet again.