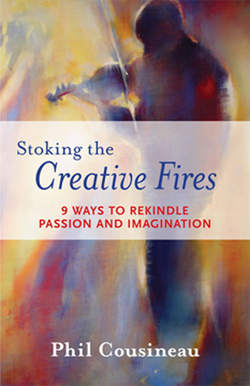

Читать книгу Stoking the Creative Fires - Phil Cousineau - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE RIVER OF REVERIE

ОглавлениеThe French philosopher Gaston Bachelard is the poet laureate of reverie. To my lights, he is one of the most sublime writers of the 20th century. In Poetics of Reverie, he wrote that reverie holds the capacity to exalt life and helps us to “inhabit . . . the world of happiness.” Tantalizingly, he adds, “If the dreamer had ‘the gift,’ he would turn his reverie into a work.”

That's the key, the trigger, the tipping or turning point. If you've ever been deeply moved by the feeling of a waking dream—perhaps at a great play or opera, on a canyon river, witnessing a child opening a birthday present, or as I was by Sandaldjian's oneiric creations—then you know what it means to fall down the sweet slope of reverie. With its roots in the soul of the dreamer, reverie is a gift from below, the opportunity to dream with your eyes open. As Bachelard writes, in some ineffable way, we actually seem to be defined by our reveries, even created by them.

To describe the waking dream demands something more than everyday language; the effort calls for words that, as many of us have suspected, cast a spell—words like “trance,” “delirium,” or “levitate”—tumultuous words that help describe the indescribable when we feel as if we've fallen through a trapdoor into another mood, or been lifted into another world.

“When in doubt, look it up,” my dad used to say. Though he's been gone for twenty years, the touch of his hand is still there on my shoulder, edging me toward my Oxford Unabridged Dictionary. Riffling through its pages, I discover that “reverie” is an early 17th-century French word for “rejoicing” and “revelry.” Later, I summoned Mr. Webster and found: “a daydream, a delirium, the condition of being lost in thought.” These worlds within words help me appreciate reverie even more.

But for me, the million-dollar question is how to turn the waking dream into the working dream. I've spent half my life tantalized by the possibility of consciously stoking the fires of reverie. Over the years, I've searched for compelling stories about creative people who lived for reverie, such as the painter Jean Arp whose ideal was to paint so others could view his work as he painted it, as if dreaming with their eyes open. I've wondered if we are on the verge of an evolutionary leap forward, as novelist Henry Miller believed: “The art of dreaming awake will be in the power of every man one day.” I've reveled in eccentric characters like Gérard de Nerval, who walked his purple lobster in the Luxembourg Gardens to prolong his hypnagogic reveries. And I doff my hat to comedian Steven Wright who describes the uncanniness of life as well as any phenomenologist: “I fell asleep in a neighbor's satellite dish and my dreams were seen on televisions all over the world.”

With her trademark rhythms and rhymes, the glorious Emily Dickinson tells us that “revery” is an essential component in the creation of nature itself.

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee, One clover, and a bee, and revery. The revery alone will do, if bees are few.

By extension, at the heart of our nature is the capacity for creativity, which likewise requires the self-luminous waking dream. It is in this state of spiritual readiness that creative souls sense the pull of destiny.

The history of art is crowded with creative people willing to do whatever it took to help them climb Jacob's Ladder—that age-old symbol of aspiration and revelation. For Marcel Proust, the taste of a simple cookie was enough to slingshot him back to childhood and then back to the present, a dream journey that inspired his epic novel In Search of Lost Time. Constantin Brâncuşi caressed woodcarvings he carried all the way from his homeland of Romania and read his native folk tales to reanimate his sculptures. In turn, English sculptress Barbara Hepworth visited Brâncui's studio to encounter the “miraculous feeling of eternity mixed with beloved stone and stone dust” and to feel the “inspiration of a dedicated workshop.” Honoré de Balzac sniffed rotten apples he kept in his desk drawer to evoke the wretched smells of the medieval Paris about which he wrote. Stephen Hawking, the wheelchairbound physicist, revels in the long stretch of time it takes him to get into bed each night to mull over the days unsolved science problems. Joanne Shenandoah walks through the woods of the Onondaga reservation listening to the voices of her ancestors. Think about what helps you slip into reverie, then find ways to keep it present in your life.

Jacob's Dream (Le rêve de Jacob), Old Testament engraving.

Barbara Hepworth sculpture garden, Cornwall, England. Photograph by Phil Cousineau, 1980.

Since childhood, I've devised ways to slip into daydreams, knowing I couldn't afford to wait for inspiration to “strike.” On of my earliest memories is hearing my best friend's mother discourage him from taking me too seriously because I was nothing but a daydreamer. All my life, I've gazed off into space, irking my parents, teachers, and friends. I sit and stare, walk and gaze, and do everything I can to stretch my dreams out as long as possible—in a hot shower, in the morning with the paper, at the bakery, on newly cut grass, listening to the chatter of kids playing baseball. Whenever I get a spark, I do what I can to keep it alive, fanning the flames until they roar—writing it down, sketching it, singing it, learning it by heart, or talking it out with friends and family. I'm happy to say it's an ancient urge.