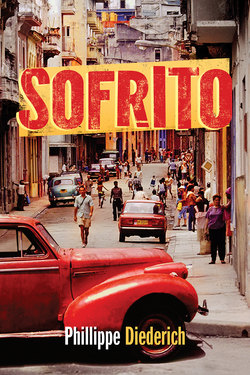

Читать книгу Sofrito - Phillippe Diederich - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

“I prefer my rice cooked with a few habanero peppers. Not just for a little spice, but for the familiar flavor of my mother’s kitchen.”

—Cuban heavyweight boxer, Téofilo Stevenson

after winning his third Olympic gold medal. Moscow, 1980

Frank moved quickly around his hotel room, looking for peepholes, microphones, bugs, cameras, anything suspicious. He mimicked the spy movies he had seen, running his hands over the plain wood furniture, the lamps, the curtains. He checked behind the mirror and under the bed.

Nothing.

He dug out the card where Justo had written his brother’s contact information and asked the operator to put the call through. After a few tones and clicks, she came back on the line or—as Frank suspected—had never left the line and informed him there was no answer.

He set down the receiver and stared at a faded photograph of the Morro Castle hanging on the wall. His mind spun like a pinwheel, thoughts and fears racing to catch up to the present. He unpacked his bag. He placed half his cash in the room’s safe deposit box and spread the rest between the pages of his soft cover copy of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, which he had brought specifically for that purpose.

It was Monday evening. His flight out was on Sunday morning. That gave him five full days to get the recipe. He had no time to waste. He tried Justo’s brother’s number again, but there was still no answer.

The noise from the courtyard and the lobby filtered up to his room. It sounded like a party. He went downstairs and took inventory of the security guards in the lobby. They were big men in beige guayabera shirts. One was posted by the elevator, another at the stairs. Two stood by the hotel’s entrance and another near the patio bar where the trio was playing Guantanamera for what must have been the fifth time.

It was dark out. At the entrance to the hotel, the doorman was flirting with the same three women Frank had seen earlier. They appeared to be old friends, but as Frank approached, the doorman quickly separated himself and greeted him with a formal nod.

Frank’s gaze lingered on the pretty girl with the blue dress. In less than a second he took in the outline of her shoulders, her deep reddish skin and the arch of her back as it curved down her legs all the way to her magenta colored toenails.

She noticed him looking and smiled, but one of her friends had already moved past her and was reaching for Frank’s arm. The doorman pulled her back.

“Do you know the restaurant, El Ajillo?” Frank asked the doorman.

“Cómo no, would you like a taxi, caballero?”

“Oye,” the pretty girl in the blue dress said loud enough for him to hear. “Listen to him. He almost sounds Cuban.”

“Ya, Marisol.” The doorman waved her away. Then he stepped outside and signaled a man who was sitting on the hood of a turi-taxi parked across the street.

Marisol’s friend approached him again. “What’s your name, amigo?”

“Frank.”

“Español?”

He shook his head. The girl glanced past him at the doorman who was making his way back into the hotel. “You want company tonight?”

He had never been good with women. He was shy. In all his relationships, it had been the women who approached him. When he entered into a relationship, he hung onto it with mild apathy until it became obvious to both parties that love had never been part of the equation.

The doorman came back and shooed the girl away. “Yoselin, por favor.”

Frank stole a quick glance at Marisol, then walked out to the car.

“Oye.” Marisol caught up with him as he reached the taxi. “You don’t like my friend?”

“It’s not that—”

“You don’t think she’s pretty?”

Yoselin and the other girl were staring at them, waiting.

“Everyone thinks she’s pretty.” Marisol crossed her arms. “Italians in particular.”

There was something easy about her, like they’d been friends a long time ago. Frank leaned against the side of the taxi and crossed his arms over his chest. “I’m not Italian.”

“¿Entonces?”

“Americano.”

“No me digas. Yoselin has cousins in Miami.”

Frank smiled. He knew about jineteras, Cuba’s famous prostitutes. His first instinct was to walk away, but then he noticed every foreign man around the Sevilla had a pretty Cuban woman hanging on his arm. If he dined alone it might raise suspicion. And there was something else. He found her cockiness attractive. Challenging. Besides, she wasn’t trying to pick him up. She was trying to hook him up with her friend.

But then she took his arm and said, “Why don’t you take me to El Ajillo with you? No one likes to eat alone.”

In the street, people were going about their business, walking in and out of the hotel or simply waiting. In Cuba, that was what they did. Wait. What was happening between Marisol and him was just one moment in many. Yoselin and the other girl had gone back inside the Sevilla.

She was quite beautiful. And it was just dinner. He met her eyes. There was something tender in them. His stomach quivered. He stepped aside and allowed her into the taxi.

“El Ajillo?” the driver asked.

“Yes. I’ve heard it’s pretty good, no?”

“Señor,” the driver said with authority, “es el mejor. The best in the world. I can promise you, never in your life have you tasted such food.”

Frank leaned back on the seat as the taxi left Prado behind and traveled down the Malecón, Havana’s seaside boulevard. Marisol sat with her face pressed against the window. She seemed sad, absorbed in her own problems, a dark world of lost nights. But he knew nothing of her life.

“So.” He swallowed his fear. “Have you ever been there?”

“Qué va, chico, and how would I pay for it?”

Maybe it had been a mistake. He had misread her eyes. He had to be careful. She could be anybody.

“But tell me,” she said, “how is it in Miami?”

“I live in New York.”

“I would love to go to Miami. They say it’s just like another Habana.”

“Yeah.” Frank laughed. “You could say that.”

She adjusted the thin dress strap that had slipped down her arm and turned back to the road. Frank watched her for a moment. Suddenly she seemed shy, distant. Perhaps it was all a game. Or business. Not all jineteras were professional prostitutes. Something about Marisol seemed tough and innocent at once. He wanted to pull her close, hear her story. But instead he turned away and watched the buildings race past on his left. Dim lights spilled out of open windows, all amber and green. Along the Malecón there were no billboards, no neon, no signs, no crowds, no drive-thrus. Havana was everything New York City was not: the traffic was light, the streets were dark, peaceful. People strolled without hurry. He rolled down the window and breathed in the salty ocean air spiced with refinery fumes and a thousand perfumes of flowers and women and cooking stoves and the life that was Havana. When he exhaled, he released all of New York City, all of Maduros and Pepe and Justo and Filomeno. The tropical night swallowed it whole without so much as a gasp.

“Caballero,” the driver said, “I have the air conditioning for your comfort.”

Frank caught his eyes through the rearview mirror. He could be an informant. A spy. He’d often heard taxi drivers were the eyes and ears of the Castro government.

El Ajillo was a rustic open-air restaurant in the style of a bohío. It had a thatched roof and long wooden tables set under the canopy of a pair of thick almond trees strung with Christmas-style lights. The place was packed.

A conjunto played Chan Chan over the buzz of dinner conversations. Waiters moved between the tables delivering large family-style platters of chicken along with rice and beans, plantains and yucca served from huge clay casseroles. The aroma of the food floated over the restaurant like something sacred. It was a smell without definition, like a fresh rain—a storm—but so much more: exotic and ethereal, yet vaguely familiar.

The maitre’d informed them it would be at least an hour before they could be seated. They nudged their way through the crowd and found a place to stand at the end of the bar.

Marisol sipped her Tropicola and looked casually around the restaurant as if she were trying to recognize someone. “So what do you do in New York?”

It sounded like she was turning on her program. “My brother and I have a restaurant.”

“¿De verdad? What kind, McDonald?”

“No. A real restaurant. Cuban food.” But that was a lie. Justo’s culinary inventions—appetizers of garlic octopus, chorizo and grilled shrimp in sugarcane skewers, entrees of roast quail with a ginger and sherry reduction, lamb steamed in banana leaf with a tart and spicy guava sauce—had nothing to do with Cuba.

“I’d like to go to the McDonald one day and eat a Whopper.”

Frank laughed and took a long sip of his mojito. He loved the simplicity of her wish. But it also made him sad—simple, innocent dreams like those of a child. It was something he saw in himself at times.

Marisol peeked into her glass. “So, in your country, are you very rich?”

His eyes traced the smooth line of her arm. “I wish.”

“I wish,” Marisol said seriously, “that one day I’ll meet someone who will take me away from this place.”

He stirred his drink with the small plastic straw. “Is that what Cuban girls dream of?”

She didn’t look up. She just sipped her drink and made a small gesture with her hand. “That’s the only dream a Cuban girl can have.”

“Does it happen a lot?”

“What?” She threw her head to the side and stared into his eyes. “That they find a foreigner who marries them and takes them away like in a fucking fairy tale? Yes, it happens.” Then she lowered her head and whispered, “To the lucky ones.”

Frank thought she was playing him like a game, but there was something delicate in her manner, like her emotions were made of glass. “Has it happened to someone you know?”

She stared at the ice floating in her Tropicola, the reflections sparkling like tiny stars. “To some friends. And to my sister.” Then, she tossed her head to the side and called the bartender, “Oye, dame un ron con Coca Cola.”

“Where did she go?”

“Who?”

“Your sister.”

“Too far.”

She was dropping this on him like a line. Perhaps that was all it was. Maybe sympathy was her weapon. He reminded himself to be careful. After all, she was a prostitute. Reality was upside down here. This was a place where doctors drove taxis, waiters were rich and a girl’s best chance for a future was to offer herself to a foreigner. Or she could be a government agent. Anything was possible.

“She went to Spain.”

“What part?”

“What part of Spain? Chico, how would I know?” She threw her arms in the air and her lip trembled. “Spain, that’s all I know. She hasn’t written or called since she left almost a year ago. She promised she would arrange for me to come, even if it was just for a visit. But I’ve heard nothing. Nada. ¡Coño!”

“I’m sorry.” She had pulled him in. He wanted to hold her in his arms and have her tell him more, but all he said was, “Do you want to talk about something else? What do you do? I mean when, tú sabes…”

“When I’m not jineteando?” she said with a hint of humor. “I’m waiting to get into the tourism school. I want to get a job in a hotel or a restaurant, somewhere where I can make some real fula. I was studying literature at the University but, chico, you don’t know how useless that career is now. I could just as well study Marxist theory.” She shook her head. “Can you imagine the fools that spent six years studying that mierda? What will they do now? Nada, chico, they’re lost!”

“You don’t have to be so angry.”

She was trembling.

“At least not with me.”

“¿Sabes qué? I don’t have to be here. I don’t have to be with you. I don’t have to have sex with you.”

“Who said anything about sex? You were the one who asked me to take you to dinner, and now you’re arguing with me like I was the cause of all your problems.”

Their eyes met and the corners of her lips turned upwards in the slightest hint of a smile.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly. “I’m new at this. And sometimes I’m not in the mood, tú sabes? I get so sick of foreigners. I get sick of their stories and how they love Cuba. They think everything is perfect here because their vacation is perfect. I hate the looks I get from Cuban men when I’m with a foreigner. Like how the bartender looks at you when I order my drink. Like he needs approval from you.”

“Entonces, why do you do it?”

She made a motion with her hand, the tip of her fingers grouped together, back and forth into her mouth. “I have to eat, no?”

“But—”

“Oye, It’s not like I sleep with everyone. We go out, if I don’t like you, I don’t sleep with you. I’m not like Yoselin. She sleeps with so many guys, one day she’s going to be rich.” She laughed and turned away. “Money’s not everything. Sometimes it’s just about going out and doing something. We all need to escape this nightmare.”

“Sorry, I wasn’t—”

“Ay, Frank.” Her eyes moved quickly about the bar. Then she leaned close to him and whispered, “It’s very unfortunate what Fidel has done to Cuba.”

They were shown to a table under the low branches of an almond tree. Frank ordered a plate of the famous chicken. He kept reminding himself of where he was. His mother’s voice whispered to him, “Beware.” He searched the dining room for a waiter who might resemble Justo, but the place was too busy. He spotted a pair of security men, one by the entrance and one by the kitchen.

A waiter arrived with a large platter of chicken. Frank inspected the unimpressive brown morsels and breathed in the scent. He thought of his youth—cinnamon or cloves and a pleasant memory that wasn’t quite clear. It was just there, slightly beyond his grasp, like a cloud caught in a violent wind.

Marisol reached across the table and touched his hand. “Are you okay?”

He broke from his trance and stared at her dark, tender eyes. A warm, pleasant feeling circled his gut.

The chicken smelled earthy, inviting. He examined its texture, his fingers moving about the mild roughness of the skin. It wasn’t breaded, but it had a thin coat of powder, like brown sugar or coarse spices the color of copper. He closed his eyes and sank his teeth into the meat. The flavor was completely unexpected. It was the ideal balance of sweet and sour without being either. It was tropical and painful and tender.

He took another bite, oblivious of the waiters crisscrossing the dining room filling plates with rice and beans, of the conjunto at the other end of the dining room. He dropped the bone on his plate and glanced at Marisol.

“It’s so good,” he said. “It’s better than sex.”

Marisol eyed him with curiosity.

He paused to analyze the chicken, but it was useless. It was everything, and it was nothing—a complex blend that confused him. It took him away to another time. He was on a beach in Puerto Rico running with Pepe under the broken shade of palm trees, hunting for fallen coconuts. A breeze brought the smell of garlic and fish and charcoal from cooking fires. The ocean made soft swishing sounds with the tide. His father held his mother’s hand as they walked together along the water.

Then time skipped forward to when he was seventeen, excited and afraid. The smell of sandalwood incense mixed with the aftertaste of the joint they’d smoked and a soft hint of musk that came from a place he had never been. Lizzy Fernandez. It was the first time he touched her breast, soft and forbidden. Lizzy. He explored her skin and her muscles, her bones and her hair and the back of her neck, her thighs.

And then there was his father, lying on the bed at MD Anderson, tethered to a machine by thin green tubes and wires. The only sound in the room was the slow suction of the mechanical lung and the sharp rhythmic beep of the heart monitor. He was gaunt, his skin pale like rice paper.

“Frank.” His voice was weak, but deep. “Is that you?”

Frank nodded and took his hand. Filomeno said nothing more. They remained like that for a long while until Frank felt a light tug at his hand followed by the soft remorseful sigh of his father’s last breath.