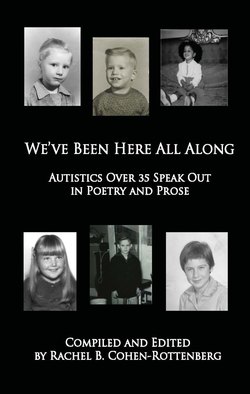

Читать книгу We've Been Here All Along: Autistics Over 35 Speak Out in Poetry and Prose - Rachel Inc. Cohen-Rottenberg - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеClay

Clay has been a sailor who never went to sea, a parts clerk, a truck driver, a service station owner, and a belated college student. He was a “weed-abater” (cutting, stacking, and burning weeds along the All-American Canal), a service station attendant, a “leadman” at a motor home factory, a house painter, a building maintenance worker at a rather exclusive country club, and a salad and sandwich maker at a high-falutin’ restaurant. He has finished pianos and waited counters, spent several years converting an old printing factory into an urban shopping mall, and worked for 16 years as a home health aide. Whatever he did, it was to put the finishing touches on something. He is now retired.

My Love Affair with Words

Kindergarten was a half-day affair. I’d spend the morning watching the brand-new TV my father had gotten us the Christmas before, totally enthralled by such old-time greats as Kate Smith, Johnny Ray, Pinky Lee, and Les Paul and Mary Ford. I know that many people will say that TV is a huge waste of time, the opiate of the masses. To me, it was simply great, because I finally had someone (okay, something) that would talk to me, and I was avidly seeking to increase my vocabulary.

See, I had this love affair with words.

There was this weird thing I would do whenever I heard a word that was new to me. I would withdraw from whatever was happening and repeat it about five or six times. When I was done, I knew what it meant. My sisters used to see me engaging in this ritual, and they commented on it, but I didn’t tell them what I was doing. You might think that I had figured out the meaning by the context in which the word was used. I did, but the process entailed far more than that.

One day, early on in kindergarten, Miss Potts played a game that was designed to teach us to raise our hands to ask or answer questions. She would ask, “What sound does a duck make?” Someone would raise his hand to say, “They say, quack.”

“Very good. Now, what sound does a cow make?”

“They say, moo.”

“All right. Now, what sound does a horse make?”

The other kids didn’t seem to know, but I had learned it from reading Donald Duck comics, so I said, “Horses say, neigh.”

Miss Potts stopped moment, a smile on her face, and replied, “They say nay? Then they should run for Parliament!”

This rejoinder brought a chuckle from the kids and a slow burn to my ears. I was about to say, “N-e-i-g-h! Look it up!” But she had said “Parliament,” and I had to withdraw to process the word. It took only about 10 seconds or less to come up with “form of government in England and its colonies,” but by then, she had gone on to pigs.

Now, I had learned the song The Mademoiselle from Armentieres, Parlez-Vous, so it was not hard to make the connection from “parlez” to “talking establishment,” but I had gone somewhere inside to access the information.

A couple of years later, when I had internalized the rules of English grammar and spelling, I was also able to know the correct spelling of words I had only heard. It wasn’t that I automatically knew how to spell something like “perspicacious.” I couldn’t visualize the word, but I would start writing it and, if I made a mistake, I would recognize it and know how to fix it. I didn’t always win the spelling bees, but I got perfect scores on spelling tests. I also somehow understood the words’ etymologies, whether they had derived from French, Old High German, Old English, Latin, or Greek. I was surprised when I came across the simple word “tattoo.” I got nothing at all, but that was because the word was completely unrelated to any language base with which I was familiar. I also don’t understand the etymology of any technological jargon, or of anything specific to science or math at all.

I never talked with anyone about these skills, but I recall wondering about them while walking to school. I came up with the theory that I must have lived before, probably as an English professor, and had retained the vocabulary. Every time I heard a new word, it was as though a bell had gone off. While processing the word, there was a feeling of becoming reacquainted with an old friend.

My friend Frank didn’t believe me. He called it “magical thinking,” because he couldn’t find an explanation in his strictly logical world. By then, I had realized that it was a savant skill. I know that there is absolutely no way to prove it now, but if this savant skill had been recognized when I five or ten years old, life might have unfolded quite differently.