Читать книгу Domestica - Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface to the First Edition

Can we conceive of a Los Angeles where there is, as the title of a short film puts it, “A Day without a Mexican”?1 In fact, as I learned while chatting with domestic workers at parks and bus stops, this is an exercise regularly indulged in by Mexican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan women who work in middle-class and upper-middle-class homes throughout Los Angeles. “If we called a three-day strike,” nannies say to their peers, “How many days would it take before we shut it all down?” Not only would households fall into a state of chaos, but professionals, managers, and office workers of all sorts would find themselves unable to perform their own jobs. Latina domestic workers debate this scenario with humor—some arguing that it might take two days, others chiming in with four. They know that in their job, a general strike is unlikely. Yet their strident humor is bolstered by the resurgence of militant unionism among Latino immigrant janitors and hotel and restaurant employees and by collective organizing among gardeners, day laborers, and drywallers in California. Significantly, their running dialogue speaks to a shared recognition of their own indispensability. In their own conversations, they reclaim what their job experiences often deny them: social recognition and dignity.

Latina immigrant labor, and specifically the work of housecleaners and nanny/housekeepers, constitutes a bedrock of our contemporary U.S. culture and economy, yet the work and the women who do it remain invisible and disregarded. Paid domestic work enjoyed a short-lived flurry of media attention in the early 1990s, when the transgressions of Zoë Baird and Kimba Wood (and several other political nominees and elected officials) came to light, but the public gaze was fleeting.2 Moreover, attention focused neither on the quality of the jobs nor on the women who do the work but on their employers, who had failed to pay employment taxes.

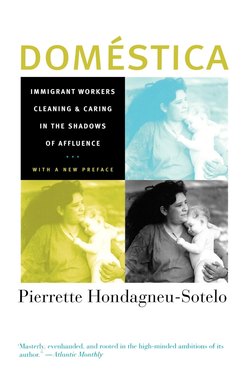

Private paid domestic work, in which one individual cleans and cares for another individual or family, poses an enormous paradox. In the United States today, these jobs remain effectively unregulated by formal rules and contracts. Consequently, even today they often resemble relations of servitude that prevailed in earlier, precapitalist feudal societies. These contemporary work arrangements contradict American democratic ideals and modern contractual notions of employment. Doméstica reveals how these fundamental tensions in American social life are played out in private homes, between the women who do the work and those who employ them.

Paid domestic work is widely recognized as part of the informal “shadow” or “under the table” economy. Although wage and hour regulations do cover the job, scarcely anyone, employee or employer, knows about them. Government regulations remain ineffective, and there are no employee handbooks, unions, or management guidelines to help set wages or job duties or to stipulate how the work should be performed. The jobs are done in isolated, private, widely dispersed households, and typically involve negotiations between two individuals—usually women from radically different backgrounds. Yet despite this laissez-faire context, there are striking regularities in wages, hours, benefits, tasks, and directions; in disputes that arise; and in modes of recruitment, hiring, and firing. In this book, I identify many of these patterns. Relying on primary information gathered in the mid- to late 1990s from more than two hundred people in Los Angeles (in-depth interviews with 68 individuals, a survey of 153 Latina domestic workers, and ethnographic observations in various settings), I examine how the practices and concerns of both employers and employees shape how paid domestic work occurs today.

There are many lived dramas in America today, and among the least visible and most deeply felt are those that unfold behind carefully manicured lawns and residential facades. My book highlights the voices, experiences, and views both of the Mexican and Central American women who care for other people's children and homes and of the women in Los Angeles who employ them. The study of paid domestic work thus offers a key window through which we can view contemporary relations between women whose social positions are in stark contrast: between poor women and affluent families; between foreign-born, immigrant women and U.S.-born citizens; and between members of the growing, but still economically and racially subordinate, Latino communities and the shrinking population of white suburban residents, many of whom feel increasingly anxious about these demographic developments. Differences of class, race, nationality, and citizenship characterize the study's participants, yet this is an occupation in which the chasm of social differences plays out in physical proximity. Unlike the working poor who toil in factories and fields, domestic workers see, touch, and breath the material and emotional world of their employers' homes. They scrub grout, coax reluctant children to nap and eat their vegetables, launder and fold clothes, mop, dust, vacuum, and witness intimate and otherwise private family dynamics. Inside the palatial mansion, the sprawling ranch-style home, or the modest duplex, they do these activities over and over again.

Ambivalence characterizes the governance of private paid domestic work in the United States. Many contemporary employers of domestic workers feel awkward or ambivalent about the ambiguous arrangements that they make. In part, this ambivalence reflects American unease with the whole image of domestic service. Contemporary inequalities notwithstanding, Americans have no titled aristocracy and no feudal past, and the omnipresent ideology of freedom, equality, and democracy clashes with what many American employers of domestic workers experience in their lives. Some employers try different strategies to address their sense of disquiet. Indeed, most of them think of themselves not as “employers” but rather as “consumers.” Some of them try to not witness the work as it is performed, deliberately leaving the house when their house-cleaners are there even if they have no need to be elsewhere. In casual conversations, they may refer to the Guatemalan woman who works in their home as their “baby-sitter,” invoking the image of a high school girl who lives down the street and looks after the kids on Saturday night. Nanny, after all, sounds too unrepentantly British, and too class marked—though some do flaunt their privilege, grateful at least to be on the employers' side of the fence. Maid, a term that sounds servile, anachronistic, and almost premodern, is rarely used by anyone. Some employers try to snip off the price tags on new clothing and home furnishings before the Latina domestic workers read them because they fear the women will compare the prices of those items with their wages—which they invariably do. While employers often feel guilty about “having so much” around someone who “has so little,” the women who do the work resent not their affluence but the job arrangements, which generally afford the workers little in the way of respect and living wages.

Domestic work was the single largest category of paid employment for all women in the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in large part because other opportunities were not available. Although the timing of exit varies by race and region, by the mid-twentieth century the doors to retail, clerical, and professional jobs were opening for many working women, and single and married women walked out of their homes and into formal-sector employment.3 Paid domestic work declined, a trend leading some commentators to predict the occupation's demise. But instead in the late twentieth century new domestic demands arose and new recruits were found, now crossing the southern border to reach the doorstep of domestic work. The work of cleaning houses and caring for children gradually left the hands of wives and mothers and entered the global marketplace. In the process, it has become the domain of disenfranchised immigrant women of color.

I focus not on the sensationalistic abuses and crimes in domestic work (e.g., the nanny who beats the children, or the employer who holds the housekeeper hostage), but rather on the everyday organization of an occupation and the concerns of the women who do the work. The “L.A. stories” presented here underline that social relationships—among the employees, among the employers, and between the two groups—organize the job. These social relationships, as well-intentioned as some of them may be, sometimes lead to less than desirable job performance and conditions of work. Problems and abuses arise that harm both employers and employees, but especially the latter, primarily because paid domestic work is not treated as employment. Remedying the problems and social injustices of paid domestic work, I argue, will involve bestowing social recognition on the work of caring for homes and for children, and learning to see and treat paid domestic work as employment.

SOCIAL LOCATIONS, RESEARCH LOCATIONS

I wrote this book on time stolen away from teaching and administrative duties at my university, and away from my own housecleaning, grocery shopping, cooking, and child care. Even when blessed with a sabbatical and summer vacations, I struggled to find time when school holidays, or unexpected bouts of chicken pox or flu, would not derail my research and writing momentum. And although I pay a Salvadoran woman to clean my house every other week, I still feel there are not enough hours in the day to do everything I need to do. In this regard, I'm afraid I fit the profile of the harried working mom.

Here's the ironic rub: in this book, I argue that cleaning houses and taking care of children is “real work,” yet in the ways I live my life, I still define my real work as my teaching, research, and writing, not the varied activities involved in taking care of my children and home. I love my family and my home, and I spend a good part of each day thinking about, planning, and engaging in family and home activities. Still, if someone asks me, “What do you do?” I tell them what I do for a living. My job as a university professor is privileged work that has been a struggle for me to achieve; I like it, and I don't for a moment take it for granted. The same can truthfully be said of my domestic life, but why don't I claim my own homemaking and care work in the same way? There are many reasons to explain this, and they are primarily social, not individual. They have to do with how we regard—or, more accurately, disregard—the work of running families and households, how we romanticize family as a “natural” arena of expression for women, and how we conceptualize and reward “work,” which remains, even as we enter the twenty-first century, something we still think about in terms of nineteenth-century models of production.

Several other biographical features about me frame this study. I am the daughter of a Latina woman who, like many modestly educated women in mid-twentieth-century Latin America, migrated from the countryside to the city to work as a live-in nanny/housekeeper. Eventually, employment in her native Chile for the American family of an Anaconda copper mining engineer was her ticket to California, bought with indentured labor. When the family that brought her to the United States refused to pay her, she found live-in domestic jobs with other well-to-do American families before eventually marrying my father, a French gardener whom she met on the job. I grew up hearing all kinds of stories about “la señora Elsa” and “la Mrs. Lowe” (the article always prefacing the name, thereby signaling a formidable presence). Throughout my childhood and adolescence, my family maintained close ties with a Chilean family for whom my mother had once worked, well after she had left their employ and migrated to the United States.4

Today, my husband and I do laundry, cook, and clean daily, but we also pay a Salvadoran woman to clean our house. Every other Thursday she drives from her apartment near downtown Los Angeles to our suburban home to sweep and mop the hardwood floors, vacuum the carpets, dust the furniture, and scrub, wipe, and polish the bathrooms and kitchen to a blinding gleam. I love the way the house looks after she's done her job; but like many of the employers that I interviewed for this study, I remain deeply ambivalent about the glaring inequalities exposed by this arrangement—and exposed in a particularly visible and visceral way. Capitalist manufacturing misery abounds in this world; but when I purchase Nike shoes or Gap jeans, my reliance on child labor in Mauritania or Pakistan, or on Latina garment workers who toil in sweatshops just a stone's throw away from my office at USC, remains conveniently hidden and invisible in the object of consumption. I take possession of a new item, and no one but the cashier stares back at me. By contrast, my privileges and complicity in a worldwide system of inequalities and exploitation are thrown into relief by the face-to-face relations between me and the woman who cleans my house.

When colleagues and students in my classes have discussed these issues, some of them have argued passionately and compellingly that we cannot have a just society until everyone cleans up and picks up after themselves, regardless of their race, sex, or immigration or class status. They might be right (and I'm certainly in favor of men and boys learning to do their fair share), but I think an abolitionist program smacks of the Utopian, not the feasible. Domestic work should not fall disproportionately on the shoulders of any one group (such as Filipina, or Latina, or Caribbean immigrant women); but putting an end to domestic employment is not the answer. Upgrading the occupation, a change ushered in by systemic regulation and by public recognition that this seemingly private activity is a job—one that creates particular obligations in both employees and employers—is our best chance for salvaging paid domestic work, for increasing the opportunities of those who do the work and of their families, and for reclaiming the dignity and humanity of both employees and employers.

Since 1990, well before I began the research for this book, I have worked toward that end with a group of women under the auspices of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA). The project began as an information and outreach program organized by immigrant rights attorneys, community organizers, and myself, but today it is a full-fledged, dues-collecting membership organization called the Domestic Workers' Association (DWA), which is part of CHIRLA. Similar organizations have sprouted up in other cities around the country, and they have long been common in Latin America. I discuss the DWA in Chapter 8; here it is mentioned only to contextualize my relationship to this topic. All research is partial, situated and shaped by who we are. My multiple social locations—as the daughter of a former domestic worker, as a current employer, and as an advocate—have certainly shaped my approach and my emphases. My engagement with previous research and scholarship, particularly that focusing on gender, immigration, and paid domestic work, also situates this study.

RESEARCH DESCRIPTION

I began this project as an interview study, but state and national politics swirling around private domestic work and immigration sometimes made it difficult to find interview participants. From the beginning, I knew I couldn't understand this occupation without understanding those who hire nanny/housekeepers and housecleaners, but some employers turned down my request to come to their home and tape-record them, fearing that I might be an 1RS agent posing as a sociologist (the Zoë Baird and Kimba Wood incidents were fresh in their memories). Others said they were too busy. Meanwhile, some Latina immigrant women, in the climate of fear created by California's Proposition 187 (which sought to bar undocumented immigrants and their children from receiving publicly funded health care and public education), suspected I might be an undercover agent for the Immigration and Naturalization Service. I loathed the process of telephoning strangers to ask for interviews, and the rejections made it worse. Still, I persevered and eventually interviewed thirty-seven employers and twenty-three employees.5 I asked employers and employees alike about their varied experiences with paid domestic work, the specific job terms and how these were set, what they liked and disliked about the job arrangement, and basic demographic information. I conducted nearly all of the interviews in the respondents' homes—which means I drove great distances around Los Angeles County, visiting neighborhoods I might never otherwise see in the course of my daily life and wearing out a set of tires; a few took place at my home. Each interview lasted approximately two and a half hours, and the verbatim transcripts averaged about forty to fifty pages of single-spaced text. I read through them many times, selectively coded portions, and then created computer files to bring together pieces of interviews that addressed themes of interest to me. Nearly all of the interviews with employees were conducted in Spanish, and I translated into English only those portions that appear in the text.

Although I had no illusions about drawing a random sample of a universe about which so little is known, I knew I didn't want to confine interview respondents to self-selected groups, such as feminist university women who employ housecleaners, or Latinas who had already organized in one of Los Angeles' domestic worker organizations or cooperatives. These would have been easy pools of respondents, but I wanted to interview more heterogeneous groups of women. I therefore deliberately sought out women from different social and geographic locations in Los Angeles. For example, when I began to search for employer interviewees, I contacted a friend's mother—a liberal-leaning, Jewish retired teacher living on the West-side of Los Angeles; I subsequently interviewed several of her friends who lived in that vicinity and shared similar characteristics. I also began other small snowball samples that reflected different kinds of diversity by tapping into communities of, for example, young, white, well-to-do homemakers from a nursery school cooperative near the Hollywood Hills; middle-aged women living in a multiracial suburb deep in Los Angeles' San Gabriel Valley; and a younger group of career women, some of whom had children and some of whom didn't. This approach did not produce a representative sample (my method, for example, led me to only one interview with a male employer), but it allowed me to speak with employers from different walks of life, at different life stages, and with diverse opinions and experiences. As I requested interviews with employers, I also looked for a balance among the kinds of arrangement for paid domestic work, including respondents who hired, respectively, live-in nanny/housekeepers, live-out nanny/housekeepers, and weekly housecleaners.

I similarly recruited Latina immigrant domestic workers for the study I interviewed nannies whom I had met in the park or at bus stops, at presentations that I made in ESL (English as a second language) classes, and through referrals passed to me by friends or other interviewees; I even interviewed a woman who had left her “looking for work” card on my doorstep. These Latina immigrants, as Chapter 2 shows, are diverse in their national origins, in their ages, arid in the types of domestic work they do. With the exception of two sisters whom I interviewed together, I spoke with each domestic employee privately; and in addition to the questions mentioned above, I also asked them about their work and social lives before migrating to the United States, their family and social lives, and their future occupational aspirations. Cognizant of the precarious financial position of many of these women, and of the substantial time commitment required by my interviews, I initially tried to discreetly pass $25 or $30 in an envelope to each interview participant. Many of the women refused this money. In some cases, I succeeded in prevailing on them; in others, not. Finally, I settled on bringing to each interview a blooming plant, which I purchased at my local supermarket. Most women enjoy receiving flowers, and Latina domestic workers are no exception. In addition to the twenty-three nanny/housekeepers and housecleaners and the thirty-seven employers, I also formally interviewed three attorneys specializing in legal issues surrounding private paid domestic work and five individuals who owned or worked in domestic employment agencies. Altogether, I conducted in-depth, audiotaped interviews with sixty-eight people. And without my tape recorder, I spoke more casually with many more domestic workers, employers, and several organizers and attorneys. Throughout the text, pseudonyms are used for all employers, employees, and agency personnel, but not for the advocacy attorneys.

The interview materials are the most crucial source of information in this book. By using them, I have sought to enable the voices of employers and employees tc be heard. To be sure, this is not a kind of ventriloquism, as qualitative, interview research used to be viewed—with the ventriloquist (me) simply mouthing other people's stories. I am deliberately using their words to put forth a specific argument about contemporary paid domestic work. In postmodern anthropology the illusion is broken, and the power of the ventriloquist to select and form the dialogue is fully revealed: but those in the audience, who hear and interpret the dialogue, also have agency My position is that this is an interactive process, and the voices that emerge in the interviews, like other sources of information, provide us with only a partial view of the whole. In addition, it is important to note that much of what people reveal in interviews is shaped not only by their relationship to the interviewer but also by particulars and upheavals in their own lives at the time. The salience of these issues changes from day to day, week to week. For this reason, I have tried to avoid taking people's words out of context and to sketch, wherever possible, the proper setting for understanding the interviewee's experiences and perspectives.

Data from a survey questionnaire administered to 153 Latina immigrant domestic workers at a public park, at bus stops, and at evening ESL classes also inform this book. I administered the survey together with two research assistants, Gloria González-López and Ernestine Avila, who were then Ph.D. students. We went to downtown bus stops and to a busy, intracity bus terminal at 6 A.M. on Monday and Tuesday mornings (a time when many live-in workers are returning to their jobs); and we collected other responses at a popular Westside park where nannies bring young children in the middle of weekday mornings and at evening English classes in Hollywood. This was not a random, representative survey. It drew on women employed in the tonier neighborhoods of Los Angeles' West-side, and it left out many Latina domestic workers who speak English well and who drive their own cars to work. Still, it sketches a portrait and provides us with very particular information not available through the census or Labor Department statistics. The survey collected basic demographic information, such as the worker's country of origin, number of years in the United States, marital status, number of children and where they reside, previous occupational experiences, and, most important, information on wages and hours. For this study, I've also consulted the Census Public Use Microdata Sample for Los Angeles, but because both this occupation and the immigrant population generally are largely underrepresented in the census, I do not wholly rely on those indicators.

Finally, the research for this book also draws on limited ethnographic observations made in public and private sites. I spoke to, listened to, and passed time with Latina domestic workers in various settings: at public parks, on buses, at bus kiosks near downtown, in west Los Angeles and in Beverly Hills, at the now-defunct Labor Defense Network legal clinics—where Latina and Latino immigrants doing all kinds of work came to seek legal remedies to job problems—in the waiting rooms of domestic employment agencies, at meetings and informal social gatherings of the Domestic Workers' Association of CHIRLA, and at the information and outreach program that was the DWA's precursor. Rather than limit myself to one method or one source of information, I have explored many different ways of knowing about this occupation.

OVERVIEW

Chapter 1 situates contemporary paid domestic work in place and time and explains why, as the twentieth century ended, paid domestic work became a growth occupation. Besides noting the macrostructural, demographic, and cultural forces that have spurred this occupational growth, the chapter also contrasts historical with contemporary racialization of paid domestic work in the United States, underscoring why the job is still held in low regard. Noting some recent trends in the international migration of labor, I argue that the migration and employment of domestic workers in the United States today is distinctively laissez-faire and forms part of what I call the new world domestic order. Beginning with the observation that paid domestic work is organized in different ways, Chapter 2 provides a close-up portrait of some of the domestic employees whom I interviewed. It describes how the job is experienced by live-in nanny/housekeepers, live-out nanny/housekeepers, and housecleaners, focusing on a few of the women and using data from the nonrandom survey of 153 Latina domestic workers to sketch their broader demographic and social profile.

Part 2 includes three chapters that examine the ways in which Latina immigrants enter and exit domestic jobs in Los Angeles. Chapter 3, on informal network hiring, focuses on the formation and inner workings of employer and employee networks. I argue that supply and demand alone are not enough: mechanisms for joining the two must be provided. The labor market for paid domestic work is constructed through the social network reference system, whose processes are important not only in job placement but also in effecting some job standardization, however imperfect. Chapter 4 examines the formalization of recruitment and hiring in domestic employment agencies, and Chapter 5 examines the various ways in which domestic jobs end. Both hiring practices and approaches to job termination reveal that paid domestic work is often not recognized or treated as a “real job.”

Part 3 examines social relations on the job. Chapter 6 focuses on labor control: the ability of employers to obtain the desired work behavior from their domestic employees, and the ways in which housecleaners and nanny/housekeepers, in turn, comply, resist, and negotiate. While there are broadly shared understandings of these jobs, the tasks are diffuse and there are no written standards to specify which services will be performed, or how they will be executed. Here's the paradox: many domestic workers want clear, fair directives, but their employers often shy away from defining the tasks they want performed. Because of the structure of the different jobs, the approaches of housecleaners and nanny/housekeepers to time and tasks vary; and their employers, of disparate generations and with various relationships to domestic life, also innovate different approaches to matters of labor control.

Chapter 7 concentrates on the topic that has drawn the most attention in the study of paid domestic work, personalism and maternalism. Many Latina immigrants currently employed in private domestic work in Los Angeles express their strong preference for employers who interact personalistically with them, while many of their employers say they would rather not engage in these sorts of relationships. To explain this gap, which contradicts the findings and analyses of previous studies, I distinguish personalism from maternalism and draw attention to the social locations of both employees and their employers. In Chapter 8,1 review existent labor regulations relevant to paid domestic work, and I explore different pathways to fairer job standards. As an advocate of occupational upgrading, not abolition, I consider how legislation, filing for back wage claims, and collective organizing (in Los Angeles, specifically the DWA), can help achieve this goal.

While this book focuses on private paid domestic work in Los Angeles, California, the occupation is expanding throughout the world. In the newly industrialized nations of Asia, in Europe, and in parts of Africa and Latin America, just as in the United States, many private domestic workers are women who have crossed nation-state borders.6 For these migrant women, globalization has intensified inequalities that require strategies for change.

This book is not neutral: it is undergirded and motivated by a modernist belief that a fuller appreciation of the experiences and perspectives of both private domestic workers and their employees can lead to positive change. As we come to understand the social world of paid domestic work, which takes form within the context of broader global and legal structures, what is often seen as only private will begin to be made public and thus able to inform efforts to achieve social justice.