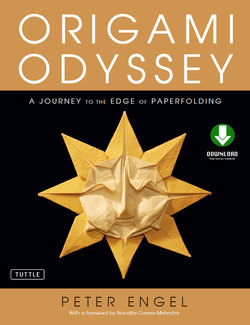

Читать книгу Origami Odyssey - Peter Engel - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

by Nondita Correa-Mehrotra

How wonderful it is to fold a simple square sheet of paper! A square is perhaps the purest shape, and through the elementary act of folding this sheet, we can create an object. There are no implements, no tools for measuring. This is why the origami models I enjoy most are those that clearly relate back to the square paper I began with, like the elegant crane we all learned to make. The steps to create it are few and the time taken so little that I am amazed at how quickly I can craft this bird!

However, as one progresses to the more complicated models, like the complex insects with perfectly proportioned legs and antennae, the skill and deftness required can often be very demanding. That, I suppose, is what defines the more advanced paperfolder from the beginner. Yet, what fascinates me about origami is not necessarily that kind of complexity. Rather, it is the straightforwardness that I strive to find, the purity in the ideas that created it. The ideas I am talking about are really ones that a paperfolder infuses into his model—be they ones that push the medium of the paper and the rigor of the folds, or, as Peter Engel eloquently describes in his essay in this book, “the spirit.” And when you see origami in this context, you realize that in simplicity there is simultaneously a surprising complexity, running like an undercurrent, stemming from the ideas that the folds and processes explore. It is important to define these ideas, for as Henri Matisse said, “Much of the beauty that arises in art comes from the struggle an artist wages with his limited medium.” This is so true of origami, as the medium is extremely limited, the parameters tight. The one thing in our control is the folding itself.

Of course, one of the most beautiful and gratifying aspects of origami is undoing all the folds and analyzing the square again. It is abstract, yet clearly has an intense correlation between what you had just made and the process of folding. The sheet unfolds almost flat, but for the folds that once were. “A fold changes the memory of the paper,” explains Erik Demaine, a mathematician and one of the world’s foremost theoreticians on origami. The memory of the paper—that’s a beautiful thought!

And when the paper is unfolded and yet carries the memory of the first set of folds, could we use it to make a completely different object, with a different set of folds? Like a palimpsest, if we were to reuse the once-folded sheet, how would one pattern, one set of instructions influence the other? What happens to the new object? In my mind, I understand the folds and the memory of them on the square sheet of paper as being the dominating mechanism in origami.

As remarked by Correa-Mehrotra, a folded sheet of paper records a memory of the folding process. Shown at left the author’s origami Reindeer and above the pattern of creases that results when the paper is unfolded. The dense pattern of lines at top corresponds to the nose, ears, and antlers.

Whatever we make, whatever models we construct, we learn from them, and in turn we can better what we make. In his essay, Engel talks about connecting oneself to one’s craft, and as both an architect and a paperfolder, he is able to relate these sensibilities to his models. We each try and relate what we make to what we know. As an architect I feel that unfolded, flattened paper, with its creases yet visible, reminds me of an architectural plan—from which I can understand the structure and the nuances of the object. Yet a difference does exist, for there is a physicality prevalent in origami that is missing in architectural orthographic drawings. The fact that the paper has to be folded manually is a tactile exercise, one that forces us to think the process through.

For several years I taught an architectural undergraduate design studio in which one of the assignments was to make what I called a “lightbox.” It was a mechanism for capturing light and was made by the students from a single sheet of white Bristol board paper. The sheet size came in 22.5” x 28.5” and they were required to use the entire sheet. Although they were allowed to cut and fold, they could not use any adhesive. Only the folds had influence and stiffened the structure. The students made amazing forms and watched how light behaved without and within. And finally when we unfolded the “lightboxes” to understand the process, the paper recounted to us its memory!

This exercise also introduced the concept of economy of material, of using every part of the sheet—something origami is so rigorous about. As Engel says in his essay, while other art forms are either additive or subtractive, “origami is transformative.” And he rightly, I think, compares this attribute to alchemy, for there is as much material at the beginning as at the end, and so you can go back to the beginning without losing anything. This capacity to create something with care and determination (and no waste) is unique. Without that objective, that intent to create something of consequence, you could just as easily scrunch up the paper and call it abstract art!

The author’s origami Hatching chick, shown at right, and the memory of its folding process, captured in the crease pattern above. The white egg opens to reveal the yellow chick, produced from the opposite side of the paper.

Nondita Correa-Mehrotra

Boston

October 2010

Nondita Correa-Mehrotra, an architect working in India and the United States, studied at the University of Michigan and Harvard. She has worked for many years with Charles Correa Architects/Planners and is also a partner in the firm RMA Architects in Boston.

Correa-Mehrotra has taught at the University of Michigan and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She was one of five finalists for the design of the symbol for the Indian Rupee, an idea she had formulated and initiated with the Reserve Bank of India in 2005. She also designs furniture, architectural books and sets for theater, and curates exhibitions.