Читать книгу The Inventors - Peter Selgin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

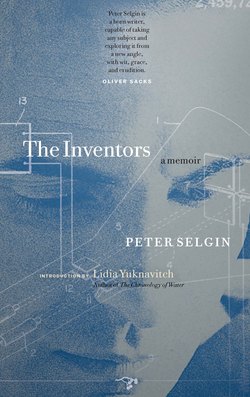

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Lidia Yuknavitch

A “PROXIMITY FUZE,” AN EVOLUTION OF THE “VARIABLE Time Fuze,” was a fuze that automatically detonated an explosive device when the distance to a target became less than what had been programmed. Proximity fuzes were better than timed fuzes, which could go wrong in a myriad of ways. More precise. Less human error. Clusters of ground forces. Ships at sea. Enemy planes, various missiles, suspected ammunitions factories. Those were most often the targets.

And hearts.

At the heart of this book is a proximity fuze in the form of two men who entered and detonated Peter Selgin’s life, leaving him to reconstitute a self from the pieces that were left. When we think about the people who come into and out of our lives, there are only a few – or less – who literally rearranged our DNA. You know what I’m talking about. Those people who, for whatever reason, detonated our realities. For Peter Selgin there were two men, one his father, who helped develop the proximity fuze, the other a teacher, who not only changed his life forever, but who had something in common with Selgin’s father: they lied their way to selves.

I’ve always hated the word “lie.” It has a bomb in its center. The bomb has a kind of morality trap inside of it. When we point to someone who “lied,” we can more easily condemn them while feeling better about ourselves. And yet everyone I have ever met has lied. Sometime, somewhere. It’s human to be bad at telling the truth. Truth is difficult and painful and often self-incriminating. I prefer the word “fiction.” It allows for the fact that all of our truths – the stories we tell ourselves so that we can bear our own lives – are always already constructed. Our life fictions are compositions made from memory, and memory, as neuroscience now tells us, has no stable origin or pure access route.

I happen to be an expert on the topic of lies. My mother lied to me. My father lied to me. My family was a lie, my religion was a lie, husbands lied, teachers lied, friends and foes lied, the selves I was meant to step into – girlfriend, wife, mother – were all strange cultural fictions. Writers live within language, and so in some ways, you might say we are at the epicenter.

Peter Selgin’s father was a brilliant man who participated in the extraordinary inventions but also the death sciences that culminated in the atomic bombs used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In order to forge a self he could live with, he fictionalized his own past. And because life is always bringing the same trials back around to us in different forms, later in his life Peter Selgin would meet another man, a teacher whose fictions recreated a self that might rise above the human wrongs he’d committed. Peter writes from within the epicenter of each.

This story is about what we make and how we make it: selves, lives, love stories, life stories, death stories. It is also the story of how creation and destruction are always the other side of each other, and – like the lyric language so gorgeously invented in this book that it nearly killed me – its meanings are endlessly in us. It’s a book about how we do and do not survive our twin forms of being: the selves we live, and the stories of those selves we endlessly recreate. And there is something at the heart of the story that I did not expect to find.

Hope.