Читать книгу Tamed By a Bear - Priscilla Stuckey - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Chris was a woman of near sixty, born and raised in the Midwest, who in her early forties, with two decades of a business career behind her, had been called to work with what she called Spirit Helpers. Because the friend who had recommended Chris to me was a down-to-earth and gutsy woman, and especially because this same friend had been a Rhodes Scholar, I figured Chris couldn’t be too much of a slouch.

On the phone with Chris for the first time, months before, I’d heard a calm and thoughtful voice, warm and reassuring but no-nonsense. At the time I’d just finished writing the book, and I needed clarity about what was to happen next—all the questions I’d let slide during the writing process. Plus I was dreading the upcoming months of waiting until the book would finally emerge. An edge had crept into my voice—impatient, self-justifying; I can hear it now in the recordings of those sessions, though at the time I was anything but aware of it.

Chris practiced a straightforward kind of conversation with spirit. She said that each person is watched over by their own Spirit Helper, often an animal or other being, who loves and supports a person throughout their life and who provides a face—a point of contact, a relationship—for connecting with spirit. Chris called Helpers “ambassadors of the Living Spirit”; they are always ready to share advice and wisdom from a source beyond human knowing if only a person gets up the courage to ask for it. Chris, who had been tuning her ear to Helpers for twenty years, was practiced in hearing each person’s Helper, and on the phone she acted as a translator, listening quietly for a few moments and then passing along what she’d heard.

From the start, more than a year earlier, I had loved those phone sessions. I took to them like a duckling to water, wading onto the surface and bobbing happily. In each session I felt deeply listened to, the desires of my heart known and addressed, often without my having to articulate them. Every suggestion for the next steps to take arrived in down-to-earth language, with words that often carried the ring of my own vocabulary. Each session gave me the sense that help is available for this murky thing called life. I felt deeply nourished.

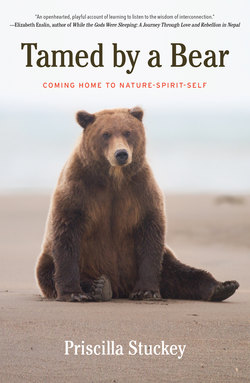

My Helper, whom Chris identified as Bear, got down to business right away. I was given affirmation for the path I was taking as well as suggestions for how to walk in it more effectively. Bear did hint ever so gently that when it came to listening to spirit I had a great deal more to learn—that even though I’d just written a whole book about spirit in nature, I had barely scratched the surface. “If one believes that help from a source outside human knowing is not possible, it will be a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Bear said one day, an impersonal generality that gives me a chuckle because now I can hear the clue that Bear was offering—politely, obliquely—about my beliefs and my next step. But at the time I was tone-deaf to his nuances.

I did have to agree with Bear’s point, however. For no matter how much my heart was feasting on the sessions, my mind was drumming it in to me, with the rat-a-tat of a woodpecker at a tree, that this Helper business was likely all a crock. Communicating directly with anything unseen is not possible, it said, and to think otherwise suggests some serious misperceptions of reality.

It’s not that I didn’t believe that something greater than human wisdom exists. I liked to hint now and then, as people do, about “the Universe,” a word satisfyingly vague, not like God or spirit or any of the old words belonging to religions we had left behind or now regarded—often for good reason—with mistrust.

But to speak directly with that Universe? Let alone in a conversational, friendly way? Not possible. What happened in those sessions offended every rational notion I held dear.

For one thing, there was that word shamanism. It was the term Chris used to describe her path, but it made me wince. I was aware how contentious it is, how it triggers pain for every Native person I have ever met or whose writings I have read. Shaman is a Tungus word—from the northern Indigenous peoples of Siberia—to name the person who keeps the human community safe and healthy by communicating with all those who are not human, such as the animals or the land or the deceased. Decades ago, white anthropologists took the word and applied it to any Indigenous nature-based healer and spirit worker they found anywhere in the world. So when a white person calls themselves a shaman, using that Indigenous term, what Indians usually hear is that the white person is trying to steal or at least copy Indigenous wisdom, Indigenous sacred traditions, Indigenous ways. It’s the whole of colonialism summed up in a single word.

“Why wouldn’t people just call themselves healers? Or ministers? Or soul-doctors—something like that?” an Indian friend of mine asked, staring sharply at me, when I brought it up with her. “Why do you have to use an Indigenous word?” It was a good question.

Then there was that translating business. Chris said she heard a spirit-being talking with her, giving her things to say, but how did she know it wasn’t her own voice? I didn’t for a moment think she was trying to make it up—she had far too much integrity for that—but neither did I think it was possible to hear across the great divide between the visible and the invisible, at least not without the message getting considerably skewed by the messenger. Maybe spirit does flow like pure water, but doesn’t every pitcher change the water’s shape? A person’s own physiology, their personality, their social context, their history—it all bends what they hear, doesn’t it?

Not to mention how easy it is to fool ourselves. Perception is such a shifty character! A shape-shifting octopus, now rough-skinned and blotchy on the mottled reef, now lifting off in a burst of inky darkness and smooth writhing limbs. We thought we knew what we were seeing, but the reality wasn’t what we saw. I’d long ago heard the parable of the snake from centuries-old Vedanta. A man walking along a road at dusk sees a snake and runs in great fear. But the next day at noon, coming to the same point in the road, he sees it was not a snake at all but only a coil of rope. Snake or rope? It can be devilishly hard to tell. “Now we see through a glass, darkly,” wrote the apostle Paul to the ancient Corinthians, which pretty much summed up my own view on the matter. I may have yearned for reality to be different, but the truth was—as my industrious woodpecker of a mind never ceased to remind me—that knowledge beyond the world of the five senses is impossible, and even here in this tactile world so much depends on your perspective, your point of view.

And then there was the biggest bugaboo of all: How could I trust anyone who claimed to speak words from God? After decades of studying religion, I was aware that recorded history, at least in the parts of the world I knew best, might well be written as a single ginormous argument between people on one side—individuals, groups, nations—saying, “God told us this!” and on the other side, “No! God told us that!” All the murder, rape, and pillage committed in the name of the divine, the forced conversions and slavery imposed through supposedly divine orders—it all took place side by side with kindness to strangers, sharing with the poor, and humbleness of heart, virtues also supposedly recommended by that same divine. So how could I possibly believe anyone’s claims to hear the “real” God? Like most modern people, I was sensitive to any whiff of “God said this,” and I regarded all such claims with a big dose of skepticism. To be perfectly honest, I discounted them all. Every last one. New Agers who claimed to hear Spirit Guides or Helpers were, to my mind, even less trustworthy. For no person, as far as I knew, could really hear God. There was no Extendable Ear reaching to heaven.

All of which left me living a huge contradiction, as even I had to admit. During book readings I was talking with audiences about how wonderful life could become if only we listened to animals, trees, and Earth more deeply, and in between trips I would sign up for more sessions of listening, through Chris, to my animal Spirit Helper. Yet, though Bear said during those sessions that I had a facility for hearing the Helpers, and though Bear recommended that I allow my connection with spirit to deepen and flourish, for without that connection a person walks crooked through life—a hitch in their step—and though Bear said plainly that one of my contributions in life would have to do with listening to wisdom from another realm and offering it to others, I didn’t have confidence in any of what I heard. I couldn’t bring myself to believe it was real.

Though I was enjoying the sessions with Chris immensely, I was having a hard time taking them at all seriously.