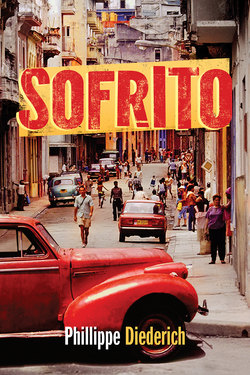

Читать книгу Sofrito - Phillippe Diederich - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

“When I make tostones, I press the plantain so it’s flat. Then I fry it in oil, but I allow a small bit in the center to remain uncooked so they won’t get too dry. It also gives them a more pleasant texture.”

—María Ramírez de la Garza

cook at La Tropical restaurant on Calle Ocho, The Miami Herald, 1995.

The city of Havana was covered in a thin haze. Everything was gray. The buildings, the street, the cars, the sidewalk, even the people carried an overcast texture that was drab and without color. But slowly, hues introduced themselves in a yellow dress, a flower print shirt, a red ‘57 Chevy convertible decorated with pink and white balloons parked in front of El Palacio de los Matrimonios.

Frank took Marisol’s hand. They walked down Prado’s center esplanades to the Malecón where a melancholy ocean shifted in a dark, metallic monochrome. Fishermen casting their lines sat on inner tubes that bobbed up and down with the tide of silver waves. East of the city, a long streak of dark smoke rose from the refinery and stretched like a shoelace across the sky.

The avenue was flanked by a long row of faded pastel buildings, their tattered facades held in place by skeletons of two-by-fours and scaffoldings that looked as old and delicate as the buildings. And behind them, more buildings rose, each a tone grayer than the next, their own forgotten histories buried deep within apartments that were separated into rooms, which were divided into smaller rooms by makeshift walls of wood and cloth sheets.

They crossed the avenue and made their way into the grid of streets and buildings that rose three, five, sometimes eight stories high, their facades covered in smog and soot from bad gasoline and dust from the crumbling of the city. The rooftops were littered with television antennas and small homemade satellite dishes put together from recycled oilcans and wire mesh. The balconies were dressed in drying laundry and potted plants that desperately reached out for the Caribbean sun. Women leaned over windows, smoking Popular cigarettes. A man rode past with a basket of fruit on the back of his bicycle followed by an echo of calls, “¿Tienes mango?”

Shirtless men leaned against walls, door stoops, and over balconies, admiring the women who strutted past, their buttocks swinging to the rhythm of a Pérez Prado mambo.

“Oye, mi amor,” they called, “ven acá que tengo algo pa’ ti. ¡Candela!”

On the side of the street, a ‘53 Buick rested on blocks. A couple of shirtless men prodded under its hood. A few doors down, a group of women were gathered at the entrance of a building trading gossip. Across the street, a pair of old men sat sideways on a doorstep sharing a drink from a plastic bottle that had been filled and refilled with chispa.

Frank absorbed the details. In every conversation he longed to hear his father, his voice rising above another, arguing. He wondered if these same streets had been the genesis of Filomeno’s volatile temper. His father had been a man of few words, but when anyone mentioned Cuba, he came alive.

Like that afternoon when they’d visited one of Rosa’s friends in Pearland. Frank, Pepe, and their friend Jorge were watching television. In the background they could hear the voices of the grown-ups rising in argument. They heard, “Cuba,” and someone yelled, “Fidel,” and then, “Cuba,” again. The next thing Filomeno was shouting, “Cuba, where the hell is it now?”

They watched him storm out of the house like an angry teenager. And Jorge, who was younger than Frank, said, “Oye, what’s wrong with your papá?”

It was as if Filomeno did not want to be reminded that somewhere southeast of Houston, just past Miami, there was a place he once called home. He seemed angry at Cuba just because it existed.

Rosa could be relentless. She wielded that country like a knife. It always led to the kind of violence that prompted Frank and Pepe to escape the house or shut themselves in their bedroom. But deep down, with his head buried in a pillow, Frank found the arguments a relief from the silence and indifference that otherwise permeated their lives. Now, as he walked the streets of Centro Habana, he could not imagine his father here. He could not see him on the street corner or leaning over a balcony or waving at a relative or fixing his old Chevy or smoking a cigar or being Cuban—not like this. Filomeno had lived as far away from Cuba as the moon.

At the crossing of Calle Lealtad and Concordia, the street was closed off to traffic by rusted yellow barricades where Pioneros—elementary students—in their burgundy and white uniforms skipped rope and sang rhymes.

The sun began to find its way out of the clouds. The haziness subsided and the day became progressively warmer. The blue of the Caribbean sky was finally showing in the distance towards the ocean.

At the intersection with Calle Espada, Marisol stopped. “Which one is it?”

“Number forty-five. It’s a gray building.” But there were no numbers. And all four buildings on the corner were gray.

Marisol looked up and down the street. “Who are we looking for?”

“Eusebio. And Esperanza.”

Marisol stepped forward. “Eusebio! Esperanza!” The people on the street went about their business without raising an eyebrow. She called again, “Eusebiooo! Esperanzaaa!”

“No está.” A little boy poked his head out from the balcony of a building across the street.

“Eusebio?” Frank called.

“Eusebio doesn’t live here anymore.”

“What about Esperanza?”

“She went out. To the choppin.”

Frank glanced at Marisol. “And you, niño?” he asked. “Who are you?”

“I’m Pedrito. The son of Capitán, the one who is married to Esperanza.”

“Do you know where Eusebio lives?”

“Yes.”

Frank waited, but when Pedrito said nothing, he asked, “Where does he live now?”

“In Vedado.”

Frank shook his head. “Do you know where in Vedado?”

“No. I’m only a little boy.”

“¡Compañera!” A pair of skinny teenagers in baggy shorts and T-shirts with opulent Nike logos approached them from the other side of the street.

The one with the bleached, spiked hair moved his shoulders as he spoke, his hands gesturing below his waist. His eyes skipped from Marisol to Frank and back. “You’re looking for Eusebio? We used to be neighbors.”

“Do you know where he lives?” she asked.

“Claro, en Vedado. We can take you there. We were just now talking about Eusebio and—”

“How far is it?” she interrupted.

“Coño, not far. We can take Orlando’s Moskvitch, but we’ll need a little money to help with the gasoline.”

“Ah.” Marisol shifted her weight and her eyes narrowed. “Y dime, what were you going to do if we hadn’t shown up?”

“Well.” He pulled a cigarette from behind his ear, glanced at it and gestured with it as he spoke. “I was just telling Orlando here how we hadn’t caught sight of Eusebio in so many weeks and that it would be nice to pay him a little visit. ¿Sabes? And Orlando was saying how we needed to figure out something to procure some gasoline. And then we hear your pretty voice calling for him.”

“Divina providencia.” Orlando, the one with the dark skin and a trim afro, leaned forward and lit his friend’s cigarette.

“How much?” Marisol asked.

“I don’t know.” The other glanced at Orlando. “¿Cinco, seis dólares?”

“Okay,” Frank interrupted, “vamos, let’s go.”

“Coño.” The one with the bleached hair offered Frank his hand.“¿Español?”

“No, Americano. Let’s go. Where’s the car?”

“¡Coño!” He glanced at Orlando whose eyes had also lit up at the word Americano. Then he raised his hand and bought it down for Frank to take again. “Miami?”

“New York.”

“¡Coño! New Yor’, I’m Michi and this is Orlando. Whatever you require during your stay in La Habana we can get it for you: rum, cigars, girls—”

“Let’s go.”

“Coño, el Yuma’s in a hurry.” Michi put the cigarette between his lips and led them around the corner where a square blue automobile covered in gray patches of primer was parked. But when Orlando turned the key nothing happened.

Michi jumped out and got to work under the hood. “¡Dale!”

Orlando tried again and the car exploded with a loud backfire. Michi hopped back in, and they were off, leaving behind a thick cloud of black smoke.

“Inferior gasoline,” Michi complained. “Entonces, Frank, you think Clinton will lift the bloqueo before he leaves office?”

“The embargo? How would I know?”

“Never mind, it’s of no consequence. We can get what we want now.” Michi counted the items with his skinny fingers. “Nike, Levi’s, CNN, Marlboros, Heineken.”

“Don’t tell me—you have family in Miami.”

“No.” Michi patted Orlando on the back. “We work. We’re a team. You see, Cuba is not like the United States. Here, you can’t work a job and expect to make a decent living.”

“Here you have to invent your own living.” Orlando glanced at Marisol through the rearview mirror. “Isn’t that so?”

“Óyeme, don’t bring me into this. What you two do is your business.”

“Coño,” Michi said. “He means you’re Cuban, hay que resolver, no?”

Michi studied the road to gauge their location and gave Orlando directions. They drove in silence for a few blocks. Then Michi leaned forward and tapped Orlando on the shoulder. “It’s here.” He pointed at a small blue and white house with a narrow front porch.

“Are you sure?” Frank said.

“Coño.” Michi frowned. “Of course.”

Michi knocked on the door. A brindle pit bull barked at them from the roof of the house. “Huracán,” he called and glanced at Frank. “That is one mean dog.”

“But only to other dogs,” Orlando added.

A pretty blonde wearing tight red shorts and a Cubanacan T-shirt opened the door.

“Hola, Guajira,” Michi said. “Is Eusebio home?”

Guajira rubbed her eyes. “’Pérame.” Then she closed the door.

Michi turned to Frank and smiled. “And you didn’t believe me.”

When the door opened again, a man who was a darker, heavier version of Justo studied the group.

“Eusebio.” Michi offered his hand, but when Eusebio didn’t take it, he made a self-conscious gesture and dropped it at his side. “We brought you some friends.”

Eusebio’s drowsy eyes inspected the group and landed back on Michi. “¿Y? Who are they?”

“Frank and Marisol. They were calling for you at your sister’s house on Concordia.”

Frank offered his hand. “I’m Frank Delgado, a friend of Justo’s in New York.”

Eusebio’s eyes grew, and his lips parted in a large white smile. “I don’t believe it!” He embraced Frank. “What a pleasure. I had no idea. What a terrific surprise, but tell me something, Frank.” Eusebio glanced over at Michi and Orlando. “How did you hook up with these two comemierdas?”

“Óyeme, Eusebio,” Michi complained, “por favor. We were doing them a favor.”

“Here.” Frank dug into his pocket, counted out five dollars and offered them to Michi.

Eusebio frowned. “¿Qué fue?”

“Coño, Eusebio. We need it for gas. The Moskvitch is almost out.”

“Michi, he’s my brother, por el amor de Dios.”

“I didn’t know.” Michi glanced at Frank, then at Eusebio. “But, coño, there seems to be a minor discrepancy in the color, no?”

“I tell you he’s my brother. What else do you want, a fucking birth certificate?”

“It’s okay.” Frank pushed the money into Michi’s hand.

“And this mulatica,” Eusebio stared past Frank at Marisol. “Is she with you?”

“She’s with your brother,” Michi smiled. “Candela, no?”

Eusebio buttoned his shirt. “Come in then. We’ll have some coffee. You drink café, no?”

Eusebio led the way into the house with his arm around Frank’s shoulder. They walked through the living room. A bulky Panasonic television dominated the room like a special prize. On the wall was a poster of Fidel Castro in the midst of a fiery speech.

“Guajira, coffee for six, mujer.” Eusebio turned to Frank. “We better go out to the patio, it’s too hot to sit inside.”

They found places around a plastic table under the shade of a large ceiba tree. A gentle breeze stirred the smell of jasmine.

“Coño, Frank, it’s such a pleasure to meet you,” Eusebio said. “Tell me, how is my brother? And Pepe, right?”

“Everybody’s fine. Working all the time. You know Justo’s married.”

“I know, I know. With a Dominican, no?” Eusebio leaned forward and frowned.

“Yes. She’s a wonderful woman.”

“Good for him.” Then he glanced at Michi, rubbed his nose and turned to Marisol. “And you, my love, how do you fit into all this?”

Marisol shrugged and crossed her legs. “Nothing. We met last night. I’m just helping him get around.”

Eusebio laughed and clapped his hands. “You’re a tourist guide, qué bien. I like that.”

Frank found his tone intrusive. He placed his hand on Marisol’s leg and changed the subject. “So, this is your new house?”

“Yes. I am finally coming into some modest money. You know, with Esperanza getting married and the twins on the way, I got together with Capitán and we, I, acquired this place so they could have the apartment on Concordia to themselves.”

Guajira appeared from the kitchen carrying a tray with tiny blue coffee cups.

“And this beauty here is Yemanki.” Eusebio pulled her by the hip and sat her on his lap. “But we call her Guajira because she’s from Cabeza, in Pinar Del Río. And besides, Yemanki, what an ugly name, no? Poor woman, another victim of Cuba’s generation Y.”

A green parrot in a large wire cage squawked. Eusebio turned to Michi. “And you two?”

“Nothing, Eusebio, we just wanted to see you. Since you moved to Vedado we don’t see as much of you as we used to. You should stop by the old neighborhood once in a while.”

“I stop by all the time when I visit Esperanza and Capitán—and that little devil Pedrito.”

“Well.” Michi turned uncomfortably. “I suppose we figured we could kill two birds with—”

“You wanted the money,” Eusebio interrupted.

“Coño, Eusebio.” Michi waved. “But we wanted to visit you too. How was I to know he was—”

“Bueno.” Orlando drained his coffee and stood. “I think it’s time, no?”

“Coño, Eusebio.” Michi pressed his hands against his chest, “I didn’t mean any disrespect.”

“Next time just say it like it is.”

After Michi and Orlando left, Eusebio leaned back on his chair and sighed. “Those two never stop. I know it’s not easy, pero, coño, one must have a little dignity.” Then he smiled at Marisol, “Coño, But what a beautiful mulata you have here, Frank. For real.”

Frank smiled. Marisol looked away.

Eusebio turned on his chair and drank what coffee remained in his cup. “So, how long are you here for?”

“Just a week. I leave on Sunday.”

“Where are you staying?”

“The Sevilla.”

“Coño, the Sevilla. It’s a great place. But next time you must stay here in our house,” Eusebio declared. “La Habana has a housing shortage, but we’re lucky we have plenty of room for guests.”

“Gracias, that’s very hospitable, Eusebio.”

“Coño, you’re family.” He spread his arms. “I would not expect any less from you if I was to visit New York. Us Cubans, we prefer the warmth of a home and family to the coldness of a hotel, no matter how luxurious.” Eusebio leaned forward and frowned, “But Dominican? Coño, are there no good Cuban women in New York? I mean, Dominican?”

“If you met Amarylis you’d understand.”

They shared a brief silence. Then Eusebio clapped his hands. “Coño, you’re right, Frank. And besides, the Dominican Republic is like a sister country, no? Máximo Gómez helped us fight for independence. He’s buried right over there in the cementerio Colón.” Then he paused and glanced at his empty cup. “And you, are you married?”

“No.” Frank laughed. “I was close, but we broke up right at Christmas.”

“Was she Cuban?”

“No, American.”

Eusebio waved his index finger. “That’s good, Frank. But you know, a Cuban man needs a Cuban woman. With American women it’s just not the same, eh?”

Frank smiled and glanced at Marisol. It was what his mother always said. But he had never met a Cuban woman until now.

He leaned forward and rested his arms on the table. “Eusebio, I need to speak with you. In private.”

Eusebio’s lazy grin faded, and his brow dropped over his round dark eyes. He dug into his shorts pocket and handed Guajira a handful of dollar bills. “Guajira, go down to the choppin and get some beer.” Then he turned to Frank. “Or do you prefer rum?”

“Beer’s fine. Thanks. Con este calor.”

“You’re right. It will be good with this heat.” He turned back to Guajira. “Get some beer, de la Cristal, and whatever you need for lunch.” And to Frank, “You’re staying for lunch right?”

“Sure, thanks.”

“Okay, get whatever you need for lunch,” he said. “If you want ham, Montecristi stopped by yesterday and said Lázaro’s brother butchered a pig. You can stop by his house and see what he has.”

“Sí, mi amor.”

“Marisol,” Eusebio added, “why don’t you go with Guajira so Frank and I can have a little man to man, no?”

Frank followed Eusebio to the parrot’s cage. On the roof, the dog barked after Guajira and Marisol walking down the street.

“Listen, Eusebio,” Frank stepped away from the cage. “Justo, Pepe and I…we have a restaurant in New York.”

“Of course. Maduros, no?”

“That’s right.” He sighed and stared at the ground. “We’re in trouble. We’re being pressured by the bank. We might have to close the restaurant.”

“That’s a shame.”

“Eusebio, the reason I’m here is to ask for your help.”

“Coño, my help? But I am only a poor waiter. I don’t have any money.” He tore a leaf off a bamboo plant and held it between the bars of the cage.

Frank watched the bird. He thought of the restaurant, of Justo’s blood flowing down his arm, of his mother looking around the empty dining room, too embarrassed to say anything, of the mountain of unpaid bills on his desk, his constant arguing with suppliers and vendors, begging them for time and credit. Maduros was all they had. It kept them together.

“It’s not money,” he said, and his eyes took a dance around the yard, skipping from the cage to a green lizard crawling on a wall to the empty little blue cups on the table.

“Coño, Frank, what is it then?”

Frank focused on Eusebio’s eyes, but he couldn’t hold the stare. “The recipe for the chicken.”

Eusebio stared at him for a moment. Then he laughed. “What, of El Ajillo?”

Frank lowered his head and glanced at his shoes. A torrent of shame came over him like a child caught in a terrible lie.

“Coño, you’re crazy. Why don’t you just ask me to murder El Caballo.” Eusebio waved his hands in the air. “Frank, my friend, you’re asking for something that is absolutely impossible.”

“What about Quesada?”

“Quesada who?”

“The owner.”

“The State owns the restaurant.”

“But Nestor Quesada was the original owner. He knows the recipe. Maybe—”

“I don’t know any Nestor Quesada.”

“He’s my father’s uncle.”

“Frank—”

“It’s his recipe.”

“There is no Quesada at El Ajillo, Frank. No. This is impossible.”

“But Justo said you could get it for us.”

“Justo doesn’t know shit. It’s stealing. It’s illegal. And you’re not talking of just any recipe.”

“But it belongs to my family—”

“No.” Eusebio waved violently. “You sound like the capitalists with the Foundation in Miami, living the good life while they wait for things to change here, like fucking vultures. What the exiles left behind, they abandoned. I’m not going there with you, Frank.”

“But Eusebio—”

“If this man Quesada left, he gave it up.”

“He didn’t leave,” Frank said. “He stayed. He trusted Fidel. But he was tortured.”

Eusebio stared at Frank, his dark eyes wide, angry. “You know that for a fact?”

“No.” Frank said quickly. “No, but my mother implied it. How else would the State get his recipe and reopen the restaurant?”

“Exile propaganda.” Eusebio waved.

“But what about Maduros?”

“What about it?”

“We need the recipe—”

“No, Frank. It’s impossible.”

“Por favor.” Frank pressed the palms of his hands together as if he were praying. “We’re going to lose it. We’ll be left with nothing.”

“We should not even be talking about this.” Eusebio looked nervously around the garden and in the direction of his neighbor’s house.

“It’s our only chance.”

“No.” Eusebio placed a hand on Frank’s shoulder. “That recipe is so well guarded, they say only one person knows the full recipe. And he’s with the State.”

“We can pay.”

Eusebio laughed. “Believe me. There’s not enough money in your Fort Knox. I had to pay almost two thousand dollars just to get a job there. It’s the busiest restaurant in La Habana. I bring home sixty, sometimes eighty dollars a week. Coño, Frank, in Cuba, that is a rich man’s salary. I don’t want to jeopardize my job. And believe me, neither will anyone else at El Ajillo. Besides, they would also risk going to prison and ending up like your uncle.”

“There has to be a way.”

“No, no. Absolutely not.”

Deep down he had known it would be like this. And in a strange way he felt relieved. His desperation dissipated into the pale sky. Maduros would close and he would be condemned to live a life like his father’s.

“There’s Huracán baking now. Las mujeres must be back with the beer and perhaps a nice ham steak.” Eusebio slapped him on the back and rubbed the palms of his hands together.

But Frank was compelled to push it one last time. “Just tell me you’ll look into it.”

They could hear the women in the kitchen, opening the beer and talking of summers in Pinar Del Río.

“I’m sorry, Frank,” Eusebio said with finality. Then he turned to meet Guajira and Marisol who were coming out on the patio with a beer in each hand. “Por fín, something to cool us off.”

They raised their beers in a toast.

“¡A la familia!”