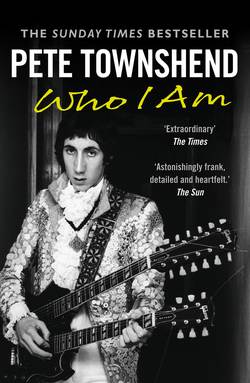

Читать книгу Pete Townshend: Who I Am - Pete Townshend - Страница 5

Оглавление1 I WAS THERE

It’s extraordinary, magical, surreal, watching them all dance to my feedback guitar solos; in the audience my art-school chums stand straight-backed among the slouching West and North London Mods, that army of teenagers who have arrived astride their fabulous scooters in short hair and good shoes, hopped up on pills. I can’t speak for what’s in the heads of my fellow bandmates, Roger Daltrey, Keith Moon or John Entwistle. Usually I’d be feeling like a loner, even in the middle of the band, but tonight, in June 1964, at The Who’s first show at the Railway Hotel in Harrow, West London, I am invincible.

We’re playing R&B: ‘Smokestack Lightning’, ‘I’m a Man’, ‘Road Runner’ and other heavy classics. I scrape the howling Rickenbacker guitar up and down my microphone stand, then flip the special switch I recently fitted so the guitar sputters and sprays the front row with bullets of sound. I violently thrust my guitar into the air – and feel a terrible shudder as the sound goes from a roar to a rattling growl; I look up to see my guitar’s broken head as I pull it away from the hole I’ve punched in the low ceiling.

It is at this moment that I make a split-second decision – and in a mad frenzy I thrust the damaged guitar up into the ceiling over and over again. What had been a clean break becomes a splintered mess. I hold the guitar up to the crowd triumphantly. I haven’t smashed it: I’ve sculpted it for them. I throw the shattered guitar carelessly to the ground, pick up my brand-new Rickenbacker twelve-string and continue the show.

That Tuesday night I stumbled upon something more powerful than words, far more emotive than my white-boy attempts to play the blues. And in response I received the full-throated salute of the crowd. A week or so later, at the same venue, I ran out of guitars and toppled the stack of Marshall amplifiers. Not one to be upstaged, our drummer Keith Moon joined in by kicking over his drumkit. Roger started to scrape his microphone on Keith’s cracked cymbals. Some people viewed the destruction as a gimmick, but I knew the world was changing, and a message was being conveyed. The old, conventional way of making music would never be the same.

I had no idea what the first smashing of my guitar would lead to, but I had a good idea where it all came from. As the son of a clarinettist and saxophonist in the Squadronaires, the prototypical British Swing band, I had been nourished by my love for that music, a love I would betray for a new passion: rock ’n’ roll, the music that came to destroy it.

I am British. I am a Londoner. I was born in West London just as the devastating Second World War came to a close. As a working artist I have been significantly shaped by these three facts, just as the lives of my grandparents and parents were shaped by the darkness of war. I was brought up in a period when war still cast shadows, though in my life the weather changed so rapidly it was impossible to know what was in store. War had been a real threat or a fact for three generations of my family.

In 1945 popular music had a serious purpose: to defy postwar depression and revitalise the romantic and hopeful aspirations of an exhausted people. My infancy was steeped in awareness of the mystery and romance of my father’s music, which was so important to him and Mum that it seemed the centre of the universe. There was laughter and optimism; the war was over. The music Dad played was called Swing. It was what people wanted to hear. I was there.