Читать книгу Pete Townshend: Who I Am - Pete Townshend - Страница 10

Оглавление6 THE WHO

In 1964 I began playing guitar the way I was always meant to play it. The sound I had favoured until then borrowed liberally from American prodigy Steve Cropper’s guitar solo on ‘Green Onions’ – a cold, deeply menacing, sexual riff. This, I suppose, is how I imagined myself at eighteen. Now, at the flick of a switch the central pickup, which I had set close enough to the strings to almost touch them on my modified Rickenbacker 345S guitar, cut in to boost the signal 100 per cent. The guitar, with a semi-acoustic body I had ‘tuned’ by damping the sound holes with newspaper, began to resonate.

By April I was so tired and distracted at school that the lecturer running the Graphic Design course at Ealing, a big-shot ad-man, asked about my health. In my second year of Graphic Design, my fourth year at college, I was, according to him, producing good work. I told him my work with the band was exhausting me.

‘Do you like it?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Well, how much do you earn?’

When I told him around 30 quid a week, he was stunned. At nineteen I made more money than he did. He suggested I might be better off pursuing the band, which was the beginning of the end. After gigs I found it harder and harder to get up the next morning for class, and at some point before the summer break of 1964 I stopped going to college at all.

My musical self-certainty drove me blindly forward. I felt I was hauling a band behind me that was ill-suited to the ideas drummed into me at college, but it was a better vehicle than the conventional life of a graphic designer. I wasn’t trying to play beautiful music, I was confronting my audience with the awful, visceral sound of what we all knew was the single absolute of our frail existence – one day an aeroplane would carry the bomb that would destroy us all in a flash. It could happen at any time. The Cuban Crisis less than two years before had proved that.

On stage I stood on the tips of my toes, arms outstretched, swooping like a plane. As I raised the stuttering guitar above my head, I felt I was holding up the bloodied standard of endless centuries of mindless war. Explosions. Trenches. Bodies. The eerie screaming of the wind. I had made my choice, for now. It would be music.

The time had also come when we realised we had to work full-time as musicians or we would be unable to compete with the likes of the Stones, The Beatles and The Kinks. Moonlighting was no longer enough. It had become essential, too, that we get our sound right.

I sought the wisdom of Jim Marshall, who would become the inventor of the Marshall stack, the high-powered amplifier systems used by most heavy-rock guitarists since the mid-Sixties. Jim ran his music shop in West Ealing. John Entwistle, one of Marshall’s first customers, was very happy with his new cabinet of four 12-inch speakers intended for bass guitar. I was less thrilled. John, already very loud, was now too loud. I bought a speaker cabinet and powered it with a Fender Bassman head. John bought a second speaker cabinet to stay ahead of me. I quickly caught up with two Fender amplifiers, the Bassman and a Pro-Amp driving two Marshall four-by-twelve speaker cabinets. John and I were in a musical arms race.

I was the first electric guitar player on our circuit to use two amplifiers at the same time, and I only heard much later that my then hero Steve Cropper of Booker T and the MGs sometimes recorded with two amplifiers back to back. The distortion factors introduced by each amplifier became much more complex and rich when fed back reciprocally. I had also begun to pile one Marshall speaker on top of the other to emulate the conditions at the Oldfield Hotel hall where I had first put a speaker on a piano in very close proximity to where I stood playing the guitar, creating feedback. This configuration is what later became known as the Marshall stack. I remember Jim trying to talk me out of it at first, telling me they could topple over and kill someone. The first cabinets I had were clipped together with heavy luggage clips he provided. Over a period of months I persuaded Jim and his team to make his amplifier not just louder but also brighter sounding, and capable of more distortion when pressed hard.

In rock ’n’ roll the electric guitar was becoming the primary melodic instrument, performing the role of the saxophone in jazz and dance music, and the violin in Klezmer. I began using feedback more creatively; sometimes my guitar solo would simply be a long, grinding howl full of evolving harmonics and whistles. But in its enormity I discovered something euphoric, a sound full of movement and cascading melody. This is something that later exponents of electric guitar feedback explored far better, especially Jimi Hendrix.

Oddly, I felt some shame too during these droning moments, but not for any self-indulgent act of musical desecration. In truth I had no idea what the origin could be of all the contradictory emotions I felt when creating these warlike sounds. Something was bubbling up from my subconscious mind.

Jim Marshall had struggled to impress his father, a boxer, and failed. By one of those strange quirks of fate, on the occasion of Jim’s last performance as a drummer my dad was playing with him in a small orchestra Jim had put together. Jim’s father arrived drunk, and began to taunt his son from the floor. Suddenly Jim lost his temper, flew at his father and beat him badly, even though the older man was much more powerful. Jim never played the drums professionally again.

I was experimenting all the time, trying to find new ways to play my guitar on stage, inspired directly by Malcolm Cecil. He had demonstrated unusual ways of playing his double bass, in one case breaking a string, then being challenged by being given a woodsaw which he bravely used to cut through the rest of the strings, damaging the surface of his instrument. I fell upon my Rickenbacker with all manner of scraping, banging, bending and wrenching, which resulted in howling acoustic feedback. Encouraged too by the work of Gustav Metzger, the pioneer of auto-destructive art, I secretly planned to completely destroy my guitar if the moment seemed right.

The Who still seemed like a temporary, disposable part of my private plan. We would chop away at our own legs. Certainly, R&B on its own didn’t seem to me enough of a new idea; it was just the emerging bandwagon predicted by the music papers. On stage I was becoming increasingly anarchic and narcissistic; film of the period shows me spending more time moving my hips than fingering notes. But I also copied neat solos by Kenny Burrell, the jazz guitarist. Had I studied properly and practised more conventionally in these years, I would have become a more proficient guitar player and less of a showman.

During this period I often looked effeminate. Since I’d never really had a steady girlfriend, rumours went round that I might be gay. In some ways I felt happy with this. Larry Rivers proved to me that a gay man could be wild, attractive and courageous; in any case one’s sexuality was becoming less of an issue every day. One of the great things about the British Mod movement was that being macho was no longer the only measure of manhood. I myself had no interest in appearing attractive, much less sexual, on stage; in the end all the disturbing experiences of my childhood went into my composing.

One day a girl came to claim all the albums that belonged to Cam, bringing a letter from him confirming that this was his wish. It affected our collection badly. A little later we received instructions from Tom to package his albums and send them to him in Ibiza. These back-to-back losses were difficult to deal with. Suffering from music withdrawal, I began to collect albums myself, replacing all I could find, but many were rare. Barney and I discovered Bob Dylan, and listened intently to his first two albums. There was something extraordinary there, but I wasn’t sure what it was.

Barney and I had been living in total squalor, and then we lost the lease to the flat altogether. Mum, always alert to a way to fix things for other people, discovered that the tenant in the apartment immediately above the Townshend homestead at Woodgrange Avenue was leaving. She secured the lease and Barney and I moved in. It was a splendid, rambling place. The rent was £8 a week, and we had five wonderful rooms, a bathroom and kitchen. I began drawing elaborate, ambitious plans to develop the place into art rooms, a recording studio and recreation rooms. But it was hard snapping out of our squalid living habits. We didn’t purchase a single item of furniture and slept on single mattresses on the floor. We discovered an extremely heavy material in sheet-board form that we intended to use to soundproof one of the rooms and we filled one entire room with it, but never even started any of our schemes.

We continued to get stoned and listen to records in bed, allowing the detritus of our existence to pile up until we could persuade someone else to tidy up for us. Newspapers, food cans, cigarette butts and dirty coffee cups littered the room we slept in and used to entertain visitors. When hungry I simply went downstairs and took food from my parents’ cupboards. People came and went – art-school mates, girls we knew, and occasionally a compliant waif-fan from a show. I was still quite shy, and although no girl complained when we did have sex, I never really felt on a par with the other guys in the band who seemed such old hands.

I developed quite an unpleasant streak at this time (I have this on good authority from my friends). I became increasingly critical and cynical, and in arguments often twisted the facts to fit my brief. I adored Barney, but he too was growing cynical. Perhaps we were smoking too much grass. I remember the apartment we shared shrouded in a grey pall. The stuff we were buying was certainly getting stronger.

Doug Sandom’s sister-in-law Rose found us a benefactor in Helmut Gorden, a single man who wanted some excitement in his life. He became our manager, bought us a van and introduced us to some major agents who booked us shows here and there. Otherwise we continued to play the local pub circuit in our immediate neighbourhood. Unknown to us, Commercial Entertainments, who had promoted most of these local shows, had decided to put The Who under contract, but my parents had refused to sign anything on my behalf.

Helmut Gorden managed to get us an audition with Fontana Records, not knowing that Jack Baverstock, chief of the company at the time, was one of Mum’s closest friends. She put in a word for us. Fontana’s A&R man, Chris Parmienter, heard us play in a rehearsal room and liked us, but he felt our new drummer, Doug Sandom, was too old.

Seeing our chance at a record deal fading, I cold-bloodedly announced to the band that I felt sure Doug would want to stand down. Doug was deeply hurt by this, especially because, unknown to me, he had defended me against my being thrown out of the band a few months earlier when another auditioning agent said I was gangly, noisy and ugly. Doug did stand down, with some dignity, so we got our break. It is one of the actions of my career I most regret. Doug had always been a friend and mentor to me, not to mention he was the first person to get me really drunk.

We tried a few new drummers, including Mitch Mitchell, who went on to play with Jimi Hendrix. But Keith Moon appeared one day at one of our regular dates at the Oldfield Hotel in Greenford, and as soon as he began to play we knew we’d found the missing link. He told us his favourite drummer was Buddy Rich, but he also liked British bandleader Eric Delaney, who used twin bass drums. He failed to mention until much later that he was an obsessive fan of Californian surf music, but the band he was playing with was called The Beachcombers, so we should have guessed.

Keith had been taking lessons from Carlo Little, the drummer with Screaming Lord Sutch, who was a performer from the previous wave of novelty bands on the small gig circuit. An eccentric player, Keith seemed to be showing off all the time, pointing his sticks up in the air and leaning over the drums, face thrust forward as if to be nearer the front of the stage. But he was loud and strong. Slowly, too, we realised that his fluid style hid a real talent for listening and following, not just laying down a beat.

Roger tried to befriend Keith, but Keith kept his distance. He also seemed to see Roger’s success in pulling girls at our gigs as a challenge. They sometimes chased the same girls in those early days, and it was never clear to me who was winning. I wasn’t sure how Keith felt about me in the first few months he was in the band, nor whether he’d support my arty manifesto; time would tell. Keith’s main pal in the band became John. They were hysterically funny together, and shared an apartment for a while. Roger and I got the impression they did almost everything together, including having sex with girls. It must have been mayhem.

Despite the pain I had caused by my disloyalty to Doug, it became clear that with Keith Moon in the band and a new record deal we had a real chance at a career in music. I had already written a couple of decent songs, and was using an old tape recorder to write new ones in the style of Bob Dylan. Through a friend of Helmut Gorden we met Peter Meaden, a publicist who seemed to know all the teenybopper magazine editors. Peter was much impressed by the antics of Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, who had a tough henchman who acted as his protector and sometimes enforcer. So Meaden found one of his own in a chap we came to know as Phil the Greek, who was sharply dressed and good-looking, with a vicious streak. He and I became quite good friends.

What Peter Meaden did do for us was to enact a thesis Barney and I had already gleaned at art school: every new product, including every new band, needed an image if it was to succeed. That is, we needed an identifiable style: outfit, haircut, and if possible a new way of making music. Barney, his girlfriend Jan and I talked late into the night about how to capitalise on this extraordinary time; we were smart, and we had a band that might make good if we got things right. Barney and Jan seemed almost as excited as I was about the prospect of The Who breaking big.

Peter Meaden also emphasised the importance of the Mod movement for us. That was the style and image he wanted us to embrace. Meaden was one of the authors and architects of the new vocabulary used by Mods, and I was eager to learn the lingo – beyond the little I’d learned when I was dating Carol Daltrey. Musically I felt I was already on course. Barney and Jan had both constantly urged me to develop my sound and guitar solos, and to utilise all the wildest, most pretentious ideas from our old Ealing art-school lectures.

John Entwistle, always uneasy with being merely a bass player, began to open up his sound as well. He already played louder than most other bass players, but now he began to play with more harmonics. When he later discovered wire-wound bass strings, his sound evolved into the one we recognise today, but even at this time his playing was expressive and creative, almost a second lead instrument. As I developed my sound, so did John, and it is now much clearer to the world what he did to advance the craft of electric bass guitar playing, especially in his development of special strings. We each occupied a specific part of the sonic spectrum, and although we occasionally attempted to dominate each other, the end result was that John’s sound perfectly complemented my own.

Against John’s loquacious bass lines and Keith’s liquid drumming I fell back further into using powerful, slab chords. My solos were often simply howling feedback, or stabbing noises, but never quite loud enough to suit me. One day in 1964 Jim Marshall delivered me an amplifier system I was reasonably happy with, a 45-watt amp that had a crisp American sound, but when you turned it up it screamed like a Spitfire, that essential British war machine – sleek, simple, undefeatable. I bought two, and used one to drive each of my speaker stacks of eight 12-inch speakers.

Now not only was my sound unique, it was so loud it shook most of the small halls in which we performed. Jim had no idea his amplifier design would make him rich, and I had no idea it would make me strong.

Despite my interest in songwriting, Peter Meaden decided he was going to write the two songs we would record for our first experience in a studio, the Fontana session. He had already persuaded us that The Who was a tacky, gimmicky name; it sounded uncool, so we were to record as The High Numbers. ‘Numbers’ was the term used for a Mod subgroup of lieutenants that rated below the fashion-leading ‘Faces’ (among whom Peter Meaden no doubt saw himself as a major player), but above the ‘Tickets’, the ordinary kids on the dance floor.

What was happening in the Mod movement was based on trendsetting fashion statements and dance moves by local Faces that were immediately copied by the rest of the kids in any particular locale. Meaden wanted to help that transmission along with coded messages in our songs. His idea fit so neatly into what I’d been taught at art college that I readily agreed to allow him to go ahead. We went to the home of Guy Stevens, a Face and the leading DJ at the exclusive Soho Scene Club, the most fashionable Mod stronghold in London. Guy lent Peter a couple of then rare R&B records that we all liked, and Peter borrowed liberally from them, replacing the lyrics with his own.

At the time we were getting most of our inspiration from growling R&B songs by Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf. Peter’s two songs were cool enough, but had very little of that driving R&B beat with its hard-edged guitar sound. Guitar feedback, a staple of our live shows, was entirely absent from the two sides Peter had written. On ‘Zoot Suit’, which was based on ‘Misery’ by The Dynamics, I play weedy jazz guitar, demonstrating that my solo work was undeveloped. The record didn’t break out, despite Peter Meaden’s assault on the pop magazines of the day. I think it sold about 400 copies. The problem was the sound, which was unoriginal. With Peter’s help we had developed an image, but the musical puzzle was still incomplete.

Looking back it seems astonishing to think that Peter Meaden, the principal articulator of the lifestyle that lay behind the emergent British Mod movement, missed out on the fact that we were breaking new ground with our sound. But he did. He hated all that feedback from my guitar, Keith battering away like a lunatic, Roger growling like an old black prisoner and John clanging at his bass sounding like Duane Eddy. It must have felt uncool to him. But when we played our first few shows in real Mod strongholds, like the Aquarium at Brighton, or The Scene Club, where pep pills and beautifully dressed young rent-boys were openly for sale, our Mod garb combined with that aggressive noise allied us to a very powerful new idea in pop culture: the elegant, disciplined, well-to-do, sharply dressed, dangerously androgynous yobbo.

What was I looking for in this drive to create a successful band? I was only eighteen and was motivated by artistic visions as well as the usual pop-star dreams: money, fame, a big car and a gorgeous girlfriend. We had just made our first record for a major label, and I had had sex for the first time not long before. To me the sexual conquests of Roger, John and Keith were as fantastical and unapproachable as my theories of auto-destruction were to them. Barney and Jan sometimes emerged from Barney’s bedroom to join me for our ritual brainstorm chats after they’d conducted a long and sweaty sex session I could only imagine. How could it all last over an hour?

Of course I was dealing with psychological issues that my closest friends and bandmates didn’t share. I suffered from a deep sexual shame over my dealings with Denny, although I’d managed to push the details out of memory’s reach. Why should a victim of childhood abuse feel sexual shame at all? I still have no answer to this question, but its roots may lie in our tendency as children to take the blame. Perhaps it’s a way of pretending we have some degree of control over our lives, when to acknowledge the alternative might drive us insane.

At the time I didn’t realise how many other people were working through similar feelings. So many children had lived through terrible trauma in the immediate postwar years in Britain that it was quite common to come across deeply confused young people. Shame led to secrecy; secrecy led to alienation. For me these feelings coalesced in a conviction that the collateral damage done to all of us who had grown up amid the aftermath of war had to be confronted and expressed in all popular art – not just literature, poetry or Picasso’s Guernica. Music too. All good art cannot help but confront denial on its way to the truth.

With The Who I felt I had a chance to make music that would become a part of people’s lives. Even more than the way we dressed, our music would give voice to what we all needed to express – as a group, as a gang, as a fellowship, as a secret society, as subversives. I saw pop artists as mirrors of their audience, developing ways to reflect and speak truth without fear.

Still, I was more certain then of the medium than the message. Surely, God help us all, we weren’t just going to write songs about falling in love, or hopeless longing? What was it, then, that needed to be said?

I had found a new sound. Now I needed the words.

In a remarkable act of synchronicity, two young men, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, had been searching London in order to make a film about some wonderful new, as yet undiscovered band that came from the street. Kit saw us perform that first time at the Railway Hotel in July when I smashed my guitar and described us as satanic. He persuaded Chris to come and see us, and they quickly decided to make us the subject of their film.

The two friends (later dubbed by the media ‘the fifth and sixth members of The Who’) came from very different backgrounds. Chris, from the East End of London, was the son of a Thames waterman; Kit was the son of Constant Lambert, the musical director of the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. Chris was drop-dead handsome, even better looking than his famous film-star brother, Terence. Kit had a look of Brian Epstein about him; we all thought he was gay. Most importantly, the two of them knew how to get things done.

Kit and Chris made their film. (That film still exists; Roger now owns the only remaining copy.) Then they decided to go one better, and offered to manage us. But Peter Meaden and Helmut Gorden didn’t want to give us up. At some point in the negotiations Meaden brought the manager of the Stones, Andrew Oldham, to see us play at a rehearsal hall in Shepherd’s Bush. He liked us, but when Kit’s name was mentioned it quickly became clear that Oldham already knew Kit (they were neighbours), and Oldham wasn’t going to get embroiled in Peter Meaden’s failing power struggle.

Kit and Chris later confronted Meaden at a band rehearsal – an occasion on which Phil the Greek, Meaden’s henchman, flashed a knife and menaced Kit. But Peter Meaden eventually stood aside for the then princely sum of £200, and Kit and Chris took over the management of the band. They quickly gave us back our proper name – The Who.

We had begun to play on regular summer Sunday concert bills with established major artists, all of whom had chart hits at the time. We supported The Beatles, The Kinks, Dusty Springfield, the extraordinary Dave Berry and Lulu. The Beatles’ audience was almost entirely young girls who seemed lost in their own fantasy world while the music played. (The theatre really did smell of urine after the show.) Unlike the Stones, The Beatles seemed almost like royalty, distant and caught up in their own extraordinary potency. After they had been whisked away after their show, we hung around, and Kit was mobbed by girls who thought he was The Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein.

Lulu was just fifteen when we played with her in Glasgow, after which we attended her sixteenth birthday party. She had an enormous, soulful voice, and while the accordion played I nearly got off with her best friend. Dave Berry’s hit was ‘The Crying Game’, and his act was the antithesis of the others. He moved slowly, with measured, controlled movements, almost like a mime artist, but he too drove the girls wild.

Away from the big-city Mod strongholds, these shows were like mini-festivals of bands with recent or current hits. We were all young, but there was solidarity between us reminiscent of the show business of Dad’s generation. We learned from everyone we performed with, secure in the knowledge that none of them would borrow too much from us: our whining guitars and auto-destruction were our own inviolate territory.

At last we seemed to be achieving something, but it was proving a much slower, harder grind than promised in the heady days when Peter Meaden was telling us we’d be huge overnight. We passed one BBC radio audition but failed another, and also failed an audition for a recording contract with EMI. Our heavy-handed style confused a lot of older people, including record executives, and we mainly played covers of R&B material. The record labels wanted bands that wrote their own songs.

The Who kept working, trying and failing to get a guitar-smashing moment into the national newspapers. The Decca Records audition was our most encouraging. Kit’s friend Russ Conway, the popular boogie-woogie TV pianist and principal investor in Kit and Chris’s management company, arranged the audition and persuaded A&R man John Burgess to take us seriously. Kit and Chris later confided that we would have passed the audition had we played original compositions. Knowing I could write songs, they encouraged me to come up with some new material that might suit the band.

This was the most critical challenge I had ever faced. I isolated myself in the kitchen of the flat in Ealing where I kept my tape machine, listening to a few records over and over again: Bob Dylan’s Freewheelin’; Charlie Mingus’s ‘Better Get It in Your Soul’ from Mingus Ah Um (I loved Mingus and was obsessed with Charlie Parker and Bebop); John Lee Hooker’s ‘Devil’s Jump’; and ‘Green Onions’ (although my record was nearly worn out). I tried to divine what it was I was actually feeling as a result of this musical immersion. One notion kept coming into my head: I can’t explain. I can’t explain. This would be the title of my second song, and I was already doing something I would often do in the future: writing songs about music.

Got a feeling inside, I can’t explain

A certain kind, I can’t explain

Feel hot and cold, I can’t explain

Down in my soul, I can’t explain

At the time I was still using a clunky old domestic tape recorder to record my songs, which I used to put down a simple demo. Barney listened to it when he got home from college and liked it. I remember him describing it as Bob Dylan with a hint of Mose Allison.

Kit and Chris, through a friend of their glamorous personal assistant, Anya Butler, met with the producer of The Kinks’ recent chart hits, Shel Talmy, who had his own label deal with Decca in the USA. He agreed to hear us.

I ran back to my tape machine and listened to The Kinks’ ‘You Really Got Me’ – not that I really needed to, it was on the radio all the time. I tightened up ‘I Can’t Explain’ and changed the lyrics so they were about love, not music. I tried to make it sound as much like The Kinks as I could so that Shel would like it. I already had the title for the song that would follow it: ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere’, words I had scribbled on a piece of paper while listening to Charlie Parker.

We played Shel Talmy the revised ‘I Can’t Explain’ and he booked us a session at Pye studios to record it. Shel also brought in some additional musicians, which Kit had warned me he might do. Keith jovially told the session drummer who appeared to ‘scarper’, and he did. Because Shel wasn’t sure I could play a solo, he had asked his favorite session guitarist, Jimmy Page, to sit in. And because our band had rehearsed the song with backing vocals in Beach Boys style, but not very skilfully, Shel arranged for three male session singers, The Ivy League, to chirp away in our place.

Shel Talmy got a good sound, tight and commercial, and although there was no guitar feedback I was willing to compromise to get a hit. We wouldn’t know if the gamble would pay off until after the New Year.

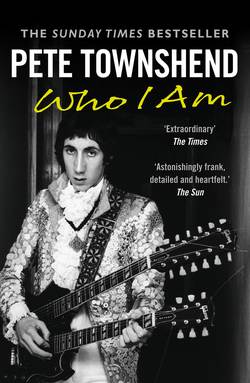

In November, Kit and Chris secured us a residency on Tuesday nights at the Marquee Club, a jazz and blues venue in Soho, and mounted an inspired campaign to make sure our first evening didn’t fail. In one of my art notebooks Kit and Chris found some doodling they liked for a Who logo, incorporating the Mars symbol I’d used in my design for The Detours van years before. We had already done a number of photo sessions for various magazines, but Kit and Chris organised their own, and the photographer took a solo picture of me swinging my arm.

A graphic designer friend from Ealing made the ‘Maximum R&B’ poster now legendary in collectable Who paraphernalia, and Kit and Chris had it plastered all over central London. They went further: along with a general card for hand-out, they printed up 150 special invitations to join ‘The 100 Faces’, an elite hand-picked group of Mods, with free entry to the first few weeks of our residency. Again, for some reason, only my face was featured, not one of our prettier boys.

Kit hired Chris’s school friend Mike Shaw to act as our production manager. He became the only person ever to pass through The Who camp that no one will ever say a bad word about. He was a joy. He ran around all our gigs finding the coolest-looking Mod boys and handing them cards. Our attendance was about 90 per cent male, but a few girls were in the front row at the Marquee in the early days. Attendance started slowly, but built up very quickly to a packed house.

That winter playing our regular gig at the Marquee became an event I looked forward to. I remember wearing a chamois jacket, carrying a Rickenbacker guitar, coming up from the bowels of the earth at Piccadilly Circus train station feeling as though there was nothing else I’d rather be doing. I was an R&B musician with a date to play. It was a great adventure, and I was full of ideas. In my notebooks I was designing Pop Art T-shirts, using medals and chevrons and the Union Flag to decorate jackets I intended to wear. At the Marquee I felt, like many in our audience, that Mod had become more than a look. It had become a voice, and The Who was its main outlet.

A magazine photographer visiting our flat one day for a shoot had to climb up a stepladder to get his equipment out of the knee-deep rubbish that filled the room, trash now invisible to Barney and me. After the photo was taken Kit quietly took me aside and explained that he and Chris had obtained a very smart residence and office in Eaton Place in Belgravia, and felt I should move there. I worried a little that I might appear to be moving in to sleep with Kit, but the next morning I said goodbye to a stunned Barney and moved into the exquisitely tidy bedroom – adjacent through glass doors to Kit’s – in a high-ceiling first-floor flat in a Georgian building in what is still the poshest street in London. I taped up some nifty Pop Art images cut from magazines, set up a record player and lived like a prince.

Chris, it emerged, didn’t have a bedroom in the flat, and Kit never attempted to seduce me, to my disappointment, although I probably wouldn’t have responded. Happily, though, Anya did seduce me. I was 19, she was 30, and the sex was gloriously educational. While sending me into ecstasy with her long, sharp fingernails, she told me she had spurned the advances of all three other members of the band.

Kit and Chris asked their friend Jane, wife of Kit’s old army friend Robert Fearnley-Whittingstall, to run a fan club for us. She became known as ‘Jane Who’, collected letters for us and kept a mailing list. Jane gave mail addressed to me unopened, and thinking that one day I might write this book I decided to leave one of those letters sealed until the day I finished it.1

For a time I lived under Kit’s nose quite blissfully. I felt completely safe, protected, adored, cherished and valued, although I was still smoking a lot of grass, which I think Kit disapproved of. One evening I decided to conduct an experiment. Instead of my usual ritual of listening to music stoned, I began to listen to some of my choicest records while drinking good Scotch whisky. As I listened and drank, I wrote down what was going on in my head:

I begin to feel afraid. Childhood self-pity arises. Music is inside me. Am not afraid to let it in. Finding new perceptive levels. I’m underwater, not going too deep. Going to write with eyes closed. Swimming with the fish. Unexplainable emotion now. Death.

My demons were still with me, but I was learning how to use them to fuel my creative process.

1 See Appendix