Читать книгу Origami Odyssey - Peter Engel - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

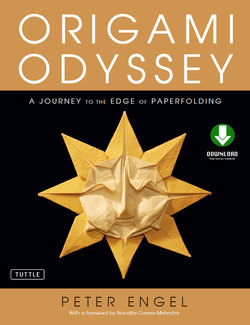

ОглавлениеGiven the breath of life by M.C. Escher’s extraordinary imagination, this mischievous reptile aspires to live in three dimensions but is condemned to return to the inanimate tile pattern whence it came.

In Search of Form and Spirit: An Origami Odyssey

Why am I—and why are you, the reader of this book—drawn to origami? There are, after all, more popular arts we could pursue: painting, sculpture, photography, poetry, dance, or music, each possessing a fine Western pedigree. When I was a child of twelve or thirteen, just developing a fascination with paperfolding, I didn’t question what drew me to it. I only knew that with each new figure that formed in my hands (at first other people’s designs, and then my own), I felt the pull of having entered some other, deeper world.

I didn’t have the words then to describe this experience, but today I would say that it involves magic, alchemy, the transformation of something common (a piece of paper) into something rarer than gold—something living, a bird or a beast or a human figure. Some arts are additive: an oil painting is built up stroke by stroke, a musical composition note by note, a work of literature word by word. Others—a woodcut, a stone carving—are subtractive: the artist strips away wood or stone until the desired end state is reached. But origami is transformative. There is just as much material at the beginning as at the end. Unfold the completed origami figure, achieved entirely without cuts, glue, or other impurities, and you return to the original square. If that’s not alchemy, nothing is.

The Dutch artist M.C. Escher, one of my early influences (I remember being mesmerized by a lithograph of his in a magazine around the time I encountered origami), had an expression for what drew him to the tile patterns that he transformed, bit by bit, into representational figures. He called it “crossing the divide,” the divide between that which he called “mute”—meaning abstract, geometric shapes—and that which “speaks,” something living and breathing. Escher’s artistic process gives life, gives breath. The geometric shape turns into a fish, then a swan, flies from the paper, then returns to become a shape once again. Alchemy.

Escher’s philosophical musing has a parallel in a wood-block print by Katsushika Hokusai. In A Magician Turns Sheets of Paper Into Birds (1819), the pieces of paper tossed into the air by a seated magician evolve into a more and more birdlike form until at last they take flight. Hokusai, like Escher, brings the inanimate to life. By crossing the divide in the other direction, however—returning animate forms to their abstract, geometric origins—these artists simultaneously undermine the reality of their creations’ existence. In Escher’s lithograph Reptiles (1943), the lizard that emerges from a hexagon thinks it is alive—in Escher’s exquisitely rendered image, it appears completely three-dimensional and palpable, and even gives a little snort—but before long it becomes two-dimensional again and then mutely, and meekly, regresses to the hexagon whence it came. If the lizard isn’t real, how do we know that we are?

In my teens and early twenties, I was captivated by form and pattern, and the origami models I devised during that time aspired to geometric perfection. In my designs from that period, such as a lumbering elephant, a leaping tiger, a prancing reindeer with a full rack of antlers, a scuttling crab, and a sinuous octopus with eyes and a funnel for shooting ink, I strove to discover the seemingly limitless potential contained within a single square of paper. (These models appear in my first book, Folding the Universe.) To generate figures as elaborate as these, I drew on an age-old tradition in paperfolding, adding layer upon layer of complexity to basic forms devised by the two cultures that elevated paperfolding to a high art, the ancient Japanese and the Moors of medieval Spain and North Africa.

The square, with its many symmetries, lends itself to capturing these complicated but ultimately symmetric shapes. I applied geometric operations such as reflection, rotation, change of scale, and the grafting of one pattern onto another to generate complex forms from simple ones. Unfold any of these models to the original square, and the profusion of legs, tusks, antlers, tentacles, and antennae melts back into an orderly, geometric pattern. Indeed, it has to, or the paper would not fold compactly enough to produce so many long, thin appendages. Out of this structural need for efficiency is born origami’s aesthetic of economy. Indeed, the pattern visible in the unfolded sheet is striking and beautiful.

These early models made a virtue of rigor and a kind of determinism. The more the completed design appeared inevitable—the more the entire model appeared to develop from one initial impulse, without a single crease left to chance—the more I prized it. In writing about the virtue of geometric rigor in Folding the Universe, I drew a parallel to the well-wrought piece of Western classical music. The first movement of Johannes Brahms’s Fourth Symphony, which I cited as an example, unfolds inexorably, and thrillingly, from the very first two notes, then develops, recapitulates, and culminates in a shattering climax. It is still a piece I love, and even today, artistic rigor, whether in music, architecture, or origami, exerts an enormous pull on me, and is reflected in some of the models in this book.

Katsushika Hokusai’s wood-block print A Magician Turns Sheets of Paper Into Birds captures the alchemical transformation that takes place in the creation of an origami model.

A Japanese Pilgrimage

I had already spent a decade creating my own origami figures when, at the age of twenty-three, I traveled to Japan to meet and interview that country’s greatest origami artist, Akira Yoshizawa. (The interview appears in Folding the Universe.) Without Yoshizawa, whose brilliance and fame popularized origami and made it an international art form, folding paper might still be solely the province of Shinto priests, the Japanese aristocracy, and Japanese schoolchildren.

In the style of a young apprentice to an aged sensei, or master (Yoshizawa was then about 70), I drank from Yoshizawa’s pool of ancient wisdom, even as I remained skeptical of his mystical pronouncements. As a recent college graduate on that first trip to Japan, I was seeking life experience, a way of moving beyond the limitations of an insular life spent mostly in studies. Like many young graduates, though, I simultaneously cast a critical eye on patterns of behavior different from my own, and Japanese culture had plenty to critique. The elder Japanese origami sensei whom I met on that visit (Yoshizawa among a half-dozen or so) seemed eccentric in their single-minded devotion to folding paper and narcissistic in their need to surround themselves with true believers who only practiced their particular school of folding. But there was no denying the brilliance and vitality of Yoshizawa’s models and of the man himself (in person, jumping up on a table to retrieve boxes of models on high shelves, or imitating the movement of an octopus, he didn’t seem old at all), and I began to open up to the wisdom he had to offer.

Play is at the heart of every origami design. The sheer delight of bringing a form to life in your hands, common to child and artist, breathes spirit into the creation. When the unconscious takes over, play begins. Forward-thinking educator Friedrich Froebel, the inventor of Kindergarten, understood the value of play in learning and made paperfolding a core component of his curriculum.

Play and tradition merge in this image of a folded crane on a Japanese noren, a cloth hanging.

Years later, I realize that the lessons of that first trip to Japan have never left me. Yoshizawa taught me to listen to nature (water always knows which way to flow); to know both who you are and where you want to go (a compass is no good if you don’t know your destination); to heed the interconnectedness of all things (all living creatures inhale the same air); and perhaps most importantly, always to seek the hidden essence, since what we experience with our senses is just the surface, a thin veneer. It is no stretch to see a connection between Yoshizawa’s Zen musings on the impermanence of all things (among them, paper) and the short-lived earthly existence of Escher’s lizard, with its endless cycle of birth, death by geometry, and rebirth.

I found echoes of Yoshizawa’s deeply felt beliefs in the other Japanese arts and crafts I encountered on my journey, all of which resonated deep within me. Like origami, they cultivate an aesthetic of understatement, of suggestion. Just as a three-line haiku evokes a setting or a season, the glancing stroke of an ink brush potently realizes a craggy mountain peak or an aged hermit, and the placement of a rock and a pond in a Zen garden recalls the universe. It is a short imaginative leap from the rock to a mountain, from the pond to the sea.

The ink on the paper and the rock in the garden appeal to us as beautiful forms, but I have come to realize that what really captivates us is something subtler and deeper—for lack of a better word, their spirit. We sense that there is something mysterious and profound going on, that these forms are really a window to a layer beneath. There is a tenuous balance between form and spirit. If the outer layer takes itself too seriously—believing itself to be too real, like Escher’s all too self-important and too three-dimensional lizard—it risks having its own reality undermined. The gravel and rock garden at Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto is profoundly powerful and suggestive in a way that an American miniature golf course, with its “realistic” miniature buildings and tinted blue waterfalls, is not. Likewise, an origami model that is too real, too exacting, loses the illusion and the charm—and, with it, the alchemy.

I can probably trace to this first journey to Japan my subsequent, lifelong immersion in Asian art and culture. Research and architectural work have since taken me to India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, China, Hong Kong, Myanmar, the Philippines, and back to Japan. I can hear echoes of Yoshizawa’s pronouncements in my fascination with Indian and Indonesian shadow puppets, which come to life only when their shadow is projected on a screen; with the ancient Sri Lankan hydraulic system that irrigated that country’s flat dry zone using gravity alone (a version of which my wife and I employed in our design of a peace center in Sri Lanka); with Indian ragas that can only be performed at dusk; and with Hindu holy verses that cannot be read out loud, only sung.

Crossing the divide, reality and illusion, interconnectedness, hidden essences, impermanence: I was fortunate as a young man to have been exposed to these enduring and challenging concepts by deep thinkers who made them palpable in their art. These are not qualities American culture values or perhaps even recognizes. As I look around at the state of my country today and our effect on the wider world—our obsessive concern for the here and now, our disregard for nature, our inability to recognize the interconnectedness of all living and non-living things—I see the exact opposite of what Yoshizawa was trying to teach, and it is hard not to be saddened. When Yoshizawa died a few years ago, at the age of 94, I felt a great loss, even as I knew that he would have been the first to remind me how brief is our transit here on earth.

Proud as a peacock, origami master Akira Yoshizawa retained his childlike sense of play into his 90’s. Here, in his early 70’s, he shows off one of his favorite origami creations at our first meeting thirty years ago.

An Indian Journey

Following the completion of my graduate architectural training and the publication of Folding the Universe two years later, I took an extended break from paperfolding. Folding the Universe proved to be an exhaustive, and exhausting, summation of my early design work and the concepts that had informed it. At the book’s completion, I found myself at an artistic impasse—not the first, as the book attests, nor the last. The geometric rigor and determinism that had informed my early designs had come to feel vacant and soulless. Like Escher and Hokusai, I had experienced the illusory nature of aspiring to perfection. And while my exposure to Yoshizawa’s artistic philosophy and Japanese aesthetics had reinvigorated me, I had neither the desire nor the cultural background to follow in Yoshizawa’s footsteps.

And then the opportunity arose to travel to India. With the aid of several research grants, my wife, Cheryl, and I spent a year criss-crossing the country as she investigated India’s extraordinary underground buildings and I researched that country’s vernacular architecture, the buildings and places made by ordinary people. As we journeyed through mountains, forest, and desert and from teeming city slums to remote, tiny villages, we were exposed to India’s extraordinary crafts traditions and met some of the country’s finest weavers, woodcarvers, brass smiths, potters, bas relief sculptors (to decorate the interior of a desert house, they mold a mixture of mud, straw, and dung), and makers of leather shadow puppets. The work of India’s craftspeople possesses a rough, elemental power, often revealing the actual imprint of the maker’s own hands.

Craft requires that the maker of an object respect the nature of the materials at his service. The limits imposed by the size, shape, thickness, and texture of the medium inspire the creator of a pot, rug, tool, or origami design to create an object of function and beauty.

A woven wicker ball from Java, Indonesia and a copper and leather “monkey” drum from Patan, Nepal are two of many crafted objects that have inspired my origami designs. They evoke the spirit of play not only in the finished products but also in their creative design and skillful execution.

Meeting these artisans allowed me another opportunity to reflect on the craft of origami and how it had come to be practiced in the United States. The passion, artistic vision, and technical refinement that Indian craftspeople bring to their work are the outcome of centuries-old traditions passed down by word of mouth from father to son and mother to daughter. Each piece of craftsmanship expresses a culture’s repository of religion and folklore while simultaneously allowing the artisan a limited amount of freedom to explore his or her own creative ideas. And while the created object is ornamental and decorative, it is also practical: something to be worn, to carry food or water, to create music (the ghatam, an ancient south Indian instrument, is a specially fashioned clay pot), to serve in a religious ceremony.

The same could certainly be said of Japanese crafts and of origami as it was practiced in Japan for most of a millennium. But when Westerners took up origami around the middle of last century, they chose to appropriate the technical rather than the cultural aspects of Japanese folding. Such uniquely Japanese traditions as the thousand cranes, the Shinto shrine, the tea ceremony, and the strict master-disciple relationship meant little to the new self-made folders of the Americas and Europe; instead, they seized upon the geometry of the kite base, fish base, bird base, and frog base as if it had always been their own. Western paperfolding began with a powerful set of mathematical relationships but little or no cultural tradition in which to ground them.

I came to realize that my own origami designs fell squarely in the middle of this traditionless Western tradition. Unlike Japanese origami or the crafts I encountered in India, most of my early creations had no historical origin, no set of cultural associations, and no utility: they were objects to be seen, not used. They arose not from a collective, cultural wellspring but rather my own, individualized response to principles of geometry and to creatures that I had seen only in aquariums, zoos, or—stuffed—at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. (In India, the depictions of tigers, elephants, and monkeys are often based on encounters in the wild.) Whatever aesthetic delight my creations afforded the viewer arose from their finished form and the technical ingenuity required to fold them, not from a shared, empathic relationship between the viewer and the creator.

Typical New Yorkers are oblivious to origami design on phone booth.

Memories of my childhood in New York state brought to life these three scenes of Montauk Lighthouse, the Adirondack Mountains, and a Sailboat in a series I designed for the New York State Department of Tourism. The finished versions were folded from the tourism brochure, and photographs of the models appeared on telephone booths and billboards throughout New York City. The lighthouse cottage appears in this book.

Seen in perspective, the mountains reveal the irregular crags and promontories, the order mixed with improvisation, of their counterparts from nature. They employ a spiraling sequence of closed-sink folds that avoids unnatural-looking horizontal or vertical creases. The folds are similar in shape, but because they rotate and reduce in size with each turn, no two faces of the mountain are the same, and the resulting origami models appear natural and asymmetric.

Many of my earlier models exhibit a high degree of symmetry. The pattern of creases in my model of an Elephant reveals mosaics of repeating shapes. The taut geometry reflects an efficient folding process, necessary to achieve the elephant’s pointed tusks and tapered trunk (with tiny “fingers” at the tip).

A Mysterious Affinity

Along with Indian crafts, I found myself deeply influenced by Indian music, from the classical ragas I heard performed by renowned musicians such as L. Shankar and Zakir Hussain in a Mumbai concert hall to the powerful, rough-hewn folk music I heard sung by the goat- and camel-herders of the plains and deserts. Classical Indian music has a completely different quality than most Classical Western music. Often meditative and dreamlike, it can give the sense of being in motion without going anywhere. Evoking the paradox of the raga’s journey, the Indian music critic Raghava R. Menon writes in Discovering Indian Music, “Its possibilities are infinite and yet it always remains unfinished. Its ending is always a temporal ending . . . In the immediate present, there is no perfection, no consummation, nothing is finished . . .We can see the invisible in it, laden with mystery and revelation, candidly open in its transit . . . It does not want to get anywhere. It just takes place.”

In contrast to the perfection and inevitability of a piece of Western classical music like Brahms’s Fourth Symphony, whose entire score is written out note by note for the musicians to perform, an Indian raga is always improvised. A raga begins with the sound of a tanpura, or drone. There is as yet no rhythm, no measured beat, no pattern. One could say the drone is the sound of the universe before the beginning of time. Out of this hallucinatory mood emerges a second instrument, possibly a sitar or sarod, which weaves melodies hypnotically in and around the drone. And then, with the introduction of the tabla, with the first drum beat, comes the beginning of a kind of order. It is a very complex order, with highly varied patterns of beats that initially sound quite strange to Western ears. Other musicians enter, and the raga becomes a dense, polyphonic intermingling of voices. Like a piece of Western classical music, a raga has a complex structure, but the structures are completely different, reflecting the very different relationships in India and the West between man and nature. Menon writes, “The Indian ethos postulates the existence of a reality behind the appearance of things, a mystery that lurks in the core of all created things,” and goes on to add, perceptively, “The delight of Indian music, then, lies in the search for this elusive, mysterious beauty, not in its ‘finding.’ If this delight is transferred to the ‘found’ beauty from the search for new beauty, a sudden loss of vitality, a facile sweetness begins to show, and a superficial estheticism takes over.” It is not hard to hear, in Menon’s description, echoes of Yoshizawa’s belief in unseen essences and beauty that can only be found beneath the surface.

Using imagination and the power of suggestion, two Japanese artworks evoke differing moods of water: a raked-gravel Zen garden and an interpretation of Hokusai’s wood-block print View of Mount Fuji Through High Waves off Kanagawa from the cover of Claude Debussy’s printed score for La Mer. Debussy owned a copy of the print and chose the image himself.

My exposure to Indian crafts and music gave urgency to my struggle to escape the hegemony of geometric determinism in origami. I gained conviction, too, from the music and writings of a couple of Western classical composers whose works I had loved but perhaps not fully understood. Western composers began to absorb Asian influences into their music at the end of the 19th century, a time when the French composers Claude Debussy and Erik Satie struggled to break free of the Germanic determinism that had dominated classical music from Beethoven through Brahms and Wagner. While some British and Central European composers looked to native folk traditions, Debussy and Satie turned primarily to inspiration from ancient Greece, medieval mysticism, and the exotic sounding harmonies and rhythms of the Far East.

Although Indian music was little known, the appearance of a Javanese gamelan orchestra at the 1893 Paris Exposition had a mesmerizing effect on Debussy. A keen collector of Japanese woodblock prints and other Asian objets d’art, Debussy began to experiment with the pentatonic scale (Satie was doing much the same with medieval scales), generating indeterminate and unresolved harmonies that possessed, in common with much Asian music, a kind of static motion. Much of the music that Debussy produced has subtle correspondences with nature and human experience—famous examples include the piano works The Sunken Cathedral, Pagodas, Evening in Granada, Goldfish, Reflections in the Water, and Gardens in the Rain, with perhaps his most famous work being the orchestral La Mer (The Sea)—but he rejected the notion that he was a mere “impressionist,” preferring to think of himself instead as a “symbolist.” In an incisive note about the creation of his opera Pelleas and Melisande, Debussy wrote, “Explorations previously made in the realm of pure music had led me toward a hatred of classical development, whose beauty is solely technical . . . I wanted music to have a freedom that was perhaps more inherent than in any other art, for it is not limited to a more or less exact representation of nature, but rather to the mysterious affinity between Nature and the Imagination.”

Working nearly in parallel with Debussy, Satie was exploring the balance of stasis and movement in his own piano pieces and songs and undermining the seriousness of the Germanic tradition by marrying his profound mysticism to an absurdist sense of humor. He provocatively titled a set of piano compositions Three Pieces in the Form of a Pear to prove to his close friend Debussy that his music really did have form. (Pointedly there are seven, not three, pieces in the collection.) The same Zen-like mind later produced Vexations, which consists of a single musical theme repeated 840 times. Satie’s “white music” and Zen utterances would eventually inspire the aleatoric, chance-inspired music of the American composer John Cage, who with a team of pianists first performed Vexations seventy years after it was composed, in a performance that took over 30 hours. Satie’s deliberate disconnect between the name given to a piece of music and the music itself recalls the paradoxes evoked by Escher’s reptile and Hokusai’s magician, calling into question which is reality and which illusion.