Читать книгу In the Field - Prof. George Gmelch - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Politics and Fieldwork

Nomads in English Cities

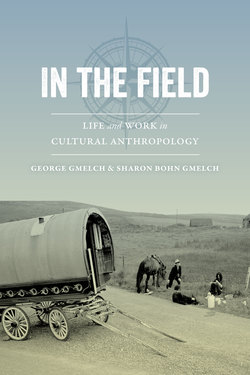

For the first half century of anthropology’s existence in North America, most research was “pure,” that is, conducted for its own sake with little attention given to its practical applications.1 Today, half of American anthropologists are employed full-time by government agencies, NGOs, and the like to help solve specific social problems or provide the cultural context needed to develop new programs or policies. Typical goals include alleviating poverty, improving health, and evaluating the effectiveness of government and nonprofit initiatives. A friend of ours studies behavioral issues associated with isolation and confinement in order to help NASA design better training programs and space stations. Other applied work involves museum curation and historic preservation. Still other anthropologists are hired to help corporations understand how to increase efficiency, improve worker satisfaction, or deliver better services and consumer products.

Others, like us, are employed in academia but occasionally do applied research. We have conducted several research projects for federal and state agencies. Our first—the subject of this chapter—was for Britain’s Department of the Environment (DOE) and the Welsh Home Office.2 It involved studying the mobility patterns of Gypsy and Irish Traveller families living in England and Wales and the problems that the lack of legal places to camp created for them, for nearby residents, and for local government officials. The focus was on the estimated five hundred highly mobile regional and “long distance” families for whom providing legal campsites was most difficult. This chapter explores these issues and the problems of some applied work—in this case, the way politics can intrude upon fieldwork.

NAMES AND TERMINOLOGY

Before proceeding, some clarification of group names is necessary. Although the term “Gypsy” is a pejorative ethnonym (a name applied to group members by outsiders) in some European countries, this is not the case in the United Kingdom. There, it is the term used by many “Gypsy” organizations (for example, the National Gypsy Council) as well as most group members. The term “Traveller” is sometimes used interchangeably with “Gypsy” because of the similarities in the economic adaptation and lifestyle of the two groups.

To further confuse matters, other terms may also be used, such as “Romanichal” and “Romany” (or “Romani”), by those who consider the terms “Gypsy” and “Traveller” to be too broad.In the words of British anthropologist Anthony Howarth, “With the advent of political correctness and Gypsy/Traveller NGOs and Facebook sites, use of all of the terms—Travellers, Gypsies, Pavee, Mincier, Romanichal—has become complicated. However, most Gypsies in the U.K. still refer to themselves as ‘Gypsies’ and they do this with a great deal of pride.”3

Like Gypsies in other countries, those in England and Wales descend from populations who left northern and northwestern India as early as 500 CE.4 The earliest references to them in Britain date to the early sixteenth century, when some arrived presenting themselves as “Egyptians” or Christian pilgrims from “Little Egypt”—understood to have meant the Middle East—from which the English term “Gypsy” evolved. During their many migrations, Gypsies have absorbed language, customs, and marriage partners from surrounding populations. In Britain, generations of contact with householders and indigenous nomadic groups—English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish Travellers—has Anglicized their speech and surnames, although they maintain a distinct identity and customs.

NOMADS IN CITIES

Prior to World War II, Gypsies in the United Kingdom lived in the countryside much of the year. They harvested fruit and vegetables and performed many of the services for the settled community described for Irish Travellers in chapter 2. In winter, when rural work was scarce and travel difficult, many moved into towns and cities. After the war, they began frequenting urban areas on a more permanent basis. By then, many rural trades were becoming obsolete, and campsites were being eliminated as suburbs and highways spread. In 1959, the Highways Act made camping on the roadside or “lay-bys” illegal. At the same time, postwar reconstruction and urban-renewal projects provided new opportunities, particularly in construction and scrap-metal collecting. It was at this time that Irish Travellers began arriving in the United Kingdom in numbers, although there had been some cross-channel (Irish Sea) movement for decades.5 By 1980, when our research began, virtually every British and Welsh city, especially those in the industrialized heart of the country, had Gypsies and Irish Travellers living there.

Although nomadic Gypsies and Travellers formed less than 1 percent of the United Kingdom’s population at the time of our study, they had a high profile.6 Their “illegal” campsites spawned many complaints from local householders and businesses. The evictions that resulted created personal and financial hardships for families and cost local authorities money. In 1968, the government enacted The Caravan Sites Act, requiring all local governments to provide serviced campsites for the Gypsy and Traveller families “residing in or resorting to” their area. By 1980, 166 such “sites” had been built, and another 30 temporary camping places, often just a dirt field, had been made available. Together, these provided space for less than half the population and catered primarily to localized and less nomadic families.

Figure 3-1. An illegal Gypsy encampment next to St. Pancras railway station, London, 1981.

While most householders acknowledged the need for Gypsy sites, few wanted one built near their neighborhood. “If the average householder can even glimpse a Gypsy by standing on top of his wardrobe and looking out the corner of his bedroom window,” a government official in Manchester told us, “he’ll complain.” Residents objected most strongly to the idea of paying to build sites for the “long distance” or highly mobile families we had been asked to focus on, those who lacked local ties and moved into areas unexpectedly. The typical response by local residents was to demand their eviction. When plans to build an official site for them were proposed, residents protested and were supported by their elected representatives. Many legislators believed that the only way to truly end the Gypsy or Traveller “problem” was for them to settle and integrate into society. “Make them settle down for good and live like the rest of us,” declared a Tory councilor. “Why should they be any different?” His views were widely shared. Our goal as anthropologists was to learn what Gypsies needed and wanted as well as the problems local authorities faced, and to provide the DOE with as fair and unbiased an overview of the issues as we could. We were also tasked with making recommendations.

THE RESEARCH PROJECT

George and I arrived in Leicester, a city in the British Midlands, by train on July 7, 1980, after a flight from New York to London the previous day. This was where our research colleague, David Smith, taught and lived. David had been involved in earlier research on Gypsies and Travellers, had proposed the current project in 1978, and had been working with the DOE and Welsh Home Office to lay the groundwork.7 This included obtaining our work permits, which required making the case for why we should be hired as the project’s researchers rather than two U.K. residents. Our prior work with Irish Travellers gave us the necessary credentials.

It was great to be met by David at the train station and immediately be taken to a furnished apartment on Leicester Polytechnic’s lovely Scraptoft campus.8 The project’s office was located in a converted eighteenth-century manor house, on whose estate grounds the campus had been built. It was a large and airy room on the second floor that overlooked formal gardens with a beautifully ornate iron fence and gate. With David’s help we quickly settled in.

During the first week we obtained university library cards and explored the campus—its library, Senior Commons’ room where we could take tea with other faculty twice a day, gym, tennis courts, pottery studio—and tranquil environs. We took the bus into downtown Leicester and were suitably impressed with its timbered Elizabethan buildings and thirteenth-century Guild Hall as well as its clean streets and human scale. We opened a bank account, browsed in a bookstore, and picked up maps at the tourism office. We located a lending library and, observing an entire wall of books in Punjabi, were visually made aware of the city’s multiculturalism.

The next day, David gave us a tour of the surrounding countryside. We were fascinated by his Renaissance breadth of knowledge; he seemed to know everything from the roosting habits of local sparrows to the minutiae of Tudor architecture. Stopping at a quaint village pub for a pint and a Ploughman’s lunch (bread, cheese, and pickle), we spent the entire afternoon talking about the research. We were happy to learn that our schedule as the project’s principal researchers was flexible but disappointed that our planned ethnographic fieldwork had been scaled back. The DOE’s steering committee—comprised of DOE officials, two members of the National Gypsy Council (NGC), and representatives from several local authorities—wanted a survey and were interested only in information that directly related to the central concerns of the project: the migration patterns and accommodation needs of the most nomadic Gypsies and Travellers.

Only statistics, David said, were likely to convince them of the validity of whatever recommendations we might make. We decided to use an interview-based survey with a number of opened-questions as our major research tool and to aim for a sample of one hundred families. While discussing what to ask, it emerged that three generations earlier, David’s ancestors—Smiths and Taylors—had been Gypsy horse dealers who had become grooms and then lost their Gypsy identity. David did not identify as a Gypsy but had many contacts in the Gypsy and Traveller communities based on his work as an educator, local historian, and accomplished wagon and cart painter.

A few days later, we drove to Manchester to meet Huey Smith, a Gypsy leader and head of the NGC, who was on the project’s steering committee.9 The normal two-and-a-half-hour trip to Manchester with David talking the entire way and driving 90 mph couldn’t go quickly enough for us. David warned us to anticipate a confrontation with Huey since Gypsy affairs were highly politicized and given Huey’s personality. Instead, Huey turned out to be very cordial and took us to a department-store cafeteria for lunch where he refrained from asking us a single question about our backgrounds, work, or intentions. Afterward, we returned to his small office which was located on the grounds of a public school.Its walls were covered with maps of England, Scotland, Wales, and London with pins marking Gypsy sites; its floor crowded with stacks of NGC publications. Huey then laid out the history of Gypsy politics and regaled us with stories of the NGC’s battles with other groups he claimed were organized and run by “intellectuals” who used Gypsies as front men. He also revealed the grudges he held against various scholars whom he accused of stealing government money that had been earmarked for Gypsies. Hours later, on the way home, David told us about some Gypsies’ accusations about Huey’s own nefarious financial doings. We listened as attentively as we could, but having to absorb so much new information was exhausting.

Only a week after arriving we were in the car again, this time driving to South Hampton, again at breakneck speed, for a week-long conference on Traveller education. Most of the ninety-five attendees were teachers or government officials, but a few Gypsy representatives were there. It was a great opportunity to make contacts and to learn more about the issues facing Travellers in England and Wales. Listening to talks and discussions about Gypsies for eight to ten hours a day, even though the focus was on education, provided us with a wealth of background information that would otherwise have taken weeks, if not months, to acquire. Most presenters were articulate, if not erudite. But the conference also underscored what a sensitive political issue Gypsies and Travellers were in the United Kingdom and impressed upon us the need to be careful about whom we listened to. We also received a warning from one participant that our findings might not be published or distributed as we might expect. Nevertheless, the more we learned, the more engaged in the project we became.

The conference had its lighter moments too. Most presenters injected humorous anecdotes into their talks, which were greeted with uninhibited laughter from the audience. The personable headmaster of a local school volunteered to drive us to visit a nearby Gypsy site. On the way there, he further contradicted just about every stereotype we held about the reserved and “proper” Brit by revealing his salary, the difficulty he had having sex with his wife while caravanning with friends, and even that his hemorrhoids had forced him to give up sailing.

On the drive back to Leicester, the three of us decided that George and I should spend some time in Ireland, interviewing Travellers about their migration patterns and economic activities in England. We reasoned that since Irish Travellers were the objects of so much animus in the United Kingdom, they might be more forthcoming at “home.” So in mid-August we took the ferry from Holyhead, Wales, to Dun Laoghaire, Ireland—the main route Travellers used to cross the Irish Sea into the United Kingdom. With the help of Mervyn Ennis, a social worker we knew, we were able to interview forty households about their migration to and travel within the United Kingdom. We also talked to social workers, government officials, and ferry and port personnel on both sides of the channel..

We returned to Leicester in mid-September and began making weekly research trips to different parts of the country in search of Gypsy encampments. Unlike most anthropological research, we spent a lot of time on the road, looking for groups of Gypsies and Travellers. It was easy to locate official sites, but our primary interest was in the mobile population. We often learned of an encampment only to arrive there to find that families had moved on or been evicted. Initially, we stayed in hotels, but the smell of cigarette smoke (smoking was then permitted in hotel rooms) soon prompted us to look elsewhere, and we began staying in smoke-free youth hostels instead. Leicester proved to be a good base from which to operate since it is located in the middle of the country. Our goal was to administer our survey in as many parts of England and Wales as possible, also talking informally to families about their travel patterns and evictions, their thoughts about official sites, and related topics. On these trips, we also interviewed the local authorities who dealt with Gypsies and Travellers (for example, county and city planners, government officials, site wardens, and police).

During the course of the year we visited close to one hundred camps, everything from single caravans on the side of the road to large groups, including a sixty-caravan encampment of carpet dealers parked in a field outside Hounslow, a London suburb. Such large groups could be intimidating. As soon as we parked our car, we were usually surrounded by child and teenage “gatekeepers” who aggressively quizzed us on our purpose for being there. We were always greeted by dogs too. The small ones could be real pests, nipping at our ankles as we walked toward the caravans. But as George later wrote in his field notes, “So much in gaining the cooperation of strangers depends on how you approach people and explain your purpose for being there. Finally, we’ve become experienced at this, and our confidence about what we’re doing determines in large measure the kind of reception we get.” Today, this is advice we regularly give students.

Many families turned out to be perfectly willing, if not happy, to talk to us. Some expressed surprise that the “authorities” were actually contacting them in person to seek their opinions. Others expressed frustration, saying they had answered similar questions before. It was often striking how different our experiences of a particular group turned out to be from what we had been told to expect by local authorities. The families we spoke with were almost always more approachable and reasonable. We listened over and over again to stories about the hardship of evictions, the economic losses families endured when forced to leave an area before their work there was done, and the missed doctor’s appointments and family members left behind (sometimes in the hospital). Most families simply wanted to be left alone, to be allowed to stop or camp wherever they liked. But given the realities of modern life and the harassment they experienced from local authorities, the police, and householders, they knew this was not possible. We asked them about the kind of official campsites they might be willing to live on and what amenities and rules were reasonable.

When we met Irish Travellers, we discovered that it meant a lot to them that we had previously lived with Travellers in Ireland. Upon discovering this, they’d usually run through a litany of names until we found mutual acquaintances. I once had the awkward pleasure of speaking with a man who at the end of our conversation pulled out a book and handed it to me, saying, “Now, this person knew what they were on about.” Somewhat embarrassed, but also gratified, I hesitated before admitting that I’d written it.

Much of fieldwork in anthropology is simply listening, a fact of research that is often underappreciated. We realized this when David accompanied us on occasion to visit a local authority. We were frustrated by his propensity to talk, and I found myself mentally pleading, “I know what you know. I want to know what they know!” Interviewing is not the same as a conversation, which David often appeared not to appreciate. Other frustrations also cropped up due to personal and cultural differences. David didn’t take many field notes, got mired in insignificant detail, and struck us both as inefficient. In what seemed to be a British propensity, he would meet with us in the office in order to set up a meeting for the following day to discuss something that could have been dealt with then and there. But he was also knowledgeable and patient and had a dry, ironic sense of humor.

TRAVEL AND EVICTIONS

Which government department a social issue or population is allocated to reveals a lot about how it is perceived. In the United States, American Indian policy was once handled by the War Department. Policy for Gypsies was at the time of our research the purview of the Department of the Environment. Gypsies were apparently categorized as an environmental issue—a moving blight on the landscape—as they roamed the countryside and urban areas, largely uncontrolled, arriving unexpectedly to camp wherever they could, to the alarm of local homeowners and the government officials responsible to them.

Local residents objected to the “unsightliness” of Gypsy camps, the visual clutter of parked trailers and trucks with milk churns, wash basins, domestic paraphernalia, and litter scattered about. Carpet and scrap-metal dealers were the worst offenders because their camps, if they remained long enough, contained heaps of cut carpeting, cannibalized car bodies, and domestic appliances. Tarmacadam (asphalt) layers traveled with trucks and heavy equipment. Other complaints included damage to landscaping and fencing as families tried to gain entrance to land on which to camp. Sometimes buildings and public facilities were vandalized. Just as frequently, house dwellers were disturbed by the noise of the electric generators that some families used, by barking dogs and straying horses, or else were worried about sanitation, theft, or property values.

The typical response was to complain to the authorities and demand that the families be sent packing as soon as possible. Many local councils employed private security firms to enforce eviction orders; others had their own Gypsy eviction task forces. The procedure was costly.10 Knowing this, some Gypsy carpet dealers and tarmac layers intentionally moved and camped in large groups in order to make evictions logistically difficult and more costly and, thereby, gain more time in an area. Local authorities also incurred the expense of cleaning up the site and, in many cases, of trenching the periphery of the land or barricading it with concrete posts, rubble, or fencing to prevent future encroachments.

Evictions were the bane of Gypsies’ existence. Of the 118 families we ended up formally interviewing in 16 English and Welsh counties, 90 had been forced out of their previous campsites. In the previous twelve months, they had moved an average of seventeen times, or about once every three weeks, usually in response to eviction. Many of Britain’s Gypsies and Travellers, therefore, were probably more nomadic in 1980–1981 than they had been at any time in their history. The experience of one of the couples we interviewed is instructive.

Figure 3-2. Police and county council workers enforce a Traveller eviction in Leicester.

After being evicted several times in Birmingham, Percy and Margaret Boswell decided to leave the city and head east. Arriving in Leicester, our home base, they found a place to camp on the outskirts of the city near two other Gypsy families—the Gaskins and the Prices. They spent the first night settling in and talking to their neighbors about work opportunities and mutual friends. The next day, Percy and sons began their search for tarmacking jobs. They found several, and things were going well when ten days later a convoy of police cars and two open-bed trucks carrying city workmen pulled up in the morning.

“All right, lads. Get up!” bellowed one of the policemen, according to Percy. “You have an hour to pull off or we’ll tow you off.” It was early, and the families were still in bed. Striding past their barking dogs, four officers went from trailer to trailer, banging on doors and repeating the message. “Give us time to get our breakfast and feed the children,” Percy had yelled as his baby began to cry. “We have a court order. You’re to be off by eight or we’ll tow you off,” came the answer. The trailers were parked about thirty yards from the highway, shielded from motorists’ view and a nearby factory by a heavy barrier of bushes and shrubs. It had seemed a perfect spot, but once again they were being evicted.

Percy dressed quickly, and while Margaret turned on the gas to make tea and rouse the children, he went outside to confer with the other men; about this time we arrived on the scene. The men debated about whether to cooperate. They were angry enough to force the local council to tow their trailers away but knew they could be mishandled and damaged in the process. Their conversation was mostly a way of passing time, since they had little choice but to leave.

Margaret and the other women went about packing. There seemed to be little urgency in their actions; perhaps they felt there was no reason to treat the authorities with undue consideration. Besides, it took time to feed and dress the children, wash the dishes, fold the bedding, and put loose items securely away. Outside, the older children were loading the trucks with firewood, bags of coal, work tools and tarps, spare truck batteries, assorted scrap, and the milk chums that the families used to store water. The police stood some distance away, watching.

After Percy and the other men hitched their trailers to their trucks, the youngest children piled into the cabs while the teenagers and dogs climbed into the back. Then they slowly pulled out, trailers lurching from side to side over the uneven ground and onto the road. One patrol car pulled in front, and two others brought up the rear, escorting them away. The Boswells had been forced out again. Since the men still had asphalting jobs lined up, they would try to stop as soon as they could. It was expensive to lose a day’s work and to tow a trailer, so they hoped the police would not follow them far. The Gaskins and the Prices knew of a few places nearby, they had told us, a vacant field next to an industrial park, a strip of land by highway construction, a little-used parking lot. As we watched them disappear down the road, the city’s workmen busied themselves digging a deep trench around the perimeter of the land just vacated. No Gypsies would camp there again.

PREJUDICE AND STEREOTYPING

All Gypsies suffer from stereotyping and their failure to conform to the settled community’s romantic image of “Gypsies.” In the early nineteenth century, when England was reeling from the excesses of rapid industrialization and urbanization, their picturesque and seemingly carefree, nomadic lifestyle had inspired the admiration of such authors as George Borrow and Sir Walter Scott. Painters during the Romantic Movement, like Richard Westall, often placed Gypsies and their tents and donkey-drawn carts in their bucolic landscapes. Contemporary Gypsies, who tow their trailers with trucks and often live in the midst of urban decay rather than camp in tents at woods’ edge, were, and still are, often regarded as “imposters” by mainstream society. We were frequently told by householders and some local officials that such families were “drop-outs” or “vagrants,” not “real” Gypsies. As one Camden (London) councilor said when justifying his district’s eviction of several families, “If we had a happy group of rural Gypsies sitting around making clothes pegs, then the committee might have been minded to leave them there.”

Prejudice also stems from the belief that Gypsies and Travellers no longer pull their weight in society. Not recognized for the useful services they perform, such as the recycling of scrap metal, they are seen instead as living off the welfare state, tapping into the full range of benefits available to the poor and honest ratepayers while deliberately shunning regular employment. “There was no Gypsy problem until the Gypsies entered the 20th century,” a local official responsible for carrying out evictions in Birmingham told us.

Years ago, they were camped on land where they wouldn’t be seen. And they were poor, visibly poor. Now they have moved into cities to make a living and there isn’t enough open land for them. And now that some drive flashy Volvos and own flashy caravans, there is little sympathy for them. People resent Gypsies driving better cars than they have.

Gypsies and Travellers have been the objects of public scorn and the repeated targets of government policy for hundreds of years. Nomads always create problems for the state, no matter where they are found. Their lack of permanent residence makes them difficult to count, control, and tax. They also cause resentment, and sometimes envy, if for no other reason than they can succeed outside the formal economy and conventions of settled society. In contrast to most workers, they operate independently and control the terms of their labor. The family remains the primary economic unit, with all capable members contributing to its livelihood.

Their subsistence and identity has long been linked to their mobility and family-based operations, which have allowed them to fill gaps in the market that are uneconomic or too variable for businesses that are large or rooted in one place. When they exhaust the possibilities in a local area (for example, collect all the available scrap metal), they simply move on. They can also switch from one activity to another to take advantage of changing opportunities. Unencumbered by property and income taxes and the overhead of a permanent business establishment, Gypsies and Travellers have managed to live successfully on the margins of settled society for centuries.

THE “SETTLED” AND LOCAL AUTHORITY VIEW

As mentioned, we not only talked to Gypsies and Travellers, we also interviewed local authorities in half the United Kingdom’s counties. They provided us with local statistics, insights on residents’ attitudes toward Gypsies, information on the logistical and legal issues they faced, and, always, biscuits and tea. Most took their task of providing official campsites for Gypsies seriously, but given zoning regulations, businesses’ and taxpayers’ vehement objections, highway safety concerns, funding restrictions, and the like, there was always a limit to the number they could provide and their location. We usually found government officials, who are appointed civil servants, to be much more supportive of Gypsies and their needs than were local councilors who were elected by residents and beholden to their constituents. For them, supporting a Gypsy site could cost reelection.

Every few months, we attended DOE steering-committee meetings in London to report on the progress of our research. Midway through the research, we began to make some preliminary recommendations. At a meeting in January, we were told that we needed to pay closer attention to the “perspectives” of local authorities—in other words, to scale back our recommendations. For example, we had argued the importance of providing individual flush toilets on camping or transit sites, rather than the much less expensive communal and chemical toilets that many local authorities favored. We knew that the latter would not work, as they were inclined to smell, and no family, especially Gypsies, wanted to share a toilet or to clean up after someone else. Gypsies have strong “pollution” beliefs related to personal hygiene and separation. Unlike American camping and living trailers, no Gypsy trailer includes a toilet; they are considered unclean, both literally and symbolically, especially in such close proximity to living and food-preparation spaces.

As a personal experience, our research in England was enormously rich. We spent a year traveling throughout England and Wales and took short research trips to Scotland and Ireland. We interviewed people in nearly one hundred Gypsy camps and also spoke to them at major gathering places like the Appleby and Cambridge Fairs and The Derby at Epsom Downs, where Gypsy and Irish Traveller families camped next to each other, yet separately, on the infield, while the queen sat in the royal box to watch the races. We felt fortunate to meet so many interesting people. Our disappointments related to the restrictions surrounding the research, particularly having to rely so heavily on a narrowly focused survey. To get around this, we included as many open-ended questions as we could, kept detailed field notes, and, later, included lengthy quotes in the final report to enter the Traveller “voice” into the record. It was our first applied research, and we went into it without fully comprehending its highly politicized nature. Political and policy considerations slowed the research down in the beginning, kept its parameters narrow, and eventually sidelined it.

Figure 3-3. Inside a Gypsy “flash” trailer at Appleby Horse Fair, a traditional gathering place for Gypsies and Travellers.

After a year of traveling, hundreds of hours of interviews, and additional months spent analyzing our data and writing a 175-page report, remarkably little happened.11 The report was shelved. We never got an exact accounting of who or why that decision was made. The research had been conceived under a Labour government but hatched under Margaret Thatcher. During her Conservative Party’s rule (1979–1990), Gypsies and Travellers fell to the bottom of the government’s priority list. A civil servant in the DOE did write a brief watered-down “circular,” purporting to be a synopsis of our research, which was sent to all local authorities. It contained little or no mention of many of the things we had recommended, such as providing a national network of transit sites for long-distance Travellers that contained individual family amenities (toilet, electricity, and water), architecturally defined spaces, and trash removal. In effect, it was similar to the Bush administration’s deletions of major sections from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports on climate change in the early 2000s, and the Trump administration’s deletion of the EPA’s climate-change website.12 Our report also underscored the right of Gypsies and Travellers to continue traveling. But it was entirely the wrong political climate for such recommendations and the government expenditures they would require. As Gypsy Margaret Boswell told us after the research, “The Gorgios [non-Gypsies] doesn’t want sites being built. . . . They just want us to disappear.”

EPILOGUE

Government policy toward Gypsies at the national level has swung back and forth, alternatively punitive and somewhat “positive,” depending upon the party in power. In 1994, the Conservative government of John Major released all local authorities from their statutory duty (under the Caravan Sites Act of 1968) to provide serviced campsites for Gypsies and Travellers. Not surprisingly, this resulted in a further shortage of authorized places for families to camp. In response, more families began purchasing land in order to build their own private sites. In late 2015, in an ironic move after years of discouraging nomadism, the Conservatives mandated that in order for Gypsies or Travellers to be legally eligible to apply for planning permission to develop their own private sites, they must first prove to local authorities that they lived “a nomadic lifestyle.”

Public attitudes have not softened either. In 2003, the Guardian newspaper reported the following incident.

Imagine an English village building an effigy of a car, with caricatures of black people in the windows and the number plate “N1GGER,” and burning it in a public ceremony. Then imagine one of Britain’s most socially conscious MPs [member of Parliament] appearing to suggest that black people were partly to blame for the way they had been portrayed.

It is, or so we should hope, unimaginable. But something very much like it happened last week. The good burghers of Firle, in Sussex, built a mock caravan, painted a Gypsy family in the windows, added the number plate “P1KEY” [a derogatory name for Gypsies which derives from the turnpike roads they travelled] and the words “Do As You Likey Driveways Ltd—guaranteed to rip you off”, then metaphorically purged themselves of this community by incinerating it.13

During a discussion of the problems posed by an unauthorized Gypsy camp in 2007, an official with the South Cambridgeshire District asserted that the council would “never get rid of the bastards,” adding, “If I had cancer, I’d strap a big bomb around myself and go in tomorrow.”14 More than thirty-five years after our research, it seems that the more things change, the more they have stayed the same—especially when politics is involved.