Читать книгу Darling - Rachel Edwards - Страница 11

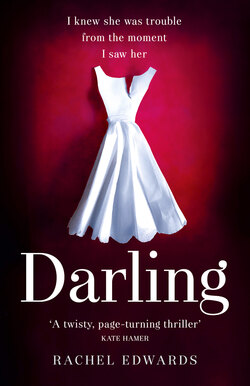

Darling

ОглавлениеSATURDAY, 23 JULY

It was time. My baby had been brought along to meet everybody, but he decided to show the world his tonsils at high volume when I tried to get him out of the car.

‘Come on, Stevie, sweetheart, they want to see you!’

‘No, Mum!’

‘Please, baby, come on, I’ll help you. My little Wonderboy …’

Just like that: the cheekster smile. My son took an inordinate, lips-pulled-wide pride in his name, especially when we played ‘Fingertips’, turned right up. He would not have to sing or perform, ever. But from the moment my future mathematician or philosopher or astronaut had first been flopped on to my chest, I knew he was Stevie (never Steven) Marcus White. My little star, my baby emperor.

‘Please, my love, for Mummy.’

In the distance a train shrieked its passage through the town into the fast-rolling fields.

‘Choo-choo!’ said Stevie.

‘Yes, sweetness, that’s right,’ I said. ‘Now … please?’

With a damp frown up at the strangers, Stevie swung his legs sideways, exactly the way I had shown him, and eased on to my arm, on to his sticks and out of the car.

Once again the door was already open, but this time Thomas stood on the doorstep, a controlled explosion of blonde hair behind his shoulder. She’d washed it and let it dry curly and natural, and I knew there was a reason for that but could not think what it might be. Was she unwinding follicle by follicle or simply trying to make us feel more at home? Both?

‘Hello, Darling! And here’s super-Stevie …’ said Thomas.

This for his daughter’s benefit. Stevie the Wonderboy, I wanted to correct him but I didn’t. Let them get to know him in their own time.

Then I saw her face.

Her father’s shoulder and shadow could not hide her. There it was, the spark of disgust, swiftly snuffed out, when she looked down at my boy. This is why I needed to protect him, right there, in that look.

‘Stevie, Thomas, remember? And this is Lola.’

When I turned the spotlight on her she sprang into action:

‘Ah, OK, would … you … like … to …’

I had to jump in: ‘It’s fine, it’s only in his body. He’s a smart boy, aren’t you, Stevie?’

A squirming, wide-eyed nod.

‘That’s good,’ said Lola, looking at her feet.

Young. She would learn.

Morning unfolded into afternoon with an unhurried Saturday vibe; we were all to hang out together and enjoy the blueberry bran muffins that Lola, Thomas swore, had insisted on baking all by herself in Stevie’s honour.

Stevie winced at the murky sponge and the berries that bit back, but I caught his eye in time; good boy. Lola sat with him for over an hour after lunch and left Thomas and me to chat, mostly about surviving the summer and binning off the school run.

Lola had finished now, but Stevie had another week to go until he got his end-of-year medal. I was so proud of him. Once, home-schooling had appeared to be the only way, but he had been a true lion as ever:

‘I want to play with my friends, Mummy!’

I could not hold him back, I would never do that. So off he went to High Desford’s best primary, no trouble at all. Lola had gone to that nicety-nice girls’ place up the road, of course. Lovely blue uniforms, but – la! – they all wore them so short. My mum would have slapped me upside my head if I’d tried that on.

From the kitchen we could hear them discussing favourite cartoons. That was kind of her, helpful; good to see.

Meanwhile, I twitched. I had vowed not to smoke, in honour of us all. I would end those dashes into the en suite to brush my teeth before kisses, before talking, before breathing; the dashes out of the door to top up on nicotine; the miserable yellow-toothed excuses to the one person who wanted to see me happy. Straight-up cold turkey quitting. No fags, no patches, no nicotine chewing gum, no sugar-free mint chewing gum, nothing but the taste of Thomas. Who needed cigarettes when we had us? Lips were for lovers; from now on I would practise full oral fidelity.

More than the urge to smoke, the blueberry muffins had set off in me a strange urge to bake. It was Stevie’s birthday in a few weeks and I figured I could whip up a dozen or so soppy little chocolate frosted cupcakes with those silver balls.

I am not a natural baker. I like preparing things with skin and bone, skimming fat and salting sauces. But this afternoon something made me want to try. Maybe it was a faint hope that Lola might sniff out a mother figure. We needed a crumb of that sticky stuff. She was embarrassed: we both knew, from as soon as the actual dust settled, that we both knew she had locked me in the cellar. But I was an adult; I had moved on. Just a little kick-out at the nasty ole lady who was kissing her daddy, all pretty textbook. More than that I was a nurse: caring was my life and so was understanding. I got it. And I never planned to try to be ‘Mum’; that would have been wrong, insensitive, futile, crazy. I would simply, as people liked to say, be there for her.

It took me a moment to realise that Stevie had walked in, holding something.

‘Put that down, Stevie! That’s not yours …’

I could not hide the panic in my voice. Dark red-pink and orange in his hands: he had walked in holding a Bright New Britain flyer, snatched up from the hallway. What words – incomprehensible to us both – might he try to read?

‘Come and see our garden, Stevie,’ said Lola, taking the leaflet from him and placing it on the side. ‘Can he …?’

‘He’ll be fine, he can get around with his sticks, just watch him a little.’

‘OK.’

Thomas pulled me to him as we watched them disappear up the garden.

‘We can go and see the pond!’ The small voice drifting over the lavender.

‘Sure,’ said Lola.

The girl didn’t go outside much. A gorgeous garden, but she preferred Facetiming her friends all day. So many friends too; Ellie seemed to be the closest at that time, but it changed from week to week. Girls were strange, these days; I had either had someone for good, or not at all.

I lifted the leaflet from the work surface:

BRITAIN FOR THE BRITISH

We are taking back:

Our borders

Our jobs

Our NHS

Our streets and our kid’s futures … today!

‘What the hell is this?’

‘We never used to get them but they come every few days now. They must be targeting the area …’

‘Oh God, we—’

‘No, sorry, ignore me. We get all sorts of crap through, every day.’

‘And what about my kid’s future? Are we no longer British?’

‘Just ignore it, Darling, please.’

‘I was British, apparently, when I was cleaning up their wasted kids’ fluids and saving their bleeding lives in A&E. Or when I spoon-fed their grandmas. Or when I—’

He pulled me into a hug, into that compelling, hard-won privacy that only parents could know. ‘Time is short,’ he said. ‘Too short,’ I said. ‘I love you,’ he said. ‘Me you,’ I said. The urgency of our kisses became uncomfortable.

Hands on cheeks, hands on shoulders, at my waist, his hands …

‘Dad!’

Lola running up, nearly at the door, no Stevie. No Stevie. Blood? A forever loss, a fall, a drowning – I sprinted, seeing it all already. My boy. I raced past the flowerbeds and bench and vegetable garden, far to the back, by the chestnut tree where the pond hid, dank and gorge deep, skulking away from our eyes. So wide and deep: with those things strapped around his legs he would sink to the bottom. Stevie was nowhere, no Stevie.

‘Darling! What’s wrong?’

A bewildered bass; Thomas running behind me.

‘Stevie,’ my voice snagged. ‘Where’s Stevie?’

Thomas held up his arms, shrugging his whole body. I wanted to punch him in the chest.

‘Stevie! Where?’

‘He’s—’

‘Dad!’

We both spun. Lola was ambling up towards us. I could have flown at her, tugged answers out of that tousled hair. She could see it.

‘He’s fine, Darling, he’s just on the swing.’

‘What?’

‘Look.’

She ran-skipped back up the garden and parted branchlets of willow tree. There was Stevie, sitting immobile on a wooden swing, no longer hidden by the weeping canopy. I ran to him.

‘Push me, Mum!’

It was then that I realised my feet were cold, dirty and bare once again.

‘I was only calling for Dad,’ said Lola, ‘to ask if he would be allowed to swing—’

There, that. Was that triumph in her voice?

‘Of course he can’t fuh—’ I said; Thomas was walking closer. ‘He can’t go on swings, Lola, sorry.’

‘Push me!’

‘No, Stevie!’ The look I gave her was as direct as I could make it. ‘If he breaks a leg he’ll be … it could set him right back. Permanently.’

Thomas took in a rapid breath. Lola lowered her chin.

‘Yes, of course. Sorry. It’s OK, you meant well, Lollapalooza,’ her father said.

‘Of course you did,’ I agreed. ‘No harm done.’

I never wanted him to feel he had to defend her from me. We both knew how well she had meant.

We binned the leaflet and tied up the swing.

Later, Lola disappeared off with a group of friends to something that gloried in the name of ‘Mungojaxx’, a ‘festival for faux-boho future bankers’, as Thomas described it, which drew a tight snort from me. The girl seemed keyed up as she walked out of the door and as she went a certain tension in the breeze whistled right out with her.

The next time we came over, I arrived with two small overnight bags.

Lola had let us in; Thomas hurried into the kitchen ten minutes later, fresh from work.

‘We were just saying yesterday,’ said Thomas, ‘it’ll be lovely to have him stay over. Weren’t we, Lollapalooza?’

‘Were we?’ she asked.

My back to them both, I pressed down on banana flesh with my masher.

‘Come on, Lo …’ he said.

‘What?’ She walked out of the kitchen.

‘Lola!’

‘It’s fine,’ I said, breaking eggs into a bowl. ‘It’s all still so new to her. Go get changed, relax, I’ll bring you something.’

That won his smile back. We were still so new to ourselves that every hackneyed and cosy gesture felt daring, sexy; mixing him a drink in his own home, baking in his Aga. I was now spending so much time at Littleton Lodge that we had decided: time for our first sleepover with Stevie.

‘OK. I’ll just go see to Lola first.’

I nodded and started whupping the eggs, quite hard. After he left I googled on my phone. As I had thought:

Lollapalooza

/ˌlɒləpəˈluːzə/

Noun, North American, informal – A person or object that is more than usually impressive or attractive.

I had heard the word out of that soft mouth a few too many times already. Time after time. I found it irritating, but I needed to stay calm. To relax. Vodka. I would make vodka tonics to ease us into our weekend. First, I scrolled down:

Lollapalooza; also, a gambling term for a made-up hand of cards.

In other words, tricky. I never claimed to be an intellectual, far from it, but I did indeed read into things. Meaning lurked everywhere, even though we could only look back or around us, never see what was to come.

And what was to come?

It had been over a month since the referendum. A lucky seven days since I had last smoked. Things in this country – as with things in my lungs – might have been calming down, or they might not. For a few days after the referendum I had raged. Raged. Then, Thomas had called and I had started to hope we would all just get on with it; rise in the heat, as we always had done. We got on with it. High Desford – not famous, not distinguished, beautiful to few – excelled in that it had become a truly blended town. White English people, Sikhs, Poles, Hindus, Afro-Caribbeans, Chinese, other Europeans and yes, Muslims; genders and sexualities every colour of that proud rainbow; all generations, everyone; even one local character who liked to drape a Partick Thistle scarf across his chilled wares in the market square. Surely, unless you mixed it all up, gave it some heat and bit in brave and hard, you never could know. And maybe a Swedish-born oven, raised in Shropshire, was always destined to bake some bloody lovely Jamaican banana bread.

As it rose in the oven, I went to the drinks fridge. But the bottle of vodka had gone, and the tonic too. I did not stress: that sunshine aroma was already billowing out from the cast-iron conundrum, filling such cracks in our day. Wine would do.

‘Mum?’ Stevie wandered into view. ‘The cartoon finished.’

‘OK, sweetie, I’m coming through.’

‘Can I have some ’nana cake, please?’

‘Not right now, after supper.’

No, the youth was not in charge, today; the grown-ups had already plotted. As our reward, the evening had passed off quietly – Stevie, having seen the size of his new room, lit up the longer silences – and everyone had gone to bed early and eager. None more so than Thomas and I.

Lights left on, always. Our pampered mouths – brushed clear of crumbs and newly minted – were now more than stunned by their discoveries, they were over-sexed and delighted for it. Our bodies were ahead of even our lips. Thomas had seized a no-messing handful of right thigh. With my toes pointing past his shoulder, he eased my thigh higher as we sat, naked, facing each other on the bed; higher he stretched me, back and higher …

‘Mum!’

‘Oh God!’ A hamstring twanged, good as snapped. ‘Stevie darling, hi—’

Thomas had already yanked up the duvet.

‘What are you doing, Mum?’

‘Exercises, poppet. Physio.’ I gave Thomas my first cross look. ‘Door?’

‘It was locked, I swear!’

‘What did you want, baby? You can’t sleep?’

‘I dreamed of Lolly and she came.’

‘What?’ we said.

‘Lolly was here, she told me you wanted me.’

Neither of us spoke for a moment. Then:

‘Of course,’ I said. ‘We always want you, my lovely one.’

Stevie, free of his callipers but broken by bad dreams, clambered on to the bed so he could throw his insubstantial arms around me. I sat back on my haunches, the right one aching like hell, and I pressed my lips to his crown. He wormed into the bed, nestled down under the duvet.

Behind me, a swallowed sigh.

In the morning, Thomas was all smiles and ‘more coffee?’. As the first sure-bring-Stevie sleepover it had not been an unqualified success. Not knowing which child to blame, we yawned, gulped the breakfast blend faster than normal, and blamed neither. But I knew.

I watched as Lola, triumphant, made a show of cutting soldiers for Stevie’s dippy egg.

‘… and this is the soldier that guards the queen!’

She caught my eye; we smiled. Yet my faking lips fell when she said:

‘Next time, Stevie, you’ll have to top-to-toe with me!’

Thomas laughed, grateful. I said:

‘His legs, though, you see …’ and the laughter died.

Maybe I was being too harsh on her, on all of us. Thomas doted on Lola, and Lola might have been coming to dote on Stevie.

I never meant to panic, to make a big deal, to give the impression that he was totally helpless. But that was what thinking about Duchenne muscular dystrophy did to a mum. Thomas understood that; I ought never to forget that he was the man who got me. Thomas understood the sadness in my smiles when Lola petted and teased my boy. I always watched over him, it was my job, my joy. And Thomas understood, deep down, how glad I had to be that his girl wanted to reach out to my baby, even for a moment.

A few days later, we endured a lockjaw-inducing dinner. A meal sucked up through clenched teeth.

Lola needled and carped at everything I said. As I offered her potatoes:

‘You know I’m off carbs, right?’

‘No, I didn’t.’

‘Well, I am.’ A look. ‘I don’t want to get fat.’

And, as a nineties dance tune played on the radio:

‘Tune!’ I cried. ‘I used to love this.’

‘God, it’s really annoying.’

And, as I confirmed to Thomas that I was indeed wearing a new top:

‘Wow, you love shopping, don’t you?’

‘No more than most, I imagine,’ I said.

‘How do you afford it?’ A beat. ‘That top … yes, I think Lizzie HJ’s mum has the same one. You’ve met her, haven’t you, Dad? God, she’s so pretty it’s sickening.’

And, as Thomas reached out to touch my hand:

‘Don’t look, Stevie, old people alert!’

And, as Stevie pulled back one arm and pointed with the other, his favourite Lightning Bolt pose – aimed straight at my loving chest – I said:

‘The Olympics should be pretty incredible. And the Paralympics.’

‘Yeah, but they’re spending all that money on it and clearing out the favelas.’

‘I know, you’re right but—’

‘The games are just so the better countries can show off to—’

Thomas smiled. ‘It’s OK, Lolapoo, relax.’

If she were mine I would have made sure she did more than relax. So much sharpness, such spite; you could catch a nerve on it, trip up and gash your good intentions. Why did he not notice?

Later that night, I was no longer in a receptive mood. I wanted to get the hell away. I wanted a cigarette. But Thomas was ready to share his stories. He wanted to tell me more about what mattered to him. So: Dad George dead, Boise, Idaho, America. George could drink a bottle of vodka for breakfast and defend a rape case before lunchtime. (I popped a mint in, started listening.) This combination of talents gave Thomas the cold sweats to this day. He had died over thirty years before and Thomas still felt weird; cheated that it was a car accident that got him – he had been in a taxi – rather than the burst liver for which his Tommy had spent his whole childhood preparing. His mum, Sal, a Brit, was not much inclined to live in the land of pumpkin pie and prairies. She fled sniffily to England, only to return, in crumpled Chanel, to Idaho, because that was where George was buried. The pull of that car-crash love, beyond pride and maternity and oceans, was such a shock to that practical woman that she never recovered. Thomas still retained some pride in this familiar yet foreign half of him; the US was the sassy, stacked superpower the whole world secretly fancied so he flashed his generous half-Yank teeth as he said:

‘Imagine. Us in Boise, Idaho.’

‘Can’t.’

‘Big fishing country. The Rockies, Pioneer villages … fuck-all, really.’

‘Thomas! I do believe that’s the second time I’ve heard you cuss.’

‘Is that right? Ah, that’s not me, that’s American Thomas. Tom … Wassernacker. He swears like all—’

‘Oh, shut the fuck up and come here …’

‘Darling! I do believe—’

‘Hush now.’

There were bright stabs of joy, daily, despite the teenage parrying. Thomas seemed to be taking to Stevie faster than I had hoped. Going over and above; under and around too, drafting new ways for us all to be. It was a Wednesday evening, and I was to idle in the bath while he took the kids to the summer drive-in, showing Grease. As it happened, the hospital called first, needing me to cover, but his thoughtfulness was no less magnificent.

As Thomas started up the engine, with Lola and my son in his car, my mind buzzed. I wanted Stevie to love culture, even if it started out with some shiny, big-quiffed, ‘Summer Lovin’’; that night he would at least learn something about the beauty of transformation. I read books and watched plays, which some people found surprising, but that in itself surprised me. High Desford was not a complete cultural desert – not compared to Elm Forest, the small, scruffy nearby town where I had spent my early years.

Even if it was semi-arid, I had studied and sought out thoughts, dowsed for words and meaning, drunk it all in ever since we had moved here. If I had not been made a nurse by vocation and were I not Stevie’s destined mother, I would have written. All the blinking time. I certainly read. Some of the first lines I ever committed to memory, apart from Neneh Cherry’s ‘Buffalo Stance’, were from Ophelia’s loco chatting which we had to recite once at school:

‘Lord, we know what we are, but know not what we may be.’

So good. A bit too much sense for real madness, but that seemed to be the point. (We thesps of Class 4C probably did not greatly enhance the meaning with our am-dram gurning and tied-lunatic lurches.)

Thomas and the kids left for the movie before my shift. However, St Foillan’s then called again to explain that they did not need the cover after all, and that the first call had been due to an administrative error, so I opted to hang around alone at Littleton Lodge.

I waited for them, wondering: what must it be to live in a home such as this, with a creator of homes such as this? It would be more than ordinary dreams could offer to see love in every lintel, every stairwell, every last nail. I leaned against the wall of his study; the petrol blue paint still smelled of the cost and challenged the eye in just the right way. He was clever. But more than that he knew how to plan for the way lives would be lived within his spaces, how to build, yes, love into an angle, to create unity and harmony, or division with a layout – a true domestic God. What power! I imagined myself as part of the house itself, a quiet corner or window. I moved upstairs, smoothing the balcony with my hand. I did not know what had been done or how, but interventions had been made in the original building so that the below flowed into the above without a stutter. I pretended to myself that I was doing my old pausing-to-admire schtick, but I knew I was in fact going straight to where I had to be: Lola’s bedroom.

I went in, looking over the made bed, the chair with her stack of ironed clothes that got done by the lady up the road twice a week, the wardrobe and the desk. Tess watched my every move from her frame, the sun lighting up her milk-and-honey mouldings, frozen. I opened the wardrobe door. All the wispy skirts and half-cocked dresses, just smart enough to pour scorn on the mottle-thighed proles, plus a trifle or two of vintage, to my narrowed eyes the whole predictable cache of competitive irony – Behold my sweet regurgitated rara! My jaunty 10p fedora! I, so young and so untender … and so tediously well-off! All of it in colours tied to studied trends, the shapes following sanctioned fashions. Uncharitable, perhaps, but clothes that focused so much on the now and the then did little to move me. Whatever the year, my dress had always had something loud to say about sunshine and breasts and hip-to-waist ratios, even at a younger age, even in the coldest weather; moreover, I had never been so slight. Girl should eat more. I leant into the back of the wardrobe, groped and looked down – nothing but oak and dark space. I withdrew, closed the door and moved to her window, to its unobstructed view over the garden. The best view in the house, really. She was loved. Did she know it?

Finally, I did what I had come to do. I opened her bedside table and sifted. What was inside? Pens, coins, a phone charger, a plastic-sheathed tampon, a couple of hairbands, a notepad, five or six GoGo chocolate bar wrappers, an empty purse maybe. Girl’s mess that did not invite.

Next drawer down: hairdryer, brush, dental floss, that sort of thing. Diet pills (ah!) half empty, more tampons, B vitamins, a few unused soaps, hair oil, foot cream. More debris denoting female effort.

I straightened, looked at the dressing table. Not sure why it caught my eye; perhaps it was the only exposed hint of disorder in that cleaner-controlled room. Peeking out from the third drawer down was the corner of a patterned headscarf. I reached for it, pulled the drawer out. The headscarf billowed up into a silken cloud of ironic paisley. There was a small block of something underneath it. I dug my fingers under, pulled and … yes, Golden Kings cigarettes. We smoked the same brand. If Thomas had the first idea … I planned to have a word, put her straight. A drawer of secrets, then. More scarves – none I could imagine her wearing – and when I pushed through to the bottom, a blue book; an A4 exercise book with a dolphin postcard taped to the cover. The dolphin in its sea was a similar blue-grey so that it seemed as if the creature were swimming out at you from the depths of an ocean which was balanced upon the word HAWAII. Also on the book’s cover, in large neat underlined capitals:

DONE LISTS

There was one entry – DONE LIST 1 – several pages long.

I read it; of course I read it. And then I smiled, dropped my head.

Just a child, I reasoned. A girl alone with her pen and her angry, angry words. I got it, we all needed an outlet. Angry child, angry words. Love would win.

Everything was wrapped, wedged and replaced. Five minutes later the three of them were pulling into the drive. I had texted Thomas about the cancelled shift; Stevie almost skipped to me in his KAFOs.

‘Stevie, careful.’

Lola did not look at me. She would not meet my eye and when I examined Thomas he also seemed to be holding tense words an inch behind the jawline. Our backs to the kids, my expression asked him the question; he responded with the slightest shake of the head.

We readied ourselves for bed. I listened to one message – it was always the same one – then I deleted the seven missed calls, put my phone on vibrate as usual. Enough already.

‘So now, what was that earlier?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The atmosphere.’

‘Nothing.’

‘Really? But—’

‘The kids had bickered a bit, that’s all. Nothing big, everyone’s just tired.’

It did not take a mother to know that his sixteen-year-old girl and my five-year-old boy would get nowhere near arguing, but I said nothing more.

Soon we were locking limbs around each other, never that tired, not then. But even as we stroked our bodies brighter and pushed on through to that grasping, eyes-shut, giving, gasping place where no child could ever find us, I wondered. Lola had changed.

It was as if she could read, in my eyes, what I had read in her room. But of course she could not and, in the end, I did not let it keep me from tumbling into the grave-deep sleep of the satisfied woman.

When I woke, I felt the childish urge to skip the whole breakfast routine and slip us out of the door. But Lola was the teen, and moody by definition. I was not. I swung out of bed, leaving Thomas to snore, went downstairs to my bag to get my phone and – before I had tripped the wire that triggered the brain-alarm ‘Stop, in the name of your flaws’ – I was reaching for the pack of cigarettes, giving it a hopeful shake. I had been almost certain it was empty, but in fact it contained one final stick of tobacco. I ran the cigarette along my upper lip as I breathed it in. I weighed it in my pinch. I rolled it between thumb and finger. I held it between my lips, closed my eyes and waited for the dirty billow of longing to overwhelm me. It did not come. Moved by this lack of feeling – triumphant even – I dropped the packet into the dustbin.

Over breakfast, silence was broken only by exasperation. A wall-faced Lola, with ‘Screw You, Darling’ graffitied all over her. Stevie upturning his bowl in a rage because his KAFO had got wedged between the chair and table:

‘They so annoy me, Mummy!’

Thomas soothed us all but my embarrassment soared as the milk dripped to the floor and then, after a quick wipe around, I gathered my son so we could totter – clack-clack – out of their smart door and drive home.

‘No, she totally hates me, I’m serious. Huh-ates me!’

That weekend I pretended not to listen through the old serving hatch as Lola complained into her mobile for long minutes, muffled by a cushion; you could make out the tear stains on the silk. I sprinkled radishes through the all-Littleton Lodge salad. The lettuce, cukes and curlicues of pea shoots made a fine bed in their bowl. I’d left Thomas and Stevie in the garden, devouring the pièces de resistance: cherry tomatoes plucked straight from the vine.

‘I know, how could she say that to Jess and not have told me?’

I figured she had to be talking to Ellie. I tore up a few more butterhead leaves, picked five minutes before from the Waite patch. Lola went on:

‘Ellie Motte-Ryder is a complete and utter bitch.’

I rummaged for a jug, found one so well designed that it almost annoyed. I glugged some olive oil into vinegar, added mustard, seasoned and whisked. She had not seen me, could not hear me, did not know I was there.

‘I can’t believe she said that!’

It still needed parsley. I slipped out of the back door to the herb garden, snapped a stem or two and crept back in.

‘No … Oh my God, did she? Well just kill me now.’

The herbs in a colander, I turned on the tap, only for the water to explode in a great gush.

‘Hello?’ she called.

‘Only me,’ I said.

‘Got to go,’ she told her phone.

No time to waste. I walked into the sitting room where she was curled up under a throw, limbs unstirred as if under a layer of custard, no matter that the windows were open and it was 78 degrees outside.

‘Can I get you anything, Lola?’

‘No thanks.’

‘Nothing at all?’

Darling White is rude. She’ll get fuck-all of me.

Lola did not speak, stared straight ahead.

‘Nothing?’ I repeated.

‘Perhaps a new life?’ She would not be seen to cry, refused, but her voice caught, a downward glance.

‘Ah, now …’ I moved closer, ready to sit. ‘Why don’t you tell me about it?’

She raised a hand before her face, hiding her eyes, blocking me out.

‘Actually, just a hankie would—’

‘Sure, let me get you one.’

I hurried back to the kitchen; I had to keep trying. I loved to care. Nursing was love – that simple and that complicated – love, time-stamped and dished out to strangers. Caring for your sick child could be similar but it did not vary with precisely the same frictions and erosions and unwanted quickenings and surprise softenings, with the rough incidents that abraded you when tending the wounds of the unknown many. Your love for your child was relentless, and joyous, and painful. But all of it – nursing, caring, loving – there was nothing better, nothing else I ought to be doing with my life.

Grabbing my handbag, I pulled hard at a corner of cotton and there, once again, was a packet of cigarettes that I did not remember buying, was sure I had not bought. The box was light. I shook it, flipped it open and there, once a-bloody-gain, lay a lonely smoke.

Ah, got it now, Lola. Her Golden Kings, all of them, were for me.

I snatched up the hankie, pinched the cigarette between my fingers, held it high and walked back into the sitting room.

‘Why are you giving me these when I’m trying to give up?’

She said nothing.

‘Why, Lola?’

She shifted so that her feet tucked further up under the creamy blanket and lowered her gaze to the floor.

‘You seemed really stressy without them. Just trying to help.’

‘That’s the only reason?’

She looked me in the eye. Looked away.

‘OK … Well, thanks for the support, or whatever, but I need to kick these things. I will quit, too. Here.’ I passed her the hankie.

‘Thanks.’

‘And don’t you even think of trying it.’

‘No way,’ she advert-flicked her hair to one side, patted an eye. ‘That’s never going to happen. I’m not stupid.’

‘Well, that’s fine but—’

Clack-clack. Stevie was coming in, with Thomas close behind.

‘Mummy, we’ve got tomatoes for the salad, look!’

‘Thanks, sweetness.’ I got up, trying to give Lola an ‘our secret’ look. She was staring at her nails.

‘Let me show you, Mummy. Let me show you the plants, let me—’

‘OK, OK,’ I said, with a sunny nod at Thomas. ‘Someone’s had a lot of fun! I’m coming.’

I turned back to Lola once more, but with a wave of her wrist she had already commanded the TV to amuse her. We three walked up the garden. Quite some garden too; long and wide beyond anything I had ever imagined when I had first walked down this street. A lavender farewell by the kitchen door, alongside pots of herbs: rosemary, purple-afroed chives, thyme, mint, a stately bay tree. We walked on, passing the shed, through lawns fringed with a whole production of blooms, past the willow tree and onwards until there, before we reached that murderous pond, we breathed in the must of tomato plants.

Stevie tugged me closer to what was left of them. ‘Here, Mummy.’

‘They’re beautiful, aren’t they?’

‘I wish we could live here so I can eat them every day.’

I said, ‘I’ll buy you some nice tomatoes, sweetie.’

‘But I want these!’

Thomas was saying nothing. My eyes must have spoken despite me, and the look he gave answered at perfect pitch, did not shout, did not whisper.

‘Can I dig a muddy pool?’

Thomas laughed. ‘Sure, why not? I’ll get a trowel.’

I chose that moment to leave them in the sunlight, Stevie sitting straight-legged on the grass in his dew-smeared KAFOs, with Thomas making a whole mudpit of mess in the place where his good things grew, and all for my boy.

Unwatched, I wandered back towards the house with sassy step, arms swinging free, pausing only to lean into the boundary shrubs and pick a trumpet of buddleia. Black and a flash of crimson fluttering out: a Red Admiral weaving up into the sky, first I’d seen for years.

I moved through the French windows into the cool of the kitchen. Lola’s phone drawl drifted to me, a sharp note in the August air:

‘Yeah, she’s still around. And her son … I know … Yeah, she’s basically a pretty big slut.’

My foot paused mid-step. I was rinsed down by disgust and anger, all washed over by something icier: cold shame. Shame that I had even tried with her, shame that I had failed. I turned and grabbed my handbag from the counter, slipped into the dining room, ducked sideways through the conservatory, out of the side gate. I had to have it.

I ran, a mad tiptoed sprint, halfway up the road. Just a couple more final puffs.

Her conjuror’s trick cigarette glowed as I lit it. Lola knew, she had always known. The fags weren’t some anarchic take on Girl Guide charity. She was a Millennial, she had been told her whole life that the nasty things were multi-talented killers. I inhaled deep.

First the cellar, then this. She clearly wished me a slow death.

Almost impressive. Not too shabby; no sugar-candy Mandy, this one. But dislike could do more damage than tooth-rot. No matter, la! I would sure as hell win her over.

One, one coco full basket.

She would change. We would be just fine in the end, Lola and I. Because that was how it was going to be. Love wins.

On the Monday evening, I engineered an excuse to stay over at Littleton Lodge when Stevie was with Demarcus and Thomas was dining with clients. I needed time alone with Lola. I would cook for us.

Food, though, was turning from my gift into our battleground. Most days Stevie ate anything, but Lola? She was a tricky one. That night I offered her spaghetti, with either bolognese or a tuna and tomato sauce, but she ‘wasn’t feeling’ pasta, so I offered grilled chicken and potatoes, but she wasn’t feeling chicken, or potatoes, so I offered a sea bass fillet, not feeling it, sausages, nah, sirloin steak, nah – she wasn’t feeling any meat at all. By this time I was feeling the need for air, so – back in a minute! – I left her in front of the TV and grabbed my bag, which now held a fresh pack of cigarettes, put there by me alone.

I smoked. Then, with my deliberate failure already stale in my mouth, I hit upon a meat-free inspiration: everyone loved my Caribbean vegetable curry. I aimed for Pattie’s West Indian Food Store a few streets away, bought what was needed and wandered back.

There was no sign of Lola downstairs.

I snatched up a knife and cut out the scowling. There would be no asking, nor pleading; no telling, no pandering now, just dinner on a plate. I needed to calm my blood and get this sauce to bubble; it would taste almost as good from Thomas’s overpriced pot. I diced the onion fast – chuk-chuk-chuk – grated the ginger, then fried them together nice and slow. I whistled as I chunked up the vegetables, inhaled a savoury puff which seared my skin as I poured liquid over. A breather.

I padded to the back door. Time for the flavours to mix themselves up, for it all to meld together and break down a touch. I considered another cigarette but remembered Lola’s gift of suffering and pushed the urge aside, for now. I went back to the hob, added coconut milk, stirred and covered.

Soon come.

After at least twenty minutes, I decided to seek her out upstairs.

Lola was in her room. She was sitting up on the bed, Facetiming some friend, and when she looked up I saw it: that naked, honest hatred that she had not been quick enough to hide. So then, Lola.

I stood, rock steady, in her bedroom doorway until she killed the call.

‘I’m making a Caribbean vegetable curry for you …’

‘I’m not really feeling—’

‘What aren’t you feeling now Lola?’ I said. ‘Curry? Vegetables? Or simply the Caribbean?’

A twitch at her mouth. ‘Well. No. I was just going to say I wasn’t feeling that well.’

‘Oh,’ I said. I waited for the sympathy to come, but it did not.

Two seconds passed. Three.

Then from cool flat nothing the magnesium sparked and flared, and Lola reheated a smile:

‘Hey, want to see my new skirt? Try it on if you like!’

It was a black and turquoise patterned mini, and it was pov-chic and it was witty-tacky and it was small as hell; it would never have fitted over my rounded old black backside, even at her age. She threw it down on to the bed, a polyester gauntlet.

I did not rise, I did not move; I paused, made admiring noises.

‘So yeah,’ she said. ‘Not bad for High Desford.’

‘It’s lovely, Lola,’ I said. ‘Anyway, I’d better check on dinner.’

‘I told you.’ That hot metal stare. ‘I’m not that hungry.’

I met her long gaze, eye for eye. A flexing of time, and of wills.

‘OK then.’

I walked out of the room. Lola got up and followed. I stopped by the stairs; she stopped.

‘What?’ I said.

She moved closer.

A loud purr, gravel. A car. Lola edged me forward along the landing, seeming to hear something that made her cry out:

‘Why? Why do you need to be like that?’

‘Like what?’ I said, literally on the back foot.

‘You act like you hate me the whole time!’

She was shouting now, a full-throated yell.

‘What? You can’t be—’

‘It’s true! No. You talk like you like me, but—’

‘Lola!’

‘You—’

‘Lola—’

‘Hi, Darling!’ called Thomas.

And, poor silly girl, in that one weird second she heard not Darling, but darling, and she rushed to the top of the stairs.

‘Hello?’ called Thomas.

But I was still moving forward and she pushed, pushed at me, then more shouting, screaming, a heart-jerking lurch – she was screaming? – and then my arm flew out somehow, anyhow, but she flailed, flew backwards.

Down she fell, a tripping, twisting, puppet’s dancefall right down to the bottom of the stairs.

I looked at Lola lying there, one arm up in a question mark above her small fair head, one arm down, legs bent. A beautiful catastrophe: her broken swastika of a body.