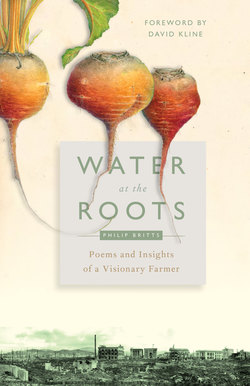

Читать книгу Water at the Roots - Philip Britts - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBruderhof members farming in Shropshire, England

PLOUGHING

——CHAPTER 2——

It’s time the soil was turned

So this new life began, with its new work. Philip laboured with the men in the fields and vegetable gardens. In spring the tractors ran day and night, ploughing, harrowing, and seeding the spring wheat. Often, the whole community would be called out before breakfast to help harvest vegetables, which had to be picked early to remain fresh for the farmers’ market. In autumn, pitching the sheaves into wagons and stacking them in a giant shock was a communal event, as was the day the threshing machine arrived on its round of all the local farms.

Philip loved it all – the seedtime and the harvest – and his poems from this time reflect this newfound joy.

BREAKFAST SONG

Come let us to the fields away,

For who would eat must toil,

And there’s no finer work for man,

Than tilling of the soil.

So let us take a merry plough,

And turn the mellow soil,

The land awaits and calls us now,

And who would eat must toil.

1940

THE PLOUGH

Now let us take a shining plough

And hitch a steady team,

For I have seen the kingfishers

Go flirting down the stream.

And sure the Spring is coming in –

It’s time the soil was turned,

It’s time the soil was harrowed down,

And the couch grass burned.

For we have waited for the chance

To turn a furrow clean,

And we have waited for the cry

Of peewits come to glean.

Now there’s work from dawn ’til sunset,

For it’s time the plough awoke,

And it’s time the air was flavoured

With the couch fire smoke.

1940

FINGERPRINTS OF GOD

“Whenever I meet a man,” he said,

“I look him low, I look him high,

To see if a certain gleam is born,

An inner light, deep in the eye,

The light of eyes that see in growing corn

Not only grain, not only golden bread,

But sweet and plain, the fingerprints of God.

What for a man is it, who cares

Only for harvest and the threshing feast,

Sees the reward before the growth of Love,

Who looks impatient at the slim green spears

That tremble under grey October skies

And scorns all but the ripened head?

God is not seen only at harvest time,

But he is here, in winter-sleeping sod,

And half his glory stands about our feet

In the low lines of green young growing wheat.”

1940

EXPERIENCE – BEWILDERMENT

I have stood all day on sodden earth,

Beneath the heavy hand of weeping skies,

But golden fancies hammered at my brain,

An endless count of flying wonder-thoughts,

Pell-mell upon each other, and again

Forgotten, like the dance of dragonflies.

1940

The community happened to be close to several Royal Air Force bases – obvious targets for bombing raids. The men took turns serving as night watchman for the community.

THE END OF THE WATCH

There’s a crowing of cocks, and a paling of stars,

And the hours of the watch are far on;

There’s a flush in the east, and the pipe of a bird,

And the last of the starlight is gone.

The darkness thins out, and the new world appears.

The watchman prepares to depart.

Let him go to his rest with the sun on his face

And the splendour of stars in his heart.

1940

Now is the harvest of death

During the spring and early summer of 1940, while Philip was planting and hoeing, Germany invaded Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. British troops were rescued from Dunkirk, but only after thousands had been killed or taken prisoner.

THE HOUR ON WHICH WE LOOK

Now is the harvest of Death,

Now the red scythe-blade of slaughter

Sweeps through the children of Eve.

We stand in a circle of silence,

The wings of the Reaper are hissing –

And what could our speaking achieve?

And we, as we stand in our silence,

Hear the laugh of the sower of fate,

Who scattered the seed in the hearts of the tribes,

And who reaps now the hate.

Only the music of a wild wind in the trees,

Or the rumble of thunder, the roar of the rain,

The shouting of demons who ride on the storm-winds of wrath

Can tell of the tempest that howls like a wolf on the plain;

Where the earth carried wheat, and the waters were sweet,

But now stink with the blood of the slain.

1940

Germany defeated France in just six weeks, and turned its eyes to its next target across the English Channel. Britain made preparations for the expected invasion.

Now that the people of England were rallying to fight for their country, they had little patience with war resisters. The government, however, provided tribunals to discern whether or not a conscientious objector to war was genuine in his request for alternative service or unconditional exemption.

Philip was called up before such a tribunal. On February 27, 1940, a local newspaper, the Evening Advertiser, reported on his case:

Swindon Man’s “Love Beats All” Theme at Tribunal

Bruderhof Man’s Conscience:“A Christian Cannot Take Up Arms”

A probational member of the international community at the Bruderhof, Ashton Keynes, near Swindon, was an applicant for total exemption from military service before the South-Western Tribunal for Conscientious Objectors, at the University of Bristol yesterday. He was Philip Herbert Cootes Britts, and he was accompanied in court by several fellow members, bearded young fellows, who attracted considerable attention by reason of their unusual appearance.

Britts, in his written statement, applied for complete exemption from any form of war service because of his belief that a Christian cannot take up arms or use violence against his fellows; neither could he help others to do so. For the last five years there had been no question in his mind about that, he averred.

“In the spring of 1939,” the statement proceeded, “I decided to take part in organised pacifism and began to promote my views among others. During the summer I addressed the local Bible classes on this subject and set about organising a group of the Peace Pledge Union in Kingswood, Bristol. I acted as its secretary until I came to the Bruderhof on 26 November. I cannot accept any conditional exemption, and shall refuse any form of alternative service.”

The judge was satisfied that Philip’s beliefs were genuine and granted him an unconditional exemption.

It was no escape from conflict that Philip sought, but a different struggle. “This is the meaning of brotherhood,” he would write eight years later, “– not a haven of refuge, but a joyous aggression against all wrong.” What’s more, there would be no end to this battle, no decommissioning and resting on one’s laurels, no growing old and tepid.

THE OLD MEN WHO HAVE FORGOTTEN WHAT TO DO WITH LIFE

They spoke of high adventure of a thousand mighty sorts –

Of bareback rides on foreign plains

And nights in foreign ports;

They laughed and cursed and downed their beer,

And all would talk and none would hear,

The bar was thick with noisy cheer

As the men sat drinking.

But one man sat in quiet, alone,

In one dim corner, sat and gazed.

He told no story, roared no laugh,

But sat and stared as one amazed.

The man sat thinking,

And ever in his mind there burned the thought,

Here is the poison – where the antidote?

Here is the evidence that men forget.

These have forgotten all the pith of Truth:

And most men with them, that I ever met,

In boasting age or swift careering youth,

Have missed the true adventure, missed the thrill

Of that great ride where they could drink their fill

Of wonder and of danger and of strife –

They have forgotten what to do with life!

These lusty men grow old

And gibber freely in their age

Stale stories of a hectic yesterday.

These lusty men grow old,

And all their hectic yesterdays

Are now like froth upon a glass of beer.

These lusty men grow old

And spend an idle eventide

Yarning about dead deeds with dying words,

And all their strength, their striving, and their fear

Is like a gust of wind, and all their feats

Like thistledown adrift in city streets.

But who can show strong men, as these,

The things that will abide,

The one Adventure, one great Quest,

From which there is no pause nor rest

When once the search is tried;

Where those who search and struggle

Win courage from defeat –

And, daring, drink the wells of Death,

And find the water sweet?

There is but one Adventure,

The seeking for the Truth,

One prize for those who find it –

Everlasting Youth.

When they were born, they knew it,

The men who sit here yet;

And every sunrise tells them, but always they forget.

1940

Let there be no fallow in my heart

With Great Britain at war, what had become of the Christian peace witness? In 1948, Philip would write:

If a man who had been closely associated with Jesus of Nazareth were to revisit the world today, with no knowledge of the intervening history, it would seem strange to him that the numerous and widely-followed “Christian” churches are as perplexed and helpless in the face of the general dilemma as is the rest of humankind. He would have heard Jesus proclaiming a new way of love, a new kingdom of peace, and he would now find whole nations claiming to be his disciples and, not only living in violence, injustice, lying, and impurity equal to that of the pre-Christian world, but even using his name to bless and justify their wars.

Where shall we look, and what have we to say in face of this confusion? … Is it not important that there should be some place in the world, however small, where people actually live in brotherhood and justice and peace – and that we give our lives to this cause?

To give their lives to this cause was precisely what Philip and Joan decided to do. In the spring of 1940 they asked to become members of the Bruderhof, making lifetime vows of commitment.

“WHEN I HAVE GROWN”

When I have grown to strength of heart and mind,

Then let me still lie helpless on thy knee,

Still raise my empty hands towards thy face,

And let thy love, alone, smile out from me.

I am but earth, unless thou work in me

And make my earth bear fruit in every part.

Wound me, then, deeply, with thy plough of love,

And let there be no fallow in my heart.

1940

My family had joined the community shortly before Philip and Joan came. We children felt an affinity for him – he was quiet, thoughtful, awake to joy, and willing to spend time with us. That fall, Philip wrote this story, illustrated it with childlike black and white sketches, and gave it to my younger brother, Anthony, and me for my ninth birthday. I am no longer sure what prompted it, but I may have asked him why there were flowers in the woods in springtime, but not in the summer.

WHY AUTUMN COMES

Barbara had a big tabby cat, who was very old and very, very wise. Nobody knew how old he was, because he was already there when the community came to the land.

Nobody knew how wise he was either, but they said he was the Wisest-of-all-Cats. Indeed, he was able to talk, and when Barbara was puzzled, he used to tell her How-things-came-about stories.

One day when the brown and golden leaves were spinning down from the trees, and the Wisest-of-all-Cats was asleep by the stove, Barbara poked him with her finger and said, “All the leaves are falling off the trees, Cat, and there is a thick blanket of them on the ground. Why does it happen, and how did it come about?”

The Wisest-of-all-Cats stretched himself and said, “It’s a story that goes back to the First Days, but I will tell you all about it.”

In the days when the world was very young, a little girl was skipping over the grass, looking for flowers. And there were flowers everywhere.

The green carpet of the grass was spotted with many colours, and flowers grew together in little groups, in every possible place. Some grew in the sun, and some in the shade of rocks.