Читать книгу The Curious Charms Of Arthur Pepper - Phaedra Patrick - Страница 10

The Great Escape

ОглавлениеIt was still dark the next morning when Arthur woke. The digits on his alarm clock flicked to 5:32 a.m. and he lay for a while staring at the ceiling. Outside a car drove past and he watched the reflection of the headlights sweep over the ceiling like the rays of a lighthouse across water. He let his fingers creep across the mattress, reaching out for Miriam’s hand knowing it wasn’t there and feeling only cool cotton sheet.

Each night, when he went to bed, it struck him how chilly it was without her. When she was next to him he always slept through the night, gently drifting off, then waking to the sound of thrushes singing outside. She would shake her head and ask did he not hear the thunderstorm or next door’s house alarm going off? But he never did.

Now his sleep was fitful, restless. He woke up often, shivering and wrapping the duvet around him in a cocoon. He should put an extra blanket on the bed, to stop the cold from creeping around his back and numbing his feet. His body had found its own strange rhythm of sleeping, waking, shivering, sleeping, waking, shivering, which, although uncomfortable, he didn’t want to shake. He didn’t want to drop off and then wake with the birds and find that Miriam was no longer there. Even now that would be too much of a shock. Stirring through the night reminded him that she had gone and he welcomed those constant reminders. He didn’t want to risk forgetting her.

If he had to describe in one word how he felt this morning, it would be perplexed. Getting rid of Miriam’s clothes was going to be a ritual, freeing the house of her things, her shoes, her toiletries. It was a small step in coping with his loss and moving on.

But the newly-discovered charm bracelet was an obstacle to his intentions. It raised questions where once there were none. It had opened a door and he had stepped through it.

He and Miriam differed in how they saw mysteries. They regularly enjoyed a Miss Marple or a Hercule Poirot on a Sunday afternoon. Arthur would watch intently. ‘Do you think it’s him?’ he would say. ‘He’s being very helpful and his character adds nothing to the story. I think he might be the killer.’

‘Watch the film.’ Miriam would squeeze his knee. ‘Just enjoy it. You don’t have to psychoanalyse all the characters. You don’t have to guess the ending.’

‘But, it’s a mystery. It’s supposed to make you guess. We’re supposed to try and work it out.’

Miriam would laugh and shake her head.

If this were the other way round and (he hated to think this) he had died, Miriam might not have given finding a strange object in Arthur’s wardrobe much thought. Whereas here he was, his brain whirring like a child’s windmill in the garden.

He creaked out of bed and took a shower, letting the hot water bounce off his face. Then he dried himself off, had a shave, put on his grey trousers, blue shirt and mustard tank top and headed downstairs. Miriam liked it when he wore these clothes. She said they made him look presentable.

For the first weeks after she died, he couldn’t even be bothered getting dressed. Who was there to make an effort for? With his wife and children gone, why should he care? He wore his pyjamas day and night. For the first time in his life he grew a beard. When he saw himself in the bathroom mirror he was surprised at his resemblance to Captain Birdseye. He shaved it off.

He left radios on in each room so he wouldn’t have to hear his own footsteps. He survived on yoghurts and cans of soup, which he didn’t bother to heat. A spoon and a can opener were all he needed. He found himself small jobs to do: tightening the bolts on the bed to stop it squeaking, scratching out the blackened grout around the bath.

Miriam kept a fern on the windowsill in the kitchen. It was a moth-eaten thing with drooping feathery leaves. He despised it at first, resenting how such a pathetic thing could live when his wife had died. It had sat on the floor by the back door waiting for bin day. But, out of guilt, he relented and set it back in its place. He named it Frederica and began to water and talk to it. And slowly she perked up. She no longer drooped. Her leaves grew greener. It felt good to nurture something. He found it easier to chat to the plant than to people. It was good for him to keep busy. It meant he didn’t have time to be sad.

Well, that’s what he told himself, anyway. But then he’d be going about his daily tasks, kind of doing okay, holding it together. Then he’d spy the green pot pourri fabric leaf hanging in the hallway or Miriam’s mud-encrusted walking shoes in the pantry, or the lavender Crabtree & Evelyn hand cream on the shelf in the bathroom—and it would feel like a landslide. Such small meaningless items now tore at his heart.

He would sit on the bottom step of the stairs and hold his head in his hands. Rocking backward and forward, squeezing his eyes shut, he told himself that he was bound to feel like this. His grief was still raw. It would pass. She was in a better place. She wouldn’t want him to be like this. Blah blah. All the usual mumbo-jumbo from Bernadette’s leaflets. And it did pass. But it never vanished completely. He carried his loss around with him like a bowling ball in the pit of his stomach.

At these times he imagined his own father, stern, strong: ‘Bloody ‘ell. Pull yerself together, lad. Crying’s for sissies,’ and he would lift his chin and try to be brave.

Perhaps he should be getting over it by now.

His recollections of those dark early days were foggy. What he did recall was like seeing it on a black-and-white TV set with a crackly picture. He saw himself shuffling around the house.

If he was honest, then Bernadette had been a great help.

She had turned up on his doorstep like an unwelcome genie and insisted that he bathed while she cooked lunch. Arthur hadn’t wanted to eat. Food held no taste or pleasure for him.

‘Your body is like a steam train that needs coal,’ Bernadette said as he protested against the pies, soups and stews she carried over his threshold, heated and then placed in front of him. ‘How are you going to carry on your journey without fuel?’

Arthur wasn’t planning any journey. He didn’t want to leave the house. The only trip he made was upstairs to use the bathroom or go to bed. He had no desire to do anything more than that. For a quiet life he ate her food, blocked out her chatter, read her leaflets. He really would prefer to be left alone.

But she persisted. Sometimes he answered the door to her, other times he wriggled down in the bed and pulled the blankets over his head or thrust himself into National Trust statue mode. But she never gave up on him.

Later that morning, as if she knew he was thinking of her, Bernadette rang his doorbell. Arthur stood in the dining room, still for a few moments, wondering whether to go to the door. The air smelled of bacon and eggs and fresh toast as the other residents of Bank Avenue enjoyed their breakfasts. The doorbell rang again.

‘Her husband Carl died recently,’ Miriam had told him, a few years ago, as she spied Bernadette on a stall at a local church fete, selling butterfly buns and chocolate cake. ‘I think that bereaved people act in one of two ways. There are those who cling with their fingertips to the past, and those who brush their hands together and get on with their lives. That lady with the red hair is the latter. She keeps herself busy.’

‘Do you know her?’

‘She works at LadyBLovely, the boutique in the village. I bought a navy dress from there. It has tiny pearl buttons. She told me that, in her husband’s memory, she was going to help others through her baking. She said that if people are tired, lonely, heartbroken, or have simply run out of steam, then they need food. I think it’s very courageous of her to make it her mission to help others.’

From then on Arthur noticed Bernadette more—at the local school summer fair, in the post office, in her dressing gown tending roses in her garden. They said hello to each other and not much else. Sometimes he saw Bernadette and Miriam chatting on the street corner. They would laugh and talk about the weather and how strawberries were sweet this year. Bernadette’s voice was so loud that he could hear the conversation from inside the house.

Bernadette had attended Miriam’s funeral. He had a hazy memory of her appearing beside him and patting his arm. ‘If you ever need anything, just ask,’ she said and Arthur wondered what he might possibly ever ask her for. Then she had started to turn up announced on his doorstep.

At first he felt irritated by her presence, then he began to worry that she had set her sights on him, perhaps as a potential second husband. He wasn’t looking for anything like that. He never could do after Miriam. But in all the months she had been knocking on his door, Bernadette hadn’t ever given him cause to think her attention was anything more than platonic. She had a full roster of widows and widowers to call upon.

‘Mince and onion pie,’ she greeted him as he opened up. ‘Freshly made.’ She let herself into the hallway, pie-first. There, she ran her finger along the shelf over the radiator and nodded with satisfaction that it was dust free. She sniffed the air. ‘It’s a bit musty in here. Do you have air freshener?’

Arthur marvelled at how impolite she could be without realising and dutifully fetched one. A few seconds later and the cloying smell of Mountain Lavender filled the air.

She bustled into the kitchen and put the pie down on the worktop. ‘This is a mighty fine kitchen,’ she said.

‘I know.’

‘The cooker is wondrous.’

‘I know.’

Bernadette was the polar opposite to Miriam. His wife had sparrow bones. Bernadette was fleshy, cushioned. Her hair was dyed post-box red and she wore diamanté studs on the tips of her nails. One of her front teeth was stained yellow. Her voice was big, cutting through the quiet of his home like a machete. He jangled the bracelet nervously in his pocket. Since speaking to Mr Mehra last night, he had kept it with him. He had studied each charm in turn several times.

India. It was so far away. It must have been such an adventure for Miriam. Why had she not wanted him to know? Surely Mr Mehra’s story wasn’t enough for her to keep it secret.

‘Are you okay, Arthur? You’re in a dream world.’ Bernadette’s words broke his thoughts.

‘Me? Yes, of course.’

‘I called yesterday morning but you weren’t in. Did you go to Men in Caves?’

Men in Caves was a community group for single men. Arthur had been twice to find a group of men with gloomy expressions handling chunks of wood and tools. The man who ran it, Bobby, was shaped like a skittle with a tiny head and large body. ‘Men need caves,’ he trilled. ‘They need somewhere to retreat to and be at one with themselves.’

Arthur’s neighbour with the dreadlocks had been there. Terry. He was busy filing a piece of wood. ‘I like your car,’ Arthur said to be polite.

‘It’s actually a tortoise.’

‘Oh.’

‘I saw one last week when I was mowing my lawn.’

‘A wild one?’

‘It belongs to the red-haired kids who wear nothing on their feet. It escaped.’

Arthur didn’t know what to say. He had enough trouble with cats on his rockery without a tortoise being on the loose too. Returning to his own work, he made a wooden plaque with the number of his house on it—37. The 3 was much bigger than the 7 but he hung it on his back door anyway.

It would have been easy to say yes, he was at Men in Caves, even though it had been too early in the morning. But Bernadette was standing and smiling at him. The pie smelled delicious. He didn’t want to lie to her, especially after hearing Mr Mehra’s regret over telling lies about Miriam. He would do the same and try not to lie again. ‘I hid from you yesterday,’ he said.

‘You hid?’

‘I didn’t want to see anyone. I’d set myself the task to clear out Miriam’s wardrobe and so when you rang the doorbell, I stood very still in the hallway and pretended not to be at home.’ The words tumbled off his tongue and it felt surprisingly good to be this honest. ‘Yesterday was the first anniversary of her death.’

‘That’s very truthful of you, Arthur. I appreciate your honesty. I can see how that would be upsetting. When Carl died … well, it was a hard thing to let him go. I gave his tools to Men in Caves.’

Arthur felt his heart dip. He hoped that she wouldn’t tell him about her husband. He didn’t want to trade stories of death. There seemed to be a strange one-upmanship amongst people who had lost spouses. Only last week in the post office he had witnessed what he would describe as boasting amongst a group of four pensioners.

—‘My wife suffered for ten years before she eventually passed away.’

—‘Really? Well, my Cedric was flattened by a lorry. The paramedics said they’d never seen anything like it. Like a pancake, one said.’

—Then a man’s voice, breaking. ‘It was the drugs, I reckon. Twenty-three tablets a day they gave her. She almost rattled.’

—‘When they cut him open there was nothing left inside. The cancer had eaten him all up.’

They talked about their loved ones as if they were objects. Miriam would always be a real person to him. He wouldn’t trade her memory like that.

‘She likes lost causes,’ Vera, the post office mistress, said to him as he took a pack of small brown manila envelopes to the counter. She always wore a pencil tucked into her round tortoiseshell glasses and made it her business to know everything and everyone in the village. Her mother had owned the post office before her and had been exactly the same.

‘Who does?’

‘Bernadette Patterson. We’ve noticed that she brings you pies.’

‘Who has noticed?’ Arthur said, feeling angry. ‘Is there a club whose role it is to pry into my life?’

‘No, just my customers having a friendly information exchange. That’s what Bernadette does. She’s kind to the hopeless, helpless and useless.’

Arthur paid for his envelopes and marched out.

He stood and switched on the kettle. ‘I’m giving Miriam’s things to Cat Saviours. They sell clothes, ornaments and things to raise money to help mistreated cats.’

‘That’s a nice idea, though I prefer small dogs myself. They’re much more appreciative.’

‘I think Miriam wanted to help cats.’

‘Then that’s what you must do. Shall I pop this pie in the oven for you? We can have lunch together. Unless you have other plans …’

He was about to murmur something about being busy but then remembered Mr Mehra’s story again. He had no plans. ‘No, nothing in the diary,’ he said.

Twenty minutes later as he dug his knife into the pie, he thought about the bracelet again. Bernadette could give him a woman’s perspective. He wanted someone to tell him that it was of no significance and that, although it looked expensive, you could buy good reproductions cheaply these days. But he knew the emerald in the elephant was real. And she might gossip about it to Post Office Vera and to her lost causes.

‘You should get out more,’ she said. ‘You only went to Men in Caves once.’

‘I went twice. I do get out.’

She raised an eyebrow. ‘Like to where?’

‘Is this Mastermind? I don’t remember applying.’

‘I’m just trying to take care of you.’

She saw him as a lost cause, just as Vera had implied.

He didn’t want to feel like this, be treated like this. An urge swelled in his chest. He needed to say something so she wouldn’t think him helpless, hopeless and useless, like Mrs Monton who hadn’t left her house in five years and who smoked twenty Woodbines a day, or Mr Flowers who thought there was a unicorn living in his greenhouse. Arthur had some pride left. He used to have meaning as a father and a husband. He used to have thoughts and dreams and plans.

Thinking of the forwarding address Miriam had left on her letter to Mr Mehra, he cleared his throat. ‘Well, if you must know,’ he said hurriedly, ‘I’ve been thinking about going to Graystock Manor in Bath.’

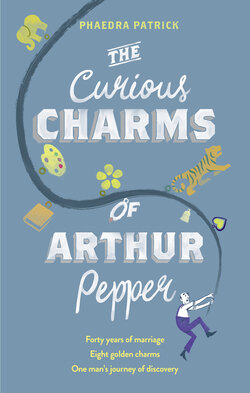

‘Oh yes,’ Bernadette mused. ‘That’s where the tigers roam free.’

Bernadette was a one-woman almanac of the UK. She and Carl had toured everywhere together in their luxury campervan. The back of Arthur’s neck bristled as he prepared to hear where he should and shouldn’t go, what he should and shouldn’t do, at Graystock.

As she busied herself in his kitchen, straightening his scales and checking that his knives were clean enough, Bernadette recited what she knew.

No, Arthur didn’t know that five years ago Lord Graystock had been mauled by a tiger, which sank its teeth and claws into his calf, and now he walked with a limp. He also didn’t know that, as a younger man, Graystock kept a harem of women of all nationalities, like a hedonistic Noah’s ark, or that he was renowned for hosting wild orgies at his manor in the sixties. He also didn’t know that the lord only wore the colour electric blue, even his underwear, because he had once been told in a dream that it was lucky. (Arthur wondered if he had been wearing electric blue during the tiger attack.)

He also now knew that Lord Graystock tried to sell his manor to Richard Branson; however the two men had fallen out and refused to speak to each other ever again. The lord was now a recluse and only opened up Graystock Manor on Fridays and Saturdays and the public were no longer allowed to look at the tigers.

After Bernadette’s tales, Arthur now felt well informed about Lord Graystock’s life and times.

‘It’s just the gift shop and gardens that are open now. And they’re a bit tatty.’ Bernadette finished cleaning Arthur’s mixer taps with a flourish. ‘Why are you going there?’

Arthur looked at his watch. He wished he hadn’t said anything now. She had taken twenty-five minutes to regale him. His left leg had grown stiff. ‘I thought it would be a nice change,’ he said.

‘Well, actually, Nathan and I are going to be down in Worcester and Cheltenham next week. We’re looking at universities. Tag along if you like. You could head off to Graystock on the train from there.’

Arthur’s stomach felt fizzy. Going to Graystock had only been a mild consideration for him. He hadn’t actually planned to go there. He only went on outings with Miriam. What was the point of going alone? He had only mentioned going to Graystock to show Bernadette that he wasn’t useless. Now apprehension nagged him. He wished he could turn back the clock and not have pushed his hand into the boot and discovered the bracelet. Then he would never have phoned the number on the elephant. He wouldn’t be sitting here discussing Graystock Manor with Bernadette. ‘I’m not sure about it,’ he said. ‘Another time perhaps …’

‘You should go. Try to move on with your life. Small steps. An outing might do you good.’

Arthur was surprised to feel a tiny kernel of excitement taking root in his stomach. He had found out something about his wife’s past life and his inquisitive nature was compelling him to find out more. The only feelings he experienced these days were sadness, disappointment and melancholy, so this felt new. ‘I like the idea of tigers walking around an English garden,’ he said.

And he did like tigers. They were strong majestic colourful beasts, prowling around with the key purposes in life of hunting, eating and mating. Humans were so different with their lives of meekness and worry.

‘Really? I’d have you down more as a small dog person, you know a terrier or something. Or you look like the kind of person who would like hamsters. Anyway, why don’t you come with us in the car? Nathan is driving.’

‘Are you not taking the campervan?’

‘I’m selling it. It’s too big for me to handle and I’ve been paying for storage since Carl died. Nathan’s got a Fiesta. It’s a rust bucket but reliable.’

‘Shouldn’t you ask him first? He might have other plans …’ Arthur instinctively found himself trying to get out of the trip. He should have kept his mouth shut. He couldn’t carry out his daily chores if he went away. His timings would be up the shoot. Who would care for Frederica the fern and stop the cats crapping in his garden? If he went down south then he might have to stay overnight. He had never packed his own suitcase before. Miriam did that kind of thing for him … His brain ticked away trying to find excuses. He didn’t want to pry on his wife but he did want to discover more about her life before they met.

‘No, no. Nathan doesn’t really do thinking. I do it all for him. It will do him good to have some self-responsibility. He won’t have remembered that he has to look at universities. I know he won’t need to apply for a few months but I want to start early. I will be so lonely when he goes. It will be strange being on my own again. I dread to think how he’ll cope away from me. I’ll visit him in his student digs and find his skeleton because he’s forgotten to eat …’

Arthur had been about to say that, now he thought about it, he might go later in the year. He already knew that he didn’t want to go on a trip with Bernadette and her son. He had met Nathan briefly once before when he and Miriam had bumped into Bernadette at a coffee morning. He seemed like a monosyllabic kind of young man. Arthur really didn’t want to leave the security of his house, the smothering comfort of his routine.

But then Bernadette said, ‘When Nathan leaves, I will be all on my own. A lonely widow. Still, at least I have you and my other friends, Arthur. You’re like family to me.’

Guilt twisted his gut. She sounded lonely. It was a word he would never have used to describe her. Every cautious nerve in his body told him not to go to Graystock. But he wondered what connection Miriam had there. It seemed a highly unlikely address for her. But then so was India. Lord Graystock sounded an intriguing character and his family had owned the manor for years, so there was a possibility that he might know or remember Miriam. He might know the stories behind more of the charms. Could Arthur really expect to be able to forget all about the charm bracelet, to put it back in its box and not discover more about his wife as a young woman?

‘Do you mind if I’m honest with you?’ Bernadette said. She sat down beside him and wrung a tea towel in her hands.

‘Er, no …’

‘It’s been difficult for Nathan since Carl died. He doesn’t say much but I can tell. It would be good for him to have a little male company. He has his friends but, well, it’s not the same. If you could give him a bit of advice or guidance while we’re travelling … I think that would do him good.’

It took all his might for Arthur not to shake his head. He thought about Nathan with his runner-bean body and black hair that hung over one eye like a mortuary curtain. When they met, the boy had hardly spoken over his coffee and cake. Now Bernadette was expecting Arthur to have a man-to-man talk with him. ‘Oh, he won’t listen to me,’ he said lightly. ‘We’ve only met the once.’

‘I think he would. All he hears is me telling him what and what not to do. I think it would do him the world of good.’

Arthur took a good look at Bernadette. He usually averted his eyes, but this time he took in her scarlet hair: her dark grey roots were springing through. The corners of her mouth drooped downwards. She really wanted him to say yes.

He could take Miriam’s things to the charity shop. He could put the bracelet back in his wardrobe and forget about it. That would be the easy option. But there were two things stopping him. One, was the mystery of it. Like one of the Sunday afternoon detective stories that he and Miriam watched, finding the stories behind the charms on the bracelet would nag at his brain. He could find out more about his wife and feel close to her. And the second was Bernadette. In the many times she had called around with her pies and kind words, she had never once asked for anything in return—not money, not a favour, not to listen to her talk about Carl. But now she was asking him for something.

He knew that she would never insist, but he could tell by the way she sat before him, turning her wedding ring around and around on her finger, that this was important to her. She wanted Arthur to accompany her and Nathan on their trip. She needed him.

He rocked a little in his chair, telling himself that he had to do this. He had to silence the nagging voices in his head telling him not to go. ‘I think a trip to Graystock would do me good,’ he said before he could change his mind. ‘And I think me and Nathan will get along just swell. Count me in.’