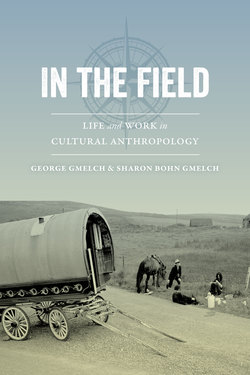

Читать книгу In the Field - Prof. George Gmelch - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

First Fieldwork

Irish Travellers

Our first, and longest, fieldwork engagement has been with Irish Travellers, an indigenous nomadic group similar to the Roma and other Gypsy populations. Anthropologists often maintain long-term relationships with the people they first study, and that has been true for us. George and I began working with Travellers in 1971 when, as a married couple in our twenties, we moved into a camp on the outskirts of Dublin to begin the fieldwork that would form the basis of our doctoral dissertations. We left the field thirteen months later to write up our observations but returned regularly through the 1980s and again in 2001 and 2011. In between, we maintained contact with some Travellers through occasional letters and holiday cards and, later, e-mail. In chapter 12, I discuss our return in 2011 when we brought back hundreds of photographs taken in the 1970s in order to explore with Travellers the dramatic changes that had taken place in their lives. The following account, however, is of our first fieldwork, when Irish Travellers were still nomadic and many were moving to urban areas for the first time.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF NOMADISM

Despite their outward similarities to Gypsy groups, Travellers are native to Ireland and one of several indigenous nomadic groups in Europe.1 They have traveled Ireland’s roads for centuries, at first on foot, then in horse-drawn carts and wagons, and still later in trucks and trailers. Their nomadism, in contrast to the movements of hunter-gatherers and pastoralists, is based not on animal migrations and seasonality but on the sedentary population’s need for certain services and products. Consequently, they and similar groups are sometimes classified as “service” or “commercial nomads.” In the recent past, Irish Travellers were primarily tinsmiths, chimney sweeps, peddlers, horse dealers, and agricultural labors. By the late 1950s, as these rural-based occupations became increasingly obsolete, they began migrating into urban areas in search of new ways to make a living.2 Most women initially walked from door to door in the suburbs, asking for handouts, in an adaptation of rural peddling, while men and boys scoured the city for scrap metal and other recyclables. Both of these activities—as well as Travellers’ “illegal” and unsightly camps and urban householders’ concerns about safety, property values, and other issues—resulted in a public outcry. No longer part of the fabric of Irish life as they had been in the countryside, Travellers were increasingly viewed as social parasites living “off the backs” of the settled community.

SERENDIPITY AND FIRST FIELDWORK

We first became aware of Travellers, or “tinkers” as many Irish in the 1970s called them, while still in graduate school. In 1970, I participated in a summer anthropology field school in Ireland and lived in a small fishing and farming community in county Kerry. On the drive there, I saw Travellers camped on the roadside and wondered who they were, but it was George who had the first opportunity to get to know them. While waiting in Dublin for my program to end, he found work collecting demographic information for a biological anthropologist studying Traveller genetics. He met several families then and took their photographs, sending copies back to them that fall. Little did we know how significant this would later prove.

Both intrigued by Travellers, we purchased a copy of The Report of the Commission on Itinerancy (1963) before leaving the country. It laid out the findings of the government commission that had been charged with investigating the “itinerant problem.” The report documented not only the problems that the influx of Travellers was creating in urban areas but also the harsh conditions most families lived under—their poverty, illiteracy, lack of the most basic amenities, poor health, and shortened life spans. It recommended the construction of official “sites” where families could legally park their wagons and trailers and have electricity, water, toilets, and better access to health care and schools. Although the report paid some attention to preserving Travellers’ nomadic life, the ultimate goal was clearly integration; the logo of what soon developed into a national Itinerant Settlement Movement was a curving road leading to a house.

Back in graduate school that fall, George showed Charles Erasmus, a faculty member and his advisor at UCSB, some of his Traveller photographs. Erasmus was intrigued and surprised to learn that no cultural anthropologist had ever studied them.3 Soon, he was urging us both to abandon our plans of going to Mexico for our doctoral research and to seek funding for Ireland instead. His enthusiasm was infectious. The dream of most anthropologists at the time, although rarely achievable, was to find a culture that had not been studied.

We immersed ourselves in the social-science literature—conducting what is commonly called a “lit review”—on Ireland and on similar nomadic groups in other parts of the world in order to begin formulating our research “problems.” I decided to explore how Travellers, who are so fundamentally like other Irish people in that they are English-speaking, Roman Catholic, and indigenous to the country, had maintained a separate identity for generations. George wanted to examine their city-ward migration and adaptation to urban life. Convinced that these were the most significant issues to study and with modest research grants to support us, we returned to Ireland the following summer to begin our doctoral fieldwork. Dublin, with the largest and a rapidly growing population of Travellers, seemed the best place to go.

Figure 2-1. Sharon and George Gmelch in Santa Barbara, California, just before leaving for fieldwork, 1971.

Our Aer Lingus flight landed on July 19, and our fieldwork began the same day during the cab ride into the city when George asked the driver about Travellers. “The government is trying to house them,” he told us, “but they don’t want to be locked up.” In what later proved to be a common stereotype, he added, “One family got a house, but they let the horses inside and cut the banisters up for firewood.” He claimed to have seen the horse looking out their second-story window.

After checking into a bed-and-breakfast and catching a few hours’ sleep, we made a list of things we needed to do: rent a flat, buy a used car, obtain a year’s visa, and contact local officials about our research. Eager to get under way, George phoned Eithne Russell, a social worker he’d met the previous summer. She invited us to attend a Traveller wedding the next day, assuring us that the family wouldn’t mind. She thought they’d be delighted to have some Americans there. As it turned out, George had met members of the family the previous summer and had sent them photographs, so we were welcome.

The ceremony to sanctify the “match” or arranged marriage of Jim Connors and Mags Maughan took place at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Churchtown, a Dublin suburb. We arrived expecting a large gregarious crowd, but only a couple dozen people were there, and an air of detachment seemed to pervade the gathering. Most of the men stood outside the church, while the bride’s father and female relatives waited uncomfortably on the pews inside. When the fifteen-year-old bride finally appeared, she seemed shy and looked somewhat woebegone in her wrinkled wedding dress. The groom’s expression was difficult to decipher. When the priest took them by their elbows and jockeyed them into position in front of the altar, instructing them on what to say and when to say it in what seemed to be an unnecessarily loud and impatient tone, I couldn’t help but feel embarrassed on their behalf. A handful of neighborhood children drifted in during the ceremony and stood at the back, gawking at the spectacle before them. Then suddenly, it was over, the customary Mass omitted. As the newlyweds emerged from the church, a young garda (police officer) leaned out his patrol-car window and called Jim over, advising him to “start out right” and be “well-behaved.” As Eithne explained later, petty larceny was becoming a growing problem among Travellers in the city, and Jim was out of jail on bail for the ceremony.

IDENTIFYING A COMMUNITY AND SETTLING IN

Within the week we had purchased a used VW Beetle, leased a small “bedsitter” (studio apartment), and begun visiting Traveller camps around the city. One of the first issues we faced as fledgling anthropologists was delineating the boundaries of the population we hoped to study. As graduate students participating in rural field schools, we had each lived in a small village. Dublin, in contrast, was a large city with 1,500 Travellers scattered around in at least 50 camps. Some were roadside encampments of two or three families; others were groupings of up to a dozen families who squatted on undeveloped land or amid the rubble of derelict building sites in the city center. The government had also established three official Traveller sites for up to forty families. As lone researchers planning to do in-depth participant-observation research, we needed to identify a community where we could live with Travellers.

Figure 2-2. A typical unauthorized Traveller camp in Finglas, county Dublin.

Participant observation is a research technique in which the anthropologist learns about the life and culture of a group by living with it for an extended time—usually a year or more—and sharing in its activities on a daily basis. The goal is to develop as complete an understanding of people’s lives as possible, including the behind-the-scenes behavior that survey research or a visiting interviewer seldom catches. Learning about a culture in this way also generates insights and questions that a researcher might not otherwise formulate, and it provides many opportunities to check ideas and interpretations with the people under study. Since an important goal of anthropology is to grasp the emic, or insider’s point of view, what better way to achieve it than to live alongside people and participate in their daily lives. A drawback of participant observation as a research strategy, however, is that it cannot be replicated by another researcher nor its conclusions easily evaluated for reliability. And sometimes dangerous conditions may put the resident researcher at risk. We dealt with discomfort and occasional fear while living with Travellers, but seldom more.

After visiting most of the camps around Dublin, we began concentrating on two official sites. Both had large, somewhat stable populations who were not subject to eviction as were Travellers camped on the roadside or squatting in vacant fields. Labre Park, located in Ballyfermot on the west side of the city, was Ireland’s first Traveller site and had space for thirty-nine families who lived in small one-room dwellings called tigins (Irish for “little house”), with extra family members occupying wagons and trailers parked nearby. Holylands was an undeveloped site in Churchtown on the opposite side of the city. Here, families parked their wagons and trailers on two wide strips of asphalt separated by a central, grassy field. A single water tap and a rarely used outhouse were the only amenities for about twenty families.

FINDING A ROLE AND DEVELOPING RAPPORT

Arriving in a camp, we’d park our battered VW and walk off in separate directions to approach individuals or groups of Travellers, hoping to engage them in conversation. Our first impressions were not flattering and were undoubtedly colored by our own insecurities. The men looked tough and intimidating with weather-beaten faces, tobacco-stained fingers, and an evasive manner. The women, although less forbidding because many were pregnant and somewhat matronly in appearance, also seemed distant. Fieldwork among Travellers, we feared, might be more difficult than we had anticipated.

Travellers’ initial reactions to us varied. On early visits we were usually surrounded by children clamoring for a handout—“Aah, miss, could you give us a few coppers?”—as they did with most buffers (non-Travellers) they met. We never gave since doing so would have cast us in a role that was incompatible with fieldwork and the friendships we hoped to create. No matter which camp or official site we visited during those first weeks, the men remained aloof. Sometimes George would approach a group standing around a campfire only to have it disintegrate as, one by one, the men drifted away until eventually he was alone. It was difficult not to take such rebuffs personally. I had more luck with the women, but even they were not always friendly. Some people were curious about us; others, suspicious.

A common problem in doing field research in many places is that the anthropologist doesn’t fit into any familiar outsider category. To the Travellers, we were neither social workers, settlement committee volunteers, government officials, clergy, or police. On top of that, we were Americans. We later learned that some Travellers initially suspected that we were undercover agents. Our first visit to Holylands had taken place just one week after a suspicious death: a man had been found hanging from a tree the morning after a drunken argument with his wife. She, we were later told, had raised her skirt over her head, exposing herself to others at a campfire and thereby deeply shaming him. The police concluded that the death was suicide, perhaps accidental, but some in the camp believed it might have been a murder and initially thought that we had been sent to investigate.

The early stages of fieldwork, whatever the setting, are often challenging and stressful. Untutored in the culture and the nuances of language, beginning fieldworkers are unsure of what behavior is appropriate and, consequently, are forced to learn largely by trial and error. Moreover, they are dependent on the cooperation of people they hardly know. During the early weeks, I always felt on guard, constantly monitoring my behavior: wanting to be friendly but not too friendly, wanting to show interest but not be overly curious or intrusive. We both ate whatever food was offered us, casually negotiated our way around the scrap-metal piles and animal excreta that littered the site, and strived to act composed no matter what happened, which included sitting on mattresses saturated with baby urine on a couple occasions.

Early on, Travellers repeatedly asked me the same questions, even during the course of a single conversation: “Are you married? How long have you been married? Is he your husband? Do you have any children? Don’t you like children? Are you from America? Have you seen cowboys? Do you know Elvis?” Travellers were genuinely curious about these things, but we also had few shared experiences on which to base more wide-ranging conversations. I also interpreted their questions as a test of our truthfulness. That is, were our answers consistent? Some days, the thought of seeking out people to talk to, risking rejection, and answering the same questions over and over was almost too much to bear.

At first, most of our conversations were with children, teenagers, and the elderly. We tried to clarify our role as American anthropology students who wanted to learn what it was like to be a Traveller. We explained about writing doctoral dissertations, which they interpreted to mean books. When they asked how long we were going to stay and we answered, “A year,” they were skeptical. Most contacts Travellers had with outsiders were short-lived—a brief economic transaction, questioning by the police, and the like. After repeated visits, however, people began to realize that we might be serious. As we became more familiar, they became friendlier. We were gradually building rapport—that necessary sympathetic relationship and understanding between a researcher and the people he or she lives among. Not being Irish may have worked to our advantage. Besides the novelty of our being Americans, it probably lessened their suspicions that we were something other than what we claimed.

After several weeks of commuting between Dublin camps, we chose Holylands as our primary research site.4 Its layout was better for fieldwork than that of Labre Park since the families were camped in wagons and trailers facing one another across a central field rather than being strung out single file in crowded tigins. This made daily life readily observable. Holylands also contained a better cross section of the Travelling community. Some families hailed from the more prosperous East and Midlands, while others came from the poorer west of Ireland. Some had been living in Dublin for nearly a decade, while others were recent arrivals and still quite mobile. Besides a stable core of families who remained on the site the entire thirteen months of our research, another dozen or so families came and went.

Although we had met most of the families living at Holylands by the end of the first month and felt quite comfortable with them, commuting to camp each day from our rented bedsitter was unsatisfactory. Travellers often made plans on the spur of the moment. Some days we would arrive in camp to find that virtually everyone was gone. George’s attempts to accompany various men on scrap-collecting or horse-buying trips were no more successful. He might arrive at the site first thing in the morning and then wait hours, never certain they wouldn’t decide to skip the activity altogether. Few Travellers could tell time or had any need to, and understandably, our “appointments” were far more important to us than to them.

Increasingly, we realized that we were missing out on important events. This was reinforced each time we arrived in camp to be told something like “You should have been here last night, the guards [police] came up and took Big John.” More importantly, we wanted to lose our outsider status and get “backstage,” to borrow sociologist Erving Goffman’s metaphor, to blend into the background of camp life so that people would feel comfortable and act naturally around us. Travellers were used to dealing with non-Travellers in superficial and manipulative ways. It was important for us to view their lives from the inside, to observe everyday behavior, and to try to learn what they really thought and, as much as possible, to see the world as they saw it. Moreover, because Travellers had never been studied in-depth before, we felt a need to collect as wide a range of ethnographic data as possible. Only living in a camp would enable us to do this.

Early in the second month of our fieldwork, several people in Holylands suggested that we buy a wagon and move onto the site. It was foolish to pay rent, they said, when we could live at Holylands for free. One day Red Mick Connors and Mick Donoghue took George around to other camps in the city to find a barrel-top wagon to buy, and within a week they purchased one for £100 (US$250). It was in need of paint and a few repairs, but this gave us something tangible to do each day when we arrived in camp. And now that it was clear that we really intended to move in, the social distance between ourselves and Travellers lessened.

As we worked on the wagon, people stopped by to give advice, lend a hand, or simply chat. Some days we arrived to find that someone had worked on our wagon in our absence. Michael Donoghue painted its undercarriage a bright canary yellow—its proper color. His father, Mick, made a new window frame for its front Dutch-style door. Paddy Maughan found replacement shafts and later helped George bargain for a horse, a large black mare named Franny. When our fieldwork was over, we sold her to Paddy at the same price (US$350), not realizing she was in foal and, therefore, worth considerably more. (When we returned to Ireland in 2011, several Travellers confessed that they had known this at the time but that they had been warned by their parents not to tell us since that would interfere in another Traveller’s business.) I made curtains for the wagon’s windows and laid red linoleum tiles on its tiny floor. Nanny Nevin gave me a lucky horseshoe to nail above the door. Once the repairs were complete, we bought camping gear—sleeping bags, a lantern, pots and pans, dishware, wash basins, and a small camp stove—and moved in.

Our transition from regular visitors to camp members was completed the first night when we were awakened around midnight by the roar of trucks and vans racing into camp, followed by loud talking and laughter as people returned home from the pubs. Not long after the camp had settled back down to sleep, a loud argument broke out in the trailer next to us. Accusations and obscenities were hurled back and forth, followed by screams, thuds, and shattering glass. I crept out of bed and cautiously peered through the wagon’s small front window, catching an oblique glimpse of my new neighbor as she staggered out her trailer door. It was the first time either of us had ever heard, let alone witnessed, domestic violence. It would happen several more times during the year, raising an ethical dilemma, although there was no real way for me to intervene except to hide my neighbor when she fled. Only a close male relative like a brother or son would intervene on a woman’s behalf.

The next morning we acted as if nothing had happened. Everyone we saw, however, seemed subdued and somewhat sheepish. As Nanny Nevin walked by our wagon, she coyly asked me how well we’d slept but made no direct reference to the fight. Sam, the eight-year-old son of the family involved, came closest when he said, “You must have learned a lot last night.” Indeed we had. Many of the polite public fictions maintained for visiting outsiders had been broken. We soon realized that Thursdays, the day that the men received the “dole,” or unemployment payment, were days of heavy drinking for many that, not infrequently, ended up in arguments and, sometimes, domestic violence once they returned home.

Living on the site dramatically improved our rapport. We could now talk to people casually while going about our daily chores of hauling water, preparing meals, or searching for our mare. We no longer had to force conversations as the visitor must but could wait for opportunities to talk to arise naturally. People quickly became accustomed to us and comfortable with our presence. We had gotten backstage and were beginning to know and share the private lives of Travellers.

Our research and lives soon fell into an enjoyable routine. Because Travellers spent much of their time out of doors, they were more accessible than the people who had been in the villages in the west of Ireland and Mexico where we previously had done student fieldwork. Every family lit a campfire in the morning and kept it going until they went to bed at night. A blackened kettle of water was kept hot, and pots of tea were brewed throughout the day. Much of our fieldwork involved talking to people while sitting around a campfire. At night, most men and some younger couples went off to the pubs to drink. For several weeks we wanted to join them, since we imagined that it would be a good opportunity to talk, but didn’t feel confident enough to ask. Then one evening we were invited along by some of the Connors men and learned that they had been talking about doing so for a while but hadn’t been sure that we would want to be seen with them in public or go to the few working-class pubs that served Travellers. After that, we joined them most evenings, often sitting around the campfire afterward to talk and drink some more.

Figure 2-3. The late-morning routine at Holylands as people mobilize for work. The men on the cart are leaving to collect scrap metal in Dublin.

Sports provided another outlet for socializing. The boys and younger men in camp often played handball or a version of cricket using a tennis ball and a board as a bat. George had discovered the value of sports in building rapport and creating friendships while living in Mexico after he joined a village basketball team. With this experience in mind, and seeking a way to get more exercise, he suggested to several men that they form a soccer team. No one at Holylands had played on an organized team before, but the idea quickly spread, and soon a team was formed and christened the “Wagon Wheels.” During the week the teenagers and younger men practiced in a nearby field, often having to clear it first of their horses, which they illegally grazed there. On weekends they drove to different venues around the city to compete. Their matches—all against teams comprised of non-Travellers—were eagerly anticipated and underwent endless analysis afterward. George’s role in organizing the team and his play as goalie further cemented our place in camp. When we returned in 2011, there was much reminiscing about the wonderful times spent playing soccer and beating the buffers (settled people) during the Wagon Wheels’ first and only season. Even adults and children born long after our initial departure from Ireland knew about the team, although they mistakenly believed that it had been unbeaten the entire season—a lesson in how unreliable memory can be or how important embellishment is to good storytelling.

PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION AND FIELD NOTES

Most of our data were collected through participant observation, that is, by observing and participating in the everyday life of the camp and then writing up detailed field notes. Participation, however, is always a matter of degree. We didn’t, for example, regularly accompany Travellers on their daily economic rounds. Our time was usually better spent by staying in camp where we could have extended conversations with people, observe the ebb and flow of camp life, and be around when unexpected events occurred. We also used the hours when most adults were away on their economic rounds to pursue other aspects of our research, such as visiting archives and government offices, interviewing settled people who worked with Travellers, or typing up our field notes.

Still, it was important to directly experience what men and women did when they left camp each day to earn a living and to observe the kinds of interactions they had with settled people. On a few occasions I accompanied women “gegging [begging] the houses,” and George joined the men on their scavenging and scrap-metal-collecting rounds, although they made it clear to him that a “scholar” like himself, by which they meant an educated person, should not knock on any doors. Being with Travellers on such occasions produced insights. While out with Mick Donoghue on his scrap-collecting and knife-sharpening rounds, for example, we encountered the disrespect Travellers often faced. As we drove through a middle-class neighborhood in Mick’s horse-drawn cart, several youths ran after us, yelling, “Knacker,” and tried to jump onto the back of the cart.5 A horse-buying trip to the Midlands with Bun Connors was memorable largely for what it revealed about illiteracy. Bun followed a long and convoluted route in his lorry, passing up several road signs that clearly indicated a more direct way.

We also hitched our mare, Franny, to our barrel-top wagon and journeyed into the Wicklow countryside for several days with the help of teenagers Anthony Maughan and Michael Donoghue in order to learn firsthand what traveling entailed. Our first afternoon, we experienced some of the discrimination Travellers faced when, soon after making camp, a farmer cycled by and not long after a patrol car arrived: the farmer had accused us of chopping up his fence posts for firewood and breaking a window in one of his outbuildings.

Much of our data were gathered through conversations or informal interviews. Every morning we each jotted down the topics or questions we hoped to explore during the day, steering conversations toward them. In the process we learned what topics were sensitive, when (and when not) to ask direct questions, and which subjects were acceptable to broach in front of whom. It isn’t always easy to know which topics are neutral since what is considered harmless in one culture may be sensitive in another. So we started with the general. Early weeks at Holylands were spent learning about the logistics of traveling, the skills of tinsmithing and rural peddling, and the characteristics of settled people in different parts of the country. As time passed, we left the historical and general behind and raised contemporary and potentially sensitive issues—welfare, discrimination in the city, drinking, family problems, and trouble with the law.

Figure 2-4. Taking a lunch break on the road in county Wicklow, with Anthony Maughan and Michael Donoghue.

We each kept separate field notes and regularly reviewed them to see what information was thin or missing and to formulate new questions. We jotted these questions down on paper, which we carried with us to consult during the day. When we had heard the same answers often enough to be confident of the accuracy of the information, we moved on to new topics. We seldom took notes openly. Since most Travellers were illiterate at the time and could not have known what we were writing, we felt that it would be insensitive to do so. Instead, we each returned to our wagon during the day to write down a few key words and details from which we could later type up complete field notes. These “jotted notes” were usually enough to recall an entire conversation or event.

Only when the information we were being told was detailed or a conversation had evolved into an interview did we openly take notes. Examples included family histories when many names and places were mentioned or when someone was attempting to teach us Gammon (also known as “Cant” or “Shelta”), the Travellers’ secret argot. We rarely used a tape recorder as it usually attracted a crowd of children and young adults who wanted to sing into it. In retrospect, we probably could have taken notes more openly after the first couple months. Doing so would have let people know when we wanted to have a serious conversation and signaled that we felt what they had to say was important enough to record.

The importance of keeping good field notes had been drilled into us in graduate school and the field schools we had each attended. Not only do your notes form the bulk of your data, they are also a nice measure of what you have accomplished. Well disciplined, we tried to set aside time every day for typing our notes. In this pre-computer era and lacking thumb drives or cloud storage, we each made carbon copies and mailed them home. We stored our originals away from Holylands, along with the electric typewriter we typed them up with, to prevent any possibility of their being taken or lost. Our joint efforts over the thirteen months of fieldwork produced nearly three thousand typed pages of notes. Proud of this “evidence” of our diligence, the first thing we did upon returning to California was to build two wooden file boxes to hold them.

Although we both arrived in Ireland with a clear “problem” to study, anthropologists of our day were less concerned with theory than with ethnography—detailed descriptions of a culture. Furthermore, no one at the time had done extended fieldwork with Travellers, and little was known about their lives. Consequently, we believed we should collect as much data about their culture and history as possible, whether or not we could see a direct connection to either of our specific projects.6 George, for example, collected information on and later wrote an article for a folklore journal about the history of the barrel-top wagon.

Many topics came up spontaneously, initiated by Travellers. Individuals frequently stepped up into our wagon, shut the door, and sat down to talk. Anthropologists as neutral outsiders who have shown great interest in the people they live among often become confidants. Information and feelings that could not be shared with other Travellers because of family rivalries or fear that the information might someday be used against them could be discussed with us. We didn’t need to remind each other never to reveal to other Travellers what we learned in private.

Being a couple proved to be an advantage in the field. Singly, we would not have been able to interact freely with members of the “opposite sex.” Travellers described themselves as “jealous,” and we observed incidents of men arguing and sometimes beating their wives after learning that they had spoken to another man on the site even when the interaction had been totally innocent and other people had been around. Our immediate neighbor, Red Mick Connors, once returned home from the pub and upon learning that his wife Katie had given another man a match so he could light his cigarette, began yelling at her. Katie had been surrounded by her children and had not left the doorway of her trailer to do so, which I had witnessed and intervened to tell Mick. When on my own, I had access to women, children, teenagers, and the elderly of both genders. George’s situation was reversed, although he had to be careful to avoid being alone with teenage girls. As a couple, we could not only share our observations about the opposite gender but join in a greater range of activities such as going to the pub with other couples at night.

Like all anthropologists, we relied heavily upon the friendship and assistance of a few individuals who became our primary teachers, or “key informants” in the jargon of the day. We were mindful of developing friendships and collaborations with members of each of the three major “clans” (the word that Travellers used for their large extended-family groupings) living in camp: the Connors, the Donoghues, and the Maughans. I became particularly close to Nan Donoghue, the woman who had been beaten our first night in camp, and later wrote her life history.7 George was particularly close to Red Mick Connors, and the feeling was mutual. When we returned in 2011, his adult daughter Mim told George that he had been “me daddy’s best friend.” Anthropologists often develop close friendships with people in the field.

ADJUSTING TO FIELDWORK

Fieldwork is a process of adjustment for both the anthropologist and the people he or she studies. We had habits that Travellers then regarded as unusual, if not bizarre. In our early weeks on the site, children gathered around us in the morning to watch us brush our teeth, talking and pointing: “Ah, would you look, Sharon’s scrubbing her teeth.” On our return in 2011, we learned from some of these children, now older adults, that they had begun brushing their own teeth as a result. And we heard other stories of how Travellers had been scrutinizing us at the time we were observing them. They were surprised that I knew how to drive a car and that I wore jeans, something almost no Travelling women did at the time. Reading a book was unusual since all but one of the adults at Holylands were illiterate. When women asked me why we did not have children, I told them about birth-control pills and explained that we wanted to wait. At the time, birth control was unknown among Travellers. The Roman Catholic Church had deemed it a sin, and the state had made it illegal. Today, this is no longer the case, and Traveller family size has dropped as a result. Other women remarked with mild amazement that we never yelled at each other (we undoubtedly did, but never publicly).

Our most difficult adjustment was to the loss of privacy. Travellers found it odd when one of us went for a walk alone. The idea that anyone would want to be on their own struck them as odd, since they did nearly everything in the company of others. Growing up in large families and living in crowded conditions, they were unaccustomed to privacy. Wagon and trailer walls were thin, and there were always people around. Travellers, especially youths and men, routinely entered other families’ dwellings without warning or sat down at another family’s campfire to listen for a while and then leave, sometimes without uttering a word. We could expect visitors at any time. George installed a latch inside our wagon’s Dutch-style front doors as a deterrent, but most people merely opened the top windows and leaned in to talk or else reached down, unhooked the latch, and entered. This loss of privacy was a small price to pay for the acceptance and friendship we received, as well as the information it provided.

Figure 2-5. Ann Maughan prepares dinner for her family; “Big John” is on the far left.

While we made an effort to get to know everyone at Holylands, it was inevitable that we relied upon some individuals and families more than on others. We had little contact with one of the Maughan families, primarily because the adults drank heavily, were often difficult, and created problems for everyone in camp. The eldest son, “Big John,” age twenty-six, was sometimes abusive. At various times he tossed a burning log under our car, threw a rock through our wagon window, and challenged George to a fight. George described one incident in his field notes:

Yesterday as we were driving out of the site, Big John stepped in front of the car. He was drunk and wanted a ride downtown. We reluctantly made room for him. A couple miles down the road, he changed his mind and insisted we take him back to camp. Already irritated and not wanting to appear weak, I told him politely yet firmly that he could either get out of the car now or continue on with us. He refused, so I pulled into a police station which happened to be nearby. As soon as I stopped, he jumped out of the car and we drove off. This morning he came up to the fire where I was sitting with Red Mick, Jim and Mylee. He was drunk again and announced that he had been in jail all night because of me. Waving his fist, he said, “I’m giving you fifteen minutes to pull your wagon out of this camp or I’ll burn you out.” All eyes were on me. I said, “Well, you’ll have to burn me out then.” He mumbled something and staggered off. The men assured me that I’d said the right thing, but I’m not so sure.

Fortunately for our peace of mind, his family left Holylands about a month later.

OTHER SOURCES OF DATA

Camp life soon fell into a comfortable and productive routine, which began most mornings with chatting with our immediate neighbors, the Donoghues, whose campfire we usually sat at while getting breakfast. Many days ended up back at the same campfire, enjoying further conversation with the Donoghues and passersby. In a letter, George described our routine as winter set in:

Dec 5, 1971: The wagon is cold in the morning. I usually stoke up the small wood-burning stove and get back into my sleeping bag until the wagon heats up which considering the small space doesn’t take long. The small bunk across the rear of the wagon is just six feet across so my head and toes touch, but I’ve gotten used to it. The wagon has great atmosphere. It creaks in the wind and you can hear the pitter patter of rain on the canvas roof. Unless the weather is bad, we eat on the wagon steps or at the campfire next door. At first the kids eyeballed my Cheerios as they had never seen boxed cereal before, nor have they eaten grapefruit. We wash up in a plastic dish pan and use the surrounding fields like everyone else for a toilet. There is no rule about which direction men and women go, so you try not to surprise anyone.

By late afternoon the men and women return from their rounds and there is usually good conversation around the fires. After dinner, we sit around the campfire again or else go to the pub or sometimes to a movie with Travellers. The pubs are noisy and smoke filled but the atmosphere and conversation are good. I am often able to get people to talk at length about the topics I’m working on. The pubs close at 11, and we’re back in camp and in bed by midnight.

Wanting to know how representative what we were observing at Holylands was of other Travellers, we continued to periodically visit other Dublin camps. We also regularly attended a weekly meeting of Dublin social workers working with Travellers. This enabled us to check our observations against theirs and learn about what was happening in other parts of the city. Late in our fieldwork, I was invited to fill in for six weeks when a social worker in a nearby neighborhood went on leave, which gave me the opportunity to more directly experience some of the issues that arise between Travellers and settled Irish in the welfare sphere. Together, George and I made short trips to other parts of Ireland to learn about Travellers’ situations outside Dublin. We also spent two weeks in England and Scotland, visiting local officials dealing with Travellers and Gypsies there as well as relatives of one Holylands’ family.

During the year, we got to know many settled people who were active in the Itinerant Settlement Movement, including its leadership, which was valuable to our research, especially mine, which also explored the type of contact and interactions Travellers had with members of the settled community.8 The friendships we developed with several middle-class Dublin families were especially rewarding. The occasional social evening spent in their homes was not only a pleasant change from camp life but almost always yielded new insights and questions for one of us to pursue. They also directed us to teachers, government officials, clerics, physicians, and even scrap-metal dealers working with Travellers, whom we would later interview.

We also spent many hours in the National Library, searching for early historical references to Travellers, and in the library of the Irish Times, going through bulky file folders of newspaper clippings (long before such files were digitized and searchable). These documented clashes with householders and the police over trespassing and efforts by the Itinerant Settlement Movement to settle Travellers. In the archives of the Folklore Department at University College Dublin, we discovered a set of questionnaires about Travellers that had been completed by schoolteachers across Ireland in the early 1950s. These painted a picture of Travellers’ work and nomadism before their city-ward migration and revealed many of the superstitions and folk beliefs that settled people held about them. When either of us felt depressed, anxious, or simply at loose ends, we could go to one of these places and escape into solitary and productive work. When a complete break from fieldwork was needed, Dublin provided cinemas, theater, museums, art galleries, plays, shops, restaurants, and the zoo—a range of diversions unavailable to anthropologists working in rural villages.

FINAL THOUGHTS

On August 15, 1972, thirteen months after our first conversation with the taxi driver on the drive into Dublin from the airport, we left Holylands and Ireland. We had become very close to some families, making our departure emotional on both sides. We promised to return, which we did several times through the 1970s and 1980s and again in 2001 and 2011. Now, looking back nearly fifty years later, we sometimes wonder why they willingly took us in. How many middle-class Irish or American families would put up with two foreigners moving into their neighborhood, watching how they behave, and asking endless questions about their lives? On the other hand, Travellers didn’t lose anything by accepting us, and most Holylanders seemed to enjoy the novelty of our presence and, we think, appreciated our friendship and the genuine interest and respect we had for their lives. When we returned in 2011, we were honored to learn that three children—one George and two Sharons—had been named after us. We were also pleased to discover people’s fond memories of the Wagon Wheels soccer team and the extent to which it and we had become a part of Holylands families’ folklore.