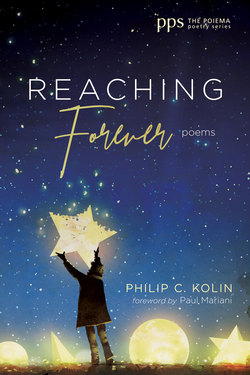

Читать книгу Reaching Forever - Philip C. Kolin - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеPaul Mariani

Begin with water. Begin with Genesis and the flood. Begin with the Creator of it all, that incredibly generous and consummate artist. It is we creatures who—the poet reminds us—must be baptized, submerged, into the mystery if we are ever going to begin to adequately respond to that creation with its vast waters defined by those “coral and turquoise,/reefs bejeweled with fins and fans.” It is we who will have to be “pooled into fonts,/wells, and tides” if we are ever to “acquire a majesty” which was never of our making. Be still, reader, and immerse yourself in the infinite symphony of the universe, and trust in this poet to guide us.

Philip Kolin has worn many hats over a long and illustrious career. He’s a scholar-professor steeped in literature and religion, a teacher, an editor, and a searcher. But above all he’s a poet. And not just any kind of poet, but a prophetic poet, a viable witness to the world in all its rainbow colors as well as the spectrum of black, a man who has spent the better part of his life listening for God’s Word. He can read creeks and ponds and rivers and seas, but especially the Great Mississippi the way William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams and Flannery O’Connor and the Eliot of Dry Salvages have read the river.

For me, one of the strongest poems in this intense and brilliant collection is “The River Burial,” where “the old Mississippi travels/ across the seas down to the Jordan,” for this is after all the old Bible belt. “The preacher smothers and submerges each sinner,” he shows us, having witnessed such river baptisms often enough, for “air is vanity going under the dark river” and it is God who will “rinse wrath and lust out of each of the convicted.” And yet, the poet knows all too well that the sins of us mortals don’t ever seem to disappear completely. For the truth is that they seem to “keep coming back to shore” as the river “returns the remains of the dead each night.”

Consider the fourteen-year-old African-American, Emmett Till from Chicago (like the poet himself) visiting family down south, for instance, only to be savagely beaten and murdered by two whites because he allegedly wolf-whistled a white woman, his broken body weighted down in the Tallahatchie River in the Mississippi Delta. Kolin has written extensively about Till, still haunted by the boy, who keeps appearing again ghost-like, plaintively, in these poems.

Water, life-giving water: it’s everywhere in these poems. Including the Gulf, where a blind man feels the sun on his back, and a veteran strides the beach, apparently oblivious to the world in front of him, where two widows console each other, and where

A teen just out of rehab rushes

to the beach, his guitar slung across

his tattooed chest and pockmarked arms

to serenade the waves that do not listen.

Or again, there’s that Pentecostal morning on the beach, a glimpse of heaven, where we have a hint of what it means that the last shall be first, and the first last:

Jamaicans free for the day

from stocking shelves at Wal Mart,

their black bodies glistening

in the whitecaps; Vietnamese

grandfathers maneuvering toddlers

through the foamy surf,

three Serbian boys diving

headlong into the waves.

And the drawl of speakers

from countless Southern towns

called to the beach.

Each heard what the waves were saying.

“Then too there are those seven brown pelicans” flying off into the distance of the Gulf, the last rays of the setting sun catching them as they break “free of the land now, “ while the hungry cries of the quotidian gulls go on “pecking the sloshing tides.” Watch carefully, the poet tells us, for isn’t this after all

a picture

of what awaits those who will travel

between twilight and dark

to enter light that is never framed.

And so with the seasons, evolving over millennia along with the formation of our present world, from lava rock to the first seeds of the kingdom of grass, for God saw that it was good. And then there are the gulls and the pelicans and the dogs and the rest of it in Kolin’s Adamic re-enactment. Ah, “How glorious if the earth coursed/ through lush pampas year round,” he reminds us. But the earth “must compass the dark seasons, too,” “the prickly dismantling of fall, / the white comforter of winter/ above a crypt of cold stark seeds.”

But, always, there’s the great return. Fresh water again with that much-needed rain, all of it stitched together in the poem’s closing rhymed couplets, as we celebrate

spring’s tears for their return

and the bravo of April’s resurrection,

green shafts with a crown of soft rain,

the kingdom of grass come again.

Oh, there’s darkness here, enough to satisfy even a Cormac McCarthy, one sees. As in “The Black Blizzard,” where the poet evokes those terrible dust storms of the Thirties, when dust begat dust and the soil

we lived on and were buried in

whipped up and [was] swept away by winds

from a sky that seemed to harbor

its own revenge

And where families moved west, out of an Eden they had helped to destroy, to settle in places like Los Alamos, place of the poplars, where “We thought we could harvest the sky once more,” and where in another short decade new clouds, far more ominous still, “billowed like white mushrooms, /ready for the picking.”

Such a plethora of riches in these poems—many of them dark meditations which grow ever darker as we stare into the face of unremitting evil, as in “Sons of Moloch,” part of the aptly-named “Wolves” section, where African Voodoo priests tell men plagued with AIDS that they can rid themselves of their disease by coupling with young virgins. Or there’s “A Simple Ten-Minute Procedure,” which reveals the too-often-unspoken-of aftershocks of abortion, where the lost baby

still woke her at night

with soft screams that continued

for hours. Her husband never heard

them, no matter how hard

she tried to make him listen.

The child cried about why and how

his life could go so quickly

before he could enjoy breathing.

But all he had

were memories of forceps

cradling him down

a sterile sink, a savage womb.

But then again there’s the mercifully longer section called “Sheep,” where Kolin focuses once again on our worthy and underrated marginalized. Take, for instance, Christmas in New York for that homeless man in his cardboard manger, “His welcome mat... printed in one language” and “read in another,” who just might read “angels in the snowflakes/ raining down,” as he “listens to the moon splashing/ light on him at the Winter Solstice.” Or the orphan, recalling a drug-addicted “mother’s purple eyes/ and frosted lips,” feeding him through a needle.

In one of those rare moments, the poet turns the lens on his own scarred youth in “A Night in Lisle,” a Catholic orphanage just outside Chicago’s limits, where a small boy, separated for a time from a mother unable to find work, hopes to be comforted by the nun at the night desk “from which sole light emanates,” but who instead sends him scurrying back to his bed. “We prayed to the Father to rescue us,” he tells us,

but he came only a few times each year

and then to carry one or two of us off

with a cold smile, folded now under

rubber sheets zipped,

to be harvested.

Mercifully, mercifully, there are God’s sheep as well to celebrate: those who smell like God’s sheep because they do God’s work. Like God’s bakers, those monks from St. Benedict in Louisiana, who three days a week cross Lake Pontchartrain to feed those “exiled from their own identity/ in the national void of halfway/ houses, shelters, nursing homes, jails,” like Brother Joseph in his “old delivery van – a 1999 Chevy Astro– . . . packed full of bread” then returning to the monastery “bursting/ with the scent of myrtle.” Or Father Daniel Francis Derivaux, like Merton a Gethsemane monk, “called to be a prisoner of Christ” “at Parchman Penitentiary/ teaching unschooled monks in striped habits/ to sigh the name of Jesus.” Or one more nameless unwed mother, trying desperately to feed her baby from the leftovers of those vast dumpsters in our indifferent cities.

And on it goes, in poem after blessed poem, forever reaching out toward God’s forever, which we sheep have been promised. And yet, and yet. In spite of the darkness and the pain and the losses, what can we—approaching our own deaths—hope for, after all, when God finally arrives? “Let your eyes write/new tears for a pilgrimage/ to a place you cannot see,” this poet who has clearly paid the price tells us.

Wait for the darkness, for it is out of the darkness, as the prophets and the saints have so often reminded us, that he will call for us. And don’t try to image what being in His image will mean. That is beyond our imaginations, for God “lives in infinity,” and “whispers fire and speaks/ in endless vowels.” And as His train passes by, as it did for Moses on that high mountain, it will evaporate continents along with our “black-plumed sins,” and suddenly, mercifully, astonishingly, you will “realize you do not/ have to wear/ your body anymore.”