Читать книгу Stoking the Creative Fires - Phil Cousineau - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHAT THEN SHALL WE DO?

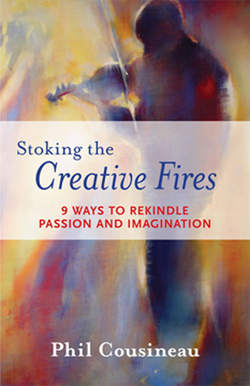

ОглавлениеFor R. B. Morris, a prolific singer, songwriter, and playwright from Knoxville, Tennessee, reverie is a subtle but powerful trigger. Recently he explained why:

It's the starting point for me, the threshold of creativity. It's the moment where all your other mental and physical functions fold into “dreamy thinking or imagining,” as Webster's says, “fanciful musing, a visionary notion.” If we really want to cultivate our creativity, we simply need to schedule our lives around the production of reverie. Frankly, I have to declare myself severely undisciplined in matters of creativity, but I do try to move toward those times of day when reverie comes easiest, such as the hours of waking or before sleep. The mind seems more willing then to throw off the harness of the world and allow the otherworldly to emerge. Of course, then one has to cultivate one's own process of observing and taking notes. Still, for all one's cultivation, the muse has a tendency to come and go as she pleases. So it's best to keep pen and paper at hand, even if I'm driving my pickup up on the mountain, and be ready to roll with the reverie whenever it occurs.

You know that a deep chord has been struck in you when a story, an image, a color, a drawn line, a melody taunts you until you figure out why you've been so deeply shaken. Australian director Peter Weir's film, The Year of Living Dangerously, did just that to me when it was released over twenty years ago. Rarely a day goes by that I don't hear the voice of actress Linda Hunt, playing a male stringer for a Malaysian newspaper at the time of Sukarno's overthrow, asking plaintively: “What then must we do?” She asks this at the crisis point when she takes a stand for all she believes in, even at the risk of her life. She asks it again and again in a fierce voiceover as her fingers fly across her typewriter keys. The challenging question is taken from Tolstoy's Confession, a searing account of his mid-life spiritual crisis when he saw “nothing ahead except ruin.” The answer came to him in a voice: “See that you remember.” Then he woke up.

With the whole world coming at us like a great thrashing wave, how do we recognize and remember reverie, especially when technology is now doing so much of the recall for us? There's only one trick I know of and it's not really a ruse. Write it down. Beat poet Gary Snyder once told me: “The only difference between writers and everybody else is that we always keep a thirty-nine cent notebook in our pockets. You never know when the inspiration might hit.” Many years later, I was startled to hear, in a radio interview with author Anne Rice, that she relied so heavily on daydreams that, for her, writing is daydreaming, which sometimes provides coded messages, including entire characters, like the twins in The Queen of the Damned. Jorge Borges ardently claimed in his Harvard lecture on craft that all writing is guided dream. Shadowbox artist Joseph Cornell said his work happened in a half-sleep. “Our dreams are a second life,” he said, “the overflowing of the dream into real life.” Photographer-artist Joanne Warfield tells me that reverie comes to her “in the form of enchantment or trance. I watch thoughts, ideas, and images floating by like leaves on a stream of consciousness. Sometimes when I'm in the midst of creating, reverie appears as inspiration for me to try something innovative—but I have to be alert, which can be hard when you're enchanted.”