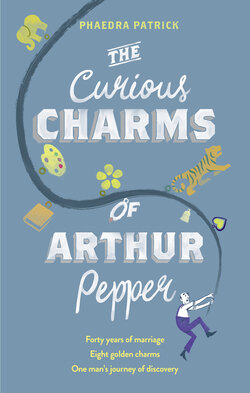

Читать книгу The Curious Charms Of Arthur Pepper - Phaedra Patrick - Страница 8

The Surprise in the Wardrobe

ОглавлениеEach day, Arthur got out of bed at precisely 7:30 a.m. just as he did when his wife, Miriam, was alive. He showered and got dressed in the grey slacks, pale blue shirt and mustard tank top that he had laid out the night before. He had a shave then went downstairs.

At eight o’clock he made his breakfast, usually a slice of toast and margarine, and he sat at the pine farmhouse table that could seat six, but which now just seated one. At eight-thirty he would rinse his pots and wipe down the kitchen worktop using the flat of his hand and then two lemon-scented Flash wipes. Then his day could begin.

On an alternative sunny morning in May, he might have felt glad that the sun was already out. He could spend time in the garden plucking up weeds and turning over soil. The sun would warm the back of his neck and kiss his scalp until it was pink and tingly. It would remind him that he was here and alive—still plodding on.

But today, the fifteenth day of the month, was different. It was the anniversary he had been dreading for weeks. The date on his Stunning Scarborough calendar caught his eye whenever he passed it. He would stare at it for a moment then try to find a small job to distract him. He would water his fern, Frederica, or open the kitchen window and shout ‘Gerroff’ to deter next door’s cats from using his rockery as a toilet.

It was one year to the day that his wife had died.

Passed away was the term that everyone liked to use. It was as if saying the word died was swearing. Arthur hated the words passed away. They sounded gentle, like a canal boat chugging through rippling water, or a bubble floating in a cloudless sky. But her death hadn’t been like that.

After over forty years of marriage it was just him in the house now, with its three bedrooms and the en-suite shower room that grown-up daughter, Lucy, and son, Dan, recommended they had fitted with their pension money. The recently installed kitchen was made from real beech and had a cooker with controls like the NASA space centre, and which Arthur never used in case the house lifted off like a rocket.

How he missed the laughter in the home. He longed to hear again the pounding of feet on the stairs, and even doors slamming. He wanted to find stray piles of washing on the landing and trip over muddy wellies in the hallway. Wellibobs the kids used to call them. The quietness of it being just him was more deafening than any family noise he used to grumble about.

Arthur had just cleaned his worktop and was heading for his front room when a loud noise pierced his skull. He instinctively pressed his back against the wall. His fingers spread out against magnolia woodchip. Sweat prickled his underarms. Through the daisy-patterned glass of his front door, he saw a large purple shape looming. He was a prisoner in his own hallway.

The doorbell rang again. It was amazing how loud she could make it sound. Like a fire bell. His shoulders shot up to protect his ears and his heart raced. Just a few more seconds and surely she’d get fed up and leave. But then the letterbox opened.

‘Arthur Pepper. Open up. I know you’re in there.’

It was the third time this week that his neighbour Bernadette had called around. For the past few months she had been trying to feed him up with her pork pies or home-made mince and onion. Sometimes he gave in and opened the door; most of the time he did not.

Last week he had found a sausage roll in his hallway, peeking out of its paper bag like a frightened animal. It had taken him ages to clear up the flakes of pastry from his hessian welcome mat.

He had to hold his nerve. If he moved now she would know he was hiding. Then he’d have to think of an excuse; he was putting out the bins, or watering the geraniums in the garden. But he felt too weary to invent a story, especially today of all days.

‘I know you’re in there, Arthur. You don’t have to do this on your own. You have friends who care about you.’ The letterbox rattled. A small lilac leaflet with the title ‘Bereavement Buddies’ drifted to the floor. It had a badly drawn lily on the front.

Although he hadn’t spoken to anyone for over a week, although all he had in the fridge was a small chunk of cheddar and an out-of-date bottle of milk, he still had his pride. He would not become one of Bernadette Patterson’s lost causes.

‘Arthur.’

He screwed his eyes shut and pretended he was a statue in the garden of a stately home. He and Miriam used to love visiting National Trust properties, but only during the week when there were no crowds. He wished the two of them were there now, their feet crunching on gravel paths, marvelling at cabbage white butterflies fluttering among the roses, looking forward to a big slice of Victoria sponge in the tea room.

A lump rose in his throat as he thought about his wife, but he held his pose. He wished he really could be made of stone so he couldn’t hurt any more.

Finally the letterbox snapped shut. The purple shape moved away. Arthur let his fingers relax first then his elbows. He wriggled his shoulders to relieve the tension.

Not totally convinced that Bernadette wasn’t lurking by the garden gate, he opened his front door an inch. Pressing his eye against the gap, he peered around outside. In the garden opposite, Terry, who wore his hair in dreadlocks tied with a red bandanna and who was forever mowing his lawn, was heaving his mower out of his shed. The two redheaded kids from next door were running up and down the street wearing nothing on their feet. Pigeons had pebble-dashed the windscreen of his disused Micra. Arthur began to feel calmer. Everything was back to normal. Routine was good.

He read the leaflet then placed it carefully with the others that Bernadette had posted for him—‘Friends Indeed’, ‘Thornapple Residents Association’, ‘Men in Caves’ and ‘Diesel Gala Day at North Yorkshire Moors Railway’—then forced himself to go and make a cup of tea.

Bernadette had compromised his morning, thrown him off balance. Flustered, he didn’t allow his tea bag enough time in the pot. Sniffing the milk from the fridge, he winced at the smell and poured it down the sink. He would have to take his tea black. It tasted like iron filings. He gave a deep sigh.

Today, he wasn’t going to mop the kitchen floor or vacuum the stairs carpet so hard that the threadbare bits grew balder. He wasn’t going to polish the bathroom taps and fold the towels into neat squares.

Reaching out, he touched the fat black telescope of bin liners that he’d placed on the kitchen table and reluctantly picked them up. They were heavy. Good for the job.

To make things easier he read through the cat charity leaflet one more time: ‘Cat Saviours. All items donated are sold to raise funds for badly treated cats and kittens.’

He wasn’t a cat lover himself, especially as they had decimated his rockery, but Miriam liked them even though they made her sneeze. She had saved the leaflet under the telephone and Arthur took this as a sign that this was the charity he should give her belongings to.

Purposefully delaying the task that lay ahead, he climbed the stairs slowly and paused on the first landing. By sorting out her wardrobe it felt as if he was saying goodbye to her all over again. He was clearing her out of his life.

With a tear in his eye, he looked out of the window onto the back garden. If he stood on tiptoe he could just see the tip of York Minster, its stone fingers seeming to prop up the sky. Thornapple village, in which he lived, was just on the outskirts of the city. Cherry blossom had already started to fall from the trees, swirling like pink confetti. The garden was surrounded on three sides by a tall wooden fence that gave privacy; too tall for neighbours to pop their heads over for a chat. He and Miriam liked their own company. They did everything together and that was how they liked it, thank you very much.

There were four raised beds, which he had made out of railway sleepers and which housed rows of beetroots, carrots, onions and potatoes. This year he might even attempt pumpkins. Miriam used to make a grand chicken and vegetable stew with the produce, and home-made soups. But he wasn’t a cook. The beautiful red onions he picked last summer had stayed on the kitchen worktop until their skins were as wrinkly as his own and he had thrown them in the recycling bin.

He finally ascended the remainder of the stairs and arrived panting outside the bathroom. He used to be able to speed from top to bottom, running after Lucy and Dan, without any problem. But now, everything was slowing down. His knees creaked and he was sure he was shrivelling. His once-black hair was now dove white (though still so thick it was difficult to keep flat) and the rounded tip of his nose seemed to be growing redder by the day. It was difficult to remember when he stopped being young and became an old man.

He recalled his daughter Lucy’s words when they last spoke, a few weeks ago. ‘You could do with a clear out, Dad. You’ll feel better when Mum’s stuff is gone. You’ll be able to move on.’ Dan occasionally phoned from Australia, where he now lived with his wife and two children. He was less tactful. ‘Just chuck it all out. Don’t turn the house into a museum.’

Move on? Like to bloody where? He was sixty-nine, not a teenager who could go to university or on a gap year. Move on. He sighed as he shuffled into the bedroom.

Slowly he pulled open the mirrored doors on the wardrobe.

Brown, black and grey. He was confronted by a row of clothes the colour of soil. Funny, he didn’t remember Miriam dressing so dully. He had a sudden image of her in his head. She was young and swinging Dan around by an arm and leg—an aeroplane. She was wearing a blue polka dot sundress and white scarf. Her head was tipped back and she was laughing, her mouth inviting him to join in. But the picture vanished as quickly as it came. His last memories of her were the same colour as the clothes in the wardrobe. Grey. She had aluminium-hued hair in the shape of a swimming cap. She had withered away like the onions.

She’d been ill for a few weeks. First it was a chest infection, an annual affliction which saw her laid up in bed for a fortnight on a dose of antibiotics. But this time the infection turned into pneumonia. The doctor prescribed more bed rest and his wife, never one to cause a fuss, had complied.

Arthur had discovered her in bed, staring, lifeless. At first he thought she was watching the birds in the trees, but when he shook her arm she didn’t wake up.

Half her wardrobe was devoted to cardigans. They hung shapeless, their arms dangling as if they’d been worn by gorillas, then hung back up again. Then there were Miriam’s skirts; navy, grey, beige, mid-calf length. He could smell her perfume, something with roses and lily of the valley, and it made him want to nestle his nose into the nape of her neck, just one more time please, God. He often wished this was all a bad dream and that she was sat downstairs doing the Woman’s Weekly crossword, or writing a letter to one of the friends they had met on their holidays.

He allowed himself to sit on the bed and wallow in self-pity for a few minutes and then swiftly unrolled two bags and shook them open. He had to do this. There was a bag for charity and one for stuff to throw out. He took out armfuls of clothes and bundled them in the charity bag. Miriam’s slippers—worn and with a hole in the toe—went in the rubbish bag. He worked quickly and silently, not stopping to let emotion get in the way. Halfway through the task and a pair of old grey lace-ups went in the charity bag, followed by an almost identical pair. He pulled out a large shoe box and lifted out a pair of sensible fur-lined brown suede boots.

Remembering one of Bernadette’s stories about a pair of boots she’d bought from a flea market and found a lottery ticket (non-winning) inside, he automatically slid his hand inside one boot (empty) and then the other. He was surprised when his fingertips hit something hard. Strange. Wriggling his fingers around the thing, he tugged it out.

He found himself holding a heart-shaped box. It was covered in textured scarlet leather and fastened with a tiny gold padlock. There was something about the colour that made him feel on edge. It looked expensive, frivolous. A present from Lucy, perhaps? No, surely he would have remembered it. And he would never have bought something like this for his wife. She liked simple or useful things, like plain round silver stud earrings or pretty oven gloves. They had struggled with money all their married life, scrimping and squirrelling funds away for a rainy day. When they had eventually splashed out on the kitchen and bathroom, she had only enjoyed them for a short while. No, she wouldn’t have bought this box.

He examined the keyhole in the tiny padlock. Then he rummaged around in the bottom of the wardrobe pushing the rest of Miriam’s shoes around, mixing up the pairs. But he couldn’t find the key. He picked up a pair of nail scissors and jiggled them around in the keyhole, but the lock remained defiantly closed. Curiosity pricked inside him. Not wanting to admit defeat, he went back downstairs. Nearly fifty years as a locksmith and he couldn’t bloody get into a heart-shaped box. From the kitchen bottom drawer he took out the two-litre plastic ice cream carton that he used as a tool box; his box of tricks.

Back upstairs, he sat on the bed and took out a hoop full of lock picks. Inserting the smallest one into the keyhole, he gave it a small wriggle. This time there was a click and the box opened by a tantalising few millimetres, like a mouth about to whisper a secret. He unhooked the padlock and lifted the lid.

The box was lined with black crushed velvet. It sang of decadence and wealth. But it was the charm bracelet that lay inside that caused him to catch his breath. It was opulent and gold with chunky round links and a heart-shaped fastener. Another heart.

What was more peculiar was the array of charms, spread out from the bracelet like sun rays in a children’s book illustration. There were eight in total: an elephant, a flower, a book, a paint palette, a tiger, a thimble, a heart and a ring.

He took the bracelet out of the box. It was heavy and jangled when he moved it around in his hand. It looked antique, or had age to it, and was finely crafted. The detail on each charm was sharp. But as hard as he tried he couldn’t remember Miriam wearing the bracelet or showing any of the charms to him. Perhaps she had bought it as a present for someone else. But for whom? It looked expensive. When Lucy wore jewellery it was new-fangled stuff with curls of silver wire and bits of glass and shell.

He thought for a moment about phoning his children to see if they knew anything about a charm bracelet hidden in their mother’s wardrobe. It seemed a valid reason to make contact. But then he told himself to reconsider as they’d be too busy to bother with him. It had been a while since he had phoned Lucy with the excuse of asking how the cooker worked. With Dan, it had been two months since his son had last been in touch. He couldn’t believe that Dan was now forty and Lucy was thirty-six. Where had time gone?

They had their own lives now. Where once Miriam was their sun and he their moon, Dan and Lucy were now distant stars in their own galaxies.

The bracelet wouldn’t be from Dan anyway. Definitely not. Each year before Miriam’s birthday, Arthur phoned his son to remind him of the date. Dan would insist that he hadn’t forgotten, that he was about to go to the post box that day and post a little something. And it usually was a little something: a fridge magnet in the shape of the Sydney Opera House, a photo of the grandkids, Kyle and Marina, in a cardboard frame, a small koala bear with huggy arms that Miriam clipped to the curtain in Dan’s old bedroom.

If she was disappointed with the gifts from her son then Miriam never showed it. ‘How lovely,’ she would exclaim, as if it was the best present she had ever received. Arthur wished that she could be honest, just once, and say that their son should make more effort. But then, even as a boy, he had never been aware of other people and their feelings. He was never happier than when he was dismantling car engines and covered in oil. Arthur was proud that his son owned three car body repair workshops in Sydney, but wished that he could treat people with as much attention as he paid his carburettors.

Lucy was more thoughtful. She sent thank you cards and never, ever forgot a birthday. She had been a quiet child to the point where Arthur and Miriam wondered if she had speech difficulties. But no, a doctor explained that she was just sensitive. She felt things more deeply than other people did. She liked to think a lot and explore her emotions. Arthur told himself that’s why she hadn’t attended her own mother’s funeral. Dan’s reason was that he was thousands of miles away. But although Arthur found excuses for them both, it hurt him more than they could ever imagine that his children hadn’t been there to say goodbye to Miriam properly. And that’s why, when he spoke to them sporadically on the phone, it felt like there was a dam between them. Not only had he lost his wife, but he was losing his children, too.

He squeezed his fingers into a triangle but the bracelet wouldn’t slip over his knuckles. He liked the elephant best. It had an upturned trunk and small ears; an Indian elephant. He gave a wry smile at its exoticness. He and Miriam had discussed going abroad for a holiday but then always settled upon Bridlington, at the same bed-and-breakfast on the seafront. If they ever bought a souvenir, it was a packet of tear-off postcards or a new tea towel, not a gold charm.

On the elephant’s back was a howdah with a canopy, and inside that nestled a dark green faceted stone. It turned as he fingered it. An emerald? No, of course not, just glass or a pretend precious stone. He ran his finger along the trunk, then felt the elephant’s rounded hind before settling on its tiny tail. In places the metal was smooth, in others it felt indented. The closer he looked though, the more blurred the charm became. He needed glasses for reading but could never find the things. He must have five pairs stashed in safe places around the house. He picked up his box of tricks and took out his eyeglass: every year or so it came in handy. After scrunching it into his eye socket, he peered at the elephant. As he moved his head closer then further away to get the right focus, he saw that the indentations were in fact tiny engraved letters and numbers. He read and then read again.

Ayah. 0091 832 221 897

His heart began to beat faster. Ayah. What could that mean? And the numbers too. Were they a map reference, a code? He took a small pencil and pad from his box and wrote them down. His eyeglass dropped onto the bed. He’d watched a quiz programme on TV just last night. The wild-haired presenter had asked the dialling code for making calls from the UK to India—0091 was the answer.

Arthur fastened the lid back onto the ice cream box and carried the charm bracelet downstairs. There, he looked in his Oxford English Pocket Dictionary; the definition of the word ‘ayah’ didn’t make any sense to him—a nursemaid or maid in East Asia or India.

He didn’t usually phone anyone on a whim; he preferred not to use the phone at all. Calls to Dan and Lucy only brought disappointment. But, even so, he picked up the receiver.

He sat on the one chair he always used at the kitchen table and carefully dialled the number, just to see. This was just silly, but there was something about the curious little elephant that made him want to know more.

It took a long time for the dialling tone to kick in and even longer for someone to answer the call.

‘Mehra residence. How may I help you?’

The polite lady had an Indian accent. She sounded very young. Arthur’s voice wavered when he spoke. Wasn’t this preposterous? ‘I’m phoning about my wife,’ he said. ‘Her name was Miriam Pepper, well it was Miriam Kempster before we married. I’ve found an elephant charm with this number on it. It was in her wardrobe. I was clearing it out …’ He trailed off, wondering what on earth he was doing, what he was saying.

The lady was quiet for a moment. He was sure she was about to hang up or tell him off for making a crank call. But then she spoke. ‘Yes. I have heard stories of Miss Miriam Kempster. I’ll just find Mr Mehra for you now, sir. He will almost certainly be able to assist you.’

Arthur’s mouth fell open.