Читать книгу God Is Always Near - Pope Francis - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Rede Globo

For a Church That Is Near

Gerson Camarotti

Thursday, July 25, 2013

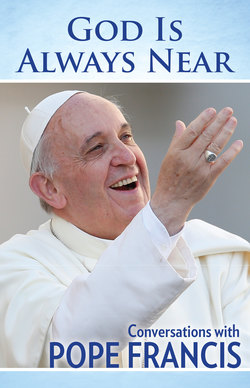

Pope Francis’s interview with Rede Globo during his Brazil trip received little attention in the Western media at the time, given the focus on the pope’s memorable activities at World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro. The interview, however, provided several key insights into why he chose a humble Ford Focus as his main vehicle in Rome and also why he chose to live at the Casa Santa Marta, the Vatican hotel, instead of the Apostolic Palace.

His discussion of the phenomenon of Catholics leaving for Pentecostal and evangelical churches is also significant, especially his emphasis on the need for priests—for the Church—to be close to the people. “Closeness,” Pope Francis tells his interviewer, “is one of the pastoral models for the Church today.”

During his trip to Rio de Janeiro, the Pope granted a lengthy interview in Spanish to Gerson Camarotti of GloboNews, which aired on Sunday, July 28, during a program entitled Fantástico that was broadcast over the Brazilian network, Rede Globo. An Italian translation appeared in the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, on August 1, 2013. The following is an English translation of that interview, which was conducted in Spanish and Portuguese.

Pope Francis, you arrived in Brazil and were warmly welcomed by the people of Brazil. There is a historic rivalry between Brazil and Argentina, at least in regard to football. What was your reaction to such a gesture of affection?

I felt welcomed with affection that I have never experienced—a very warm, warm welcome. The Brazilian people have a big heart. I think the rivalry is now a thing of the past, because we have reached a deal: the pope is Argentine and God is Brazilian.

It’s a great solution, isn’t it, Holy Father?

I felt very welcome, with great affection.

Holy Father, you used a very simple car here in Brazil. People say that you have even reprimanded priests who use luxury cars around the world. You also decided to reside at the Santa Marta guesthouse [the Vatican hotel built chiefly to house the cardinals during a conclave]. Is this simplicity a new direction that priests, bishops, and cardinals have to follow?

These are two different things that are distinct and need to be explained. The car that I used here is very similar to the one I use in Rome. In Rome, I use a blue Ford Focus, a simple car that anyone might use. In this regard, I think we have to give witness to a certain degree of simplicity, I would even say of poverty. Our people demand poverty from our priests. They demand it in the best sense of the word. People feel sad when we, who are consecrated, are attached to money. It’s not a good thing. It really isn’t a good example that a priest should have the latest model or the latest brand. I say this to priests; in Buenos Aires, I used to say it all the time: Parish priests need to have a car because there are thousands of things that you need to do in a parish, and you need to get around. But it must be an unpretentious car. So much for the car!

As regards my decision to live at Santa Marta, it was not so much for reasons of simplicity, because the papal apartment, though big, is not luxurious. It’s nice, but not as luxurious as the library on the floor below, where you receive people, with its very beautiful works of art. It’s pretty simple. However, my decision to live in Santa Marta is based on how I am. I cannot live alone. I cannot live isolated. I need contact with people. So, I usually explain it like this: I decided to stay at Santa Marta for psychological reasons, so I wouldn’t suffer the loneliness, which is not good for me, and also for reasons of poverty, because otherwise I would have to pay a psychiatrist a lot of money. That wouldn’t be good.

It’s to be with people. Santa Marta is a home that is home to about forty bishops and priests who work for the Holy See. It has 130 rooms, more or less, and priests, bishops, cardinals, and laypeople who are guests in Rome reside there. There, I have breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the dining room. I always meet all different kinds of people, which is good for me. This is the reason.

Then, too, there is a general rule. I believe God is calling us at this time to greater simplicity. It’s an interior thing that he is asking of the Church. The council had already drawn our attention to this—a life that is simpler and poorer. This is the general direction. I don’t know if I answered your questions about the car, Santa Marta, and the general direction. Did I?

I have been very struck by the fact that you will be canonizing Pope John XXIII. Is he a model that you wish to hold up?

I believe that the two popes who will be canonized during the same ceremony are two models of the Church as it moves on. Both have borne witness to renewal in the Church, in continuity with the tradition of the Church. Both have opened doors to the future. John XXIII opened the door to the [Second Vatican] Council, which continues to inspire us today and which has not been put entirely into practice. A council, in order to be put into practice, takes about one hundred years, which means that we are halfway along the way. John Paul II took up his suitcase and traveled around the world. A missionary, he set forth to proclaim. He was a missionary. They are two great men from the Church today. For this reason, it will be a pleasure for me to see the Church proclaim them saints on the same day and in the same ceremony. [The two popes were canonized on April 27, 2014.]

It is highly symbolic, which I, too, consider very important. Holy Father, when you arrived in Rio de Janeiro, a lot of mistakes were made in terms of security. Your car was in the middle of the crowd. Were you afraid? What was your feeling at that moment?

I wasn’t afraid. I’m a little reckless, but I’m not afraid. I know that no one dies before his time. When my time comes, what God wills, will be. Before we left, we went to see the popemobile that was going to be sent there. It had so many windows! If you’re going to see someone you love so much, some good friends with whom you want to be in touch, are you going to visit them in a glass case? No! I couldn’t go to see people with such big hearts in a glass case. When I go out on the streets in the car, I roll down the window so I can put my hand out to greet people. It’s all or nothing. Either a person makes the journey and communicates with the people like it should be done, or doesn’t make it at all. Halfhearted communication doesn’t do any good.

I’m grateful—and on this point I want to be very clear—for the Vatican security personnel, for the way in which they prepared my visit, for the zeal that they demonstrated. And I am also grateful for the security personnel in Brazil. I am very grateful to them because even here they have been taking great care of me, and they did not want anything unpleasant to happen to me. It can happen; someone can take a shot at me. It can happen. Both security forces worked very well. But both realize that I am undisciplined in this regard. I don’t do it because I want to be some kind of enfant terrible. I simply do it because I have come to visit the people, and I want to treat them like people. I want to touch them.

Your good friend, the Brazilian Cardinal Cláudio Hummes, has spoken on several occasions of your concern for the loss of so many of the faithful here on this continent, especially in Brazil, who are joining other denominations, mainly evangelical ones. I ask you, therefore, why this happens, and what can be done?

I don’t know the causes or the percentages. I heard a lot about this issue—this concern for the people who are leaving—during two synods of bishops, for sure during the synod in 2001 and then in another synod. I do not know enough about life in Brazil to give an answer. I believe that Cardinal Hummes was one of those who spoke about it, but I’m not sure of that. If you say he has spoken about it, it’s because you know.

I can’t explain it. There is one thing I can imagine. For me it is essential that the Church be close to the people. The Church is mother, and neither you nor I know of any mother who mothers from a distance by letter. A mother gives affection, touches, [and] kisses, and loves. When the Church, occupied in a thousand different ways, neglects this feeling of closeness, it forgets about it and communicates only through documents. It’s like a mother communicating with her son by letter from a distance. I do not know if this has happened in Brazil. I don’t know. But I do know that this is exactly what happened in some places in Argentina: a lack of closeness, of priests. There is a shortage of priests, so you are left with a country without enough priests. People are seeking; they need the Gospel.

A priest told me that he had gone as a missionary to a city in the south of Argentina, where there hadn’t been a priest for almost twenty years. Obviously, people went to listen to this priest because they experienced the need to hear God’s word. When he got there, a very well-educated lady told him: “I am angry with the Church since she abandoned us. Now I go to Sunday worship services to listen to the pastor, because he is the one who has been feeding our faith all this time.” Closeness is lacking. They talked about this, the priest heard her out, and when they were about to say goodbye, she said to him: “Father, wait a moment. Come here.” She took him to a closet. She opened the closet and inside was the image of the Virgin Mary. She said, “Father, I keep it hidden so that my pastor doesn’t see it.”

That woman went regularly to that pastor and respected him. He spoke to her about God and she listened and accepted what he had to say, because she didn’t have anyone else to minister to her. She kept her roots hidden in a closet. Yet, she still had them. This phenomenon is perhaps more widespread. Such a story often shows me the tragedy of such a flight, of such a change. Closeness is lacking. Going back to my earlier image, a mother does this with her son: she cares for him, kisses him, caresses him, and feeds him—but not from a distance.

We must be close, isn’t that so? Much closer!

Closeness is one of the pastoral models for the Church today. I want a Church that is close by.

When you were elected in the conclave, the Roman Curia was the target of criticism, even criticism from various cardinals. And the feeling I perceived, at least from one cardinal, with whom I spoke, was of change. Was my feeling correct?

I’ll digress for a moment. When I was elected, my friend, Cardinal Hummes, was next to me, because according to the order of precedence we were one behind the other. He said something to me that was very helpful: “Do not forget the poor.” How beautiful! The Roman Curia has always been criticized, at times more and at times less. The Curia is ripe for criticism, given the fact that it has to resolve so many things, some which people like and others that they do not like. Some of their procedures [are] carried out well, while others are poorly implemented, as is the case with every organization.

I would say this. There are a lot of saints in the Roman Curia—saintly cardinals, saintly bishops, priests, religious, lay-people, and people of God who love the Church. This is what people don’t see. A tree that falls in a forest where there is a lot of growth makes a lot more noise than the trees that are growing! The noise from these scandals is louder. Currently, we are dealing with one: the scandal of a bishop who has transferred ten million or twenty million dollars. This man isn’t doing the Church a favor, is he? We have to admit that this man has acted badly, and the Church must give him the punishment he deserves because he did act badly. There are such cases.

Before the conclave, the so-called general congregations took place. The cardinals had a week of meetings. There, we talked clearly about these problems. We discussed everything since we were there alone to see what was really going on and to trace the portrait of the future pope. Serious problems emerged, some of which are rooted in part in everything you already know, such as Vatileaks. There were problems with scandals. But there also continue to be saints, those men who have given and continue to give their lives for the Church in a silent way yet with apostolic zeal.

There was also talk of certain functional reforms that needed to be carried out. It’s true. The new pope was asked to form a commission of outsiders to study the organizational problems of the Roman Curia. A month after my election, I appointed such a commission of eight cardinals, one from every continent—with two for America, one for the North and one for the South—as well as a coordinator, who is also from Latin America, and a secretary who is Italian.

The commission has begun its work, listening to the opinions of the bishops, to the bishops’ conferences, in order to become familiar with how these reforms should appear within the dynamic of collegiality. A lot of documents have already arrived which we obtained from the members of this commission, which are currently being circulated. We will have our first official meeting from October 1-3 [in 2013]. There, we will examine some different models. I don’t think anything definitive will result at that time because curial reform is a very serious matter. I will see the proposals. If the proposals are very serious, they will have to be developed. I estimate that we’ll need two or three more meetings before there is any kind of reform.

On the other hand, some theologians have said—in Latin, and I’m not sure if it was in the Middle Ages—Ecclesia semper reformanda: “The Church always needs to be reformed.” Otherwise, it lags behind, not only because of scandals like Vatileaks, which everyone knows about, but because the Church always needs to be reformed. There are things that worked in the last century, which worked in past ages and from other vantage points, which no longer work and need to be adapted. The Church is a dynamic organism that responds to life’s circumstances. All of this is something that was requested during the meetings of cardinals before the conclave. We spoke in very clear terms, and some very clear and concrete proposals were made. We will continue along these lines. I don’t know if I answered your question.

You responded very well, very thoroughly. What is your message for the youth of Brazil? Your message comes at a time when young people are protesting in the streets of Brazil in order to register their dissatisfaction in a very strong way. What message do you have for these young people?

First of all, I need to make it clear that I don’t know the reasons why these young people are protesting. So if I say something without clarifying this, I would be making a mistake; I would be making a mistake to everyone, because I would be giving an opinion without knowing the facts. Frankly, I don’t know exactly why these young people are protesting. Second, I’m not happy with a young person who does not protest, because young people dream of a utopia, and a utopia is not always a bad thing. A utopia is a breath and a look to the future. It’s true that a young person is fresh to life and has less life experience. Sometimes life’s experiences can hold us back. However, young people have greater freshness to say what they want to say. Youths are basically nonconformists. This is wonderful! This is something that all young people have in common.

In general, I would have to say that you need to listen to young people, give them room to express themselves, yet exercise a concern for them so that they do not end up being manipulated. Insofar as there is human trafficking—slave labor and so many forms of human trafficking—I would dare to add one more thing without offending anyone: There are people who target these young people to manipulate this hope, this non conformism, thereby ruining the lives of young people. Therefore, we need to be attentive to this manipulation of our youths. Young people need to be heard. Pay attention to them! A family, a father, and a mother who do not listen to their young son end up isolating him and stirring up sadness in his soul, not taking any risks themselves. Young people have a wealth to offer, but clearly lack experience. Yet, we have to listen to them and protect them from any strange form of manipulation, whether it be ideological or sociological. We must listen to them and give them room to sound off.

This leads me to another issue that I spoke about today in the cathedral when I met with the group of young people from Argentina—a group of representatives who had come to present me with their credentials. I told them that the world in which we live today has fallen into a fierce idolatry of money. This creates a global policy that is characterized by the prominence of wealth. Today, money is what controls us. The result is an economic-centered global policy that does not have any ethical controls; an economic policy that is sufficient unto itself and that organizes our social structures as it seems fit.

What happens then? When such a world of fierce idolatry of money reigns over us, we focus a lot on those at its center. But those on the margins of society, those at its limits, are neglected, uncared for, or discarded. So far we have clearly seen how the elderly are left aside. There is a whole philosophy for discarding the elderly. There’s no need to do so. It’s nonproductive. Even our young people do not produce that much because there is a potential that needs to be formed. And now we are seeing that those at the other end of the spectrum, our young people, are about to be left aside.

The high rate of youth unemployment in Europe is alarming. I won’t make a list of the countries of Europe, but I will give two examples of serious unemployment in these two wealthy countries in Europe. In one, the index of unemployment is 25 percent of overall unemployment. But in this very same country, the index of youth unemployment is 43 or 44 percent. That means that 43 or 44 percent of the youth of this country are unemployed! In another country, with an index of over 30 percent overall unemployment, unemployment among young people has already exceeded 50 percent. We are facing a growing phenomenon of young people being “discarded.” In order to support such a global political model, we simply discard those on its margins. Curiously, we discard those that hold the promise for the future, because the future lies in the hands of our young people since they will be the ones who carry out this future, as well as the elderly, who need to pass on their wisdom to our youths. By discarding both, the world will collapse.

I do not know if I’m making myself clear. A humanistic ethic is missing throughout the world. I’m talking about a worldwide problem—on a worldwide level, as I more or less know it. I’m not very familiar with details regarding this country. And if you give me a minute more, I will say something else regarding this issue. In the twelfth century, there was a very good rabbi who was a writer. Through stories, he explained moral problems to his community that were in some passages of the Bible. Once, he explained the Tower of Babel to them. This medieval rabbi, from the twelfth century, explained it in the following terms: What was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Why did God punish them? To build the tower, they needed to make bricks: cart the mud, cut the straw, mix the two together, cut them, dry them, cook them, and then take them up to the top of the tower. This is how it was built. If a brick fell, it was a national catastrophe. If a worker fell, nothing happened.

Today there are children who have nothing to eat in this world, children who are dying of hunger and malnutrition. Just look at photographs of some of the places in this world. There are sick people who do not have access to health care. There are men and women who are beggars who are dying in the cold of winter. There are children who do not receive an education. All this does not make the news. Yet, when the stock exchange loses three or four points in a few capitals of the world, it’s a worldwide catastrophe. Do you understand what I am saying? This is the tragedy of this inhumane humanism that we are experiencing. For this reason, we need to come to the aid of those living on the margins—children and young people—without falling into a global mentality of indifference with respect to these two extremes, who are the future of a nation.

Excuse me if I have dwelt too much on this and have spoken too much. By doing so, you have my opinion. What’s happening with young people in Brazil? I don’t know. But, please, do not manipulate them. Listen to them, because it is a worldwide phenomenon, which extends far beyond Brazil.

Very interesting! That’s a very deep thought. I’d like to ask you one last thing. What is your message you’d like to give to Brazilians who are Catholic as well as to Brazilians who are not Catholic, who belong to other religions. For example, Rabbi [Abraham] Skorka, your friend from Buenos Aires, was here. What message would you leave to a country like Brazil?

I think we should promote a culture of encounter throughout the world, so that everyone may experience the need to impart ethical values to mankind, which are needed so much today, and to protect this human reality. In this regard, I think it is important that everyone works together for others, pruning away our selfishness and working for others according to the values of the faith, which is ours. Every denomination has its own beliefs, but, according to the values that are part of this faith, we need to work for those around us. Moreover, we need to meet together in order to work together for others. If there is a child who is hungry and who is not receiving an education, what should matter to us is putting an end to this hunger and making sure he receives an education. It doesn’t matter whether those who provide this education are Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, or Jews. I don’t care. What matters is that they be educated and that they be nourished.

The urgency today is such that we cannot quarrel among ourselves to the expense of others. We must first work together for those around us, then talk together among ourselves in a deep way, with each one giving witness to their own faith, trying to understand each other, of course. But today, above all, closeness is urgently needed, a need to step out of our comfort zone in order to resolve the terrible problems that exist in today’s world. I believe that the different religions or the different denominations—I prefer to speak about different denominations—cannot sleep peacefully as long as there is even one child who is dying of hunger, one child who goes without an education, one young person or one elderly person who goes without medical attention. Nevertheless, the work of these religions, these denominations is not one of charity. This is true. As regards at least our Catholic faith, our Christian faith, we will be judged by these works of mercy.

It will serve no purpose to talk about our theologies if we do not have the closeness to others to go out to help and support others, especially in this world where so many people are falling from the tower and no one is saying anything.

Thank you, Pope Francis. Thank you for the interview and for your message for Brazil.

I thank you for your kindness. This is a wonderful people. Wonderful!

In spite of the cold weather that welcomed you?

No, I’m from the south. I’m familiar with the cold weather in Buenos Aires. This is normal autumn weather.

So you’re not amazed by the cold? Brazil is more tropical than Argentina. Didn’t you expect Brazil to be a little warmer?

No. Maybe I did expect it to be a bit warmer, but I haven’t felt the cold.