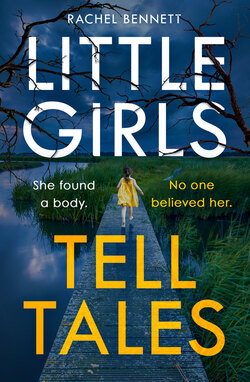

Читать книгу Little Girls Tell Tales - Rachel Bennett - Страница 7

Chapter 1 August 2004

ОглавлениеIf the weather had been better that summer I wouldn’t have found the body in the wetlands. We were only outside that day because, after four solid days of rain, our mum chased me and Dallin out of the house as soon as the clouds broke.

We were allowed to play in the curraghs, the sprawling acres of boggy marshland that began almost on Mum’s back doorstep, so long as we kept to the main paths. Mum had told plenty of stories about how easy it was to get lost, or worse. Some of the boggy ponds were so deep, she said, that if a girl stepped into one it would swallow her forever. I was mostly convinced the stories weren’t real.

My brother Dallin was twelve; two years older than me. He’d spent countless hours playing in the curraghs and reckoned the bog-land held no secrets from him. He never missed an opportunity to lord it over me, this advantage he’d gained by living full-time here with Mum, while I was stuck in Douglas with our dad.

So it was only natural we should follow him without question. Dallin went racing ahead down the main path. His was all legs and arms, like a disjointed puppet. Right behind him was Beth, who’d been in the same class as Dallin since they were at playschool. Her parents had dropped her off at Mum’s house earlier that day. Beth was a quiet soul, as if she’d long ago decided Dallin would be the brash, noisy one. Her brown hair hated being confined to a ponytail and was always escaping in wisps and tufts. Beth and Dallin would never call each other best friends, but only because they never needed to voice such things. When Beth was with us, I felt superfluous.

‘This way!’

Dallin ducked off the main path, vaulted a water-filled ditch, and set off into the trees on the other side, without checking to see if we were following. The trees were spindly and twisted, as if there wasn’t enough substance to the ground to anchor them, and one grew above fifteen feet tall. But that was tall enough. Once we were amongst them, I could no longer see the mountains to the south, my only point of reference on that flat stretch of land.

‘This is more muddy than last week,’ Dallin said over his shoulder. ‘But you’d expect that, right? After all that rain, it’s gonna be like a proper swamp in here, we better not take a single step off the path—’

He chattered away as we walked. Dallin was always talking, always making noise, always restless. Sometimes it was exhilarating to be caught in his slipstream. Other times it was exhausting.

Today I didn’t have much tolerance for him. Maybe it was because we’d been cooped up in the house, or maybe it was the calm press of the trees, but I found I didn’t want to listen. I walked slowly, putting a little distance between us. Beth glanced back once and smiled at me. One of those understanding smiles she was so good at. She was beautiful, I realised in surprise, with golden sunlight caught in wayward strands of her hair. It was the first time I’d noticed.

The path we were following ran along the top of an old dry-stone wall. A hundred years ago, this whole area had been drained for farmland, and these flat-topped walkways had stood waist-high along the boundaries of the fields. But the farmers left, the waters returned, and the trees reclaimed every inch of land. Tree roots climbed up and over the broken stone of the walls to bind them tight. I picked my way over a gnarled surface made of a dozen warring roots.

‘Look, Rosalie,’ Beth said, pointing. ‘Wallaby.’

I hadn’t believed Dallin when he’d told me there were wallabies living wild up here in the north of the island. According to him, they’d escaped from the wildlife park on the other side of the curraghs about fifty years ago, and had been living here ever since. It sounded like one of Dallin’s stories, but Mum had backed him up, for once.

‘They’ve been here longer than any of us,’ she’d said with good-natured annoyance, ‘so I suppose they have the right to go wherever they want. But I could do without them getting into my garden and chewing the bark off my fruit trees.’

It’d been a few years since Mum had snapped our family in two by moving out of our Douglas home and buying the farmhouse up here in the middle of nowhere. The summer holidays, when I was parcelled out to her for up to three weeks, were marked by my sullen silences and unshed tears. At age ten, I blamed her for everything wrong with my life.

Over the last two summers, I’d spotted several wallabies while we were out in the curraghs. They were always at a distance, sitting so still they could be mistaken for broken tree stumps. There was something vaguely sinister, I thought, about the way they watched us. Like sentinels of the swamp.

I followed Beth’s pointing finger and saw the wallaby. It looked bigger than the ones in the wildlife park. Obviously it had spotted us, because it was staring straight at us both, keeping a cool eye on what we were doing.

‘She’s got a joey,’ Beth whispered.

Beth’s eyes were much sharper than mine. I had to squint before I made out the tiny woolly head poking from the mother’s pouch. I wouldn’t have seen it at all except it was restlessly shifting around.

‘Neat,’ I said.

Beth flashed another smile at me.

We kept walking. I glanced back a few times but the mother wallaby was quickly lost to sight. Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling that others were watching us.

The track stepped down off the remains of the wall and wound off through the trees. I kept my eyes on my feet. The path was reassuringly solid, but the ground on either side was muddy and soft. My blue wellies left perfect imprints. On either side of me, standing pools of water gave off a sweet-stagnant smell. The air was heavy and damp with humidity. I looked up. Above the treetops there was nothing but the round bowl of the sky, dotted with clouds. It made me dizzy. Better to concentrate on my feet.

It was maybe five or ten minutes later when I raised my eyes and realised I was alone.

I paused to listen. Dallin would still be talking, I knew. His voice had been a constant drone throughout the summer holidays, half comfort and half annoyance. But now I couldn’t hear him. The only noise was soft birdsong, water dripping from leaves, and the murmur of the wind in the trees.

Dallin and Beth must’ve been somewhere ahead. I’d fallen behind a little, then a little more, until they were out of sight. But soon enough they’d realise I was being slow, and they’d wait for me.

I kept walking.

It didn’t occur to me that I might be lost. The wetlands weren’t that big or sprawling. Probably they were no bigger than the plantation of pine trees near Douglas where me and Dad went out for walks. And I’d never managed to lose myself there. But maybe that was because the plantation was on the slope of a hill. The thousand or so pine trees in their regimented straight lines drew clear pathways back to safety. Even if I got turned around there, I could walk downhill until I found the road.

The curraghs were different. Everything was flat, with no landmarks. There were plenty of paths – dozens of them – but many led in circles or disappeared into bogs.

I walked for some time, thinking – if I was thinking at all – that I was bound to catch up with Beth and Dallin soon. I figured I would come around a clump of trees and there they’d be, waiting for me with a sarcastic remark. But I kept walking and I remained alone.

In the mud off to one side I spotted several elongated, parallel footprints. Wallaby tracks. They led off along an ill-defined trail that headed in what I thought was the direction of the road. I stepped off the path to follow the trail, even though it soon became little more than a line of slightly firmer ground between the stagnant mud puddles.

A few broken chunks of stone protruded from the earth here and there. The remains of a wall, marking the edge of someone’s land? Or maybe part of a sheep-pen, which would lead me round in a loose circle. Perhaps part of someone’s house. There were no clues. Everything had been swallowed by the trees.

At that point I began to feel frightened. Not because I was alone or possibly lost – neither were new experiences for me – but by the evidence of history around me; of time reclaiming the land. A hundred years ago there’d been people living here, but now there was nothing left, except the faint tracery of the walls they’d built. It shocked me to think that time would eventually sweep away the fragments of my own life, the crooked trees tangling over everything that made me unique and memorable.

I had the sudden urge to drop to my knees and dig down through the mud. Buried somewhere must be a few lost remnants of the people who’d gone before.

Later – weeks, months, years later – I would piece the day back together from fragments of memory, looking for signs and augurs I should’ve spotted. There must’ve been something to warn me my life was about to change. Was it significant, the way the wind dropped to an eerie calm, or how the wild geese chattered somewhere off in the distance, or how I spotted those clumps of bogbean – that beautiful, delicate white flower Mum had told me to look out for – growing in sudden abundance in an overwise unremarkable clearing?

It was the flowers that made me pause. The trail I’d been following had petered out to nothing. Ahead, the ground looked boggier, like it might not take my weight. I stopped. The bogbean flowers on their slender stems nodded in the gentle breeze. They poked up between a tangle of sticks in a muddy pond. The sticks were whitish grey, stripped of their bark. I thought of the wallabies that’d chewed Mum’s fruit trees.

I studied the jutting curve of the sticks where they emerged from the water. It took me a surprisingly long time to recognise it as a ribcage.

I’d never seen one in real life, of course. But I’d seen the plastic skeleton at the St John Ambulance headquarters, where my schoolfriend Amanda went to Badgers. I’d spent a long, bored time fiddling with the artificial joints of the skeleton, nicknamed Boney M, while I waited for Amanda to finish training so her mum could give us both a lift home.

What I was confronted with now didn’t look much like Boney M. The ribcage, if that’s what it was, was squashed and malformed, with half the ribs bent at the wrong angle. The bones were discoloured to the same greenish grey as the lichen on the trees. An arm – a possible arm, I told myself – was loosely attached at the shoulder by tatters of greyish material. The hands could be under the water, tucked up beneath the chest. Sleeping. Peaceful.

I brushed aside a few bogbean stems and found what might be the skull. It was partly submerged. Above the water was a smooth curve, part of an eye socket, and the edge of the jaw, complete with a few grimy teeth. The lower jaw had fallen open, or fallen away. One of the molars at the back had a filling in it, grey metal, like the ones my aunt showed when she laughed too loud.

I straightened up, suddenly dizzy. It was a person. I’d found a person.

An unpleasant tingle of surprise worked its way through my stomach. What should I do? In movies, if someone discovered a skeleton, they screamed, or cried, or threw up, or ran away. None of those reactions seemed justified right then, in that sun-dappled clearing, with the birds calling from nearby trees. This wasn’t someone who had died yesterday or the day before or even a week ago. No one was looking for them. And neither was it someone alive and hurt who needed me to run and get help.

This person had been dead a long, long time, perhaps even as long as the farmland had been flooded. Nothing about the scene made me want to scream or cry. There was no blood, no guts, not even a particularly bad smell – or at least, no worse than the rotted-vegetable smell of the mud itself.

Instead of fear or disgust, I felt only sadness. Who was this person? How come they were here? Had they worked in these ancient fields, before the land was reclaimed by trees?

I took a step closer and my boot sank deep into the mud. I jerked back in a hurry. The mud sucked at my boot as I pulled it loose. I stumbled back, breathless.

The first sting of fear hit me then. This was such a lonely place for someone to die. What if the person had been just like me, a little bit lost and a little bit abandoned, and she’d stumbled into the mud and couldn’t get out?

If I got stuck, would anyone hear my shouting? How long would Dallin and Beth search for me? What if I was never found?

I eyed the mud. The divot my boot had made was already filling with scummy water. How deep did the mud go? Could it swallow me whole, as fast as sinking sand? Would I disappear forever, like Mum had warned, held close in a freezing, muddy embrace?

It was that thought that sent me stumbling away, onto a barely-delineated trail that switched back and forth and sometimes vanished altogether. I walked as quickly as I dared. My boots clomped over roots and stones. I almost blundered into another deep pocket of mud, and, after that, I forced myself to go slower. With each step I eyed the ground. Several times I stopped and prodded the mud ahead of me with a stick I’d picked up, to check the ground would definitely take my weight. I took long circular routes around even the smallest ponds.

I had no way to measure time. Later, a great many people would tell me I’d been wandering out there for almost three hours. At the time, the minutes blended together, until it felt like I’d always been walking. My legs ached and my calves were chafed red raw by the top of my wellies.

When I at last stumbled out onto a road – far from where I’d thought I was – I was so numb and exhausted that I kept walking for another half-dozen steps before I noticed I was no longer amongst the trees.

Then a woman I didn’t recognise snatched me up and started shouting, ‘She’s here, Rosalie’s here, we’ve found her,’ like I was an Easter egg that’d been hidden too well, rather than a ten-year-old girl who was so tired she could barely stand.

Someone put a warm jacket around my shoulders. Someone else gave me a packet of biscuits – a whole packet, just put them in my hand and told me to eat, eat as many as I wanted. And then Mum was there, crying and gasping like she’d been drowned, pulling me into a crushing embrace. The biscuits were squashed between us and ended up mostly as crumbs.

‘Where were you?’ Mum asked into my tangled hair. ‘Where did you go, pumpkin?’

I pulled away so I could see her face, and said, ‘I found a dead person.’

The police were already on the scene, having been called by Mum an hour earlier, when Dallin had finally found the courage to go home and tell her he’d mislaid his little sister. I could see the bright police car blocking the road near the car park. There were eight or nine other cars, I realised, clogging the road and parked in the passing places. I would later discover that over two dozen people had turned up to look for me.

‘I found a dead person,’ I said again, because Mum was staring at me like she hadn’t heard. It was important everyone should know.

‘Hush,’ my mum said. She pressed my head back to her shoulder. ‘Hush.’

The police searched the curraghs for the skeleton I’d seen. They kept going until the light faded, and then continued the next day, and the day after. They found nothing.

Three days later, I went back into the curraghs, with a search team of five people, in the hope I could lead them to the clearing with the bogbean growing up through the stripped bones. But, just as I couldn’t find my way out before, now I couldn’t find my way back. Every path looked the same. Nothing was familiar. It was as if the wetlands had shifted and rearranged overnight.

The search team reassured me, but I could see annoyance on their faces.

‘She’s had a nasty scare, being lost,’ one of Mum’s friends said later. ‘It’s enough to play tricks on anyone’s mind.’

‘It’s no surprise she’d make up something like that,’ a few people whispered when they thought I wasn’t listening. ‘She’s always had an overactive imagination, that one.’

‘She did it on purpose,’ only one person said to my face – Dallin. ‘She must’ve heard us shouting for her. We yelled like crazy. She heard us. She just wanted to stay lost.’

I knew other people thought the same. I told my story as many times as I had to, and only stopped when I realised no one believed me. Not my family, not my friends, no one.

‘The police would’ve found something,’ Mum said, at her most diplomatic. ‘They searched everywhere. They took sniffer dogs in to help. I’m sorry, pumpkin, but if there was anything to find, they would’ve found it.’

The only person who supported me was Beth. ‘I’ll help you search again,’ she offered one day at the end of summer, in her soft, sincere voice. ‘We’ll keep looking until we find it.’ And every time we went into the curraghs after that, I knew she was scrutinising the ground as we walked, both of us looking for the bones that haunted me.

In time though, everyone else quietly decided I had, at best, been mistaken. The phantom skeleton in the curraghs was forgotten.