Читать книгу Water at the Roots - Philip Britts - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

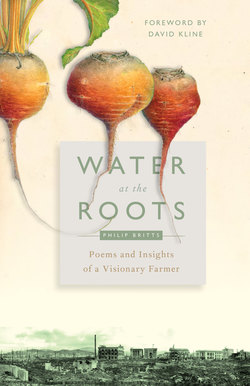

ОглавлениеBristol, England, city center, 1920s

WILDERNESS

——CHAPTER 1——

Look up to see if the God I serve has seen

The town of Honiton, in Devon, southwest England, is surrounded by rich farmland. The River Otter flows nearby, leading down to the sea some ten miles to the south. Footpaths trace their way through the countryside. Here Philip Herbert Cootes Britts was born on April 17, 1917, and it was here that his lifelong love of farming and nature, hiking and camping, poetry and song first took root.

By the time he was four, though, his family had moved to a suburb of Bristol, a busy port city famed equally for its cathedral and its urban poverty. Here, his sister Molly was born.

Most of Philip’s childhood memories were centred on Bristol, which was plagued by crime and unrest at the time, but from early on he preferred the countryside.

Philip went to grammar school and then looked for any kind of work to earn money for his university studies. He worked in a quarry, then took care of a wealthy man’s orchid house. Later in life, Philip would tell stories about his escapades during these years. One ended in a major motorcycle accident that proved to be a turning point in his life.

Little more is known of his early life, but his earliest poems give a window into his thoughts.

ALONE

When the night is cold and the winds complain,

And the pine trees sigh for the coming rain,

I will light a lonely watch-fire, near by a lonely wood,

And look up to see if the God I serve has seen and understood.

I’ll watch the wood-ash whitened by the licking yellow tongues,

I’ll watch the wood-smoke rising, sweet smoke that stings the lungs,

See the leaping, laughing watch-fire throw shadows on the grass,

See the rushes bend and tremble to let the shadows pass,

While my soul flies through the forest, back a trail of weary years,

And the clouds, as if in pity, shed their tears.

Oh, I do not want their pity for a trail that’s closed behind,

Though all the things on earth combine to play upon the mind.

I must keep on riding forward to a goal I’ll never find –

What matter the eyes have seen so much that the soul is colour-blind?

1934

It’s not difficult to see the influence of the popular poets of the day – William Butler Yeats, John Masefield, A. E. Housman – on the young Philip’s work.

“I SENT MY SOUL SEARCHING”

I sent my soul searching the songs of the ages,

The hearts of all poets were bared to my eyes,

Though I read golden thoughts as I turned golden pages

The echoes fell faint as of songs that were sighs.

I weighed up the greatness of all who were greatest

Whom the world had called strong and the world had called wise,

But the song that they sang from the first to the latest

Fell back from the portals of thy Paradise.

1934

Am I dreaming this wilderness?

Philip’s spiritual search did not cut him off from the political and social drama of his time and place. Rather, his questions thrust him into the heart of things. The 1930s were turbulent years for Europe and beyond, years of uncertainty and disillusionment. Socialism and a strong peace movement in England held promise, but rumours from Russia soon cast shadows on communism, and economic meltdown on the West’s own grand visions of humankind’s continuous progress.

This suffering soon struck close to Philip. Not far from Bristol, on the other side of the River Severn estuary, are the coal-mining valleys of South Wales. These valleys were hard hit during the Great Depression. There were hunger marches from 1922 to 1936, some nationwide, some local, to appeal to the government for help. In 1931 a hunger march of 112 people – many from the Rhondda Valley – marched to Bristol, their slogan “Struggle or starve.” The demonstration was broken up by mounted police.

WORKING IN A CITY

There are so many songs that need to be sung.

There are so many beautiful things that await

The sensitive hand to pick them up

From this strange din of busy living.

I hear an echo in my sleep,

But I, caught up in the tide, like the rest,

Must spend all my life for the means to live:

I starve if I stop to sing–

Yet this dull murmuring

Will keep my heart forever hungering.

1936

The news from abroad was troubling as well. In 1936 both Hitler and Mussolini were consolidating their power. Germany and Italy, the Axis Powers, became allies. In March 1936, Hitler moved twenty thousand troops into the German Rhineland. Europe was on edge.

WHILE WE RE-ARM

Behind the mountains of imagination,

Screened off by passing mirth and passing tears,

The mind of mortal man is holding unawares

The harvest of a million weary years.

Some time, some place, some unsuspected dreamer

Will catch an echo of the far refrain,

And by his visions in a night of watching,

Will break the misty barriers of the brain.

His song shall shake the souls of politicians,

And while the craven church still watches, dumb,

The hands of men shall grasp at tools, not weapons,

And womanhood shall sing that peace has come.

1936

SANCTUARY

I may not move, while that lone tuft of cloud

Still holds the fairy hues,

An opal thrown against the sky;

And were this shovel in my hand a waiting sword,

And all the great crusaders beckoned me –

I could not move, until the glory passed.

1936

UPON A HILL IN THE MORNING

The timid kiss of the winter sun,

The waiting faith of the naked trees,

The breath of a day so well begun,

Take what you will and leave me these.

Leave me my love and leave me these,

Leave me a soul to feel them still,

Better to be a tramp, who sees,

Than a monarch blind upon a hill.

1936

THE DREAMER

I stood in flowers, knee high,

Dreaming of gentleness,

Dreams, in the promise of a shining sky

That I should make a garden from a wilderness;

I would subdue the soil and make it chaste,

Making the desert bear, the useless good,

With my own strength I would redeem the waste,

Would grow the lily where the thistle stood.

The while I dreamed, the flowers were sweet,

Now that the flowers are gone, it seems

They never bloomed except in dreams.

There are no blossoms at my feet,

The bald blue sky is lustreless,

The flowers had never been, except in dreams,

It was a dream … this is a wilderness.

My eyes are tired of the skyline,

My feet are tired of the sand,

I am as dried of laughter as the sun-scorched land,

As the staff in my sun-scorched hand.

Had I not dreamed so long,

Not dreamed of so much beauty, or such grace,

Mayhap I could have trod a quieter path,

With other men, in a green, quieter place …

My ears are tired of the silence,

My heart is tired of the toil.

If I sowed any seeds, they have perished,

Nothing is living in the soil.

From the dewless morn I have been here,

Now the day is nearly through;

The tyrant sun sinks down at last,

The colours fade, the sun departs.

Was there a glory – or was that a dream?

I hear, or think I hear, faint music:

Not the song of birds, which are fled from me,

Not the humming of bees, on dream blossom,

Not the voices of happy men …

I strain to catch the sound again …

Oh! let the music swell, slowly,

Mould a stately music, to soothe the pulse of the earth,

Develop the theme –

Do I pray? or hope? or dream?

I do not know if I dreamed I stood in a garden.

(Was it a dream, the flowers’ caress?)

Or did I dream of the sun and the sand –

Am I dreaming this wilderness?

1937

But while both spiritual and political questions demanded answers, there were others of a more personal nature to be asked as well. Philip had known Joan Grayling, his future wife, since childhood. We can surmise she is the muse in Philip’s sometimes stormy poems of love.

DISTRUST

He saw the clouds creep up in stormy herds,

He saw clouds hiding the eternal tors

And clouds like a flock of wild white birds

Winging across the sky towards the moors.

Walking alone he saw the high clouds reeling

In the changing skies,

But his eyes were afraid and seeking,

The voice in his heart was speaking,

And he felt that the clouds were a ceiling

Darkly forbidding his petulant spirit to rise.

Solitude mocked silently.

Sickened, he asked, “Oh, has she faith in me –

The faith that makes men heroes?”

Long after the echo, came a faint reply:

“Find in yourself a faith as true,

Faith is made, not of talk, but deeds,

Lest she go loving on, but you –

Go back to a harvest of weeds.”

1936

VALENTINE VERSE

If we should walk in moonlight,

My valentine and I,

In slow step, by a stream of stars

Where water lilies lie:

Where the elm trees stand in silence

Down the hill like a line of kings,

And alone, in a world that listens,

The nightingale sings:

Sweet the smell of the meadow,

Cool the kiss of the breeze,

A dainty foot and a steady foot,

Step slowly under the trees.

If we should walk in moonlight,

While we and our love are young,

We should hear a softer music

Than the nightingale has sung.

1937

We heard a call and hurried here

Philip graduated from the University of Bristol in the spring of 1939. Now he had a degree in horticulture and a title: Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society. He seemed poised to enter a secure position in one of England’s institutions of learning and research. In June he and Joan were married. The couple moved into a beautiful stone house with a walled garden, which they had recently purchased.

But war was in the air, and Philip had meanwhile become a convinced pacifist. What was he to do if he was called up for military service?

Philip was not alone in his stance. The Peace Pledge Union, founded in 1936, asked its members to sign this statement: “War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determined not to support any kind of war. I am also determined to work for the removal of all causes of war.” The Great War had been “the war to end all wars,” but all the blood and sacrifice seemed only to usher in new bloodshed. In her autobiographical Testament of Youth, Vera Brittain recounted the losses of her generation, to conclude: “Never again.” Philip had joined the Peace Pledge Union (PPU) in 1938, participating with great enthusiasm. He spoke about war and peace in Sunday school classes and started a local PPU chapter in 1939. Joan shared his faith and his commitment to peace.

News from the Continent got worse. Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938 was followed by his invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Two days later Britain declared war on Germany.

Winston Churchill gave rousing speeches: “We are fighting to save the whole world from the pestilence of Nazi tyranny and in defense of all that is most sacred to man…. It is a war, viewed in its inherent quality, to establish, on impregnable rocks, the rights of the individual, and it is a war to establish and revive the stature of man.”

The peace movement caved in. Hundreds broke their pledge never to support war again and threw their energy into defending England. Even the chapter of the Peace Pledge Union that Philip had started succumbed to the militant mood sweeping the country: most members rushed to defend the homeland against Hitler’s threatened invasion.

Then came a real blow: England’s churches followed suit, joining its politicians in calling on the populace to support the war effort. But as lonely as Philip and Joan felt in their commitment to peace, they would not yield. They still hoped that it was not too late to avert war.

INSANITY

We see mad scientists watching tubes and flasks,

Staring at fluids with the power of death;

Mad engineers that work out guns of steel

And make great bombs that carry poison breath.

We hear mad statesmen speak of peace through arms,

We read wild praises of the power that rends;

And in the pulpits of the church of Christ

Mad clergy tell us to destroy our friends.

We hear the drone of planes that townsmen build

To scatter death and terror in the town;

And hear the roar of tanks on country roads

That will mow down our brothers, crush them down.

Lest this should happen, still more ships are launched;

To ward off war, we spend more gold on arms,

And lest the voice of Christ is heard to groan,

We sound, more loudly, still more wild alarms.

UNDATED

England was mobilising. In May 1939 Parliament had passed the Military Training Act: twenty-one- and twenty-two-year old men could expect to be called up for six months of military service. The day war was declared, all men between the ages of eighteen and forty-one became liable for call-up.

Philip had dreamt of “so much beauty” and of “making a garden in the wilderness,” but what did the God he served want him to do in the realities of everyday life – in “the din of busy living” and the preparations for war?

Several years later, Philip told a story of this time: He had been in church listening to the minister. Suddenly the sermon became a call to arms, fanning patriotism, praising heroism, referring to Germans as monsters. Philip rose from his pew, walked quietly up to the pulpit, and asked the minister, in the slow, deliberate way that farmers have, whether he could give him a few minutes to address the congregation. The minister agreed, and Philip spoke: “Jesus said we should love our enemies.”

And then, one day in the fall of 1939, Philip and Joan read a newspaper article about a pacifist group in England whose members tried to live by the Sermon on the Mount, following the example of the early church. At this community, the Bruderhof, which had been recently expelled by the Nazis, Britons and Germans were living and working together as brothers and sisters. Was this what they had been looking for? Philip and Joan had to find out for themselves. That October, they cycled twenty-seven miles to the Cotswold Bruderhof. They stayed for a week and decided to return. Here was a way forward, an answer to their search.

“The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which someone found and hid; then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field” (Matt. 13:44). Sells all that he has – nothing less is sufficient, all is nothing compared with the treasure. Let the field be the divine counsel of God. Hidden within it the treasure – the kingdom – the precious secret of the field.

In November 1939 Philip and Joan sold their house, left family and friends, and moved to the Cotswold community. Giving away all his possessions and launching into an uncertain future, Philip jotted these lines: “How rich is a man who is free from security. / How rich is a man who is free from wealth.”

CAROL OF THE SEEKERS

We have not come like Eastern kings,

With gifts upon the pommel lying.

Our hands are empty, and we came

Because we heard a Baby crying.

We have not come like questing knights,

With fiery swords and banners flying.

We heard a call and hurried here –

The call was like a Baby crying.

But we have come with open hearts

From places where the torch is dying.

We seek a manger and a cross

Because we heard a Baby crying.

CHRISTMAS 1939

“THE OLD ROAD TIRES ME”

The old road tires me

And the old stale sights,

And I must wander new ways

In search of sharp delights

With new streams and new hills

And smoke of other fires;

For a new road tempts me –

And the old road tires.

1940

This little poem opposes the patriotic nostalgia that ran through both Britain’s war propaganda and the popular poetry of Philip’s youth. Unlike Housman’s Shropshire lad, he did not long for home, and, much as he loved the earth, he would never be wedded to one particular patch of ground. He had heard a call, and was ready to “wander new ways.” But he could not have known how very far from his native Devon these ways would take him.