Читать книгу Domestica - Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo - Страница 10

Оглавление1

New World Domestic Order

Contemplating a day in Los Angeles without the labor of Latino immigrants taxes the imagination, for an array of consumer products and services would disappear (poof!) or become prohibitively expensive. Think about it. When you arrive at many a Southern California hotel or restaurant, you are likely to be first greeted by a Latino car valet. The janitors, cooks, busboys, painters, carpet cleaners, and landscape workers who keep the office buildings, restaurants, and malls running are also likely to be Mexican or Central American immigrants, as are many of those who work behind the scenes in dry cleaners, convalescent homes, hospitals, resorts, and apartment complexes. Both figuratively and literally, the work performed by Latino and Latina immigrants gives Los Angeles much of its famed gloss. Along the boulevards, at car washes promising “100% hand wash” for prices as low as $4.99, teams of Latino workers furiously scrub, wipe, and polish automobiles. Supermarket shelves boast bags of “prewashed” mesclun or baby greens (sometimes labeled “Euro salad”), thanks to the efforts of the Latino immigrants who wash and package the greens. (In addition, nail parlors adorn almost every corner mini-mall, offering the promise of emphasized femininity for $10 or $12, thanks largely to the work of Korean immigrant women.) Only twenty years ago, these relatively inexpensive consumer services and products were not nearly as widely available as they are today. The Los Angeles economy, landscape, and lifestyle have been transformed in ways that rely on low-wage, Latino immigrant labor.

The proliferation of such labor-intensive services, coupled with inflated real estate values and booming mutual funds portfolios, has given many people the illusion of affluence and socioeconomic mobility. When Angelenos, accustomed to employing a full-time nanny/housekeeper for about $150 or $200 a week, move to Seattle or Durham, they are startled to discover how “the cost of living that way” quickly escalates. Only then do they realize the extent to which their affluent lifestyle and smoothly running household depended on one Latina immigrant woman.

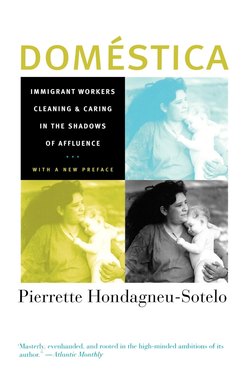

This book focuses on the Mexican and Central American immigrant women who work as nanny/housekeepers and housecleaners in Los Angeles, as well as the women who employ them. Who could have foreseen that at the dawn of the twenty-first century, paid domestic work would be a growth occupation? Only a few decades ago, observers confidently predicted that this occupation would soon become obsolete, replaced by labor-saving household devices such as automatic dishwashers, disposable diapers, and microwave ovens, and by consumer goods and services purchased outside of the home, such as fast food and dry cleaning.1 Instead, paid domestic work has expanded. Why?

THE GROWTH OF DOMESTIC WORK

The increased employment of women, especially of married women with children, is usually what comes to mind when people explain the proliferation of private nannies, housekeepers, and housecleaners. As women have gone off to work, men have not picked up the slack at home. Grandmothers are also working, or no longer live nearby; and given the relative scarcity of child care centers in the United States, especially those that will accept infants and toddlers not yet toilet trained, working families of sufficient means often choose to pay someone to come in to take care of their homes and their children.

Even when conveniently located day care centers are available, many middle-class Americans are deeply prejudiced against them, perceiving them as offering cold, institutional, second-class child care.2 For various reasons, middle-class families headed by two working parents prefer the convenience, flexibility and privilege of having someone care for their children in their home. With this arrangement, parents don't have to dread their harried early-morning preparations before rushing to day care, the children don't seem to catch as many illnesses, and parents aren't likely to be fined by the care provider when they work late or get stuck in traffic. As the educational sociologist Julia Wrigley has shown in research conducted in New York City and Los Angeles, with a private caregiver in the home, parents feel they gain control and flexibility, while their children receive more attention.3 Wrigley also makes clear that when they hire a Caribbean or Latina woman as their private employee, in either a live-in or live-out arrangement, they typically gain something else: an employee who does two jobs for the price of one, both looking after the children as a nanny and undertaking daily housekeeping duties. I use the term “nanny/housekeeper” to refer to the individual performing this dual job.

Meanwhile, more people are working and they are working longer hours. Even individuals without young children feel overwhelmed by the much-bemoaned “time squeeze,” which makes it more difficult to find time for both daily domestic duties and leisure. At workplaces around the nation, women and men alike are pressured by new technology, their own desires for consumer goods, national anxieties over global competition, and exhortations from employers and co-workers to work overtime.4 As free time shrinks, people who can afford it seek relief by paying a housecleaner to attend to domestic grit and grime once every week or two. Increasing numbers of Americans thus purchase from nanny/housekeepers and housecleaners the work once performed by wives and mothers.

Of course, not everyone brings equal resources to bear on these problems. In fact, growing income inequality has contributed significantly to the expansion of paid domestic work. The mid-twentieth-century trend in the United States toward less income inequality, as many researchers and commentators have remarked, was shortlived. In the years immediately after World War II, a strong economy (based on an increasing number of well-paying unionized jobs in factories), together with growing mass consumption and federal investment in education, housing, and public welfare, allowed many Americans to join an expanding middle class. This upward trend halted in the early 1970s, when deindustrialization, the oil crisis, national inflation, the end of the Vietnam War, and shifts in global trade began to restructure the U.S. economy. Gaps in the occupational structure widened. The college educated began to enjoy greater opportunities in the professions and in corporate and high-technology sectors, while poorly educated workers found their manufacturing jobs downgraded—if they found them at all, as many were shipped overseas. During the 1980s and 1990s, income polarization in the United States intensified, setting the stage for further expansion of paid domestic work.

Specific location is important to this analysis, for the income distribution in some cities is more inequitable than in others, and greater inequality, as an important study directed by UCLA sociologist Ruth Milkman has shown, tends to generate greater concentrations of paid domestic work. When the researchers compared cities around the nation, the Los Angeles-Long Beach metropolitan area emerged as the nation's leader in these jobs (measured by the proportion of all employed women in paid domestic work), followed by Miami-Hialeah, Houston, and New York City.5

Los Angeles' dubious distinction is not hard to explain. All of the top-ranked cities in paid domestic work have large concentrations of Latina or Caribbean immigrant women, and Los Angeles remains the number-one destination for Mexicans, Salvadorans, and Guatemalans coming to the United States, most of whom join the ranks of the working poor. Moreover, Los Angeles is a city where capital concentrates. It is a dynamic economic center for Pacific Rim trade and finance—what Saskia Sassen, a leading theorist of globalization, immigration, and transnational capital mobility, refers to as a “global city.” Global cities serve as regional “command posts” that aid in integrating the new expansive global economy. Though Los Angeles lacks the financial power of New York or London, it has a large, diversified economy, supported both by manufacturing and by the capital-intensive entertainment industry. The upshot? Los Angeles is home to many people with highly paid jobs. As Southern California businesses bounced back from the recession of the early 1990s, many already handsomely paid individuals suddenly found themselves flush with unanticipated dividends, bonuses, and stock options.6 And as Sassen reminds us, globalization's high-end jobs breed low-paying jobs.7

Many people employed in business and finance, and in the hightech and the entertainment sectors, are high-salaried lawyers, bankers, accountants, marketing specialists, consultants, agents, and entrepreneurs. The way they live their lives, requiring many services and consuming many products, generates other high-end occupations linked to gentrification (creating jobs for real estate agents, therapists, personal trainers, designers, celebrity chefs, etc.), all of which in turn rely on various kinds of daily servicing that low-wage workers provide. For the masses of affluent professionals and corporate managers in Los Angeles, relying on Latino immigrant workers has become almost a social obligation. After relocating from the Midwest to Southern California, a new neighbor, the homemaker wife of an engineer, expressed her embarrassment at not hiring a gardener. It's easy to see why she felt abashed. In New York, the quintessential service occupation is dog walking; in Los Angeles' suburban landscape, gardeners and domestic workers proliferate. And in fact, as Roger Waldinger's analysis of census data shows, twice as many gardeners and domestic workers were working in Los Angeles in 1990 as in 198o.8 Mexicans, Salvadorans, and Guatemalans perform these bottom-rung, low-wage jobs; and by 1990 those three groups, numbering about 2 million, made up more than half of the adults who had immigrated to Los Angeles since 1965.9 Hundreds of thousands of Mexican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan women sought employment in Los Angeles during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s,10 often without papers but in search of better futures for themselves and for their families. For many of them, the best job opportunity was in paid domestic work.

Mexican women have always lived in Los Angeles—indeed, Los Angeles was Mexico until 1848—but their rates of migration to the United States were momentarily dampened by the Bracero Program, a government-operated temporary contract labor program that recruited Mexican men to work in western agriculture between 1942 and 1964. During the Bracero Program, nearly 5 million contracts were authorized. Beginning in the 1970s, family reunification legislation allowed many former bracero workers to legally bring their wives and families from Mexico. Immigration accelerated, and by 1990 there were 7 million Mexican immigrants in the United States, concentrated most highly in Southern California. Structural changes in the economies of both Mexico and the United States also significantly affected this dynamic. Mexico's economic crisis of the 1980s propelled many married women with small children into the labor force, and with the maturation of transnational informational social networks—and especially the development of exclusive women's networks—it wasn't long before many Mexican women learned about U.S. employers eager to hire them in factories, in hotels, and in private homes.11

Unlike Mexicans, Central Americans have relatively new roots in Los Angeles. The Salvadoran civil war (1979–92) and the even longer-running conflicts in Guatemala (military campaigns supported by U.S. government aid) drove hundreds of thousands of Central Americans to the United States during the 1980s. Almost overnight, Los Angeles became a second capital city for both Salvadorans and Guatemalans. Estimates of this population, many of whose members cannot speak English and remain undocumented (and hence officially undercounted), vary wildly The 1990 census counted 159,000 Guatemalans and 302,000 Salvadorans in the Los Angeles region, but community leaders believe that by 1994, the number of Salvadorans in Los Angeles alone had reached 500,000.12 Central Americans came to the United States fleeing war, political persecution, and deteriorating economic conditions; and though the political violence had diminished by the mid-1990s, few were making plans to permanently return to their old homes.13 There have been numerous careful case studies of Central American communities in the United States; among their most stunning findings is that wherever Central American women have gone in the United States, including San Francisco, Long Island, Washington, D.C., Houston, and Los Angeles, they predominate in private domestic jobs.14

The growing concentration of Central American and Mexican immigrant women in Los Angeles and their entry into domestic service came on the heels of local African American women's exodus from domestic work. The supply of new immigrant workers has helped fuel a demand that, as noted above, was already growing. That is, the increasing number of Latina immigrants searching for work in California, particularly in Los Angeles, has pushed down wages and made modestly priced domestic services more widely available. This process is not lost on the women who do the work. Today, Latina domestic workers routinely complain to one another that newly arrived women from Mexico and Central America are undercutting the rates for cleaning and child care.

As a result, demand is no longer confined to elite enclaves but instead spans a wider range of class and geography in Southern California. While most employers of paid domestic workers in Los Angeles are white, college-educated, middle-class or upper-middle-class suburban residents with some connection to the professions or the business world, employers now also include apartment dwellers with modest incomes, single mothers, college students, and elderly people living on fixed incomes.15 They live in tiny bungalows and condominiums, not just sprawling houses. They include immigrant entrepreneurs and even immigrant workers. In contemporary Los Angeles, factory workers living in the Latino working-class neighborhoods can and do hire Latino gardeners to mow their lawns, and a few also sometimes hire in-home nanny/housekeepers as well. In fact, some Latina nanny/housekeepers pay other Latina immigrants—usually much older or much younger, newly arrived women—to do in-home child care, cooking, and cleaning, while they themselves go off to care for the children and homes of the more wealthy.

DOMESTIC WORK VERSUS EMPLOYMENT

Paid domestic work is distinctive not in being the worst job of all but in being regarded as something other than employment. Its peculiar status is revealed in many occupational practices, as later chapters will show, and in off-the-cuff statements made by both employers and employees. “Maria was with me for eight years,” a retired teacher told me, “and then she left and got a real job.” Similarly, many women who do this work remain reluctant to embrace it as work because of the stigma associated with it. This is especially true of women who previously held higher social status. One Mexican woman, formerly a secretary in a Mexican embassy, referred to her five-day-a-week nanny/housekeeper job as her “hobby.”

As the sociologist Mary Romero and others who have studied paid domestic work have noted, this occupation is often not recognized as employment because it takes place in a private home.16 Unlike factories or offices, the home serves as the site of family and leisure activities, seen as by their nature antithetical to work. Moreover, the tasks that domestic workers do—cleaning, cooking, and caring for children—are associated with women's “natural” expressions of love for their families. Although Catharine E. Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe in the late nineteenth century, like feminist scholars more recently, sought to valorize these domestic activities (in both their paid and unpaid forms) as “real work,” these efforts past and present have had little effect in the larger culture.17 House-cleaning is typically only visible when it is not performed. The work of wives and mothers is not seen as real work; and when it becomes paid, it is accorded even less regard and respect.

Another important factor that prevents paid domestic work from being recognized as real work is its personal, idiosyncratic nature, especially when it involves the daily care of children or the elderly. Drawing on her examination of elder care workers, the public policy analyst Deborah Stone argues that caring work is inherently relational, involving not only routine bodily care, such as bathing and feeding, but also attachment, affiliation, intimate knowledge, patience, and even favoritism. Talking and listening, Stones shows, are instrumental to effective care. Her observation certainly applies to private child care work, as parents want someone who will really “care about” and show preference for their children; yet such personal engagement remains antithetical to how we think about much employment, which, as Stone reminds us, we tend to view on the model of manufacturing.18 Standardization, and frameworks of efficiency and productivity that rely on simplistic notions of labor inputs and product outputs, simply is irrelevant to paid domestic work, especially when the job encompasses taking care of children as well as cleaning. Since we are accustomed to defining employment as that which does not involve emotions and demonstrations of affective preference, the work of nannies and baby-sitters never quite gains legitimacy.

In part because of the idiosyncratic and emotional nature of caring work, and in part because of the contradictory nature of American culture, employers are equally reluctant to view themselves as employers. This, I believe, has very serious consequences for the occupation. When well-meaning employers, who wish to voice their gratitude, say, “She's not just an employee, she's like one of the family,” they are in effect absolving themselves of their responsibilities—not for any nefarious reason but because they themselves are confused by domestic work arrangements. Even as they enjoy the attendant privilege and status, many Americans remain profoundly ambivalent about positioning themselves as employers of domestic workers. These arrangements, after all, are often likened to master-servant relations drawn out of premodern feudalism and slavery, making for a certain amount of tension with the strong U.S. rhetoric of democracy and egalitarianism.19 Consequently, some employers feel embarrassed, uncomfortable, even guilty.

Maternalism, once so widely observed among female employers of private domestic workers, is now largely absent from the occupation; its remnants can be found primarily among older homemakers. When employers give used clothing and household items to their employees, or offer them unsolicited advice, help, or guidance, they may be acting, many observers have noted, manipulatively.20 Such gestures encourage the domestic employees to work harder and longer, and simultaneously allow employers to experience personal recognition and validation of themselves as kind, superior, and altruistic. Maternalism is thus an important mechanism of employer power.

Today, however, a new sterility prevails in employer-employee relations in paid domestic work. For various reasons—including the pace of life that harries women with both career and family responsibilities, as well as their general discomfort with domestic servitude—most employers do not act maternalistically toward their domestic workers. In fact, many of them go to great lengths to minimize personal interactions with their nanny/housekeeper and housecleaners. At the same time, the Latina immigrants who work for them—especially the women who look after their employers' children—crave personal contact. They want social recognition and appreciation for who they are and what they do, but they don't often get it from their employers. In chapter 7, I argue that while maternalism serves as a mechanism of power that reinscribes some of the more distressing aspects of racial and class inequality between and among women, the distant employer-employee relations prevalent today do more to exacerbate inequality by denying domestic workers even modest forms of social recognition, dignity, and emotional sustenance. As we will see, personalism, achieved by exchanging private confidences and by recognizing domestic workers as individuals with their own concerns outside of their jobs, partially addresses the problem of social annihilation experienced by Latina domestic workers, offering a tenuous, discursive amelioration of these glaring inequalities.

Ironically, many employers are enormously appreciative of what their Latina domestic workers do for them, but they are more likely to declare these feelings to others than to the women who actually do the work. In informal conversation, they often gush enthusiastically about Latina nanny/housekeepers who care for homes and children, expressing a deep appreciation (or a rationalization?) that one almost never hears from someone speaking about his or her spouse. You might hear someone say, “I don't know what I would do without her,” “She's perfect!” or “She's far better with the kids than I am!”; but such sentiments are rarely communicated directly to the employees.

The employers I interviewed did not dwell too much on their status as employers of nanny/housekeepers or housecleaners. They usually identified first and foremost with their occupations and families, with their positions as accountants or teachers, wives or mothers. Like the privilege of whiteness in U.S. society, the privilege of employing a domestic worker is barely noticed by those who have it. While they obviously did not deny that they pay someone to clean their home and care for their children, they tended to approach these arrangements not as employers, with a particular set of obligations and responsibilities, but as consumers.

For their part, the women who do the work are well aware of the low status and stigma attached to paid domestic work. None of the Latina immigrants I interviewed had aspired to the job, none want their daughters to do it, and the younger ones hope to leave the occupation altogether in a few years. They do take pride in their work, and they are extremely proud of what their earnings enable them to accomplish for their families. Yet they are not proud to be domestic workers, and this self-distancing from their occupational status makes it more difficult to see paid domestic work as a real job.

Moreover, scarcely anyone, employer or employee, knows that labor regulations govern paid domestic work. Lawyers that I interviewed told me that even adjudicators and judges in the California Labor Commissioner's Office, where one might go to settle wage disputes, had expressed surprise when informed that labor laws protected housecleaners or nanny/housekeepers working in private homes. This problem of paid domestic work not being accepted as employment is compounded by the subordination by race and immigrant status of the women who do the job.

GLOBALIZATION, IMMIGRATION, AND THE

RACIALIZATION OF PAID DOMESTIC WORK

Particular regional formations have historically characterized the racialization of paid domestic work in the United States. Relationships between domestic employees and employers have always been imbued with racial meanings: white “masters and mistresses” have been cast as pure and superior, and “maids and servants,” drawn from specific racial-ethnic groups (varying by region), have been cast as dirty and socially inferior. The occupational racialization we see now in Los Angeles or New York City continues this American legacy, but it also draws to a much greater extent on globalization and immigration.

In the United States today, immigrant women from a few non-European nations are established as paid domestic workers. These women—who hail primarily from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean and who are perceived as “nonwhite” in Anglo-American contexts—hold various legal statuses. Some are legal permanent residents or naturalized U.S. citizens, many as beneficiaries of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act's amnesty-legalization program.21 Central American women, most of whom entered the United States after the 1982 cutoff date for amnesty, did not qualify for legalization, so in the 1990s they generally either remained undocumented or held a series of temporary work permits, granted to delay their return to war-ravaged countries.22 Domestic workers who are working without papers clearly face extra burdens and risks: criminalization of employment, denial of social entitlements, and status as outlaws anywhere in the nation. If they complain about their jobs, they may be threatened with deportation.23 Undocumented immigrant workers, however, are not the only vulnerable ones. In the 1990s, even legal permanent residents and naturalized citizens saw their rights and privileges diminish, as campaigns against illegal immigration metastasized into more generalized xenophobic attacks on all immigrants, including those here with legal authorization. Immigration status has clearly become an important axis of inequality, one interwoven with relations of race, class, and gender, and it facilitates the exploitation of immigrant domestic workers.

Yet race and immigration are interacting in an important new way, which Latina immigrant domestic workers exemplify: their position as “foreigners” and “immigrants” allows employers, and the society at large, to perceive them as outsiders and thereby overlook the contemporary racialization of the occupation. Immigration does not trump race but, combined with the dominant ideology of a “colorblind” society, manages to shroud it.24

With few exceptions, domestic work has always been reserved for poor women, for immigrant women, and for women of color; but over the last century paid domestic workers have become more homogenous, reflecting the subordinations of both race and nationality/immigration status. In the late nineteenth century, this occupation was the most likely source of employment for U.S.-born women. In 1870, according to the historian David M. Katzman, two-thirds of all nonagricultural female wage earners worked as domestics in private homes. The proportion steadily declined to a little over one-third by 1900, and to one-fifth by 1930. Alternative employment opportunities for women expanded in the mid- and late twentieth century, so by 1990, fewer than 1 percent of employed American women were engaged in domestic work.25 Census figures, of course, are notoriously unreliable in documenting this increasingly undocumentable, “under-the-table” occupation, but the trend is clear: paid domestic work has gone from being either an immigrant woman's job or a minority woman's job to one that is now filled by women who, as Latina and Caribbean immigrants, embody subordinate status both racially and as immigrants.26

Regional racializations of the occupation were already deeply marked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the occupation recruited women from subordinate racial-ethnic groups. In northeastern and midwestern cities of the late nineteenth century, single young Irish, German, and Scandinavian immigrants and women who had migrated from the country to the city typically worked as live-in “domestic help,” often leaving the occupation when they married.27 During this period, the Irish were the main target of xenophobic vilification. With the onset of World War I, European immigration declined and job opportunities in manufacturing opened up for whites, and black migration from the South enabled white employers to recruit black women for domestic jobs in the Northeast. Black women had always predominated as a servant caste in the South, whether in slavery or after, and by 1920 they constituted the single largest group in paid domestic work in both the South and the Northeast.28 Unlike European immigrant women, black women experienced neither individual nor intergenerational mobility out of the occupation, but they succeeded in transforming the occupation from one characterized by live-in arrangements, with no separation between work and social life, to live-out “day work”—a transformation aided by urbanization, new interurban transportation systems, and smaller urban residences.29

In the Southwest and the West of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the occupation was filled with Mexican American and Mexican immigrant women, as well as Asian, African American, and Native American women and, briefly, Asian men. Asian immigrant men were among the first recruits for domestic work in the West.30 California exceptionalism—its Anglo-American conquest from Mexico in 1848, its ensuing rapid development and overnight influx of Anglo settlers and miners, and its scarcity of women—initially created many domestic jobs in the northern part of the territory for Chinese “houseboys,” laundrymen, and cooks, and later for Japanese men, followed by Japanese immigrant women and their U.S.-born daughters, the nisei, who remained in domestic work until World War II.31 Asian American women's experiences, as Berkeley sociologist Evelyn Nakano Glenn has demonstrated, provide an intermediate case of intergenerational mobility out of domestic work between that of black and Chicana women who found themselves, generation after generation, stuck in the occupational ghetto of domestic work and that of European immigrant women of the early twentieth century who quickly moved up the mobility ladder.32

For Mexican American women and their daughters, domestic work became a dead-end job. From the 1880s until World War II, it provided the largest source of nonagricultural employment for Mexican and Chicana women throughout the Southwest. During this period, domestic vocational training schools, teaching manuals, and Americanization efforts deliberately channeled them into domestic jobs.33 Continuing well into the 1970s throughout the Southwest, and up to the present in particular regions, U.S.-born Mexican American women have worked as domestics. Over that time, the job has changed. Much as black women helped transform the domestic occupation from live-in to live-out work in the early twentieth century, Chicanas in the Southwest increasingly preferred contractual house-cleaning work—what Romero has called “job work”—to live-in or daily live-out domestic work.34

While black women dominated the occupation throughout the nation during the 1950s and 1960s, there is strong evidence that many left it during the late 1960s. The 1970 census marked the first time that domestic work did not account for the largest segment of employed black women; and the proportion of black women in domestic work continued to drop dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s, falling from 16.4 percent in 1972 to 7.4 percent in 1980, then to 3.5 percent by the end of the 1980s.35 By opening up public-sector jobs to black women, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it possible for them to leave private domestic service. Consequently, both African American and Mexican American women moved into jobs from which they had been previously barred, as secretaries, sales clerks, and public-sector employees, and into the expanding number of relatively low-paid service jobs in convalescent homes, hospitals, cafeterias, and hotels.36

These occupational adjustments and opportunities did not go unnoticed. In a 1973 Los Angeles Times article, a manager with thirty years of experience in domestic employment agencies reported, “Our Mexican girls are nice, but the blacks are hostile.” Speaking very candidly about her contrasting perceptions of Latina immigrant and African American women domestic workers, she said of black women, “you can feel their anger. They would rather work at Grant's for $1.65 an hour than do housework. To them it denotes a lowering of self.”37 By the 1970s black women in the occupation were growing older, and their daughters were refusing to take jobs imbued with servitude and racial subordination. Domestic work, with its historical legacy in slavery, was roundly rejected. Not only expanding job opportunities but also the black power movement, with its emphasis on self-determination and pride, dissuaded younger generations of African American women from entering domestic work.

It was at this moment that newspaper reports, census data, and anecdotal accounts first register the occupation's demographic shift toward Latina immigrants, a change especially pronounced in areas with high levels of Latino immigration. In Los Angeles, for example, the percentage of African American women working as domestics in private households fell from 35 percent to 4 percent from 1970 to 1990, while foreign-born Latinas increased their representation from 9 percent to 68 percent.38 Again, since census counts routinely underestimate the poor and those who speak limited or no English, the women in this group may represent an even larger proportion of private domestic workers.

Ethnographic case studies conducted not only in Los Angeles but also in Washington, D.C., San Francisco, San Diego, Houston, El Paso, suburban areas of Long Island, and New York City provide many details about the experiences of Mexican, Caribbean, and Central American women who now predominate in these metropolitan centers as nanny/housekeepers and housecleaners.39 Like the black women who migrated from the rural South to northern cities in the early twentieth century, Latina immigrant women newly arrived in U.S. cities and suburbs in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s often started as live-ins, sometimes first performing unpaid household work for kin before taking on very low paying live-in jobs for other families.40 Live-in jobs, shunned by better-established immigrant women, appeal to new arrivals who want to minimize their living costs and begin sending their earnings home. Vibrant social networks channel Latina immigrants into these jobs, where the long hours and the social isolation can be overwhelming. As time passes, many of the women seek live-out domestic jobs. Despite the decline in live-in employment arrangements at the century's midpoint, the twentieth century ended in the United States much as it began, with a resurgence of live-in jobs filled by women of color—now Latina immigrants.

Two factors of the late twentieth century were especially important in creating this scenario. First, as many observers have noted, globalization has promoted higher rates of immigration. The expansion of U.S. private investment and trade; the opening of U.S. multinational assembly plants (employing mostly women) along the U.S.-Mexico border and in Caribbean and Central American nations, facilitated by government legislative efforts such as the Border Industrialization Program, the North American Free Trade Agreement, and the Caribbean Basin Initiative; the spreading influence of U.S. mass media; and U.S. military aid in Central America have all helped rearrange local economies and stimulate U.S.-bound migration from the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America. Women from these countries have entered the United States at a propitious time for families looking to employ housecleaners and nannies.41

Second, increased immigration led to the racialized xenophobia of the 1990s. The rhetoric of these campaigns shifted focus, from attacking immigrants for lowering wages and competing for jobs to seeking to bar immigrants' access to social entitlements and welfare. In the 1990s, legislation codified this racialized nativism, in large part taking aim at women and children.42 In 1994 California's Proposition 187, targeting Latina immigrants and their children, won at the polls; and although its denial of all public education and of publicly funded health care was ruled unconstitutional by the courts, the vote helped usher in new federal legislation. In 1996 federal welfare reform, particularly the Immigration Reform Act and Individual Responsibility Act (IRAIRA), codified the legal and social disenfranchisement of legal permanent residents and undocumented immigrants. At the same time, language—and in particular the Spanish language—was becoming racialized; virulent “English Only” and anti-bilingual education campaigns and ballot initiatives spread.

Because Latina immigrants are disenfranchised as immigrants and foreigners, Americans can overlook the current racialization of the job. On the one hand, racial hostilities and fears may be lessened as increasing numbers of Latina and Caribbean nannies care for tow-headed children. As Sau-ling C. Wong suggests in an analysis of recent films, “in a society undergoing radical demographic and economic changes, the figure of the person of color patiently mothering white folks serves to allay racial anxieties.”43 Stereotypical images of Latinas as innately warm, loving, and caring certainly round out this picture. Yet on the other hand, the status of these Latinas as immigrants today serves to legitimize their social, economic, and political subordination and their disproportionate concentration in paid domestic work.

Such legitimation makes it possible to ignore American racism and discrimination. Thus the abuses that Latina domestic workers suffer in domestic jobs can be explained away because the women themselves are foreign and unassimilable. If they fail to realize the American Dream, according to this distorted narrative, it is because they are lazy and unmotivated or simply because they are “illegal” and do not merit equal opportunities with U.S.-born American citizens. Contemporary paid domestic work in the United States remains a job performed by women of color, by black and brown women from the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico. This racialization of domestic work is masked by the ideology of “a colorblind society” and by the focus on immigrant “foreignness.”

GLOBAL TRENDS IN PAID DOMESTIC WORK

Just as paid domestic work has expanded in the United States, so too it appears to have grown in many other postindustrial societies—in Canada and in parts of Europe—in the “newly industrialized countries” (NICs) of Asia, and in the oil-rich nations of the Middle East. Around the globe Caribbean, Mexican, Central American, Peruvian, Sri Lankan, Indonesian, Eastern European, and Filipina women—the latter in disproportionately great numbers—predominate in these jobs. Worldwide, paid domestic work continues its long legacy as a racialized and gendered occupation, but today divisions of nation and citizenship are increasingly salient. Rhacel Parreñas, who has studied Filipina domestic workers, refers to this development as the “international division of reproductive labor,” and Anthony Richmond has called it part of a broad, new “global apartheid.”44

In the preceding section, I highlighted the inequalities of race and immigration in the United States, but we must remember that the inequality of nations is a key factor in the globalization of contemporary paid domestic work. This inequality has had three results. First, around the globe, paid domestic work is increasingly performed by women who leave their own nations, their communities, and often their families of origin to do it. Second, the occupation draws not only women from the poor socioeconomic classes but also women of relatively high status in their own countries—countries that colonialism made much poorer than those countries where they go to do domestic work. Thus it is not unusual to find middle-class, college-educated women working in other nations as private domestic workers. Third, the development of service-based economies in postindustrial nations favors the international migration of women laborers. Unlike in earlier industrial eras, today the demand for gendered labor favors migrant women's services.

Nations use vastly different methods to “import” domestic workers from other countries. Some countries have developed highly regulated, government-operated, contract labor programs that have institutionalized both the recruitment and working conditions of migrant domestic workers. Canada and Hong Kong exemplify this approach. Since 1981 the Canadian federal government has formally recruited thousands of women to work as live-in nanny/housekeepers for Canadian families. Most come from third world countries, the majority in the 1980s from the Caribbean and in the 1990s from the Philippines; and once in Canada, they must remain in live-in domestic service for two years, until they obtain their landed immigrant status, the equivalent of the U.S. “green card.”45 During this period, they must work in conditions reminiscent of formal indentured servitude and they may not quit their jobs or collectively organize to improve job conditions.

Similarly, since 1973 Hong Kong has relied on the formal recruitment of domestic workers, mostly Filipinas, to work on a full-time, live-in basis for Chinese families. Of the 150,000 foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong in 1995,130,000 hailed from the Philippines, with smaller numbers drawn from Thailand, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, and Nepal.46 Just as it is now rare to find African American women employed in private domestic work in Los Angeles, so too have Chinese women vanished from the occupation in Hong Kong. As Nicole Constable reveals in her detailed study, Filipina domestic workers in Hong Kong are controlled and disciplined by official employment agencies, employers, and strict government policies.47 Filipinas and other foreign domestic workers recruited to Hong Kong find themselves working primarily in live-in jobs and under two-year contracts that stipulate job rules, regulations for bodily display and discipline (no lipstick, nail polish, or long hair; submission to pregnancy tests; etc.), task timetables, and the policing of personal privacy.

In the larger global context, the United States remains distinctive, as it follows a more laissez-faire approach to incorporating immigrant women into paid domestic work.48 Unlike in Hong Kong and Canada, here there is no formal government system or policy to legally contract with foreign domestic workers. In the past, private employers in the United States were able to “sponsor” individual immigrant women working as domestics for their green cards, sometimes personally recruiting them while they were vacationing or working in foreign countries, but this route is unusual in Los Angeles today.49 For such labor certification, the sponsor must document that there is a shortage of labor able to perform a particular, specialized job—and in Los Angeles and many other parts of the country, demonstrating a shortage of domestic workers has become increasingly difficult. And it is apparently unnecessary, as the significant demand for domestic workers in the United States is largely filled not through formal channels but through informal recruitment from the growing number of Caribbean and Latina immigrant women who are already living (legally or illegally) in the United States. The Immigration and Naturalization Service, the federal agency charged with stopping illegal migration, has historically served the interest of domestic employers and winked at the hiring of undocumented immigrant women in private homes.

As we compare the hyperregulated employment systems in Hong Kong and Canada with the U.S. approach to domestic work, we must distinguish between the regulation of labor and the regulation of foreign domestic workers. As Sedef Arat-Koc puts it in discussing the labor conditions of Filipina and Caribbean domestic workers in Canada, “while their conditions of work have been under-regulated, domestic workers themselves, especially those from the ‘least desirable’ backgrounds, have become over-regulated.”50 Here, the United States is again an exception. U.S. labor regulations do cover private domestic work—but no one knows about them. As I describe in detail in chapter 8, domestic workers' wages and hours are governed by state and federal law, and special regulations cover such details as limits on permissible deductions for breakage and for boarding costs of live-in workers. These regulations did not fall from the sky: they are the result of several important, historic campaigns organized by and for paid domestic workers. Most U.S. employers now know, after the Zoë Baird incident, about their obligations for employment taxes—though these obligations are still widely ignored—but few employers and perhaps fewer employees know about the labor laws pertaining to private domestic work. It's almost as though these regulations did not exist. At the same time, the United States does not maintain separate immigration policies for domestic workers, of the sort that mandate live-in employment or decree instant deportation if workers quit their jobs.

This duality has two consequences. On the one hand, both the absence of hyperregulation of domestic workers and the ignorance about existing labor laws further reinforce the belief that paid domestic work is not a real job. Domestic work remains an arrangement that is thought of as private: it remains informal, “in the shadows,” and outside the purview of the state and other regulating agencies. On the other hand, the absence of state monitoring of domestic job contracts and of domestic workers' personal movement, privacy, and bodily adornment suggests an opening to upgrade domestic jobs in the United States. Unlike in Hong Kong and Canada, for example, where state regulations prevent Filipina domestic workers from quitting jobs that they find unsatisfactory or abusive, in Los Angeles, Latina immigrant domestic workers can—and, as we'll see in chapter 5, do—quit their jobs. Certainly they face limited options when they seek jobs outside of private homes, but it is important to note that they are not yoked by law to the same boss and the same job.

The absence of a neocolonialism state-operated, contractual system for domestic work thus represents an opportunity to seek better job conditions. The chance of success might be improved if existing labor regulations were strengthened, if domestic workers were to work at collective organizing, and if informational and educational outreach to the domestic workers were undertaken. But to be effective, these efforts must occur in tandem with a new recognition that the relationships in paid domestic work are relations of employment.

SOCIAL REPRODUCTION AND NEW

REGIMES OF INEQUALITY:

TRANSNATIONAL MOTHERHOOD

Sometimes it is necessary to state the obvious. In employer households, women are almost exclusively in charge of seeking and hiring domestic workers. This social fact speaks to the extent to which feminist, egalitarian goals of sharing household cleaning and care work remain unachieved. Even among wealthy white women born and raised in the United States in the late twentieth century, few escape the fetters of unpaid social reproductive labor. As many observers have noted, their reliance on housecleaners and nannies allows well-to-do women to act, in effect, as contractors.51 By subcontracting to private domestic workers, these women purchase release from their gender subordination in the home, effectively transferring their domestic responsibilities to other women who are distinct and subordinate by race and class, and now also made subordinate through language, nationality, and citizenship status. The work performed by Latina, Caribbean, and Filipina immigrant women today subsidizes the work of more privileged women, freeing the latter to join the productive labor force by taking jobs in business and the professions, or perhaps enabling wealthier women to become more active consumers and volunteers and to spend more time culturally grooming their children and orchestrating family recreation. Consequently, male privilege within homes and families remains uncontested and intact, and new inequalities are formed.

Some feminist theorists, especially those influenced by Marxist thought, have used the term “social reproduction” or “reproductive labor” to refer to the myriad of activities, tasks, and resources expended in the daily upkeep of homes and people. Taking care of ourselves, raising the next generation, and caring for the sick and elderly are projects requiring constant vigilance and dedication. As the sociologists Barbara Laslett and Joanna Brenner put it, “renewing life is a form of work, a kind of production, as fundamental to the perpetuation of society as the production of things.”52 More recently, feminist scholars influenced by feminist Scandinavian research on social welfare have shifted their focus to “caring” and “care work.” Regardless of specific theoretical underpinnings, two important points must be emphasized.

First, the way we socially organize reproductive labor has varied historically, and across culture and class. Different arrangements bring about different social consequences and different forms of inequality. Second, our definitions of what are appropriate forms and goals of social reproduction also vary. What passes today as a clean house or proper meal? What behavioral or educational expectations do we hold for our children? The proliferation of fast, frozen, and already prepared foods, and of women's magazines that promise to reveal how to make family meals in ten minutes, suggests that standards for what constitutes a proper American middle-class meal have dropped. (Meal preparation is a task rarely assigned to contemporary domestic workers; perhaps convenience foods have made it trivial, or perhaps meal preparation remains too symbolic of family life to assign to an outsider.)53 Simultaneously, standards of hygiene and home cleanliness, like the size of the average American home, have increased throughout the twentieth century And perhaps nowhere has the bar been raised more than regarding what constitutes proper child rearing, especially among middle-class professionals. Parents (mostly mothers) study books and attend classes on how to provide babies and toddlers with appropriate developmental stimulation, and middle-class children today are generally expected to perform grueling amounts of homework, participate in a variety of organized sports and social clubs, take music lessons, and exhibit prescribed stages of emotional literacy and sensitivity. In any society, raising children is work that requires tremendous expenditures of manual, mental, spiritual, and emotional energy, but enormous amounts of money and work are now invested in developing middle-class and upper-class children, presumably so that they can assume or better their parents' social status.54 Paid domestic work, especially the work of nanny/housekeepers, occurs in this context of diminished expectations for preparing meals and heightened standards for keeping homes clean and rearing children.

Inequalities of race, class, and gender have long characterized private, paid domestic work, and as we have seen, globalization is creating new regimes of inequality. We must remember that the immigrant women who are performing other people's private reproductive work are women who were themselves socially reproduced in other societies. The costs of their own social reproduction—everything that it took to raise them from infants to working adults—were shouldered by families, governments, and communities in Mexico and in Central American and Caribbean nations. For this reason, their employment as domestic workers represents a bargain for American families and American society The inequalities of social reproduction in these Latinas' contemporary family and work lives, however, are even more glaringly apparent when we consider their own children.

Today, many of these domestic workers care for the homes and children of American families while their children remain “back home” in their societies of origin. This latter arrangement, which I call transnational motherhood, signals new international inequalities of social reproduction.55 A continuing strain of contemporary xenophobia in California protests the publicly funded schooling for the children of Mexican undocumented immigrants (e.g., Proposition 187 in 1994 and the 1999 attempt by the Anaheim School Board to “bill” the Mexican federal government for the schooling of Mexican children in Orange County), but this same logic might be used to promote an alternative view, one emphasizing that the human investment and reaping of benefits occurs in precisely the opposite direction. Though the children (themselves U.S. citizens) of undocumented immigrants are later likely, as adults, to work and reside in the same society in which they were raised (the United States), Central American and Mexican immigrant women enter U.S. domestic jobs as adults, already having been raised, reared, and educated in another society. Women raised in another nation are using their own adult capacities to fulfill the reproductive work of more privileged American women, subsidizing the careers and social opportunities of their employers. Yet the really stinging injury is this: they themselves are denied sufficient resources to live with and raise their own children.

Since the early 1980s, thousands of Central American women and Mexican women in increasing numbers have left their children behind with grandmothers, with other female kin, with the children's fathers, and sometimes with paid caregivers while they themselves migrate to work in the United States. The subsequent separations of time and distance are substantial; ten or fifteen years may elapse before the women are reunited with their children. Feminist scholarship has shown us that isolationist, privatized mothering, glorified and exalted though it has been, is just one historically and culturally specific variant among many; but this model of motherhood continues to inform many women's family ideals.56 In order to earn wages by providing child care and cleaning for others, many Latina immigrant women must transgress deeply ingrained and gender-specific spatial and temporal boundaries of work and family.

One precursor to these arrangements is the mid-twentieth-century Bracero Program, discussed above. This long-standing arrangement of Mexican “absentee fathers” coming to work in the United States as contracted agricultural laborers is still in force today, though the program has ended. When these men come north and leave their families in Mexico, they are fulfilling masculine obligations defined as breadwinning for the family. When women do so, they are entering not only another country but also a radical, gender-transformative odyssey. As their separations of space and time from their communities of origin, homes, children, and sometimes husbands begin, they must cope with stigma, guilt, and others' criticism.

The ambivalent feelings and new ideological stances accompanying these new arrangements are still in flux, but tensions are evident. As they wrestle with the contradictions of their lives and beliefs, and as they leave behind their own children to care for the children of strangers in a foreign land, these Latina domestic workers devise new rhetorical and emotional strategies. Some nanny/housekeepers develop very strong ties of affection with the children in their care during their long workweeks, and even more grow critical of their employers. Not all nanny/housekeepers bond tightly with their employers' children (and they do so selectively among the children), but most of them sharply criticize what they perceive as their employers' neglectful parenting—typically, they blame the biological mothers. They indulge in the rhetoric of comparative mothering, highlighting the sacrifices that they themselves make as poor, legally disenfranchised, racially subordinate working mothers and setting them in contrast to the substandard mothering provided by their multiply privileged employers.

Notions of childhood and motherhood are intimately bound together, and when the contrasting worlds of domestic employers and employees overlap, different meanings and gauges of motherhood emerge. In some ways, the Latina transnational mothers who work as nanny/housekeepers sentimentalize their employers' children more than their own. This strategy enables them to critique their employers, especially the homemakers who neither leave the house to work nor care for their children every day. The Latina nannies can endorse motherhood as a full-time vocation for those able to afford it, while for those suffering financial hardships they advocate more elastic definitions of motherhood—including forms of transnational motherhood that may force long separations of space and time on a mother and her children. Under these circumstances, and when they have left suitable adults in charge, they tell themselves that “the kids are all right.”

These arrangements provoke new debates among the women. Because there is no universal or even widely shared agreement about what constitutes “good mothering,” transnational mothers must work hard to defend their choices. Some Latina nannies who have their children with them in the United States condemn transnational mothers as “bad women.” In response, transnational mothers construct new measures to gauge the quality of mothering. By setting themselves against the negative models of mothering that they see in others—especially the models that they can closely scrutinize in their employers' homes—transnational mothers redefine the standards of good mothering. At the same time, selectively developing motherlike ties with other people's children allows them to enjoy the affectionate, face-to-face interactions that they cannot experience on a daily basis with their own children.

Social reproduction is not simply the secondary outcome of markets or modes of production. In our global economy, its organization among privileged families in rich nations has tremendous repercussions for families, economies, and societies around the world. The emergence of transnational motherhood underscores this point, and shows as well how new inequalities and new meanings of family life are formed through contemporary global arrangements in paid domestic work.

POINT OF DEPARTURE

As we have seen, no single cause explains the recent expansion of paid domestic work. Several factors are at work, including growing income inequality; women's participation in the labor force, especially in professional and managerial jobs; the relatively underdeveloped nature of day care in the United States—as well as middle-class prejudices against using day care; and the mass immigration of women from Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico. We have also examined the cultural and social perceptions that prevent paid domestic work from being seen and treated as employment, and have observed how contemporary racialization and immigration affect the job. Yet simply understanding the conditions that have fostered the occupation's growth, the widely held perceptions of the job, or even the important history of the occupation's racialization tells us little about what is actually happening in these jobs today. How are they organized, and how do employers and employees experience them? The remainder of this book draws on interviews, a survey, and limited ethnographic observations made in Los Angeles to answer these questions.

Jobs in offices, in factories, or at McDonald's are covered by multiple regulations provided by government legislation, by corporate, managerial strategies, by employee handbooks, and sometimes by labor unions; but paid domestic work lacks any such formal, institutionalized guides. It is done in the private sphere and its jobs are usually negotiated, as Judith Rollins puts it, “between women.” More broadly, I argue, paid domestic work is governed by the parallel and interacting networks of women of different classes, ethnicities, and citizenship statuses who meet at multiple work sites in isolated pairs. While employer and employee individually negotiate the job, their tactics are informed by their respective social networks. Today, many employers in Los Angeles and many Latina immigrants are, generationally speaking, new to the occupation. Rather than relying on information passed down from their mothers, both employers and employees draw on information exchanged within their own respective networks of friends, kin, and acquaintances and, increasingly, on lessons learned from their own experiences to establish the terms of private, paid domestic work (hiring practices, pay scales, hours, job tasks, etc.). That employers rarely identify themselves as employers, just as many employees hesitate to embrace their social status as domestic workers, means that the job is not always regarded as a job, leading to problematic relations and terms of employment.

Although there are regularities and patterns to the job, contemporary paid domestic work is not monolithic. I distinguish three common types of jobs:57 (1) Live-in nanny/housekeeper. The live-in employee works for and lives with one family, and her responsibilities generally include caring for the children and the household. (2) Live-out nanny/housekeeper. The employee works five or six days a week for one family, tending to the children and the household, but returns to her apartment, her own community and sometimes her own family at night. (3) Housecleaner. The employee cleans houses, working for several different employers on a contractual basis, and usually does not take care of children as part of her job. Housecleaners, as Mary Romero's research emphasizes, work shorter hours and receive higher pay than do other domestic workers, enjoying far greater job flexibility and autonomy; and because they have multiple jobs, they retain more negotiating power with their employers.58 The following chapter profiles some of the women who do these jobs in Los Angeles.