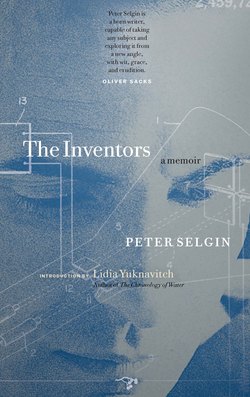

Читать книгу The Inventors - Peter Selgin - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVI.

My Brother, My Prototype

Love is assuming the other’s burden of fate.

HERMANN BROCH

IN TIME YOUR VISITS WITH THE TEACHER AT HIS COTTAGE became routine. From them you would arrive home to find your brother in the bedroom you shared, reading a book or listening to his latest Columbia Records Club purchase – to Phil Ochs, the Beach Boys, Schubert.

George wouldn’t ask where you’d been. He knew. And you wouldn’t say, since it would only have inflamed his jealousy. And you knew that your brother was jealous. You were glad of it. It pleased you to have something your twin didn’t have, something you weren’t forced to share.

One problem with being a twin: you had to share everything. Your birthday, your bedroom, your books, your toys, your looks, your friends, the love and affection of your parents (who treated you, annoyingly, as equals). While others were free to shape their own distinct destinies, as a twin yours was cut out for you in the shape of a sibling.

On the windowsill in her corner room Nonnie kept a miniature version of the Capitoline Wolf, the bronze Etruscan sculpture of a she-wolf suckling the infant twins Romulus and Remus, mythological founders of Rome. With you or your brother in her room she’d point to them one at a time and say, Questo e Giorgio, e quello li Pierino.

* * *

YOUR MOTHER HADN’T EXPECTED TWINS. SHE ONLY found out after you were born. When the gynecologist put his stethoscope to your mother’s chest, he heard what he assumed was one heartbeat, but was really two hearts beating in unison.

Having no names prepared for two children, while our mother recovered from the anesthesia they’d given her for the cesarean section the hospital authorities named you Selgin Boys A and B. You were Boy B.

And though no tests were ever performed to determine zygosity, your mother always insisted that you weren’t identical, that your bodies were formed from separately fertilized eggs. Still you shared the same rare blood type (A-), and until you were well into your teens most people couldn’t tell you apart.

You also fought. Some twins bond, meeting life’s challenges in joyful tandem, like the tennis playing twins in the old Doublemint chewing gum commercials. Not you and George. You both hated being lumped together, bound in a perpetual three-legged race with this other person who happened to share your looks and last name. As far as both of you were concerned, being a twin was no bounty. On the contrary, it was a handicap tantamount to being born with a clubfoot.

At times your rivalry felt ageless. It wouldn’t have surprised you to learn that you and your twin brother had kicked, punched, and insulted each other in the womb. Your entry into the oxygenated world only fanned the flames of antipathy, with taunts turning to fists and projectiles and ending, more often than not, in a visit to the emergency room or Dr. Randolph’s office for stitches or butterfly enclosures.

As you grew the fights only got worse, with frequent forays into the public sphere. When you were twelve, at a backyard party at Karen Finklestein’s boxy little house at the end of a cul-de-sac, as the other guests formed a circle and egged you on, you and your brother wrestled each other down a weedy embankment into a shadowy stand of pine trees. When it was over – as the others looked on, laughing – you and your twin emerged basted in blood, tears, and snot, coated with pine needles.

This inspired a recurrent nightmare. In it you found yourself looking up at a circle of faces laughing, pointing, and jeering at you as you lay on the ground, having presumably fought a pitched battle with your twin, only in the dream your twin is nowhere to be seen, the inescapable conclusion being that you’ve just beaten the crap out of yourself. It was like beating up – or being beaten up by – your own reflection.

GEORGE DID EVERYTHING first. He was the first to collect minerals and postage stamps, the first to read books, the first to embrace what became your favorite TV shows, The Wild, Wild West, Diver Dan, Flipper, Sea Hunt, The Aquanauts, any television show featuring water or scuba divers.

The Aquanauts was George’s favorite. Unlike Rick Nelson in Sea Hunt, who used an old-style, double-hosed regulator, the star of The Aquanauts used a modern, single-hose job. From when he was six, your twin dreamed of being one of Jacques Cousteau’s divers on the Calypso. While watching The Aquanauts he’d wear a pair of pretend scuba tanks your mother made from twin empty aerosol cans. With the spray cans attached to his back with a harness George would scuba dive on the living room floor.

He was the first to wear glasses, a novelty forced upon him in second grade by his astigmatism. The glasses gave him a bookish appearance that, though it may not have determined his scholarly future, foretold it. Because of them, the glare of camera bulbs made him squint in photographs, giving him a put-upon aspect that seeped into the rest of his personality and made him the perfect target for your father’s roguishness.

Like all families, occasionally the Selgins dined out. Among your favorite restaurants was the Ho Yuen, the Chinese restaurant in nearby Danbury with a pagoda-style roof and a flashing neon sign of ersatz Chinese letters over its otherwise humble brick facade. The waiters wore white shirts with thin black bowties and showed no emotion while committing orders to memory. Everything on the menu was brown, gooey, and salty. Your father ordered pork fried rice. Your mother liked the fatty sweet spareribs. You favored egg foo young.

George alone was adventurous. He would put on his double-hosed regulator, scuba dive to the deepest, darkest corner of the menu, and point to some item as unpronounceable as it was enigmatic.

What is this? he’d ask your father.

Ah, yes, your father responded enthusiastically. Get that! By all means!

But what is it? George insisted on knowing.

Oh, it’s much too complicated to explain, your father answered. Ah, but it’s very, very good. I promise you!

Your brother always fell for it. The selected dish would arrive, murky and mysterious in reality as in name. Under your father’s solicitous gaze, George would pick up his chopsticks (he alone dared to use them) and eat – tentatively at first, then more enthusiastically, nodding and making sounds of approval, going “mmm, mmm” as the rest of you, knowing what lay in store, looked on.

Only after your twin had cleaned his plate would your father wipe his mouth, put down his napkin, and announce in a stentorian voice: Now I’m going to tell you what was in it. He would proceed to inventory ingredients appalling enough to send George rushing off to the restroom to vomit.

GEORGE’S ADVENTUROUSNESS GOT him into all kinds of trouble. At fourteen, he took a diver certification course at the local YMCA. The diving instructor would throw a regulator into the bottom of the pool, then make students dive for it, put the hose in their mouth, and breathe from it. There was no excuse for not breathing from the hose. One day, unaware that his oxygen tank was empty, the instructor held George’s head under the water and forced him to breath. He nearly suffocated.

George was smarter than you. On his Scholastic Aptitude Test he scored in the high 700s, verbal and math. Your scores were considerably lower. He never studied for exams. He got A’s anyway. Instead of studying, he’d go to the local ice cream parlor for a hot fudge sundae. Better return for the effort, he reasoned.

With few exceptions (the new teacher among them), he found his teachers lazy and incompetent, and suffered fits of boredom in their classrooms that he went to extremes to alleviate. In Mr. Milne’s chemistry class George rigged up a Bunsen burner so when the team working at that lab table turned it on it shot a resplendent fountain of water to the ceiling. In introductory French class, Madame Griswald would leave her students with headsets and tape recorders repeating Nous allons a la gare and other lame French phrases for the duration of the class, which was held on the ground floor. One morning, George took off his headset, opened the window, jumped out, and started walking. He walked a straight line through lawns, parking lots, abandoned hat factory yards, and an apple orchard. He just kept walking. He got two days’ detention.11

Today they’d call it ADHD.

Another of your brother’s teachers, Mrs. Wilcox (Advanced Science) was in his view so incompetent he led a protest against her. He arranged for all of her students to stalk out of her class, but when the moment came George alone walked out. Mrs. Wilcox was so upset she wrote a letter to the Vice Principal:

Since the beginning of the course George has done his best to disrupt the class, talking and throwing papers around and bothering those around him by taking things off their desks. He claims he’s the victim of circumstances, but whenever he has been absent there has been no disturbance.

In the laboratory twice, due to his carelessness, he endangered the safety of others, first by opening a gas jet and setting it on fire and second by almost hitting someone in the eye with a sharp crystal of copper sulfate which he had no reason to be around.

During a meeting held with a group of students to discuss class concerns, George called his classmates hypocrites and told me I was being close-minded. He went on to say that he was being persecuted by the administration.

More recently when we met to discuss a test grade I’d given him George informed me that I was “crazy.” When told to report to your office he said he would take his time and left the room only after several minutes.

It should be noted that George’s behavior has been the subject of numerous complaints made by other students.

The following year, George signed up for an advanced placement course at Sacred Heart University, a community college.22 Having gone twice to the class and found it no less boring than his regular high school classes, he stopped going. Instead he’d drive to nearby Westport in his Barracuda and cruise up and down its streets before stopping at another ice cream parlor there, an old-fashioned one with an antique soda fountain and marble tables. When Mr. Pearlman, the teacher in charge of the program, found out, he told your brother, “You’re in deep doo-doo,” and sent him to Mr. Forster, who told him that to make up the credits he’d have to take a calculus class.

The same community college in Bridgeport from which, according to his obituary notice, the teacher earned his associate’s degree.

If it’s just a matter of credits, your brother reasoned, why can’t I just take another course for three credits?

Against this the Vice Principal had no argument. Your brother went down the hall, signed up for Male Chorus and earned his three credits singing “John Brown’s Body.”

GEORGE WAS THE first to draw caricatures – a skill that, years later, you would parlay into something of a career. He sketched all of his teachers and classmates, including Harvey Keebler, the new kid in town, with his freckles and Dudley Do-Right chin. Harvey had been the one friend George didn’t share with you, until he phoned Harvey one morning and his mother – who sounded a lot like him, but with a much higher voice, like a man impersonating a woman – answered the phone.

This isn’t Harvey, Harvey’s mother said. It’s Mrs. Keebler, his mother.

Come off it, Harvey, said your brother. I know it’s you.

This is not Harvey, the voice at the other end of the line insisted. This is Mrs. Keebler, his mother.

Yeah, right! your brother said. Come off it, Harvey, quit foolin’ around!

This is not Harvey, this is Mrs. Keebler.

And so on.

The more the voice at the other end of the line insisted that he/she was Mrs. Keebler, the more convinced your brother became that his best friend was pulling his leg.

Finally your brother blurted, Well, if you’re going to be that way about it, tell Mrs. Keebler to go fuck herself!

Only after the line went dead did he realize his terrible blunder. From then on he was forbidden to have anything to do with Harvey Keebler.

GEORGE WAS THE first to get a part-time job (First National, dairy section), the first to get his driver’s license, the first to buy a used car (’65 Plymouth Barracuda, slant six, make-out window, bronze), the first to dress formally (white tie and tails), the first to lose his virginity (backseat, ’65 Barracuda).

Unlike you, George went straight to college, but his career path was neither straight nor smooth. While an undergraduate studying oceanography at Drew University in New Jersey, he became an avid cyclist, a passion that had him competing in races long before Breaking Away and Lance Armstrong. From Drew he went to Auburn, and from there to the marine lab at Duke University, where he turned in his master’s thesis (“Sewage Mitigation via Ocean Outfalls”) a month ahead of schedule. From Duke he transferred to the University of Rhode Island to study marine biology.

While at URI, prompted by a knee injury sustained on a bicycling trip that forced him to pedal twenty-five miles home on one leg, he swam in Long Island Sound every day, often for miles against rip tides and stinging jellyfish. Once, he swam so far it took him three hours to walk home along the beach. (You, too, would become an inveterate swimmer, but it would take you a dozen more years.)

From marine biology your brother’s interests turned to aquaculture, and from there to agribusiness, and from there to economics.33

It was our father who urged George to turn to economics – having assumed, wrongly, that George would embrace and carry forward his socialistic views. Instead – and to our father’s combined horror and disgust – my brother embraced libertarianism.

At twenty-five, while you were bumming around with your backpack and guitar in search of your former English teacher, George earned his PhD. He would go on to become a world-class economist – invited by leaders of industry and nations to enlighten them on matters economic – and ultimately direct the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C.

* * *

STARTING WHEN YOU WERE CHILDREN AND CONTINUING on through your teens and beyond, you and George played a game together. In the game, one of you was a millionaire, the other a pauper. As a snowstorm raged outdoors the pauper scratched at the millionaire’s door. Meanwhile the millionaire, seated in his book-lined study, wearing a plush robe, sipped from a glass of port while smoking his pipe.

Though you took turns playing both roles somehow George’s version of this sadistic fantasy (in which he was the millionaire, and which, in recounting, he would score with appropriate hummed movements from von Suppé’s Poet and Peasant) was always more convincing.

In fact – and though he couldn’t have known it then – it wouldn’t be that far from the truth. There would come a day when, compared to you at least, your brother would be materially wealthy and successful; he would have a book-lined study in a sumptuously decked-out Victorian home. He would even puff on a pipe from time to time, though whether he did so in a plush robe you weren’t certain, and as far as you knew he wasn’t a port drinker.

Yet if there was envy between you and George it tended to flow from him to you. That George resented you was no secret; he told you as much on at least one occasion.

You were jogging together around the high school running track the morning after you’d both gone to a party thrown by a fellow high school student whose parents had both recently been killed in a car crash. You’d arrived late to find your brother talking to a pretty Asian girl, a foreign exchange student from China. You did your lone wolf Bohemian artiste act and ended up making out with her in the gone-to-seed garden.

You and George had rounded the track several times when he broke the silence:

You’re the kind of seductive charmer I envy, your brother said, panting. You’re also the sort of person that I never want to be like.

Your twin brother’s words filled you with self-reproach. You loved him, after all, in spite of everything. He was your mirror image. On the other hand you couldn’t help taking some pleasure in the fact that he envied you.

At times you wondered whether your brother’s decision to become an economist hadn’t at least to some extent been an equal and opposite reaction to your having elected to become an artist, if for him the appeal of economics lay less in anything positive than in its lack of obvious charm, a reaction to his disgust with superficially seductive ideas and people – people like you.

Had you not, after all, so far at least, charmed your way through so much of your existence, into the good graces not only of a certain English teacher but of others, too, including your father, who – according to George – always preferred you? Hence your twin brother’s distrust of and disgust for seduction in all of its forms. Thus for himself he chose the least seductive profession of all.

* * *

YOU (HOME FROM VISITING THE TEACHER AT HIS CARRIAGE house): Hey, George.

George (wearing headphones, listening to a record): Hey.

What’s up?

Nothing.

What album’s that?

Pet Sounds.

Oh. You just get it?

(George nods. You wait for him to ask where you’ve been. He doesn’t. You wait a bit longer before giving up and walking out of the bedroom.)

* * *

ONE DAY, DEAR PAST SELF, I’LL SHOW OUR BROTHER THE manuscript of this memoir. He won’t approve. He’ll point out some of its inaccuracies, how he began wearing glasses in first, not second, grade, that he didn’t throw up in Chinese restaurants at our father’s (or anyone else’s) urging. He’ll remind me that like me at first he wasn’t chosen for the teacher’s special class, he too had had to talk his way in. I won’t remember it like that, but he will be certain.

He’ll go on to say that he hasn’t read most of this memoir and he doesn’t intend to, that he disapproves of it on principle, that its mere existence pisses him off, as a matter of fact, so much that he doesn’t want to talk to me about it, doesn’t care to talk to me at all. For days he will avoid my phone calls and emails beseeching him to do so.

When he does finally consent to speak with me, what he will have to say won’t be pleasant. What he’ll have to say is this: that he’s fed up with being a minor character in what – as he sees me seeing it – is the epic of my existence, that though I may think I’m trying to do so, I can’t escape the inclination to make myself the center of my own drama. Newsflash: the world does not revolve around you, Peter, he’ll say.

He will go on to mention those periodic notices in local newspapers, in the Bethel Home News and the Danbury News Times, articles about your latest painting exhibitions and performances in plays, reports that, when they mentioned him at all, reduced him to a footnote. He’ll remind me of the time when, during a visit with our mutual friends in Vermont, we were discussing politics, how he, who had embraced Ayn Rand and her Objectivist philosophy, had been the lone defender of capitalism, how having excused himself to go to the bathroom (in fact he stalked off; I’ll remember that) he returned to find us all gone off to some bar.

You all just ditched me, he’ll say – noting that, all these years later, it still hurt.

Such things, combined with our socialist father’s contempt for his libertarian philosophy, further diminished your brother’s already imperiled sense of self.

But I’ve forgiven you, he’ll say.

As for my attempt at truth and reconciliation through composing “emotionally raw” memoirs, as far as our brother is concerned it’s pouring salt into old wounds.

I read ten pages, he’ll say. That was enough. A memoir written by someone trying to escape his own narcissism becomes itself an act of narcissism.

So our twin will say having refused to read the manuscript of this book.

OUR TWIN WILL be right and wrong: right to accuse us of trying to hog the lead, wrong to assume that role was ever ours. Whatever we did, dear Past Self, George always did it first. We’d marry, divorce, and have a child in that order; so would he, before us. We’d both move to Georgia and become professors in that state’s university system, but he’d get there twenty-five years sooner.

He’d be our closest confidant, this brother with whom we’d waken simultaneously from identical dreams, the person we turned to for solace and advice in times of distress or confusion, the person we looked up to more than we looked up to anyone else.

Including our father. Including the teacher.

Like them our twin played his role in inventing us. He helped engineer our fate. In opposition to your Bohemian dreams, he chose his path through life, sealing not just his fate, but ours, too. Since we were bound to follow him, our two hearts beating as one.

1 Today they’d call it ADHD.

2 The same community college in Bridgeport from which, according to his obituary notice, the teacher earned his associate’s degree.

3 It was our father who urged George to turn to economics – having assumed, wrongly, that George would embrace and carry forward his socialistic views. Instead – and to our father’s combined horror and disgust – my brother embraced libertarianism.