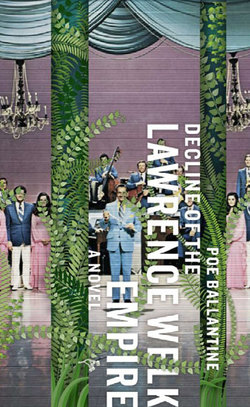

Читать книгу Decline of the Lawrence Welk Empire - Poe Ballantine - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление8.

IN THE MORNING I FILE AT UNEMPLOYMENT, WHERE I’M sent five miles away to the magnificent five-star Broadmoor Hotel, nestled in the foothills against the snow capped mountains. I’ve never heard of this place. It’s gorgeous, with a golf course and a ski run and five restaurants. The personnel director glancing over my application asks me if I’d prefer to be a kitchen runner or work with the air-conditioning and heating team. I vote kitchen job because it sounds warmer, plus probably a meal. What are the odds of getting a job on your first try and then at a five-star hotel? And the next morning I’m running trays of food up and down the stairs, and I’m right about the free meal, schnitzel, peas and pearl onions, and new potatoes in parsley and cream.

From work that afternoon I hitchhike straight to the King Soopers on Uintah, then I stop at the liquor store. It’s dark by the time I get home, and I’m exhausted but I have a job, beer, beans and franks, a roof over my head. And I love this little apartment. When I open the screen door the creak of the hinge seems to announce: “Here he is.”

With my first paycheck I have a chat with Mr. Mondragon, my surprised landlord (he didn’t know Gloria had run off to Gunnison with a bull rider) and manage to keep my one-bedroom apartment, though I have to dish up another fifty for security. Mondragon is pleased I’m employed at the Broadmoor. “Classy joint,” he says. “They pay pretty good, huh?”

“Not that well, no.”

“How long you planning to stay?”

“Oh, I’ll be leaving in the spring,” I say.

“You don’t like Colorado Springs?”

“I like it fine,” I say. “But I’m a traveler.”

He gives a savvy nod.

In the meantime, the weather has improved. And Colorado Springs—an undiscovered dulcimer village tucked into those lavender-smudged Rocky Mountains that have inspired so many poets such as John Denver—is quite tolerable. The job is a dead end, suitable for high school dropouts and teenagers with drug problems, but after only two weeks of my running food up and down the stairs from the main kitchen, a Tavern cook leaves and Chef Bruneaux, the Tavern chef, asks me if I’d like to take the cook’s place. I’m elated. Plus there’s a quarter-an-hour raise. I’ve always wanted to know how to cook.

And I seem to have a flair. I like the butter and the heat, the burns and sharp knives, the lunacy of the onslaught of waiters and waitresses during the rush, the shouting and desperation, the heavy, starched uniform and the puffy French hat. Except for the hat, cooking, I imagine, must be like war. Since most of the food is prepared upstairs and we merely spoon it back out of a steam table, omelets are the hardest detail to master. I’m a lunch cook, yes, but we make dozens of omelets daily, caviar and sour cream, Monterey jack and mushroom, Denver, bacon, avocado, shallot and crab omelets. It takes me about a week flipping scorched and runny eggs everywhere but back into the pan before I get good. At the right temperature the whipped egg and milk mixture foams up the pan sides like cake batter. Ferran, the executive chef, a waddling old French autocrat, looms over us. Rumor has it that any cook who even vaguely browns an omelet and dares to serve it will be dismissed. We’ve got these hot-handled steel French pans that you have to rub out with salt and half the time the eggs stick anyway, so I buy one of the first non-stick pans of the day, a T-Fal, and all the other cooks look upon me with reproach (see envy), but watch me flip that omelet without a snag or an oath every time. Ferran grumbles, but he can’t argue with a first-rate, cake-high, daisy yellow omelet. I’m more proud of my ability to make fabulous omelets than any A I ever got on a psychology exam.

Soon I’m transferred to dinner cook. Twenty-five cents more an hour and not so many omelets, but about as many tickets. The Tavern is the busiest of the five restaurants at the grand old Broadmoor. Our dining room (with the original Toulouse-Lautrecs hanging from the walls and Frank Fanelli and his Orchestra churning out the dance numbers live on stage) holds at least two hundred guests, and sometimes we turn the room over three times. Famous people come here too. A waiter will rush lisping into the kitchen, “Peggy Fleming is out there!” Not that I’m excited about celebrities, especially ice-skaters. As a matter of fact, I never leave the kitchen to look out over the glittering sea of wealthy diners. I don’t admire the rich, who merely subjugate others for their comfort and amusement. I hold them responsible for the plight of America and the wastrel example they set for the rest of us. America is a corrupt and dissolving civilization whose pride has always been reserved for the wealthy and the famous, the so-called winners. I prefer the culture of poverty, from which all good things—humility, honesty, the words of Christ and Lincoln, rock music, and French onion soup—have evolved.

Dinner cook suits me. I can sleep late, stay up late, read books, lounge in front of the radio, make entries in my journal, sit in one of twenty pieces of furniture, and blow smoke rings at the ceiling. I’ve gotten into the habit of checking out three or four books a week from the library down the street. The gummy and lightweight ball of gossamer that passes for my brain has at long last, without the constant assault of recreational drugs, begun to awaken and reform. Late at night my noisy neighbors have all drifted off to sleep. When I was a friendless, asthmatic boy I used to sit in bed and read all night, my only pure satisfaction in life.

The only bad part about cooking the afternoon shift is hitchhiking home in the dark. More than once I’ve had to walk. And coming to work I’ve been late a couple of times too. And now in December it’s getting cold. The winter snows have begun in earnest. I’ve tried to avoid it, but at last, reluctantly, I enter a car lot. I don’t like cars. They’re obscene contraptions, fossil-fuel furnaces. But I’m not going to hitchhike or walk anymore through the blizzards of midnight. I find a Fiat that I like. It’s only a thousand bucks. It’s a small car. It won’t pollute too much.

The salesman is a ruddy man in a down jacket and green slacks who smells vigorously of cinnamon gum. He strolls over. “Nice car, huh?”

“Can I drive it?”

He positions his hands as if his thumbs are hooked into suspenders. “Key’s in the ignition,” he says.

This is my kind of car, I think, whipping it around the block. I’ve always seen myself, if I had to see myself in a car, in a European sports car. They’re French, aren’t they, Fiats?

In the salesman’s office he creaks back in his chair, thumbs now hooked in the invisible suspenders of his Arrow sports shirt, and begins to amiably shake his head. “Can’t sell you the Fiat,” he says.

“Why not?”

“You got no credit. You been working only two months.”

“What am I going to do?” I say, feeling tears well. “ I need a car.”

“Tell you what,” he says, crossing his feet up on the desk and cradling the back of his head in his hands. “I’ll sell you the Vega.”

“The VEGA?” I look outside. A few flakes zigzag past the glass. I already saw the Vega. It’s a Kaamback, a station wagon, and outside of a crumpled fender and a cracked windshield it isn’t in bad shape, but I know that Vegas are terrible cars. The cocaine addicts who assemble them in Detroit put rocks in the wheel covers because they only make nine times an hour more than I do. “But I don’t want the Vega,” I say.

“Sorry,” he says. “We’ll finance you for the Vega but not the Fiat.”

“How much is the Vega?”

“Thousand dollars.”

“Same price as the Fiat,” I say. “I don’t get it.”

“We’ll extend you the credit,” he says, “but you’ll have to take the Vega.”

I decide to take the Vega. I know after working only ten weeks with a job that pays only fifty cents over minimum that I’ll be lucky to find anyone who will finance me. Anyway, I’m leaving soon. It won’t matter. I sign on the dotted line and drive my Vega off the lot. It isn’t so bad. Nice radio. Automatic transmission. Plaid vinyl seats. Two blocks out the driveway it dies. I stomp back to the lot. The flummoxed salesman has it towed back to the garage. “It’s a gas-sending unit,” he explains half an hour later, with a slap on my back. “You shouldn’t have any more trouble with it.”

“Right,” I grumble, and I drive it away again, knowing I’ll be back, knowing I’ve been screwed. They sold me the Vega because I was the only fool on earth who would buy it. A man with any backbone would’ve fought for the Fiat.