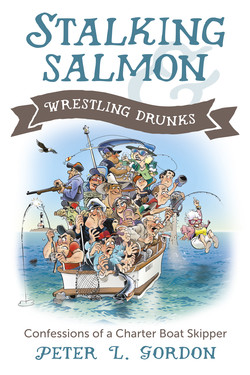

Читать книгу Stalking Salmon & Wrestling Drunks - Peter L. Gordon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

chapter 1 Visitors from Texas

Оглавление“Well, we have a tall Texan.”

A hundred yards from our slip, by the marina office, I could see our party making its way down the rattling metal ramp to the floating dock. Between them they were carrying enough bags and baskets for a ten-day fishing trip.

“So what’s your guess?” I asked Sten.

This was a game Sten and I played before each charter. Simply by the appearance of our guests, we would guess at how the charter was going to turn out. I counted the number in the party—I knew there were supposed to be five.

“They’re all there,” I said. “So what do you think?”

We knew from the booking that a local resident was hosting visitors from Texas whom he wanted to take salmon fishing. We also knew they wanted to troll as opposed to drift fish. In those days, trolling—fishing with the vessel in motion—entailed the use of large flashers, hand-cranked downriggers,heavy rods with heavy line. By far my favourite choice was drift fishing—allowing the vessel to gently drift with the current with the engine off.

Sten was peering at the advancing group through my Zeiss binoculars. “They’re going to be a pain,” he predicted. “I’ll take the helm the whole trip. You handle them.” Usually the man at the helm had little to do with the guests. His job was to find the fish, keep us clear of kelp and keep us off the rocks.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “I’m not hearing that little alarm bell in my head that I sometimes get with certain idiots. So go ahead—take the helm. I think this is going to be a blast.”

I said this partly to tease him but also to initiate the bet. We invariably had a bet on what the people were going to be like. This time I was certain I was right, but the bet was on as usual.

It was a lovely, clear day with no wind. We would reach the high slack tide—slack tides are prime fishing periods—in about an hour and a half. If the people were pleasant and the fishing was good, except for the fact that I’d rather be drift fishing, the trip would be perfect.

Sten, my assistant deckhand, was a retired commercial fisherman in his mid-thirties when he applied for a job to work on my boat. From the age of fourteen he had worked as a deckhand on commercial fishing boats during his summer vacations. He had fished the waters all the way to the northern tip of Vancouver Island and beyond. He knew more about fishing than almost anyone in my circle of friends. Like me, he preferred to fish for salmon with light tackle. Trolling using forty-pound test line and rods that resembled broom handles gave us much less joy, but sometimes we had to pull out the trolling gear and put it to use because the customers requested it.

Sten had retired from commercial fishing after being caught once too often by a fierce storm off the northwest coast of Vancouver Island. It was a killer storm lasting five days; much of that time Sten was lashed into his bunk, severely seasick. After the storm subsided, half the deck gear was torn away and every pane of glass in the wheelhouse was shattered. The skipper, who was also Sten’s uncle, refitted his boat then put it up for sale along with its licence. That was when Sten applied for work with me.

In addition to his quiet good nature and enthusiasm, Sten was a magical fisherman who never lost his joy of fishing and loved to see other people catch fish. Big fish—he loved it when they caught big fish. A fish, to Sten, was always a salmon. Even a 150-pound halibut was simply a slab, not a fish. Moreover, he didn’t drink or use drugs, his language was sanitized and he was always on time—and he could cook. His reaction to our advancing party from Texas was out of character for him, so much so that I briefly doubted my intuition. I took the binoculars from Sten’s hands and watched the group as they made the long trek down the dock to our slip at the farthest point from the marina office.

No, I thought as I watched them approach, they seem all right to me. But I would let Sten have his way. He could handle the helm for the entire trip while I dealt with the guests and the gear.

This was my ninth year operating the company. Several things had changed over the years, including the introduction of a saltwater fishing licence along with serious catch quotas. In my first year of running the operation, saltwater licences did not exist and almost any size of salmon could be kept. The old-timers use to fill their freezers with coho grilse, immature salmon that had to measure only six inches to be allowed to be kept. Those they did not cook during the year would be ploughed into their compost heaps before the cycle would start all over again. Nearly a decade later, that practice had largely come to an end. There was also a move away from the food-catching mentality to a sport-fishing mentality. This new approach had become so well entrenched by my ninth year that many of the sport fishermen were releasing their undamaged catch for the purpose of conservation. We applauded these changes.

By my third year of operation, I had shifted our charters from a strict focus on catching salmon to a salmon-fishing trip with overtones of a nature tour. During the off-season I encouraged Sten to read and study various nature books so he could identify and learn about the birds in our region, their habitats and their life cycles. Other books taught him about the wildlife below our keel and the struggle for life that played out with each changing tide. He was clever and a fast learner, so it wasn’t long before he was giving lectures at the stern of the boat on the life cycle of Steller sea lions or some other form of wildlife visible from our deck. Occasionally—not often—he would mix up his facts. He once described the life cycle of a puffin when instead he meant a cormorant—two very different birds. However, none of our guests appeared to notice these mistakes, and I was never sure whether Sten was doing it on purpose. To be on the safe side, I would make a point of correcting him after the charter, but only when we were alone, sitting in the galley having a cup of coffee and discussing the events of the day.

In this relaxed atmosphere, I would also make notes in the ship’s log concerning the fishing conditions, the type and number of salmon we caught, the lures we used and the depth at which we caught our fish. Memorable charters when the people, the weather and the fishing were perfect required additional space in the log. It is these recorded memories that have served as the basis for this narrative.

Sten turned on the blower to remove potentially explosive gases from the bilge and then he fired up the engine. The VHF radio clicked on, followed by the CB, which immediately began to chatter like a parrot on an illegal stimulant. Sten turned it down and adjusted the revs on the engine. This was all done just as our party arrived alongside and prepared to board.

“Permission to come aboard, Skipper?” the local fellow asked. I liked this little ceremony.

“Please make yourselves at home. The Kalua welcomes you,” I said. Good start, I thought as I glanced at Sten at the helm.

My vessel was called MV Kalua, a name and spelling I inherited and at first wanted to change. But the very idea was considered such bad luck that when I tried to change it, no one would answer my calls on the CB. So that plan quickly sunk like a stone in Victoria Harbour.

The first person to come aboard was the local man, who introduced himself as Jake. This was perplexing, since during the entire trip no one else called him Jake except me, and it remains a mystery to this day. He clamped me by the shoulders and whispered in my ear that his guests were special friends from Texas and he really wanted them to catch a salmon. I told him we would do our best.

Next the tall Texan, Chuck, came on board. Reaching over the railing, he helped a diminutive blond woman onto the deck, who turned out to be his wife. Scarcely more than five feet tall, she was wearing skin-tight, neon blue designer jeans with red embroidery on the back pockets, matching deck shoes and a light blue blouse with three-quarter-length sleeves. A light scent hung about her that reminded me of lavender.

“Are you wearing hand cream?” I asked. Most fishermen agree that a lure should not carry human or chemical smells. Women often came on our charters wearing hand cream, which tainted the lures with the odour of the cream. The hands of smokers had the same effect, so we would try to convince them to wash their hands as well.

“Yes,” she said. “Do you like it?”

I looked at her closely for the first time and realized she was a stunningly beautiful woman. “Remember to wash your hands before you handle the gear.”

She looked up at her husband with slight embarrassment as though expecting a reprimand. “Don’t say it!”

“Honey, it ain’t nothing.” He flashed her a generous smile. They had obviously discussed the use of hand cream before leaving home.

The rest of the party clambered on board, struggling with hampers, bags and baskets. I helped them down the companionway and into the forward cabin, where they could stow their gear and make themselves at home while we cast off.

With Sten at the helm, I did the honours. I unfastened the spring lines, which prevent fore and aft surging, then the bowline. There was no wind so I gave the bow a push away from the dock while Sten slipped the engine into reverse and spun the helm a half turn. The Kalua slowly moved in reverse and strained against the stern line I had wrapped around a bollard on the dock. As the bow swung around, I fed out the line until the vessel had spun a full 180 degrees and was facing the channel that would take us into the bay. With Sten’s eyes on me, I nodded at him when the boat was in position, unwrapped the rest of the stern line from the bollard and stepped onto the stern deck with the line in my hand. We smiled at each other. The slack wind had helped us to execute a flawless cast-off, but no one would notice except us.

During the next half hour I made sure everyone had their licences and that they were properly completed. I also went through the routine of demonstrating how to flush the toilet in the head—the W.C. Although I’d made many upgrades to the boat, the toilet was still operated manually with instructions attached to the back of the head door. At least twice a week one of our guests would emerge from the head with a bewildered look and ask for help with flushing. It was simple: use the toilet, lower the lid, put your right foot on the only pedal available and work the lever back and forth to pump the bowl clean. Easy, but more complicated than pushing a handle, and baffling to many members of the general public.

While I checked fishing licences, poured cups of coffee and pulled hot Danishes from the oven, Sten took us at planing speed to our first fishing spot. As we approached, he throttled the engine back slowly, and the boat settled from its plane into the water. Sten turned on the paper sounder—also known as a depth sounder or echo sounder—and I heard the click, click, click of the stylus scoring the thermal paper. In five minutes Sten would call out that we were ready to begin fishing. Before going to the stern deck to set up the fishing gear, I’d have a quick look at the paper sounder, which would show us the baitfish; this in turn would give me an idea of the depth at which to start fishing. Sounders were originally developed to show depth; revealing the presence of fish turned out to be a bonus. The downriggers were already in place and the lead weights ready to be mounted onto their stainless steel cables.

The routine of setting out the fishing gear always attracted a crowd on our spacious stern deck. First I set up the downriggers, then the rods with the lures at the end of their lines. On this day I wanted a slow roll to our bait, meaning the lure imitates a wounded spiralling herring. Sten throttled back as I lowered the gear to fishing depth. And just like that, we were in business.

With everything set and in place, I turned back to the group of fishermen and explained that when a salmon took the bait, the bell on the arm of the downrigger would ring and the fish’s strike would release the line from the downrigger. I would pick up the rod and crank in the slack line until I felt contact with the salmon on the end, then hand the rod to the first designated fisherman.

“Have you decided who’s going to take the first strike?” The group of eyes was staring at me intently, but I directed my question to Jake.

“I think that should be Chuck,” he said tapping the tall Texan on the arm. Not a surprising choice, I thought.

“Aw, come on, Al, you take the first strike. You’re local—show us how to lose a fish.”

Al? Jake? Okay, whatever. I laughed along with everyone else. “Show them how it’s done, Jake,” I said. “You’re not going to let some Texas greenhorn jerk your chain, are you?”

As I spoke Sten’s hand shot up; simultaneously the portside downrigger bell gave a single ring. Out of habit I snatched the rod out of its holder, cranking furiously on the handle until I felt the heavy weight of the fish at the other end. Sten had put the engine into neutral and come down to help me. I held the rod tip up and tightened the drag slightly. I could feel the fish thrashing at the end of the line but not running.

Sten raised both downriggers and unclipped the weights. “Any size?” he asked.

“Under twenty pounds, over fifteen.”

“You going to hand it off?”

“Uh-huh.” I knew what he meant with his question. We would have a better chance of landing the fish if I played it. Returning to port with a fish on ice is important for the overall experience. Still, I knew Jake and Chuck would be eager. I called over my shoulder, “So who’s it going to be?”

Jake was standing beside me, trying to say something. I grabbed his right arm and placed the rod firmly into his grip. “You play it,” I said. “It’s a good fish.”

As I handed him the rod, the fish took its first run. When a fish “sounds,” it is heading for the bottom of the ocean. This salmon didn’t sound—it didn’t head for deep water—but screamed to the surface in a headlong rush for the horizon, trailing line behind it.

“How much line do you have on this thing?” Jake asked under his breath. I could tell his adrenalin was pumping by the quiver in his voice and his jerky movements.

“Enough. Keep your rod tip up and keep pressure on the fish.”

His rod tip came up twenty degrees and he stopped reeling as the fish peeled out line, pulling against the drag on the reel.

“Watch out,” I said. “It’s going to stop and thrash, so keep pressure on it.” Before Jake could follow my instructions, the salmon sounded then came streaming back at the boat.

“Reel!” I shouted. “Come on, reel faster or it’ll throw the hook. If that happens, I’ll throw you overboard.” My joke didn’t go over too well. Jake was quivering and barely able to turn the reel handle in a circle. We called these fishermen square shooters because they turned the handle in a jerky manner instead of a smooth circular movement.

“Faster,” I said in his ear. “Come on, catch up to him.”

He was reeling frantically now, picking up the loose line. At the moment he caught up to the fish, his rod doubled over and was nearly yanked out of his hands. The entire length of the rod was jerked up and down forcefully as the salmon thrashed underwater in a desperate battle to save its life. The reel again began to creak out some line.

“Drop your rod tip and reel as you do, pull up slowly, then drop your rod tip and repeat the action. It’s a pumping action,” I told him.

For the next fifteen minutes, the salmon fought for its life while Jake struggled to bring it alongside. Each time the fish saw the boat it screamed out line, which had to be retrieved with some effort. Each time it took a run it was shorter; exhaustion was setting in and no amount of courageous instinct could match the sophisticated reel and line we were using.

The smooth, stainless steel ball bearings in the reel rotated flawlessly as the monofilament line stretched instead of snapping and the rod acted as a shock absorber, reducing the thrashing of the salmon to manageable bounces at the end of the rod. A brief but courageous final run and the salmon turned on its side. I netted it and swung it onto the deck. It was gasping, its gill flaps working to extract oxygen from the air.

The boat erupted in cheers and Chuck gave a loud “Yee-ha!” Looking at the salmon, I knew that even if I could persuade the fishermen to return this beautiful, rainbow-silver fish to the ocean, it would die. The effort of the struggle and the shock of being caught were too much.

I reached for the Priest and banged the fish on the head. “Go home now,” I said softly—a ritual that was an act of respect for the life we had just taken. A “priest” is a small club used for ending a fish’s life. They are sold in stores but I made mine. The name comes from the idea of administering last rites to the fish, or perhaps from stories of priests beating the tar out of young boys who were the unfortunate targets of their disciplinary measures. I still have the Priest from my charter boat.

Jake was quivering.

I shook his hand, saying, “You played that well.”

“No,” he said. “I couldn’t have done it without you.”

“Don’t be silly. I just cussed in your ear a bit.”

“Do you think it will go twenty pounds? It has to be at least twenty! I’ve never caught a twenty—fourteen is my biggest.”

“This time next year it’ll be at least thirty,” I said, knowing how fishing tales became taller with the passage of time. “But right now—before time, stories and too much fresh air put weight on it—I would guess it’s seventeen.” I looked up at Sten, who was at the helm studying the paper sounder. “What do you say, Sten? Seventeen?”

“Eighteen at least—right now.” He smiled.

I pulled out my trusty scales and read off the weight: “Eighteen!”

Again there was a cheer from the crowd on the boat. Everyone shook hands while I picked the salmon out of the green mesh of the landing net and placed it in the cleaning tray at the stern of the boat.

“How do you want it?” I called out. “Ears on or off?” No one answered. They were congratulating one another and opening chilled cans of beer. We were still drifting in neutral; Sten was still at the helm examining the paper sounder.

Leaving the fish in the tray, I made my way through the group of people, up the four steps to the helm and over to the sounder to look at the readings.

“Nice haystack,” I said, referring to the haystack shape the stylus scored on the sounder paper. It represented the outline of a school of herring. At the base of the haystack were white areas where the herring had been chased by feeding fish or birds. Probably salmon, I thought. “What do you think, Sten?”

“I think we should do an about-face and make the same run.”

I smiled. “Let’s do it. But give me time to clean the fish. Nice fish,” I added.

“They’re all nice,” he said. “Especially the big ones. I’ll cruise us back at three or four knots.”

“Fine. Let me know if we pick up any top hats.” A top hat was our term for a fish that showed on the paper sounder as a large circumflex accent. It indicated a large salmon. Since we both spoke French, which uses that accent frequently, it was an obvious way of describing the mark on the paper. When I returned to the cleaning tray, both Chuck and Jake were holding cans of beer and staring at the salmon in the tray. “Ears on or ears off?” I asked Jake.

“Ears on,” he said with a smile. “They look prettier that way.” “Ears on” means the fish is eviscerated, its gills removed as well as any lice clinging to the vent area. The head and pectoral fins are left on, which makes the fish look as though it has been mounted.

Chuck was watching with a wry expression. “Damn,” he said. “Back in Texas we use fish that size for bait.”

“Damn,” I echoed back at him. “You don’t have any salmon in Texas.”

We all laughed. Chuck and Jake smiled at each other and had a sip of beer. It was all good-natured. Chuck was playing on his image as a Texan, and the fact that he was at least six foot six and wore a grubby and mashed-up ten-gallon hat added to the stereotype.

“Seriously,” Chuck said, “are you telling me this is what you guys call a fish?”

There was a crinkling around his eyes and he winked at Jake so I knew the remarks were meant for me. I also knew I was in for a protracted leg pulling. It was all right—it was their charter and he was a guest. “Maybe the next one will look like a fish to you,” I said.

“It’ll have to be able to swallow this one,” he retorted.

This is turning into lots of fun, I thought.

I cleaned the fish using our stainless steel knife, which had a large yellow handle and a spoon attached to it with electrical tape. I unzipped the fish from vent to chin before cutting out the vent, leaving it attached to the rest of the intestines. When I separated the intestines from the salmon with a neat cut to the throat, out came a handful of guts in one clean package. I cut out the gills followed by the kidney, which was scooped from the base of the spine using the spoon attached to the knife handle. Next, to see what it had been eating, I cut open the stomach, which was packed with herring the size of those we were using at the end of our flasher. I threw the handful of guts over the stern railing to a small flock of seagulls that had started to follow us as soon as the fish was in the cleaning tray.

Good start, I thought. The first one’s always the hardest to catch.

By the time I had the fish ready to stow in the chest with crushed ice, we had cruised quietly back to our starting point and turned into the flooding tide. I washed my hands in a bucket of salt water, dried them and prepared to reset the lines. One of Jake’s friends, a foggy-looking fellow who introduced himself as Mason and was wearing clothes that were obviously too small for him, asked if he could help set the gear.

“Have you ever set lines using a downrigger?” I asked.

When he said he had not, I suggested he stand back and watch how it was done. He looked so disappointed that I changed my mind and talked him through the procedure, which added an extra ten minutes to the line set. I let him do everything except attach the line to the downrigger, a procedure that is an acquired skill. Too much pressure and the fish is unable to disengage the line from the downrigger cable; too little pressure and it will pop free with the slightest change of current.

After we’d set the downriggers, I asked, “Who takes the next strike?”

A general conversation broke out, everyone suggesting someone else when each person really wanted to be next.

This wasn’t getting us anywhere so I stepped in. “The local resident is going home with a salmon, so now we have to send our guests away with a one. Chuck, that means you or your missus. Who is it to be?”

“Blue Eyes,” Chuck said to his wife, “I’d like you to be next.”

Sometimes we didn’t learn guests’ names until we were setting lines later in the charter. I wasn’t about to call her Blue Eyes, and she avoided any awkwardness by saying, “Please call me Jeannie. Mrs. Jeanne Arnold, the recent Mrs. Jeanne Arnold.” Her speech was very Southern, softer than Chuck’s but just as nasal.

“Congratulations,” I said, a bit surprised. “Does this mean you two are newlyweds on your honeymoon?”

Chuck stepped from behind her and draped his arm over her shoulder. She took his hand and held it in both of hers.

She’s so short and he’s so tall, I thought. They were radiating love. Their pleasure splashed onto everyone in the group, and I found myself grinning along with everyone else.

“We’ve been married just four days,” Chuck said. They continued beaming at each other in such a happy, transparent manner that it was infectious. I reached out to Chuck and shook his oversized hand. I could feel it was a hand that had done some practical labour, and I wondered if he had a ranch and rode horses. Instead of shaking Jeannie’s hand I gave her a hug, which brought a round of applause from everyone. It had all been so spontaneous I felt a bit silly.

“So are you going to be next, Jeannie?”

She looked up at Chuck with real pleading in her eyes. “I don’t think I can, honey,” she said, “I mean, Albert had a tough time with his fish and it wasn’t even so big. I don’t think I could hold onto the rod.” She looked anxious and Chuck seemed unsure of what to do.

I didn’t want to get into a discussion about an eighteen-pound salmon being small. Instead I said, “How about if we run the same routine we did with the last one? I’ll pick the rod out of the holder and strike the fish. If I think it’s over ten pounds, I’ll hand it to Chuck, and if I think it’s under ten, I’ll hand it to Jeannie. Does that sound okay?”

Some mumbling and murmuring ensued as they all looked at one another and tried to decide what to say. Finally, Jake agreed with a nod of his head. “Okay, let’s do it that way.”

I glanced up at Sten but he was staring ahead, so I made my way up the companionway to the helm and had a look at the paper sounder. There was lots of feed and we were on the edge of a large haystack that started at around two fathoms and went down to six. Six feet to a fathom meant thirty-six feet to the bottom of the haystack. Salmon usually lurk just below the feed.

“I’m going to drop the starboard line down to sixty feet,” I said.

“Good idea.” He kept his eyes focused ahead.

“Anything up front?”

“Kelp.”

“Much?”

“Enough.”

“Let me know if it’s going to be a problem.”

“No problem yet.”

I went to the stern of the boat and checked the tension on the reels. It is important to have the drag set tight enough to set the hook when the fish strikes, but not so tight that the fish cannot run. A light breeze was blowing and I could smell the herring and the kelp in the air. When the ocean has an abundance of feed, the air around you starts to smell of fish oil. While it is not a strong smell, there’s nothing better to make a fisherman feel optimistic. Kelp, with its smell of iodine, is always welcome.

Sten was moving the boat forward slowly on a zigzag course, partly to avoid the islands of kelp floating toward us on the flood tide, and partly to alter the movement of the bait and flashers at the end of the downriggers. When kelp is around it’s important to check your lines frequently to be sure you are not trailing some of it from your lure.

For the next while I worked the lines. The whirl of the downriggers became commonplace to the guests, who had spread throughout the boat and no longer stood around as I brought up the lines to inspect the bait.

As noon approached, Jake and his friends busied themselves unpacking their hampers of food and setting it out on the table in the galley. The smell of the food imposed itself on the fresh sea air, so I kept my distance and stayed as close to the stern as I could. Something about some picnic foods and the aroma of damp, limp sandwiches can turn my stomach, especially if tomatoes are involved. Sten, on the other hand, kept peering expectantly down the companionway into the galley like a wolf in search of a carcass.

The sounder was still showing dense feed so I altered the depth of the lines a few times to see whether that would draw a strike. It didn’t. I decided to change the bait from the fresh herring we were using to a Tomic plug—but only on the portside downrigger. I had a favourite beaten-up plug that often produced a fish when little else was working. I brought up the downrigger and swung the weight into the cleaning trough before unsnapping the flasher with the bait attached to it, then replaced it with my plug using an eighteen-inch leader. After lowering the weight back into the water, I watched the action of the plug for a few minutes, trying to understand why this plug worked so well. I had no idea—it seemed like all the other plugs I had in my tackle drawer. I put the line down to forty-eight feet. I wanted these people to go home with memories of catching a slug—a really big fish, the kind you might lie about—off the West Coast of Canada.

We fished through the flood tide and into the slack. The activity was good, with the bell on the downrigger continually ringing and giving everyone a chance to play a fish. By the time the tide began to turn we had five salmon on ice. We had lost as many.

Chuck and Jeannie caught a brace of salmon between them. Sten and I had both been wrong. Despite her delicate, polished appearance and her initial trepidation, Jeannie surprised me by playing her fish with easy skill, which made me realize there was depth to this young bride. She also had a sense of humour. While they didn’t break world records, they had some good fish that had fought with courage. Just before the tide started to run I suggested we pull up all our lines, find a quiet spot and finish our lunch. Everyone agreed, so Sten cruised us to a serene eddy we often used, cut the engine and came down to the galley to plough down some food. I was surprised to see him mingle with the guests since he had been adamant about remaining apart from them, but I kept my thoughts to myself. I’d remind him later that I’d won our bet.

At the stern of the boat I kept an eye on our drift; although we were in a back eddy, the tide was changing and currents could shift abruptly. This is perfect, I thought. There was just a slight breeze, the sky was a crackling blue, the Olympic Range was crystal clear from twenty-two miles away and the rumble of the changing tide was just beginning to build.

And I have a nice bunch of people. These are the good old days.

At the start of the day, I had been concerned Chuck was going to be a loudmouth who ruined the fishing for everyone; instead he’d turned out to be a thoughtful fellow with a fine sense of humour. Of course, he couldn’t let an occasion go by without pulling our legs about how much bigger and better everything was in his home state of Texas. I’d guessed him to be a rancher, but during one of our conversations he told me he owned a string of fast-food franchises—over thirty of them, Jake later told me. I did the math and realized that Chuck was in a financial comfort zone enjoyed by very few. To his credit he had done it all on his own, starting with one franchise he could barely afford to purchase and sleeping and eating in the back room. Here he was, nearly twenty years later, living the good life. How can you complain about one man’s well-earned success?

“What are you thinking, Skipper?” Chuck had come up behind me.

“I was thinking it’s about time we caught you a real Canadian salmon.”

“I don’t think you’ve got any real fish up here. If you ever come down to Texas, give me a call and I’ll take you out to catch some real fish.” There was humour in his voice and laughter in his eyes. He looked around and took a deep breath. “But it sure smells good up here, and it’s sure pretty.”

We stood quietly, soaking in the scenery and feeling the boat gently shift in the current. Without warning, an orca breached twenty feet from the stern of the boat. Behind it, a second orca propelled its glistening black and white body into the air, landing its massive nine-ton hulk on its side and seriously rocking the boat.

Chuck was thrown back, and as he braced himself against the bulkhead, I saw real fear in his eyes. “What the hell is that?” he yelled.

Without hesitating, I shouted back, “Canadian salmon!”