Читать книгу Darling - Rachel Edwards - Страница 9

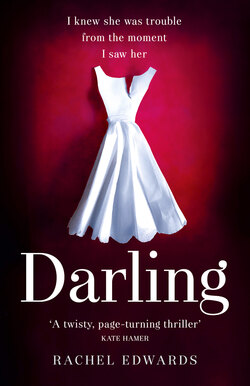

Darling

ОглавлениеFRIDAY, 24 JUNE 2016

I ran. Ribcage, feet and thoughts pounding, I ran and ran and kept on running.

What had we done? Why had we?

Blue, blue, blue, blue, yellow, yellow, a whole buggeration of blue: on and on the results had flashed up, all the live-long night, and now we were out.

Fuck it. Brexit.

Now I needed a fag, I needed my dead mum and I needed a new passport, in that order. The latter two were out of the question, so I had bolted to the supermarket for cigarettes.

When I reached the doors, I eyed myself in the glass. My lips were mud red. I was puffy, my eyes salt-stained and dry; worst of all I was panting in public. Over-exercised, out-voted, thwarted and screwed, but alive and still here, wherever here was now.

On the bright side, nothing made you appreciate a fag like a good sprint.

Two people had arrived before me. There was an old lady wrapped in thick, well-cut mustard – years of knowing that summer mornings could be chilly in this corner of the European Union – tying up her spicy little terrier. And him.

The woman blanked our smiles but he and I met each other’s eye. I was ready:

‘Not long now …’

He was too:

‘Here’s hoping …’ His first words.

A pause; we were taking our time. I could see up close those cuffs that commanded a second look, the sun-starved wrists, the moon rising from each cuticle. The hair, organised, showed more salt than pepper in that still-shocked light. But these were unimportant details. All I could feel was the pressure, building in the nothing between us. With pressure like that you just knew that the universe, or the Almighty, or whatever the hell, was getting ready to give one mother of a push.

6.58 a.m. Friday 24 June 2016.

‘I’m here for my daughter,’ he began at last. ‘She’s turning sixteen and wants me to get “a tonne of good stuff”, whatever that might mean …’

‘It’s her party?’

‘Only the sleepover tonight, the main party next week, but I have no—’

‘Oi-oi!’

Just as he was about to tell me what he did not have, we heard it: the unmistakable cadence of trouble. A heap of a man was arriving, belly first; lumping his way down from the high street, prickled scalp tilted high. From where we stood you could see he was a meeting of both triumph and disaster.

‘Out! Out!’

The red face, the glittering glare: joy gone bad. He was coming closer.

‘Enger-lurrnd!’ he sang, as three more prickleheads straggled around the corner behind him. ‘En! Ga! Lund!’

More fat than muscle but still, he was big.

Then he was nearly upon me, blue marble eyes swivelling, ready to bash at this other thing, this other thing, this dark blot on his brand-new swept street, his clean sheet. A black woman wearing rushed make-up and a look of contempt for his playground punch-up politics.

He spoke:

‘We voted Leave, love. Outcha go!’

I gaped, eye-level with the chest of this sweaty fiasco. Tattoos all over his thick neck.

‘I don’t think there’s any call for that.’

A voice as dark as my skin, it flowed with a current to it. It was him. This man beside me, feet fight-distance apart but fists at his sides, a heat in that count-to-ten stare.

All I could think of was the blood spurting on to that pretty suit.

Then the big man inflated his cheeks and chest, became whale-big. Big of body was a thing for him, you could bet on it, but he liked his ideas small and hard.

‘Wotchoo, er fackin’ ’usband?’

‘Yes,’ said the suited man, moving closer to my side.

The eyes swivelled wilder, the disgust too great. A torrent of blood was surely coming – and then the stragglers caught up.

‘Trev!’ They swept him along, shambled away, a colourous bobbling of orange and dark red-pink T-shirts. As they rumbled on, with the man-mound clasped in their loving headlock, one mate rubbed his knuckles into the headstubble, and the smallest man pressed a lager can up to Trev’s lips. The meaty fist punched out, now into only air, into no one.

‘Whoa,’ I said.

‘Indeed,’ he said. The laughter lines, the rivulets of skin that danced at each idea that rose behind the eyes, eyes that shone. Yes, he was appalled to the core and embarrassed, but above all relieved he was not them. To make sure I knew it, he offered his smile; one warm poultice for our wound.

‘That was scary.’ I stopped short of patting my chest. ‘I have never, ever had that said to me. I was born here—’

‘Idiot,’ he said.

‘Big mad angry violent idiot.’

‘So dumb.’

‘As in “referendumb”.’

‘Ha, precisely. Don’t worry, though. He’s just one nutter.’

‘But he’s clearly swallowed at least two others.’

He laughed, shook his head. ‘They feel emboldened, they were always going to. It’ll pass.’

‘Or get worse.’

‘It’ll be fine. We’re all better than that.’

‘Well … Thank you.’

‘Pleasure.’

‘No, seriously.’ It had to be now. ‘How can I ever thank you?’

‘Actually …’ he said.

‘I always buy them and she pretends not to mind, but she does. I’d be so grateful—’

‘I’m not actually going to bake you one, you know!’

We walked on through the aisles and, laughing, stopped.

‘Here we are,’ I said. ‘Look.’

‘Great.’ He reached for the nearest factory sponge.

‘No, listen.’ I surprised myself with that flirty-bossy tone, me trying to take over his senses so soon. Look … listen … ‘You don’t want a big-brand one with loads of E numbers. Think cricket wife. Wonky, homemade.’

‘Oh, but I—’

‘Hang on.’ There I went again. ‘This one, with apricot jam. Ah, organic. Perfect.’

‘Hold your horses,’ he said. ‘It’s a bit … you know.’

‘What?’ I scanned it for flaws.

‘A bit …’ He smiled. ‘Naked.’

‘Forward,’ I said, walking on.

We put the nuddy-cake in his trolley and continued, weighing each step.

‘Look,’ I said, a few steps later. ‘Icing sugar. You—’

‘I ice it myself, slap “Happy Birthday” on it.’

‘You catch on quick.’

‘Insanely good teacher.’

‘Damn right,’ I said.

‘Best home-made money can buy.’

‘Our secret.’

‘Our naked secret.’ He shook his hair out of place. ‘Sorry, way too forward, crass of me …’

‘No problem.’ Then, new in this territory, in this changed world, I dared:

‘We’re married, remember?’

His eyes sparked, looked away:

‘Whatever happened to our honeymoon?’

Cloud to ground flashes, electric potential under the strip lighting. An atmosphere. After such a bad night I must have looked jaundiced, a proper fright, but his eyes were saying no such thing. I lowered my gaze, too.

‘You don’t even know my name.’

‘Care to rectify that?’

‘Darling.’

Delight, disbelief, then that dink of dropping copper. Every time.

‘You’re called Darling?’

Genuine pleasure, as if I’d chosen my ostrich feather of a name just to tickle him under the chin.

‘That’s me.’

‘I’m Thomas,’ he said and I knew, before he had even unlocked his phone, that my digits would soon be safe inside, if …

I ran the test.

‘Go ahead, you can laugh, my Stevie’s friends find my name hilarious too. He’s five; my little terror.’

‘Bet he is,’ he looked down for a moment. Two.

I counted in my head. Six, and then he said:

‘We could meet up sometime. Do you know Andante? The café on Stewart Street?’

I did. ‘I’ll find it.’

‘Could I take your number please, Darling?’

We met at Andante on the Tuesday; a safe get-together over coffee. We knocked around a little conversation like beginners playing pool. I did not smoke. Small sips, no clattering spoons. Then, someone else’s boldness breaking through: honeyed nibbles, unasked-for struffoli doughnuts which the owner brought to our table, flushed and apologising for the interruption, telling us that they meant all our Christmases had come that very morning. It was impossible not to give sweeter, more rounded smiles after that. Fortified, we ventured opening gambits, a brisk mapping out of our positions. I told him I was a trained nurse, and lived alone with Stevie; he was an architect, father to sixteen-year-old Lola and the widower of one Tess. The next time, Friday cinema, brought kisses that were warm if prosaic. I believe we wondered if it could be enough. Did we still carry the seeds for so much possibility? We were hardly teens, after all.

We went back to Andante twice the next week. He dropped in on the way back from the office; the first time I left Stevie with Ange, and then the next time with Demarcus, his father. Thomas revealed that this café had become his preferred thinking space in recent years, somewhere to be when Lola was out and he did not want to sit at home alone. In the battered leather and wood landscape we pitched our hopes on common ground. We drip-dropped our thoughts, tongue-felt the body of the house blend. Short, untroubled dates, tuned and timed so I could leave with a little regret, not too much, go home to breathe in secret smoke and marvel.

The second evening at Andante, a confession:

‘I never loved my wife enough.’

After that, a kiss that mattered. A little too much. Slow and familiar, rude and strong, not so dull as to be perfect; a real headfuck of a sensation, a first. It lifted us. We opened ourselves up to the times that might come after that moment; to possibility.

We stayed up.

Later, in the smallest hours, I dropped the DMD bomb.

‘Stevie has this … He’s been diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.’

‘God, what?’

Guilt. Always that pressed-down guilt at tagging the disease on to my son’s little life like some fucked-up medical degree: Stevie White, DMD. But that’s just how it was: one day you were considering the diagnosis and – pow! – your Wonderboy’s future was punched into the ether.

‘Yes. Sorry, this is hard.’

‘Take your time.’

I hesitated. I would indeed take time to explain everything to Thomas: DMD takes time.

‘DMD is a muscle-wasting disorder, a serious one, that mostly affects boys. It’s progressive. The weakness in the thighs starts at around age five. It makes walking more difficult and climbing the stairs, balancing … and obviously running …’

‘Poor kid.’

‘His callipers, or KAFOs – knee-ankle-foot orthoses – make life easier, although Stevie has better balance than most. Terrible rhythm though …’

(Badaboom! Nerve-soothing black joke for new boo.) I raised my sights, determined not to falter before I had picked off the devastating facts.

‘It is not curable—’

‘Really? God, but—’

‘No. It takes and takes until you have to think about things like sitting, ventilation, fractures and swallowing.’

‘No.’

‘It is rare. Affects 1 in 3,500 males and … the average life expectancy of DMD boys is twenty-seven years.’

‘Shit.’

Yes, Duchenne takes time; all of it, in the end. But that was why Stevie would hear over and over that he was my boy, my lovely little one. As long as he stayed my baby, he would be safe.

‘So you see, Thomas,’ I said. ‘Every moment counts.’

‘I do see. Oh. Darling.’

And just like that, I was not alone.

Entangling my limbs with his, I brightened the tone:

‘It’s fine. Stevie and I talk about it, you know? We even laugh, get silly about it. He doesn’t need to know it all. I tell him, “I will look after you always, sweetness. No need to worry, ever.”’

‘That’s good. And his splints, his callipers, does he have to …’

‘His “superlegs”, you mean? Yes, he wears his KAFOS all day long to help him, but none of that is a problem, I take care of it all.’

‘You’re a great mum.’

‘We’ve had some fantastic support, too. These girls, they call themselves Stevie’s Wonders and they’re a miracle, really. About eight months ago, I told this new nurse, Paula, about Stevie’s diagnosis and next thing all her young student mates started fundraising for him. They’ve raised over £12,000 so far. Amazing, isn’t it?’

I went on to tell him how my son had tried a ‘Wonderburger’ at the launch barbecue – cheese and double bacon! – how I had a framed photo of him with smears of it all over his smiley chin. How the girls had got serious about that smiley chin and next thing done a sponsored bike ride; how boyfriends had joined in with some extreme ironing stunt up a big hill; how a newsletter had emerged. Soon to come was a marathon walk, maybe something in the High Desford Gazette. It was without a doubt the most wonderful miracle.

‘They sound ace,’ said Thomas.

‘Yes, they are, totally. But’ – I eased up on an elbow – ‘I have never wanted Stevie’s needs to be anyone else’s problem. Do you get me? He’s my responsibility.’

Thomas raised himself up to meet my eye. ‘I get you. But help – support – is always better. Right?’

I kissed him in place of a reply. Stevie had always been my responsibility. I was still the one who needed to make everything all right for him. Our generous, warm, bacon-fat days together were destined to be short. Moreover, Duchenne’s was carried in a female carrier but overwhelmingly it affected the male offspring. Passed on, from the mother to the son. I was responsible, in the eyes of those who judged such things. All my fault. I was his cherisher, I had to be, whatever might happen, whatever had happened.

‘He’s a good boy, my baby. You’ll like him.’

‘Of course,’ said Thomas. ‘He does sound wonderful. You’re … Come here.’

After that night, I slapped on nicotine patches and chewed punitive mints after meals. By our third Friday we were doing dinner at the proper-bonkers Lunar (my next test for him: they name tapas-sized Portuguese dishes after dwarf planets and the décor is holiday-misadventures-on-acid, but the guy can cook). He saw past all the crazy-name petiscos, straight to me. And me? I could barely see past the mental fug of non-smoking and the heat-haze from Pluto’s pataniscas de bacalhau, or think past our awed mouths, or get past this interior tightening, this fresh hot-blooded ache …

My phone rang during pudding.

I saw the caller’s name. It took everything not to turn it off altogether – my fingers strained but I simply passed the water jug. Had to let it ring: Stevie was with Ange and my mobile was our mum-hotline. The ringing stopped.

‘What’s wrong?’ Thomas reached for my restless hand.

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘Thought stupid PPI was dead already.’

I turned the ringtone down as low as it would go and raised a pastel de nata to his lips.

On our next date, I would take care of dinner.

The first time you cook for a man is important. It doesn’t just tell him about your tastes, it tells him what you think his tastes are. I had weighed and measured Thomas, more than he would ever know. And so I would cook for him, but not nursery food, no shepherd’s pie cuisine; I was nobody’s bloody nanny. It was summer, but I would not do him the usual platter of cracked shell and bivalve and sea juice. Despite the ordered hair, any fool could see that he was a man who might be persuaded to crunch, suck and snap a bone, when no one else was looking. Meat then, the best, rare sirloin. A bastardised tagliata. A well-hung porterhouse – charred, smeared in garlic, olive oil, lemon and Parmesan, on a bed of rosemary and rocket. Europe slain, seared and bloody on its greenery, there all for him on a plate.

‘I’m going to cook you something,’ I said. ‘Something simple, but a bit different.’

‘Oh good! I’ve always wanted to try real home-cooked Caribbean food.’

‘But, actually I—’

‘I mean, I’ve had a bit of jerk chicken once or twice at a barbecue, but that was just … they were from Devon.’

‘Uh-huh,’ I said.

Mean. It would have been mean, self-defeating and, as the kids had it, ‘awkward’, to say anything more than:

‘Uh-huh, I’m going to cook you up a real Jamaican treat.’

‘Great. What, might I ask?’

So, of course, I had to say:

‘Well, wait and see. But it will be wonky and homemade. It may be naked. Or saucy.’

My mother had fed us well; we ate it all up, with thankful mouths and hands ready to do the dishes. She had grown up in the hills near Negril, where food had winked and dangled from every last tree and nigh on every day had ended in satiety, but for us she worked hard at all those meals that aspired to Englishness, the cabbage-and-potato dinners you could make from ingredients bought from up the road, boiled hard. Just like her cousin, Ionie, who had come over a few years before; just like any other 1970s housewife round their way. One generation on, I stirred up flavours from our blended world in a reduced-to-clear cast aluminium pot from a department store off the M40; a Dutchie by any other name.

She had never sat me down and told me a recipe from back Home – I doubted she even thought of such recipes as formalised processes, never mind written-down documents – and I am sure I never asked. Although a certain amount of osmosis had let the right knowledge flow from her generation to my own, I did not wear the wisdoms of ‘our’ food around me in the way she did, easy as a shawl on a cool Home Counties evening.

And so, two nights before I first cooked for Thomas, I ordered a small cookbook, Jamaican Home Cooking Secrets, for next-day delivery. When the driver, a young West African guy, rocked up with my parcel, my eyes dropped to his trainers, though he had no obvious ability to see my shame through cardboard. I don’t know why I felt so bad; I was born in Basingstoke.

I read, and chilled. Nothing tricky or unfamiliar here; not a single ‘Secret’ worth the name. Just enough prompts to turn the pages of memory: my mother’s island childhood at the kitchen ‘fire’, written down and bound. A right result.

The simplicity itself made me a touch cocky. For my dearest English Thomas, I might start slow: Brown Stew Chicken. I would perform the optional washing of the supermarket chicken with lime even though there was no need: no germs, no heat, and competent fridges. But some traditions existed for good reason; the lime also sharpened the dish. Still, only two-thirds of the Scotch bonnet, without seeds, for my man. The stew would get hotter each time until he became accustomed to ‘our’ levels. I was sure he would like all the teasing, the special treatment.

I tasted the stew.

As sauce hit tongue my mind was shaken by something more surprising than savoury, a memory so strong that it might have come from behind me, or just beyond the door.

I lifted the spoon and turned it in my hand, a dripping totem.

Wah yuh ah duh? Mo salt, yuh si mi?

I turned to face the empty kitchen, then back to my chopping board. I choked on a laugh, silent but fierce, almost a shudder. The black tear fell into the stew.

Dat better, gyal.

The chilli caught the back of my throat.

‘OK,’ I coughed. ‘I hear you.’

A quarter-pinch of allspice and the flavours dropped, settled. This was the right stuff for Thomas. This food sang of bright afternoons to be devoured before they darkened, of passion plated high, of a belief that hungers had to be sated. These dishes stirred you right back.

Not enough though, yet.

I had never once bought callaloo; spinach or kale were more readily available in High Desford. However, I had tracked down a supplier in Brockton – forty-minute drive, plus a full five minutes of speed bumps, mind you – where I bought an astonished boxful of the leafy veg, common to even the most spit-poor yards in Jamaica. Including the petrol, it cost more than Stevie’s shoes. But that green haul of social climbers deserved a Thomas to appreciate them. At the same time, I did wonder whether preparing this authentic Jamaican meal for him was in itself inauthentic, from a woman mostly reared on plain grey mince and plastic butterscotch desserts, just like him. Still, I knew it was a dinner that told more truth about me than lies. Each mouthful would seduce. A sweet smack of plantain and it was done: our hot lovers’ spread.

Thomas, as it happened, would never forget it. Nor would I.

Halfway through, the door went bamm-bam-bam. I knew it was Demarcus, still too much man for doorbells. Thomas shot up, rice falling to the table from his brandished fork.

I opened the door to Demmie, coiled tight as ever and dressed sharp, holding my sleeping son.

‘Y’alright?’ he nodded darkly at Thomas, who sank back down and started piling up my killer crisp-soft plantain on to his plate. ‘Got to go, Darling. I’m going out.’

I kissed Stevie, took him. ‘Where though?’

‘Just out, innit, change of plan. One-off, promise.’

‘Is it a woman?’ I did not smile but I felt no anger either. The spices and simmering had soothed me, and I had missed my baby.

‘What women? Don’t know no women.’

I smiled then, an easy reflex; this was our usual banter, our stock exchange. We were cool with each other, Demarcus and I. He was always a good dad, at least for a dad who couldn’t keep it anything like in his pants. His pants flew off weekly and landed in a different time zone without ever fulfilling their cotton destiny of keeping anything in them. However, when I got pregnant he stuck around, unlike some – unlike many – and we had talked about a flat-pack future, living together, even a wedding at the town hall where his brother could DJ, crack out the old-school ragga. I had been serious and so had he; we were not tripping off down any bumpy babyfather route, I did not want some cartoon of a bruvva cliché. I wanted a real husband, to be a father and son and mum, an all-together family like the one I grew up in.

Our truest story, to be fair: he was no stereotype spat out by potty-mouthed politicians – those whom Mum had christened battymouts – and nor was I. We were just not ready for each other. He liked having a boy but did not rate the stink of nappies. He had liked my milk-heavy breasts but had not wanted to miss Amsterdam to watch me push our son out of that same swollen body. He liked to stroke his son’s cheek goodnight but never woke for him. Or he would already be out. Then my Stevie was diagnosed and Dem, still my anti-husband, would stay out longer, later and longer, until I noticed that I had not seen him for three days and he hadn’t left his best jeans for me to wash and soon he wasn’t even calling me any more to tell me, ‘Don’t know no women.’

Game over, then. But only because I had been ready anyway.

So that night Dem stood there breathing in the peppery tang of another man’s dinner for two and I closed him out with a calm click, and brought Stevie in to meet my new friend, Thomas, and my boy was too drowsy to ask questions, and Thomas was fantastically uncool and kind – with a proper sleep-tight voice, that very first night – and it was enough.

Dem deh two gwan be like bench an’ batty.

As I turned to take Stevie to his bed, my phone went. I stooped to answer it, arms full of son.

‘Oh, I really can’t be arsed to—’

‘Easy, turn it off,’ said Thomas, rising to make us coffee.

I turned it off.

My man, his back to me, waved a silver pouch high. He had sought out some Jamaica Blue Mountain to make for us in my home, perhaps his way of telling me something about how he got me even though he didn’t know me.

Later, in that same kitchen, I was taken aback by just how much he knew me. We went together. He got me.

Stevie was pulling at my hand so hard I nearly sloshed coffee on to the floor.

‘Don’t go out, Mum.’

‘I won’t, poppet, not until much later.’

‘Cuddles!’

‘I’ve told you, darling.’ I bent to hug him. ‘The big lorry was far away, not here.’

He had been clingy ever since that morning, when a new terrorist atrocity had driven a hole through his innocence. He had sensed my alarm at the rolling news. Unable to find the controls I had stared too long, wearing the fear for both of us. My Stevie knew, despite my efforts, and now he did not want me to go out tonight.

‘Are you crying, Mummy?’

‘No, sweetness.’

‘I can stay here, with you. I won’t go to Ange.’

I could not stay. We had awoken to brutality, and to more wrong to come, to every shade of evil directed to extremes. And to change.

But you had to run. Run towards what they hoped you would hate.

‘Ange would miss you too much, my precious. You need to go see her. First though, cornflakes.’

We left the TV off all day and before I could think twice, I was there.

Littleton Lodge, in High Desford Old Town. From my house, it was across the main park and along a bit, on the corner of a lane so green it felt like the gateway to another country. I had walked past it often, this house: set right back, three storeys high and wide, really bloody wide, and white, with wisteria swagged across it. A great fat wodge of Tinkerbell’s wedding cake, it even had the nerve to stand at the end of a muesli-crunch driveway.

Walking up to the house I had noticed a scuff on my black court shoes – bloody gravel – but the door opened before I knocked and – blouse an skirts! Mi neva si huh dere – there she stood, the happy fairy or nymph or sprite, shifting her weight from foot to foot in a pink playsuit. The girl, his girl, with her father coming close up behind her. As I neared them I could see they shared the same welcoming gaze but hers shone from grey, almost metallic eyes, eyes that you knew would not look away first. Her face was warm cream, her shoulders bare, no wings. Lola.

‘Pleased to meet you,’ we said.

I stepped in, Thomas stepped back, there was a hefty ker-chunk of the door and before I had stepped off the doormat Lola had moved forward to wrap me in a surprise: a free and fluid hug. Then she stepped back and smiled up at her father. The dance of greeting, done.

Father and daughter were both barefoot. Burnished floorboards stretched back into hard acres behind them.

The air was so harmonious I was afraid to disturb it:

‘Should I take my shoes off?’

Thomas parted his lips.

‘If you don’t mind, thanks,’ said Lola.

I felt their eyes on me and my marked heels. I should have worn tights: my surprised toenails were unpolished. My toes were silly, stubby and two were considering corns; I had always hated my feet. I was wondering how to work gravel damage and hours spent standing on wards into the conversation as she took my hand and said:

‘Come, I’ll show you around.’

Another easy glance; and yet such ripening wisdom in those silver disc eyes. I put down my handbag. I was dazzled. Truly, I could not take her in.

‘Good girl.’ Thomas was nervous too. ‘I’ll potter off and get on with our dinner. You’re in for a treat! We’re having my special pasta sauce. A real family fave, is it not, Lollapalooza?’

Lola took me from room to room, looking back at me now and then with a certain intensity as if to check that I was missing nothing, noticing it all. How could I not? This was Thomas himself in brick: a home that challenged you not to find it charming and well appointed. It was the generous but cosy, life’s-goshdarn-rosy nest of an architect who had been born with that true American optimism in his blood and still felt he was coming into his greatest powers. As I walked his hallways I believed in him more than ever. Later on he might provoke, or dissemble, or build sustainable grass-roofed mansions, or fool around with the conventions of loft apartment chic, or offer answers to clients’ most difficult prayers in cathedrals of black brick and zinc cladding; later, there was time. For now he lived somewhere that suited him. Clever, with a heart. I was inside what he called his ‘three-dimensional canvas’, in which walls would have been moved, spaces taken up and down and outwards. Lola was formal and proud, but I understood that. I followed her and paused to admire, followed and paused as she padded with unsettling poise – ballet? – around her home. I shuffled through the full tour on my ugly bare feet. We stood caught in our unblinking double glare, the light sting of her scrutinising my back as I wheeled, toes resting to hide for a moment in the pile of a rug, in slow humiliation through the study and the snug, through the whole of her too-lovely world.

Lola beckoned me to the next stop on the tour with a steel-tipped wave. (Her nails and toes were both painted, a shade lighter than her stare.) She was set on showing me all five bedrooms. These would not have been tidied, armfuls stuffed into cupboards, for my eyes only. It was a well-ordered house, grown-up and yet designed to fulfil the grandest hide-and-seek fantasies. By the time we went from her room to the attic (up the secondary doll’s house stairs behind a Narnia door, I kid you not), which they had thought about converting – not her dad, they – I almost wanted to say, ‘OK, I get it and yes, I’m impressed not accustomed, and yes, I’m just the guest …’

But then I thought sixteen and bit my tongue – actually gave myself a salty little nip – and I beamed and nodded, every inch the spellbound stranger, when she asked:

‘So, Darling, would you like to see Dad’s favourite place?’

We traipsed back down the main attic stairs along the landing, and carried on down to the hallway without speaking. A shout from the kitchen over the effortful jazz:

‘All OK, girls?’

‘Fine, Dad!’

Lola and I kept going, to the right, to the left, to the side, through a door hewn out of the fucking Faraway Tree and into the dust of a red-brick landing. Another smaller door. I hesitated:

‘Basement?’

‘Cellar.’

She flicked on a sickly light and I squinted, unsure. Before I could think of three good reasons why not, we were going down. I descended into the B-movie, my mind’s camera shaking, her he’s-behind-you blonde hair swishing in too much shadow to be funny. But something about her steady pace told me she was not acting. Lola led me down into the dark must.

‘Watch these steps,’ she said.

‘Will do, thanks.’

I tried not to mind her. Of course she was showing off the house as if it were double-glazed with diamonds. Anyone would be proud with a dad like Thomas Waite.

At the bottom, another switch; more powerful illumination. Racks stood in rows, housing aristocratic boozers asleep under thin blankets of dust. The stone-carved ceiling curved in places and the ends from wine boxes tiled the walls.

‘Ta-da!’

I nodded and smiled, as required.

‘Go ahead and take a look, it goes right back.’

I had never been a huge wine drinker – a vodka, gin or rum girl, me – and could not spot a good year, coo with urbane delight. However, even I could work out, without looking too hard at the labels, that if wine had been left alone for a few decades you had to be confident that some poor grape-trampling sod would have made it worth the wait.

‘Yes, Dad? Coming!’ A yelled reply to a call I could not hear. ‘Back in a sec.’

She skipped upstairs and left me gazing, with the same eyes I had turned on the ‘original’ fireplaces and the ‘spacious’ study, at a bottle of 2012 Côtes du Roussillon Villages Le Clos des Fées. Ah, fée: French for fairy.

Thud-click.

‘Lola?’

Nothing. Nothing except a muffle-thump of bass, some new and energetic tempo. Was that Queen?

‘Lola?’

I moved, with laboured nonchalance, to the foot of the stairs. Slow, slow, feet chilling on dank stone. I stared up: please, not this. Where the oblong of daylight had shown there was now only black.

‘Lola!’

Nothing but the dun-dun-dun high above, through dense, deaf floors – ‘Under Pressure’? Within seconds the room was pressing against my skin. I sank into a crouch. Walls locking down on me, dead air growing sweet in my nostrils, a sharp whiff of red flowers; the lights dimmed and in my ears dun-dun-dun a drum beating, a dangerous vibration, my lungs tight and full because I must have stopped breathing and then I was pounding upwards, upstairs dun-dun-dun-dun pounding hard into hard blackness:

‘Lola!’

I hit at the door dun-dun-dun. Not goddamn ‘I Want to Break Free’, no way. She couldn’t have.

‘Lola! Lola, let me out. Get me out now!’

Too loud, too far. My mobile; it was still in my handbag by the front door, next to my shamed shoes.

‘Lola! Lola!’

I could feel tears bleeding into the sweat at my temples.

Then a blinding of light and air and noise rushed in and she was there, a bending shadow. Oxygen, music washed me down (my hysterical ears now heard ‘Killer Queen’) and Lola swept me up.

‘Oh, you poor thing, I’m so sorry!’

‘I thought—’

‘This stupid beeping door. God, Darling, so sorry. It must have locked behind me, it’s been sticking lately.’

She took my hand and led me through the first door back to safety. Thomas danced out, a seafood cocktail in each hand. Seeing me he stopped dead:

‘What’s wrong, what—?’

‘The cellar door, Dad. Knew it would do that sooner or later.’

‘I’m fine.’ The veil of sweat said more, the tacky film noir on my face. I dropped her hand.

We ate. The prawns were perky, the pasta porky; paccheri topped with a fat chop, rubbed with salt and fresh oregano, in a more than passable passata. But I was done in. I laughed too loud, complimented everything Thomas had created: the dinner, all things Lola. I tried, but the pulsing music was all dun-dun-dun and I could not follow the chatter, my flesh had been rubbed with salt sweat and fear, and my wine tasted sharp, all wrong. We ate on as my toes curled up on themselves, defeated. My smiles lied broad and long, as did the yawns at around 9.30 p.m. Enough. Our night had been left behind, locked in the cellar, and I pleaded an early start with Stevie: physio. I would gather up my boy, he could sleep in my bed after all.

I pecked Thomas and hugged Lola, realising as I backed away that I knew little more about her than when she had first landed those eyes on me. As the door closed, those eyes put me in mind of magnesium, with the potential to flare bright. Or perhaps the casings of incendiary devices, of dormant bombs. Yes, that was it. In a certain light, Lola looked like she could go off at any moment.